BUDGETING

Since companies strive for profitability through the efficient and economical use of resources and labor, they require financial road maps to show how they will allocate their resources to achieve their business objectives. In other words, companies require prudent budgeting to accomplish their goals. Companies practice budgeting—the estimation of probable expenditures and income for a specific period—to determine the most efficient and effective strategies for making money and expanding their assets. Budgeting allows companies to control their expenditures and to allocate resources to maximize profits, thus allowing them to demonstrate to banks, investors, and shareholders that they have a plan for where they are going.

Intelligent budgeting incorporates good business judgment in the review and analysis of past trends and data pertinent to the business enterprise. This information assists a company in determining the type of business organization needed, the amount of money to be invested, the type and number of employees to hire, and the marketing strategies required. In budgeting, a company devises both long-term and short-term plans to help implement its strategies and to conduct ongoing performance evaluations.

Businesses generally develop and execute their budgeting plans each year, in a five-step process called the planning cycle. First, companies develop a strategic plan that focuses on their long-term goals and how to achieve them. The strategic plan typically includes general financial projections and covers a five-year period. Second, businesses prepare an annual operating plan that provides a detailed outlook for the coming year. This plan contains very specific financial projections and often is what companies refer to by "budget." Third, since things change after the year actually starts, businesses revise their plans, yielding their adjusted plan. The adjusted plan takes sudden and unforeseen changes into consideration. Fourth, companies often make forecasts, or informal projections, throughout the year. For example, businesses frequently predict their annual sales at mid-year. Fifth, companies produce their business plans, which they use to apply for venture capital and other investments. The business plans also often contain detailed financial projections.

A host of management personnel participates in the budgeting process. In general these participants include "submitters" and "reviewers." The submitters are usually division managers who prepare and propose possible spending plans to achieve company goals, whereas the reviewers are often executives, controllers, or accountants who determine whether the proposed budgets and their objectives are affordable, realistic, and attainable. These roles, however, are not mutually exclusive: those who submit budget proposals often review other proposals and vice versa.

A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

The practice of budgeting has existed for ages. In ancient times individuals and societies engaged in processes of planning their economic activities, evaluating the annual outcomes, and revising when necessary. Through observation and experimentation, agrarian peoples discovered, invented, and standardized various practices to increase the quality and quantity of their yields.

The desire for excess supplies to sell for profits, and for storage as wealth, led people to make plans to maximize their income by budgeting a certain amount of money and energy for stabilizing farming conditions. These efforts brought about the discovery and use of crop rotation, fertilizers, fences, scarecrows, and irrigation. While having few devices against the vagaries of the weather, ancient peoples used their profits and hard labor to protect their fields by deploying armies, building walls, planting in remote locations, and paying tribute to powerful neighbors. Similarly, modern peoples employ various strategies to use their accumulated wealth to generate new profits and to continually expand their wealth. The fact that modem budgeting generally consists of a series of 12-month periods may reflect these agrarian origins.

PLANNING FOR PROFIT

To engage in any profitable commercial enterprise, a company employs its resources to exploit various business opportunities. If the profits are consistent, a company may purchase more assets and, therefore, expand its base of wealth. To do this effectively, a company undertakes the budgeting process to assess the business opportunities available to it, the keys to successfully exploiting these opportunities, the strategies the historical data support as most likely to succeed, and the goals and objectives the company must establish. Companies also must plan long term strategies that define the overall plan to build market share, increase revenues, and decrease costs. In addition, companies require short-term strategies to increase profits, control costs, and invest for the future. Both long-term and short-term strategies must contain control mechanisms for implementing performance evaluations as well as control mechanisms for making modifications in the above strategies when and where necessary.

Although company leaders generally conceive of business opportunities and initially provide the impetus to pursue them, companies move beyond the embryonic stage by formulating their strategies in quantifiable terms, such as: the volume of units that the company expects it can sell, the percentage of market share the volume of units represents, the dollars of revenues it will receive from these sales, and the dollars of profit it will earn. Likewise, a company outlines its long-term goals and specifies its short-range plans in quantifiable terms that detail how it expects to accomplish its goals:

- the dollars the company will spend in selling the units

- the dollar costs of producing the units

- the dollar costs of administering the company's operations

- the dollars the company will invest in expanding and upgrading facilities and equipment

- the flow of dollars into the company coffers

- the financial position, expressed in dollars, at specific points in the future

To be successful, the budgeting process establishes criteria and control mechanisms for the systematic evaluation of the company's ability to effectively implement its plans. These controls are often detailed and complex. Therefore, the company includes in the budgeting process employees from each organizational level and from each department. The company marshals these resources in a coordinated effort in the following functions.

PLANNING.

The company establishes long-term financial goals and operational objectives for the future size and activities of the company. These include products, product mix, services, markets, market share, volume of sales, quality of sales, level of debt and capitalization, number of employees, degree of horizontal and vertical integration, research and development , public or private ownership, advertising campaigns, training and development, and benefit packages.

STAFFING.

The company clearly defines and assigns responsibility for the budgeting process itself, along with the level of detail required to formulate the business plan. The treasurer's office generally organizes and coordinates the budgetary process through a budget director, controller, or chief accountant. Budgeting hinges on accurate accounting of all activities, including machine use, manpower needs, employee turnover, inventory levels, supplier pricing, sales discounts, benefit costs, production schedules, selling costs, and the like. Therefore, the accounting staff plays a central role in collecting, analyzing, and processing the needed data. Contemporary approaches to budgeting, however, often emphasize the role of managers in the budgeting process.

ORGANIZING.

In planning for profits the staff needs to organize for action. They provide standardized reporting directives. The staff distributes familiar and "user-friendly" forms for collecting, organizing, evaluating, and disseminating information. They propose procedures to form a comprehensive plan for each activity and for the company as a whole.

DIRECTING.

The budgetary process establishes lines of reporting and accountability for the execution of the plan. Besides spelling out the various responsibilities of the managers, it also places limits on their authority. The budgeting process involves all levels of managerial responsibility: office, department, division, and corporation. To maximize the benefits of the budgeting process, managers must not only be responsible and accountable, but also need to be in agreement with overall goals and objectives.

CONTROLLING.

The budgetary process sets up the reporting procedures and techniques for evaluating both short-term and long-term outcomes. Since the budget program is an instrument of organizational control, a company's accounting and its chart of accounts will reflect clear lines of responsibility for each of its divisions. Not all control activity, however, emanates from the accounting office. Line supervisors and individual employees keep their own logs. Consequently, the accounting/budgeting staff sets up schedules for the collection, processing, and analysis of data and its subsequent distribution to the appropriate managers. The managers use this information to evaluate their own performance with an eye toward making modifications where necessary.

THE FINANCIAL FORECAST AND THE

BUDGET

The end product of this process is the creation of the financial forecast. It projects where the company wants to be in three, five, or ten years. The financial forecast quantifies future sales, expenses, and earnings according to certain assumptions adopted by the company. Since projecting company sales, expenditures, etc., involves uncertainty, a company must consider how changes in the business climate could affect the outcomes projected. A company presents this analysis in the pro forma statement, which displays, over a time continuum, a comparison of the financial plan to "best case" and "worst case" scenarios. The pro forma statement acts as a guide for meeting goals and objectives, as well as an evaluative tool for assessing progress and profitability.

Through forecasting a company attempts to determine whether and to what degree its long-range plans are feasible. This discipline incorporates two interrelated functions: long-term planning based on realistic goals and objectives and a prognosis of the various conditions that possibly will affect these goals and objectives; and short-term planning and budgeting that provide details about the distribution of income and expenses and a control mechanism for evaluating performance. Forecasting is a process for maximizing the profitable use of business assets in relation to: the analyses of all the latest relevant information by tested and logically sound statistical and econometric techniques; the interpretation and application of these analyses into future scenarios; and the calculation of reasonable probabilities based on sound business judgment.

Future projections for extended periods, although necessary and prudent, suffer from a multitude of unknowns: inflation, supply fluctuations, demand variations, credit shortages, employee qualifications, regulatory changes, management turnover, and the like. If a budget fails to distinguish between what management can and cannot control, it also will fail to indicate whether management is successful or unsuccessful, or merely fortunate or unfortunate. To increase control over operations, a company narrows its focus to forecasting attainable results over the short term and identify the assumptions it makes concerning the uncertainties. These short-term forecasts, called budgets, are formal, comprehensive plans, using quantitative terms to describe the expected operations of the organization over some specified future period. While a company may make few modifications to its forecast, for instance, in the first three years, the company constructs individual budgets for each year. Furthermore, this approach allows a company to periodically review the assumptions it makes and revise them if necessary.

A budget delineates the expected month-to-month route a company will take in achieving its goals. It summarizes the expected outcomes of production and marketing efforts, and provides management benchmarks against which to compare actual outcomes. A budget acts as a control mechanism by pointing out soft spots in the planning process or in the execution of the plans. Consequently, a budget, used as an evaluative tool, augments a company's ability to make necessary alterations more quickly.

PRINCIPLES AND PROCEDURES FOR

SUCCESSFUL BUDGETING

REALISTIC AND QUANTIFIABLE GOALS.

In a world of limited resources, a company must ration its own resources by setting goals that are reasonably attainable. Realism engenders loyalty and commitment among employees, motivating them to their highest performance. In addition, wide discrepancies, caused by unrealistic projections, have a negative effect on the creditworthiness of a company and may dissuade lenders.

A company evaluates each potential business activity to determine which will help the company achieve its goals the most. A company accomplishes this through the quantification of the costs and benefits of the activities.

HISTORICAL COMPONENT.

The budget reflects a clear understanding of past results and a keen sense of expected future changes. While past results cannot be a perfect predictor, they flag important events and benchmarks.

PERIOD-SPECIFIC BUDGETING.

The budget period must be of reasonable length. The shorter the period, the greater the need for detail and control mechanisms. The length of the budget period dictates the time limitations for introducing effective modifications. Although plans and projects differ in length and scope, a company formulates each of its budgets on a 12-month basis.

STANDARDIZATION.

To facilitate the budgeting process, managers should use standardized forms, formulas, and research techniques. This increases the efficiency and consistency of the input and the quality of the planning. Computer aided accounting, analyzing, and reporting not only furnish managers with comprehensive, current "real time" results, but also afford them the flexibility to test new models, and to include relevant and high-powered charts and tables with relatively little effort.

INCLUSIVE PROCESS.

Efficient companies decentralize the budget process down to the smallest, logical level of responsibility, i.e., the responsibility center. Responsibility centers often include the revenue center, the cost center, and the profit center. Those responsible for the results take part in the development of their budgets, and learn how their activities are interrelated with the other segments of the company. Each has a hand in creating a budget and setting its goals. Participants from the various organizational segments meet to exchange ideas and objectives, to discover new ideas, and to minimize redundancies and counterproductive programs. This way, those accountable buy into the process, cooperate more, work harder, and, therefore, have more potential for success.

BUDGET REVIEW.

Decentralization does not exclude the thorough review of budget proposals at successive management levels. Management review assures a proper fit within the overall "master budget."

ADOPTION AND DISSEMINATION.

Top management formally adopts the budgets and communicates their decisions to the responsible personnel. When top management has assembled the master budget and formally accepted it as the operating plan for the company, it distributes it in a timely manner.

FREQUENT EVALUATION.

Responsible parties use the master budget and their responsibility center budgets for information and guidance. On a regular basis, according to a schedule and in a standardized manner, they compare actual results with their budgets. For an annual budget, managers usually report monthly, quarterly, and semiannually. Since considerable detail is needed, the accountant plays a vital role in the reporting function.

A company uses a well-designed budget program as an effective mechanism for forecasting realizable results over a specific period, planning and coordinating its various operations, and controlling the implementation of the budget plans.

FUNCTIONS AND BENEFITS OF THE

BUDGETING PROGRAM

Budgeting has two primary functions: planning and control. The planning process expresses all the ideas and plans in quantifiable terms. Careful planning in the initial stages creates the framework for control, which a company initiates when it includes each responsibility center in the budgeting process, standardizes procedures, defines lines of responsibility, establishes performance criteria, and sets up timetables.

The careful planning and control of a budget benefit a company in many ways, including:

ENHANCING MANAGERIAL PERSPECTIVE.

In recent years the pace and complexity of business have out-paced the ability to manage by "the seat of your pants." On a day-to day basis, most managers focus their attention on routine problems. In preparing the budget, however, managers are compelled to consider all aspects of a company's internal activities. The act of making estimates about future economic conditions and about the company's ability to respond to them, forces managers to synthesize the external economic environment with their internal objectives.

FLAGGING POTENTIAL PROBLEMS.

Because the budget is a blueprint and road map, it alerts managers to variations from expectations that are a cause for concern. When a flag is raised, managers can revise their immediate plans to change a product mix, revamp an advertising campaign, or borrow money to cover cash shortfalls.

COORDINATING ACTIVITIES.

Preparation of a budget assumes the inclusion and coordination of the activities of the various segments within a business. The budgeting process demonstrates to managers the interconnectedness of their activities.

EVALUATING PERFORMANCE.

Budgets provide management with established criteria for quick and easy performance evaluations. Managers may increase activities in one area where results are well beyond exceptions. In other instances, managers may need to reorganize activities whose outcomes demonstrate a consistent pattern of inefficiency.

REFINING THE HISTORICAL VIEW.

The importance of clear and detailed historical data cannot be overstated. Yet, the budgeting process cannot allow the historical perspective to become crystallized. Managers need to distill the lessons of the most current results and filter them through their historical perspective. The need for a flexible and relevant historical perspective warrants its vigilant revision and expansion as conditions and experience warrant.

THE MASTER BUDGET: A PROFIT PLAN

The master budget aggregates all business activities into one comprehensive plan. It is not a single document, but the compilation of many interrelated budgets that together outline an organization's business activities for the coming year. To achieve the maximum results, budgets must be tailor-made to fit the particular needs of a business. Standardization of the process facilitates comparison and aggregation even of mixed industries, for example, financial services (General Motors Credit Corp.) and manufacturing (General Motors Corp.).

In the following discussion the term "production" includes the manufacture of goods expressed by their dollar value and number of units, and the provision of services expressed in labor-hours and in dollar value.

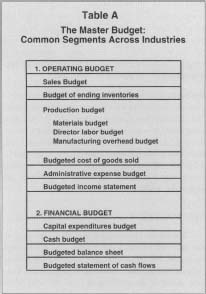

Table A presents an overview of the master budget. The budgeting process is sequential in nature, i.e., each budget hinges on a previous budget, such that no budget can be constructed without the data from the preceding budget. In addition, each line budget is comprised of a number of smaller responsibility center budgets. Responsibility budgets are an important element of an effective accounting system.

CLASSIFICATIONS AND TYPES OF

BUDGETS

Budgets may be broadly classified according to how a company makes and uses its money. Different budgets may be used for different applications. Some budgets deal with sources of income from sales, interest, dividend income, and other sources. Others detail the sources of expenditures such as labor, materials, interest payments, taxes, and insurance. Additional types of budgets are concerned with investing funds for capital expenditures such as plant and equipment;

The Master Budget:

Common Segments Across Industries

| 1. OPERATING BUDGET |

| Sales Budget |

| Budget of ending inventories |

|

Production budget

Materials budget Director labor budget Manufacturing overhead budget |

| Budgeted cost of goods sold |

| Administrative expense budget |

| Budgeted income statement |

| 2. FINANCIAL BUDGET |

| Capital expenditures budget |

| Cash budget |

| Budgeted balance sheet |

| Budgeted statement of cash flows |

and some budgets predict the amounts of funds a company will have at the end of a period.

A company cannot use only one type of budget to accommodate all its operations. Therefore, it chooses from among the following budget types.

The fixed budget, often called a static budget, is not subject to change or alteration during the budget period. A company "fixes" budgets in at least two circumstances.

- The cost of a budgeted activity shows little or no change when the volume of production fluctuates within an expected range of values. For example, a 10 percent increase in production has little or no impact on administrative expenses.

- The volume of production remains steady or follows a tight, preset schedule during the budget period. A company may fix its production volume in response to an all-inclusive contract or it may produce stock goods.

The variable or flexible budget is also called a dynamic budget. It is an effective evaluative tool for a company that frequently experiences variations in sales volume that strongly affect the level of production. In these circumstances a company initially constructs a series of budgets for a range of production volumes that it can reasonably and profitably meet.

After careful analysis of each element of the production process, managers are able to determine the fixed costs (e.g., taxes) that will not change within the anticipated range, the variable costs (e.g., raw materials) that will change as volume changes, and the semivariable costs (e.g., equipment maintenance fees) that vary to some extent, but not proportionately within the predicted range.

The combination budget recognizes that most production activities combine both fixed and variable budgets within its master budget. For example, an increase in the volume of sales may have no impact on sales expenses while it will increase production costs.

The continuous budget adds a new period (month) to the budget as the current period comes to a close. Under the fiscal year approach, the budget year becomes shorter as the year progresses. The continuous method, however, forces managers to review and assess the budget estimates for a never-ending 12-month cycle.

THE BUDGET PERIOD

As a general rule, a company adopts budgets covering a period long enough to show the effects of managerial policies, but short enough so as to make estimates with reasonable accuracy. Although planned activities differ in the length of operation, budgets describe only what a company expects to accomplish in the upcoming 12 months.

Capital expenditures for major investments in plant and equipment are long term by nature. A company constructing new facilities, laying pipelines, or paving roads may design projects encompassing periods of five to ten years. Nevertheless, a company details the ongoing expenses on an annual basis.

Most operating and financial budgets (Table A) cover a period of one fiscal year, comprised of 12 months arranged in quarters (segments of three months) and semiannual periods (segments of six months).

THE OPERATING BUDGET

The operating budget gathers the projected results of the operating decisions made by a company to exploit available business opportunities. In the end analysis, the operating budget presents a projected pro forma income statement that displays how much money the company expects to make. This net income demonstrates the degree to which management is able to respond to the market in supplying the right product at an attractive price, with a profit to the company.

The operating budget consists of a number of parts that detail the company's plans on how to capture revenues, provide adequate supply, control costs, and organize the labor force. These parts are: sales budget, production budget, direct materials budget, direct labor budget, factory overhead budget, selling and administrative expense budget, and pro forma income statement.

PREPARATION OF THE MASTER BUDGET

Preparation of the master budget is a sequential process that starts with the sales budget. The sales budget predicts the number of units a company expects to sell. From this information, a company determines how many units it must produce. Subsequently, it calculates how much it will spend to produce the required number of units. Finally, it uses all this information to estimate its profitability.

From the level of projected profits, the company decides whether to reinvest the funds in the business or in alternative investments. The company outlines the predicted results of its plans in a balance sheet that demonstrates how profits will have affected the company's assets.

Accounting: The Basis for Business Decisions notes the five major, sequential steps to preparing a master budget:

- Preparation of the sales forecast. How many units can be sold? How many units will be sold? How much will it cost to sell these units? How much net revenue will these sales generate?

- Preparation of the production and operating costs. How much will it cost to produce the units? How can production be more efficient? How much will administrative expenses run?

- Preparation of a budgeted income statement. What will be the net income? How much will be cash, credit, and noncollectible? How much will be available for capital investments? How much will remain as cash for financing daily operations?

- Preparation of a cash budget. Will cash flow be adequate? Will receipts be evenly or erratically distributed? Will third-party financing be needed? How are excess funds to be invested? How much of the funds will be needed for capital expenditures?

- Preparation of a budgeted balance sheet. How will the period's performance change the level of assets and liabilities? How will the profit position of the company change? How will the company's wealth be affected?

THE SALES FORECAST AND BUDGET

The sales organization has the primary responsibility of preparing the sales forecast. Since the sales forecast is the starting point in constructing the sales budget, the input and involvement of most other managers is important. First, those responsible for directing the overall effort of budgeting and planning contribute leadership, coordination, and legitimacy to the resulting forecast. Second, in order to introduce new products or to repackage existing lines, the sales managers need to elicit the cooperation of the production and the design departments. Finally, the sales team must get the support of the top executives for their plan.

The sales forecast is prerequisite to devising the sales budget on which a company can reasonably schedule production, and to budgeting revenues and variable costs. The sales budget, also called the revenue budget, is the preliminary step in preparing the master budget. After a company has estimated the range of sales it may experience, it calculates projected revenues by multiplying the number of units by their sales price.

The sales budget includes items such as: sales expressed in both the number of units and the dollars of revenue, adjustments to sales revenues for allowances made and goods returned, salaries and benefits of the sales force, delivery and setup costs, supplies and other expenses supporting sales, advertising costs, and the distribution of receipt of payments for goods sold. Included in the sales budget is a projection of the distribution of payments for goods sold. Management forecasts the timing of receipts based on a number of considerations: the ability of the sales force to encourage customers to pay on time, the impact of credit sales that stretch the collection period, delays in payment due to deteriorating market and economic conditions, the ability of the company to make deliveries on time, and the quality of the service and technical staffs.

THE ENDING INVENTORY BUDGET

The ending inventory budget presents the dollar value and the number of units a company wishes to have in inventory at the end of the period. From this budget, a company computes its cost of goods sold for the budgeted income statement. It also projects the dollar value of the ending materials and finished-goods inventory, which eventually will appear on the budgeted balance sheet. Since inventories comprise a major portion of current assets, the ending inventory budget is essential for the construction of the budgeted financial statement.

THE PRODUCTION BUDGET

After it budgets sales, a company examines how many units it has on hand and how many it wants at year-end. From this it calculates the number of units needed to be produced during the upcoming period. The company adjusts the level of production to account for the difference between total projected sales and the number of units currently in inventory (the beginning inventory), in the process of being finished (work [goods, services] in process inventory), and finished goods in the ending inventory.

To calculate total production requirements, a company adds projected sales to ending inventory and subtracts the beginning inventory from that sum.

BEGINNING INVENTORY BUDGET

The products completed and available for sale at the start of the period make up the beginning inventory budget. A company determines the value of the beginning inventory by: counting all products on hand, multiplying this quantify by the cost per unit, and aggregating the costs of the various products.

WORK IN PROCESS BUDGET

The work in process budget enumerates those units currently in the production phase. There inevitably will be some work in process at every point in the budget period. Therefore, a company needs to determine the number and value of the beginning and ending work in process inventories. Because the items are in different stages of production and finishing, these computations present a problem. Although computer technology has made great strides in simplifying the accounting process, predictive accuracy is contingent on the experience of line supervisors who feed the data to the accountants.

THE DIRECT-MATERIALS BUDGET

With the estimated level of production in hand, the company constructs a direct-materials budget to determine the amount of additional materials needed to meet the projected production levels. A company displays this information in two tables. The first table presents the number of units to be purchased and the dollar cost for these purchases. The second table is a schedule of the expected cash distributions to suppliers of materials.

Purchases are contingent on the expected usage of materials and current inventory levels. The formula for the calculation for materials purchases is:

Purchase costs are simply calculated:

A company plans a direct-materials budget to determine the adequacy of their storage space, to institute or refine just-in-time inventory control systems, to review the ability of vendors to supply materials in the quantities desired, and to schedule material purchases concomitant with the flow of funds into the company.

THE DIRECT-LABOR BUDGET

Once a company has determined the number of units of production, it calculates the number of direct-labor hours needed. A company states this budget in the number of units and the total number of dollar costs. A company may sort and display labor-hours using these parameters:

TYPE OF OPERATION.

A company segregates employees according to the type of work they do regardless of the products. For example, a company will add up the costs for all assemblers even though they assemble different products.

DIRECT-LABOR CLASSIFICATIONS.

This method sorts labor by the production process. It focuses on the different types of employees working on one product. For example, a company constructs a budget showing the labor costs for all employees working on the same product, regardless of their role.

LABOR STATUS.

This method classifies employees by seniority, level of skill, union affiliation, and the like. A company uses this information to better understand the relationships between labor, skills, experience, and production costs. This information assists management in organizing the labor force more efficiently.

COST CENTERS.

A company using the cost center approach to organization gives each unit of the company the responsibility of controlling its labor costs. Each unit, therefore, is empowered to take corrective action if problems arise in meeting the budget's goals.

THE PRODUCTION OVERHEAD BUDGET

A company generally includes all costs, other than materials and direct labor, in the production overhead budget. Because of the diverse and complex nature of business, production overhead contains numerous items. Accounting lists some of the more common ones:

- Indirect materials—factory supplies that are used in the process but are not an integral part of the final product, such as parts for machines and safety devices for the workers; materials that are an integral part of the final product but difficult to assign to specific products, for example, adhesives, wire, and nails.

- Indirect labor costs—supervisors' salaries and salaries of maintenance, medical, and security personnel.

- Plant occupancy costs—rent or depreciation on buildings, insurance on buildings, property taxes on land and buildings, maintenance and repairs on buildings, and utilities.

- Machinery and equipment costs—rent or depreciation on machinery, insurance and property taxes on machinery, and maintenance and repairs on machinery.

- Cost of compliance with federal, state, and local regulations—meeting safety requirements, disposal of hazardous waste materials, and control over factory emissions (meeting class air standards).

If any one cost traverses the various budgets listed in Table A, the company would apportion that cost to reflect the benefits derived by the participating budgets.

BUDGET OF COST OF GOODS SOLD

At this point the company has projected the number of units it expects to sell and has calculated all the costs associated with the production of those units. The company will sell some units from the preceding period's inventory, others will be goods previously in process, and the remainder will be produced. After deciding the most likely mix of units, the company constructs the budget of the cost of goods sold by multiplying the number of units by their production costs.

ADMINISTRATIVE EXPENSE BUDGET

In the administrative expense budget the company presents how much it expects to spend in support of the production and sales efforts. The major expenses accounted for in the administrative budget are: officers' salaries, office salaries, employee benefits for administrative employees, payroll taxes for administrative employees, office supplies and other office expenses supporting administration, losses from uncollectible accounts, research and development, mortgage payments, bond interest and property taxes, and consulting and professional services.

Generally, these expenses vary little or not at all for changes in the production volume that fall within the budgeted range. Therefore, the administrative budget is a fixed budget. There are some expenses, however, that can be adjusted during the period in response to changing market conditions.

A company may easily adjust some costs, such as consulting services, R&D, and advertising, because they are discretionary costs. Discretionary costs are partially or fully avoidable if their impact on sales and production is minimal. A company, however, cannot avoid such costs as mortgage payments and property. These committed costs are contractual obligations to third parties who have an interest in the company's success. Finally, a company has variable costs that it adjusts in light of cash flow and sales demand. These costs include such items as supplies, utilities, and the purchase of office equipment.

BUDGETED INCOME STATEMENT

A budgeted income statement combines all the preceding budgets to show expected revenues and expenses. To arrive at the net income for the period, the company includes estimates of sales returns and allowances, interest income, bond interest expense, the required provision for income taxes, and a number of nonoperating income and expenses, such as dividends received, interest earned, nonoperating property rental income, and other such items. Net income is a key figure in the profit plan for it reflects how a company commits the majority of its talent, time, and resources.

FINANCIAL BUDGET

The financial budget contains projections for cash and other balance sheet items—assets and liabilities. It also includes the capital expenditure budget (see Table A). It presents a company's plans for financing its operating and capital investment activities. The capital expenditure budget relates to purchases of plant, property, or equipment with a useful life of more than one year. On the other hand, the cash budget, the budgeted balance sheet, and the budgeted statement of cash flows deal with activities expected to end within the 12-month budget period.

CAPITAL EXPENDITURES BUDGET

Capital expenditures budgets outline major investment goals often over a 5- to 10-year period. Companies rely on capital budgeting to identify, evaluate, plan, and finance major investment projects through which it converts cash (short-term assets) into long-term assets. A company uses these new assets, such as computers, robotics, and modern production facilities, to increase productivity, increase market share, and bolster profits. A company purchases these new assets as alternatives to holding cash because it believes that, over the long term, these assets will increase the wealth of the business more rapidly than cash balances. Therefore, the capital expenditures budget is crucial to the overall budget process.

Capital budgeting seeks to make decisions in the present that determine, to a large degree, how successful a company will be in achieving its goals and objectives in the years ahead. Capital budgeting differs from the other financial budgets in that:

- Capital expenditures require relatively large commitments of resources whose dollar value may exceed annual net income.

- Capital expenditures extend beyond the 12-month planning horizon of the other financial budgets. To replace equipment may take 18 months. To build a new plant could involve years of planning and construction.

- Capital expenditures involve greater operating risks. A company encounters more difficulties in the long-term projecting of revenues, expenses, and cost savings. In addition, capital projects divert employee energies away from daily operations.

- Capital expenditures increase the financial risks by adding long term liabilities. A company's short-term liabilities, in the form of mortgage or bond interest, increase long before the project becomes an earning asset.

- Capital expenditures require clear policy decisions that are in full agreement with the company's goals since a company has less flexibility to modify or cancel a project in midstream without serious potential consequences.

THE CASH BUDGET

In the cash budget a company estimates all expected cash flows for the budget period by: stating the cash available at the beginning of the period, adding cash from sales and other earned income to arrive at the total cash available, and subtracting the projected disbursements for payables, prepayments, interest and notes payable, income tax, etc.

The cash budget is an indication of the company's liquidity or its availability of cash, and, therefore, is a very useful tool for effective management. Although profits drive liquidity, they do not necessarily have a high correlation. Often when profits increase, collectibles increase at a greater rate. As a result, liquidity may increase very little or not at all, making the financing of expansion difficult, and the need for short-term credit necessary.

Managers optimize cash balances by having adequate cash to meet liquidity needs, and by investing the excess until needed. Since liquidity is of paramount importance, a company prepares and revises the cash budget with greater frequency than other budgets. For example, weekly cash budgets are common in an era of tight money, slow growth, or high interest rates.

THE BUDGETED BALANCE SHEET

A company derives the budgeted balance sheet, often referred to as the budgeted statement of financial position, from the budgeted balance sheet at the beginning of the budget period and the expected changes in the account balances reflected in the operating, capital expenditure, and cash budgets. (Since a company prepares the budgeted balance sheet before the end of the current period, it uses an estimated beginning balance sheet.)

The budgeted balance sheet is a statement of the assets and liabilities the company expects at the end of the period. The budgeted balance sheet is more than a collection of residual balances resulting from the foregoing budget estimates. During the budgeting process, management ascertains the desirability of projected balances and account relationships. The outcome of this level of review may require management to reconsider plans that seemed reasonable earlier in the process.

BUDGETED STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS

The final phase of the master plan is the budgeted statement of cash flows. This statement anticipates the timing of the flow of cash revenues into the business from all resources, and the outflow of cash in the form of payables, interest expense, tax liabilities, dividends, capital expenditures, and the like.

The statement of cash flows includes:

- The amount of cash the company will receive from all sources, including nonoperating items, creditors, and the sale of stocks and assets. The company includes only those credit sales for which it expects to receive at least partial payment.

- The amount of cash the company will pay out for all activities, including dividend payments, taxes, and bond interest expense.

- The amount of cash the company will net from its operating activities and investments.

The net amount is a clear measure of the ability of the business to generate funds in excess of cash outflows for the period. If anticipated cash is less than projected expenses, management may decide to increase credit lines or to revise its plans. Note that net cash flow is not the same as net income or profit. Net income and profit factor in depreciation and nonoperating gains and losses that are not cash-generating items.

SUMMARY

Budgeting is the process of planning and controlling the utilization of assets in business activities. It is a formal, comprehensive process that covers every detail of sales, operations, and finance, thereby providing management with performance guidelines. Through budgeting, management determines the most profitable use of limited resources. Used wisely, the budgeting process increases management's ability to more efficiently and effectively deploy resources, and to introduce modifications to the plan in a timely manner.

SEE ALSO : Accounting ; Capital Budget ; Cash Flow Statement ; Financial Statements ; Income Statement

[ Roger J. AbiNader ,

updated by Karl Heil

FURTHER READING:

Finney, Robert G. Powerful Budgeting for Better Planning and Management. New York: AMACOM, 1993.

Meigs, Robert F., et al. Accounting: The Basis for Business Decisions. 11 th ed. Boston: Irwin/McGraw-Hill, 1999.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: