BUSINESS PLANNING

Business planning is a management-directed process of identifying long-term goals for a business or business segment, and formulating realistic strategies for reaching those goals. Through planning, management decides what objectives to pursue during a future period, and what actions to undertake to achieve those objectives. Plans may be broad and encompass the entire enterprise, like a plan to double corporate profits, or they may concentrate on certain functional domains, such as information technology planning. Business planning may also entail developing contingency plans of what to do if some goals prove unattainable along the way or of how the business would survive a crisis, e.g., data center failure, natural disaster, and so forth.

Successful business planning requires concentrated time and effort in a systematic approach to answer three basic questions:

- Where is the business enterprise today?

- Where does management want to be in the future?

- How can the business accomplish this?

In answering the first question management assesses the present situation and its implications for future developments. Through planning, management concerns itself with the future implications of current decisions it is about to make, and considers how these decisions limit the scope of future actions. The second question anticipates future profitability and market conditions, and leads management to determine pragmatic objectives and goals. Finally, management outlines a course of action and analyzes the financial implications of those actions. Often management will specify measurable outcomes along the way that will demonstrate whether the business is progressing toward the goals as planned. From an array of alternatives, management distills a broad set of interrelated choices to form its long-term strategy. It is in the annual budgeting process that management develops detailed, short-term plans that guide the day-to-day activities meant to attain the objectives and goals.

PURPOSE AND FUNCTION OF PLANNING

Effective planning enables management to craft its own future, at least to some degree, rather than merely reacting to external events without a coherent motivating force for corporate actions. Management sets objectives and charts a course of action so as to be proactive rather than reactive to the dynamics of the business environment. The assumption, of course, is that through its continuous guidance management can enhance the future state of the business.

PLANNING CONCEPTS

Business planning is a systematic and formalized approach to accomplishing the planning, coordinating, and control responsibilities of management. It involves the development and application of: long-range objectives for the enterprise; specific goals to be attained; long-range profits plans stated in broad terms; adequate directions for formulating annual, detailed budgets, defining responsibility centers, and establishing control mechanisms; and evaluative methods and procedures for making changes when necessary.

Implicit in the process are the following concepts:

- The process must be realistic, flexible, and continuous.

- Management plays a critical role in the long-term success of a business.

- Management must have vision and good business judgment in order to plan for, manipulate, and control, in large measure, the relevant variables that affect business performance.

- The process must follow the basic scientific principles of investigation, analysis, and systematic decision making.

- Profit-planning and control principles and procedures are applied to all phases of the operations of the business.

- Planning is a total systems approach, integrating all the functional and operational aspects of the business.

- Wide participation of all levels of management is fundamental to effective planning.

- Planning has a unique relationship to accounting which collects, books, analyzes, and distributes data necessary for the process.

- Planning is a broad concept that includes the integration of numerous managerial approaches and techniques such as sales fore-casting, capital budgeting, cash flow analysis, inventory control, and time and motion studies.

A business plan, then, incorporates management objectives, effective communications, participative management, dynamic control, continuous feedback, responsibility accounting, management by exception, and managerial flexibility.

BENEFITS OF PLANNING

Planning provides a means for actively involving personnel from all areas of the business enterprise in the management of the organization. Company-wide participation improves the quality of the plans.

Employee involvement enhances their overall understanding of the organization's objectives and goals. The employees' knowledge of the broad plan and awareness of the expected outcomes for their responsibility centers minimizes friction between departments, sections, and individuals. Involvement in planning fosters a greater personal commitment to the plan and to the organization. These positive attitudes improve overall organizational morale and loyalty.

Managerial performance can also benefit from planning, although care must be taken that planning does not become an empty task managers do periodically and ignore the rest of the time. Successful planning focuses the energies and activities of managers in the utilization of scarce resources in a competitive and demanding marketplace. Able to clearly identify goals and objectives, managers perform better, are more productive, and their operations are more profitable. In addition, planning is a mental exercise from which managers attain experience and knowledge. It prepares them for the rigors of the marketplace by forcing them to think in a future- and contingency-oriented manner.

DRAWBACKS TO PLANNING

Seemingly there would be no downside to planning; however, organizations may engage in lengthy and labor-intensive planning activities without gaining much, if anything, for their investments. By one estimate, some companies may spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on labor for so-called planning activities, yet nothing of strategic importance results from all of the planners' efforts. Companies with bureaucratic planning programs are particularly susceptible to wasting management's time with planning activities that do little to actually further the business. Sometimes the managers charged with planning lack the necessary knowledge or clout in the organization to make any strategic impact; clearly their time is wasted. In other cases, middle managers may be asked to create periodic departmental "plans" that are nothing more than an elaborate restatement of what they're already doing. Similarly, employees and management may engage in protracted planning sessions that aren't adequately focused on concrete business development strategies, but on speculation, clarification of existing policy, or trivial issues. While management and employees need forums for dialogue, companies may be cloaking such dialogues with the moniker and resources that should be reserved for true strategic development.

To avoid such pitfalls, successful companies strive to keep planning activities sharply focused and in the hands of the appropriate decision makers. Their planning is grounded in pragmatic and business-critical performance issues, such as profitability, return on investment, and cost containment.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Planning has been a part of economic history for almost 5,000 years. Evidence suggests that in an agrarian economy most economic activity was governed by changing seasons and ran in short-term cycles of less than one year. Long-range planning of more than one year, although notable, was conducted by a few institutions and individuals. Extant records indicate the extensive use of plans in empire building, road paving, war waging, temple construction, and the like. Not until the Industrial Revolution in the United States, thought to have begun about 1860, did the scope and style of economic activity dramatically change.

The first major industrial expansion began with factories in the northeast and the canals throughout the middle-Atlantic states. Owners and developers employed long-term plans for the construction of their enterprises, but not necessarily for their operation. For the most part, they made decisions without the benefit of research and analysis. Since these businesses served regional markets, on-the-spot decisions sufficed as a highly expanding market masked poor business planning. With the subsequent development of a national rail system, economic activity became both more urban and national in scope. The rapid growth of the economy and the complex business systems it spawned called for new and sophisticated management techniques.

John Stevens (1749-1838) kicked off the boom in railroads in 1830. Track mileage expanded from about 6,000 miles in 1848 to over 30,000 miles by 1860. The surveying of lands, the engineering designs, and laying of track involved enormous amounts of long-range planning and implementation. The mere territorial expanse of the railroad required long-term financing and control of operations. The complexities of scheduling over long distances, the coordination of routes, and the maintenance of stations became overly complicated. With no historic model from which to develop paradigms, rail company managers eagerly sought solutions. The lack of speedy travel and communications did not bode well.

With Samuel F.B. Morse's (1791-1872) invention of the telegraph in 1844, managers gained the ability to coordinate and to communicate with unprecedented speed and efficiency. The era of the railroad hastened industrial development so that, by the last quarter of the 19th century, manufacturing replaced agriculture as the dominant national industry.

American business fell under the leadership of the "captains of industry" such as John D. Rockefeller (1834-1937) in oil, James B. Duke (1856-1925) in tobacco, Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919) in steel, and Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877) in steamships and railroads. These men represented the burgeoning capitalist entrepreneur pursuing profit and self-interest above other national and cultural concerns. Their giant companies were characterized by new forms of organizations and new marketing methods. They formed distributing and marketing organizations on a national, rather than regional, basis. By 1890 previous management methods no longer applied to U.S. industry, and the study of business activities began in earnest. The corporate giant required new methods of decision making since on-the-spot decisions no longer served the interests of the long-term viability of the enterprise.

With the onset of the Great Depression, companies recognized the need for professional managers who applied scientific principles in the planning and control of an enterprise. Business planning, however, as it is known today, was not popular in the United States until after World War II. A limited survey conducted in 1929 found that about half of the respondents made plans in some detail up to one year in advance. Fewer than 15 percent, however, made plans for as long as five years. A 1956 survey found that 75 percent of responding organizations planned more than one year ahead. A more comprehensive survey in 1973 found that 84 percent did some type of long-range planning of up to three years. Little change was found in follow-up surveys conducted in 1979 and 1984.

The increase in the use of formal long-range plans reflects a number of significant factors:

- Competitors engage in long-range planning.

- Global economic expansion is a long-range effort.

- Taxing authorities and investors require more detailed reports about future prospects and annual performance.

- Investors assess risk/reward according to long-range plans and expectations.

- Availability of computers and sophisticated mathematical models add to the potential and precision of long-range planning.

- Expenditures for research and development increased dramatically, resulting in the need for longer planning horizons and huge investments in capital equipment.

- The postwar economy has suffered few cataclysmic events. Steady economic growth has made longer-term planning more realistic.

THE PARTICIPANTS

Planning is essentially a managerial function. Although the top executives initiate and direct the planning process, they involve as many key employees and decision makers as needed. Often, outside consultants assist the following personnel in the planning process:

The board of directors defines the purposes and direction of the business entity; the executive managers formulate objectives and goals; the chief executive officer gives direction and sets standards; the chief financial officer coordinates financial and accounting information with the treasurer, controller, and budget officer assisting; the chief operating officer provides production information; counsel provides a legal interpretation to proposed activities; also assisting are sales and marketing executives, department and division managers, line supervisors, and other employees who clarify the realities of the day-to-day routines.

Planning is an inclusive, coordinated, synchronized process undertaken to attain objectives and goals.

THE PLANNING HORIZON

There are two main types of plans. The first is long range, extending beyond one year and, normally, less than ten years. Often called the strategic plan or investment plan, it establishes the objectives and goals from which short-range plans are made. Long-range plans support the organizational purpose by providing clear statements of where the organization is going.

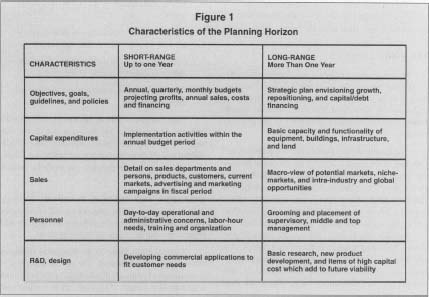

The second is short range, covering a period of up to one year. Short-range plans are derived from an in-depth evaluation of the long-range plan. The annual budget is a quantified expression of the enterprise's plans for the fiscal year. It generally is divided into quarters, and is used to guide and control day-to-day activities. It is often called the tactical plan because it sets priorities, in the near term, for the long-range plans through the allocation of resources to specific activities. See Figure I for more detail.

FUNCTIONAL PLANS.

Plans are often classified by the business function they provide. All functional plans emanate from the strategic plan and define themselves in the tactical plans. Four common functional plans are:

- Sales and marketing: for developing new products and services, and for devising marketing plans to sell in the present and in the future.

- Production: for producing the desired product and services within the plan period.

- Financial: for meeting the financing needs and providing for capital expenditures.

- Personnel: for organizing and training human resources.

Each functional plan is interrelated and interdependent. For example, the financial plan deals with moneys resulting from production and sales. Well-trained and efficient personnel meet production schedules. Motivated salespersons successfully market products.

STRATEGIC AND TACTICAL PLANNING.

Strategic plans cover a relatively long period and affect every part of the organization by defining its purposes and objectives and the means of attaining them.

Tactical plans focus on the functional strategies through the annual budget. The annual budget is a compilation of many smaller budgets of the individual responsibility centers. Therefore, tactical plans deal with the micro-organizational aspects, while strategic plans take a macro-view.

STEPS IN THE PLANNING PROCESS

The planning process is directly related to organizational considerations, management style, maturity of the organization, and employee professionalism. These factors vary among industries and even among similar companies. Yet all management, when applying a scientific method to planning, perform similar steps. The time spent on each step will vary by company. Completion of each step, however, is prerequisite to successful planning. The main steps are:

- Conducting a self-audit to determine capabilities and unique qualities

- Evaluating the business environment for possible risks and rewards

- Setting objectives that give direction

- Establishing goals that quantify objectives and time-frames

- Forecasting market conditions that affect goals and objectives

- Stating actions and resources needed to accomplish goals

- Evaluating proposed actions and selecting the most appropriate

- Instituting procedures to control the implementation and execution of the plan

Characteristics of the Planning Horizon

THE SELF-AUDIT.

Management must first know the functional qualities of the organization, and what business opportunities it has the ability to exploit. Management conducts a self-audit to evaluate all factors relevant to the organization's internal workings and structure.

A functional audit explores such factors as:

- Sales and marketing: competitive position, market share and position, quality and service

- Production: operational strategies, productivity, use and condition of equipment and facilities, maintenance costs

- Financial: capital structure, financial resources, credit facilities, investments, cash flow, working capital, net worth, profitability, debt service

- Personnel: quantity and quality of employees, organizational structure, decision making policies and procedures.

THE BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT.

Management surveys the factors that exist independently of the enterprise but which it must consider for profitable advantage. Management also evaluates the relationships among departments in order to coordinate their activities. Some general areas of the external environment considered by management are:

- Demographic changes: sex, age, absolute numbers, location, movement, ethnicity

- Economic conditions: employment level, regional performance, sex, age, wage levels, spending patterns, consumer debt

- Government fiscal policy and regulations: level of spending and entitlements, war and peace, tax policies, environmental regulations

- Labor supply: age, sex, education, cultural factors, work ethics, training

- Competition: market penetration and position, market share, commodities or niche product

- Vendors: financial soundness, quality and quantity of product, research and development capabilities, alternatives, foreign, domestic, just-in-time capabilities.

SETTING OBJECTIVES AND ESTABLISHING GOALS.

The setting of objectives is a decision making process that reflects the aims of the entire organization. Generally, it begins at the top with a clear statement of the organization's purpose. If well communicated and clearly defined down through the hierarchy, this statement becomes the basis for short-range objectives in the annual budget.

Management articulates the overall goals to and throughout the organization in order to coordinate all business activities efficiently and effectively. It does this by:

- Formulating and distributing a clear, concise statement of the central purpose of the business

- Leading in the formulating of long-range organizational goals

- Coordinating the activities of each department and division in developing derivative objectives

- Ensuring that each subdivision participates in the budget process

- Directing the establishment of short-term objectives through constructing the annual budget

- Evaluating actual results on the basis of the plans

The organization must know why it exists and how its current business can be profitable in the future. Successful businesses define themselves according to customer needs and satisfaction with products and services.

Management identifies the customers, their buying preferences, product sophistication, geographical locations, and market level. Analyzing this data in relation to the expected business environment, management determines the future market potential, the economic variables affecting this market, potential changes in buying habits, and unmet needs existing now and those to groom in the future.

In order to synchronize interdepartmental planning with overall plans, management reviews each department's objectives to ensure that they are subordinate to the objectives of the next higher level.

Management quantifies objectives by establishing goals that are: specific and concrete, measurable, time-specific, realistic and attainable, open to modification, and flexible in their adaptation.

Because goals are objective-oriented, management generally lists them together. For example:

- Profitability. Profit objectives state performance in terms of profits, earnings, return on investments, etc. A goal might call for an annual increase in profits of 15 percent for each of the next five years.

- Human resources. This broad topic includes training, deployment, benefits, work issues, and qualifications. In an architectural consulting firm, management might have a goal of in-house CAD training for a specified number of hours in order to reach a certain level of competence.

- Customer service. Management can look at improvements in customer service by stating the number of hours or the percentage of complaints it seeks to reduce. The cost or cost savings are stated in dollar terms. If the business sells service contracts for its products, sales goals can be calculated in percentage and dollar increases by type and level of contract.

- Social responsibility. Management may desire to increase volunteerism or contributions to community efforts. It would calculate the number of hours or dollars within a given time frame.

FORECASTING MARKET CONDITIONS.

Forecasting methods and levels of sophistication vary greatly. Each portends to assess future events or situations that will affect either positively or negatively the business's efforts. Managers prepare forecasts to determine the type and level of demand for products currently produced or that can be produced. Management analyzes a broad spectrum of economic, demographic, political, and financial data for indications of growing and profitable markets.

Forecasting involves the collection and analysis of hard data, and their interpretation by managers with proven business judgment.

Individual departments such as sales, and divisions such as manufacturing, also engage in forecasting. Sales forecasting is essential to setting production volume. Production forecasting determines the materials, labor, and machines needed.

STATING ACTIONS AND RESOURCES REQUIRED.

With the objectives and forecasts in place, management decides what actions and resources are necessary in order to bring the forecast in line with the objectives. The basic steps management plans to take in order to reach an objective are its strategies.

Strategies exist at different levels in an organization and are classified according to the level at which they allocate resources. The overall strategy, often referred to as the grand strategy, outlines how to pursue objectives in light of the expected business environment and the business's own capabilities. From the overall strategy, managers develop a number of more specific strategies.

- Corporate strategies address what business(es) an organization will conduct and how it will allocate its aggregate resources, such as finances, personnel, and capital assets. These are long-term in nature.

- Growth strategies describe how management plans to expand sales, product line, employees, capacity, and so forth. Especially necessary for dynamic markets where product life cycles are short, growth strategies can be (a) in the expansion of the current business line, (b) in vertical integration of suppliers and end-users, and (c) in diversifying into a different line of business.

- Stability strategies reflect a management satisfied with the present course of action and determined to maintain the status quo. Successful in environments changing very slowly, this strategy does not preclude working toward operational efficiencies and productivity increases.

- Defensive strategies, or retrenchment, are necessary to reduce overall exposure and activity. Defensive strategies are used: to reverse negative trends in profitability by decreasing costs and turning around the business operations; to divest part or all of a business to raise cash; and to liquidate an entire company for an acceptable profit.

- Business strategies focus on sales and production schemes designed to enhance competition and increase profits.

- Functional strategies deal with finance, marketing, personnel, organization, etc. These are expressed in the annual budget and address day-to-day operations.

EVALUATING PROPOSED PLANS.

Management undertakes a complete review and evaluation of the proposed strategies to determine their feasibility and desirability. Some evaluations call for the application of good judgment—the use of common sense. Others use sophisticated and complex mathematical models.

Prior to directing the development of a profit budget for the upcoming annual period, management resolves issues related to the internal workings of the organization from a behavioral point of view. For example:

- Ensuring managerial sophistication in the application of the plans

- Developing a realistic profit plan, and assigning adequate responsibility and control

- Establishing appropriate standards and objectives

- Communicating the attitudes, policies, and guidelines to operational and administrative personnel

- Attaining managerial flexibility in the execution of the plans

- Evaluating and updating the system to harmonize with the changing operational and business environments

ASSESSING ALTERNATIVE STRATEGIC PLANS.

Because of the financial implications inherent in the allocation of resources, management approaches the evaluation of strategic alternatives and plans using comprehensive profit planning and control. Management quantifies the relevant strategies in pro forma statements that demonstrate the possible future financial impact of the various courses of action available. Some examples of pro forma statements are: budgets, income statements, balance sheets, and cash flow statements.

The competing strategic long-range plans constitute simulation models that are quite useful in evaluating the financial effects of the different alternatives under consideration. Based on different sets of assumptions regarding the interaction of the entity with the outside world, these plans propose various scenarios of sales, production costs, profitability, and viability. Generally categorized as normal (expected results), above normal (best case), and below normal (worst case), the competing plans project possible outcomes at input/output levels within specified operating ranges attainable within the fiscal year.

In developing and using planning and control programs, management benefits from the realization that:

- Profit plans do not replace management and administration, but are tools for managers with which to keep business activities on track.

- Vigilance and consistent review are necessary because the plans are made in the present about future events and outcomes. Management's plans are highly dependent on the quality of its estimates and judgment. Therefore, it must be flexible in utilizing the results of models and in interpreting the actual results.

- Dynamic management continuously adapts plans to a changing environment, seeks improvements, and educates the organization.

- Profit plans do not implement themselves. Management must direct, coordinate, and control relevant actions. Management must have a sophisticated understanding of the plans, be convinced of their importance, and meaningfully participate in their implementation.

Management bases its choices on the overall return on investment (ROI) objective, the growth objective, and other dominant objectives. Management selects courses of action relative to pricing policy, advertising campaigns, capital expenditure programs, available financing, R&D, and so forth.

In choosing between alternative plans, management considers

- the volume of sales likely attainable

- the volume of production currently sustainable

- the size and abilities of the sales forces

- the quality and quantity of distribution channels

- competitors' activities and products

- the pace and likelihood of technological advances

- changes in consumer demand

- the costs and time horizon of implementing changes

- capital required by the plan

- the ability of current employees to execute proposed plans.

CONTROLLING THE PLAN THROUGH

THE ANNUAL BUDGET

Control of the business entity is essentially a managerial and supervisory function. Control consists of those actions necessary to assure that the entity's resources and operations are focused on attaining established objectives, goals, and plans. Control compares actual performance to predetermined standards and takes action when necessary to correct variances from the standards.

Control, exercised continuously, flags potential problems so that crises may be prevented. It also standardizes the quality and quantity of output, and provides managers with objective information about employee performance.

In recent years some of these functions have been assigned to the point of action, the lowest level at which decisions are made. This is possible because management carefully grooms and motivates employees through all levels to accept the organization's way of conducting business.

The planning process provides for two types of control mechanisms:

- Feedforward: providing a basis for control at the point of action (the decision point); and

- Feedback: providing a basis for measuring the effectiveness of control after implementation.

Management's role is to feedforward a futuristic vision of where the company is going and how it is to get there, and to make purposive decisions coordinating and directing employee activities. Effective management control results from leading people by force of personality and through persuasion; providing and maintaining proper training, planning, and resources; and improving quality and results through evaluation and feedback.

Effective management means goal attainment. In a profit-making business or any income-generating endeavor, success is measured in dollars and dollar-derivative percentages. The comparison of actual results to budget expectations becomes a formalized, routine process that:

- measures performance against predetermined objectives, plans, and standards

- communicates results to appropriate personnel

- analyzes variations from the plans in order to determine the underlying causes

- corrects deficiencies and maximizes successes

- chooses and implements the most promising alternatives

- implements follow-up to appraise the effectiveness of corrective actions

- solicits and encourages feedback to improve ongoing and future operations

THE ROLE OF ACCOUNTING

Accounting plays a key role in all planning and control because it: provides data necessary for use in preparing estimates; analyzes and interprets these data; designs and operates the budgeting and control procedures; and consolidates and reviews budgetary proposals.

DATA COLLECTION.

Accounting is at the heart of control since it compiles records of the costs and benefits of the company's activities in considerable detail, establishes a historical basis upon which to base forecasts, and calculates performance measures.

DATA ANALYSIS.

Accounting's specialty is in the control function, yet their analysis is indispensable to the planning process. Accounting adjusts and interprets the data to allow for changes in company-specific, industry-specific, and economy-wide conditions.

BUDGET AND CONTROL ADMINISTRATION.

Accountants play a key role in designing and securing support for the procedural aspects of the planning process. In addition, they design and distribute forms for the collection and booking of detailed data on all aspects of the business.

CONSOLIDATION AND REVIEW.

Although operating managers have the main responsibility of planning, accounting compiles and coordinates the elements. Accountants subject proposed budgets to feasibility and profitability analyses to determine conformity with accepted standards and practices.

ENTERPRISE RESOURCE PLANNING (ERP)

Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems are an important business-planning and management tool that emerged in the mid-1990s. ERP involves integrating information systems from diverse functional areas using a single software tool. The software enables information management within and across such departments as:

- human resources

- marketing

- purchasing

- accounting

- production

- engineering

ERP systems are usually customized at least to some degree for the particular company using them. Once the system is up and running, which is often a major undertaking, management should be able to obtain more comprehensive and up-to-date information about key business areas and channel that knowledge into future plans. ERP systems are intended to enable and promote cross-functional thinking in the organization, as well as to reduce data duplication and discrepancies. As a result, ERP systems benefit planning functions as well as tracking and day-to-day operations.

SUMMARY

Business planning is more than simply forecasting future events and activities. Planning is a rigorous, formal, intellectual, and standardized process. Planning is a dynamic, complex decision-making process through which management conceives of—and prepares for—the business's future.

Management evaluates and compares different possible courses of action it believes will be profitable to meet corporate objectives. It employs a number of analytical tools and personnel to prepare the appropriate data, make forecasts, construct plans, evaluate competing plans, make revisions, choose a course of action, and implement that course of action. After implementation, managerial control consists of efforts to prevent unwanted variances from planned out-comes, to record events and their results, and to take action in response to this information.

SEE ALSO : Break-Even Analysis ; Business Conditions ; Strategy ; Strategy Formulation

[ Roger J. AbiNader ]

FURTHER READING:

Campbell, Andrew. "Tailored, Not Benchmarked." Harvard Business Review, March 1999.

"Conducting Business Technology Planning." Managing Office Technology, July 1997.

Egan, Gerard. Adding Value: A Systematic Guide to Business-Driven Management and Leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993.

Goldstein, Leonard, Timothy Nolan, and J. William Pfeiffer. Applied Strategic Planning. New York: McGraw Hill, 1993.

Myers, Kenneth H. Total Contingency Planning for Disasters. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1996.

Napier, Rod, et al. High Impact Tools and Activities for Strategic Planning. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998.

Rodetis, Susan. "Can Your Business Survive the Unexpected?" Journal of Accountancy, February 1999.

Steiner, George Albert. Strategic Planning: What Every Manager Must Know. New York: Free Press, 1997.

You have done a wonderful job and these articles are really very helpful. These are really up to the mark and clear all the douts about the topic.

Regards

KV