BRIBERY

Bribery, the purchase of influence or favor from a public official, is a topic of great import to companies that do business outside the United States. While arguably some forms of legalized bribery occur routinely within U.S. borders, notably in the funding of political campaigns. multinational corporations are often faced with more direct and pervasive bribery practices abroad.

Bribing U.S. government officials has always been a crime, but it wasn't until the 1970s that buying influence with foreign governments became illegal for U.S. businesses. Until then, some reports suggest that a quarter of the Fortune 500 companies engaged—legally—in foreign bribery. Indeed, the practice had been commonplace, and remained so through the late 1990s for many companies outside the United States. This occurred to such an extent that U.S. companies tended to be at a disadvantage in foreign markets because they didn't bribe. Although some claim even the U.S. bribery laws are too weak and rife with loopholes, the U.S. antibribery policy is one of the world's toughest and has been a model for other countries.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE U.S. LAW

Several events led to the United States' attempt to quash foreign bribery. In 1976, members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the group of industrialized, market-economy nations (including the United States), signed the Declaration on International Investment and Multinational Enterprises. Part of this nonbinding agreement was a clause that denounced the practices of (I) companies offering bribes to public officials and (2) officials seeking such payments, a form of bribery sometimes known as graft. In 1977, the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), a private business-promotion organization, followed suit and adopted a code of behavior to combat extortion and bribery in business transactions. A group was established to interpret, promote, and apply the code.

Closer to home, the post-Watergate Congress was already receptive to tightening anti-corruption laws. To address the foreign bribery concerns that had been drawing so much international attention, it passed the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) of 1977, an amendment to the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 that defined appropriate ethical and legal behavior. The FCPA, as later amended, remains the core of U.S. foreign bribery law. It contained three main provisions:

- An antibribery section, prohibiting U.S. companies from paying bribes to obtain contracts in foreign countries.

- An accounting/record-keeping section that requires firms to set up internal accounting controls to provide assurance that transactions are executed in accordance with management's general or specific authorization.

- A penalty section that holds business firms liable for a fine of up to $1 million for each violation; individual liability includes fines of up to $10,000 and up to five years in prison. The U.S. Supreme Court subsequently held that violation of the antibribery provisions of the FCPA can result in a private cause of action.

The FCPA outlaws both variance and outright purchase bribes. Variance bribes are payments made to secure a variance from an existing law or regulation—for instance, a payment made to an official to overlook an act that violates local pollution laws. Outright purchase bribes are payments or gifts made to officials to obtain government contracts.

The FCPA has been strengthened by case law so that businesses may sue competitors for lost business if they can prove that bribery played a significant role in decisions made.

While, originally, the FCPA held U.S. companies liable if they knew, or had reason to know, that a payment was made on their behalf to a government official, the Omnibus Trade Act of 1988 modified this so that a company could only be held criminally liable if it could be proven that the company had actual knowledge of an illegal payment. In addition, under the Omnibus Trade Act, some forms of bribery are considered acceptable such as transaction bribes—payments made to speed the completion of a routine, clerical-type function such as the processing of papers or moving goods through customs.

MAJOR BRIBERY CASES

Defense contractor Lockheed Corp. has been implicated in more than one high-profile bribery case. In the 1970s, Lockheed was involved in the payment of an estimated $25 million to Japanese officials to secure the sale of its Tristar L-1011 aircraft. The act resulted in the resignation, and eventual criminal conviction, of Japanese Prime Minister Kukeo Tanaka. Japan was not the only country involved. Lockheed admitted to making payments to secure sales in 15 countries, including the Netherlands, Italy, and Turkey. This case helped spur passage of the FCPA.

A decade later Lockheed was caught in another bribery scandal, this time in Egypt—and this time in violation of U.S. law. In 1987, Lockheed began paying a newly elected member of the Egyptian parliament in order to encourage the government's purchase of its planes. When the company finally admitted to wrongdoing in 1995, it was slapped with $25 million in fines and one company official was imprisoned.

In the late 1980s, Young & Rubicam Inc., an international advertising firm, was indicted under the FCPA because the company had reason to know that one of its agents in Jamaica was paying off the minister of tourism to obtain advertising business. The case was settled when the company paid a penalty of $500,000 to avoid further litigation.

RECENT TRENDS

While the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act has made such cases relatively rare in the United States, for many companies based in other parts of the world, including foreign-based subsidiaries of U.S. companies, bribery remains the rule rather than the exception. Within certain European nations, for instance, not only has foreign bribery been permissible, but companies have also been able to take tax deductions for the bribes they pay, as they would for any other qualifying business expense.

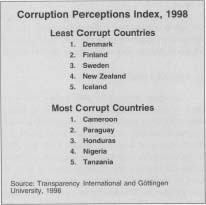

A Berlin, Germany-based anti-corruption group called Transparency International attempts to measure the relative corruption of various countries. Its widely cited annual Corruption Perceptions Index ranks countries based on how a sample of business people perceive corruption in those places. The table below shows which nations rank at the top and bottom of the 1998 index. The United States placed at No. 17 of the 85 countries monitored.

Least Corrupt Countries

|

Most Corrupt Countries

|

The U.S. Department of Commerce estimated that U.S. companies lose billions of dollars each year in potential foreign business when they lose out to competitors that bribe. These practices also hamper the development of international trade by restricting free and open markets, destroying competition, and increasing the cost of doing business. Perhaps not surprisingly, economists have also linked bribery to inefficiency and poor economic performance. To level the playing field, corporate America has actively promoted antibribery initiatives on the world stage.

However, critics suggest that U.S. attempts to advance antibribery statutes are disingenuous. A conspicuous example unfolded in Argentina. According to confessions from officials at the Argentine Banco de la Nacion, a government institution, International Business Machines Corporation paid them tens of millions of dollars in order to win the bank's lucrative $250 million service contract (it later lost the contract when the scandal was uncovered). Such a bribe was illegal under the laws of both Argentina and the United States. But after U.S.-based IBM executives were named as decision-makers in the scandal, the U.S. government found itself in the awkward position of defending the executives' right to escape prosecution in Argentina, where a judge had demanded their arrest, while U.S. diplomats were singling out Argentina as a country that needed to promote transparency and combat corruption in its legal system. This seemingly contradictory stance drew sharp criticism from Argentine authorities, who claimed the United States maintained a double standard.

Nonetheless, in the late 1990s there was a decided trend against bribery in international business. On a practical note, the scale of bribes in some places had swelled to such a hefty proportion of the contract under consideration that bribery was much less cost effective than before. From just 5 percent of a contract in the olden days, bribe-takers now frequently expected to land upwards of 20 percent of a contract's value for their services. Anecdotally, there was some evidence that in some countries public sentiment turned against bribery and related practices.

As a result, after two decades of stalling since the original OECD declaration, a major antibribery treaty, the Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions, was signed in 1997. The participants included all of the 29 OECD countries as well as Argentina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Chile, and Slovakia. The treaty, which took effect in February 1999, required members to create laws that criminalize bribery of foreign officials, similar to the U.S. model, if such laws weren't already in effect. China was the only major U.S. trading partner that hadn't signed the convention.

FURTHER READING:

Andelman, David A. "Bribery: The New Global Outlaw." Management Review, I April 1998.

Celarier, Michelle. "The Road to Excess." CFO, November 1998.

"A Global War Against Bribery." Economist, 16 January 1999.

Ivanovich, David. "More Nations Join U.S. Fight against Bribery." Houston Chronicle, 29 October 1998.

Transparency International. "The Corruption Perceptions Index." Berlin, Germany, 1998. Available from www.transparency.de .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: