SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS

"Investments" refers to the process of applying resources so as to increase wealth. Direct investment is the actual acquisition and management of assets by the individual. For many assets such direct investment is cumbersome and unavailable to smaller investors. Direct investments are often difficult to manage, are of limited liquidity, and require expertise on the part of the investor. For larger direct investments, the required concentration of investor wealth in a few ventures increases risk. Consequently, investors using this direct form of investment demand higher return and are hesitant to undertake new ventures without substantial safeguards. If this were the only form of investment, formation of new ventures would be difficult and economic growth would be slow.

Many of these problems can be reduced or avoided by indirect investment through securities. Securities are instruments that represent an interest in, or claim on, other assets. Use of securities separates ownership from possession and management of assets. This separation allows widespread ownership and easy transfer, dispersion of wealth over investments, use of professional management, and access to broader sources of capital. This in turn helps create capital markets with more efficient allocation of resources, encouraging economic growth. The advantages of the security form of investment are not limited to physical assets. The appeal of securities over direct acquisition is evidenced by the recent "securitization" of financial assets. In this process normally illiquid assets are pooled, and shares in this diversified pool are then issued.

Securities simplify the investment process, but do not remove all problems. Analysis of securities, and their combination into portfolios, is a complicated problem requiring a high level of expertise. The investor must be concerned with both the level of and uncertainty about the anticipated returns. Investment theory is not so much directed toward the actual physical assets, or even to the predicted cash flows from the investments. Instead it is concerned with investment return, which is increasingly treated as a random variable described by a probability distribution. Securities exhibit a "risk return tradeoff"—i.e., assets with greater uncertainty about the actual outcome (higher risk) must on average provide a higher anticipated return to induce investors to accept the risk. Over the period 1926 to 1995, a study by Ibbotson Associates indicated that U.S. Treasury bills (T-bills), the asset class with the most uncertain returns, had an average annual return of 3.7 percent, while small capitalization stocks had the highest uncertainty and an average annual return of 17.7 percent.

As uncertainty of returns increased over asset classes, returns also increased. It is commonly accepted that greater risk accompanies greater anticipated return. Finally, the investor must consider the interactions between securities, combining them into portfolios that reduce risk through diversification.

SECURITIES

An amazing diversity of securities has developed over time, and there are variations on the general types of securities described here. The pace of innovation has increased in recent years with the development of quantitative analysis and investment models. New types of securities are being created, and old types modified, at an unprecedented pace. Financial engineering, which is the design of new and often very complex instruments and strategies, has emerged as a separate new discipline. Some standard forms of securities are apparent, however, and are typically classified according to various common characteristics into equity, fixed income, and derivatives. It should be noted that there are exceptions to every common characteristic—investors must carefully consider each individual security.

FIXED-INCOME SECURITIES—BONDS

Despite the greater publicity given to stock, firms in the United States obtain much more of their financing through issuing bonds. The cash flows to fixed income securities are fixed or specified in advance. In the case of bonds, these cash flows are a contractual obligation. The cash flows are the interest payments, generally paid semiannually, and the repayment of principal at maturity. Thus, a bond with a principal amount of $1,000, a 20-year life, and a 12 percent coupon rate will make 40 semiannual payments of $60, plus one payment of $1,000 at the end of 20 years. The principal amount and the coupon rate are not the price of and rate of return on the bond. The bond must provide the market return available from other, similar bonds. Since the cash flow is fixed, the only way that the rate of return on the bond can adjust to new conditions is through price change. The bond price will increase if interest rates decrease, but will decrease if interest rates increase. The effect of interest rates on prices is greater for longer bonds or for lower coupon bonds. Bondholders thus face "interest rate risk" or "price risk." Since bonds vary as to coupon rate, principal amount, and other features, the bond price is often described in terms of the rate of return or yield of the bond rather than a dollar amount. Zero coupon bonds or "zeroes" are a variant from the usual coupon bonds in that there is no interest payment. Zeroes provide a return by being sold at a discount to the principal amount, and are particularly sensitive to changes in the required rate of return.

Callable bonds can be called in, or repurchased, by the issuing firm. The price at which the forced repurchase is carried out is the principal plus a call premium. The call premium may vary over the life of the bond, typically becoming smaller as maturity nears. This feature is to the benefit of the firm, primarily if the firm desires to refund the issue by replacing it with an issue with lower interest cost. Refunding will occur when recall is to the firm's advantage—i.e., when yields are low. Despite the attraction of receiving the call premium, a call is not welcomed by investors, who face the prospect of being forced to replace the investment with a security of lower yield. Further, the call price becomes in effect an upper limit to the price of the bond. This call risk is disagreeable to investors, so that callable bonds typically have a higher yield than similar noncallable bonds. Bonds are often "call protected" for a certain period to make the feature more acceptable to investors and allow issue at a higher price (lower yield). At the other extreme is the putable bond, which may be sold back to the issuer at the option of the investor. This feature is attractive to investors, and putable bonds will have a lower yield than similar nonputable bonds.

The maturity of a bond issue is a time of some concern. While the firm may be able to make the periodic interest payment, the repayment of principal at principal may be beyond the ability of the firm. Normally, an issue will simply be replaced by a new issue, but this may prove difficult or impossible under some conditions. A sinking fund is a way of avoiding this end of life crisis. Originally, a sinking fund requirement actually created a fund to which the firm made payments, so that all or at least a portion of the maturity payments were provided by the fund. More recent sinking fund provisions usually require that a certain amount of bonds be retired each year. If the bonds are selling below the call price, the requirement will be met through purchase on the open market. If the bonds are above the call price, they will be called. Often the call premium for purchases to meet sinking fund requirements is less than the call premium for refunding. This feature is thus a mixed blessing for investors. On the one hand the possibility of end of life crisis is lessened, the effective life of the issue is shortened, and it is also thought that sinking fund repurchases will support the value of the bonds. On the other hand, the investor faces the possibility of call at a reduced premium.

Because the cash flows are specified and contractual, bonds are considered to be among the safest investments. In addition to interest rate risk and call risk, however, bondholders face default risk and inflation risk. Because the cash flows are fixed in advance and will not change if costs rise, bondholders are exposed to the risk of loss of purchasing power resulting from inflation. Default may be total or may be a partial interruption in the specified cash flows, and even in bankruptcy bondholders typically recover at least a portion of principal. Risk of default is called "credit risk" or "quality risk," and is reflected in bond quality ratings, which are provided for a fee by independent external rating agencies. Bonds are classified by the rating agencies into broad classes depending on the probability of default at the time of the rating. A particular bond issue may be rated by several agencies, and ratings are normally consistent. Bond ratings may be reevaluated and changed if conditions change. The bond rating is an important determinant of the required yield, and a rating change can significantly affect the bond price.

The legal document under which the bond is issued is called the indenture, and this document spells out the characteristics and arrangements that affect the value and risk of the bond. There are a large variety of characteristics that have been written into the bond indenture, so that individual bond issues within a given type can vary widely. In some cases the bond indenture will contain various restrictions intended to reduce the risk of default (increase the bond quality). These restrictions often take the form of minimum required accounting ratios, although other restrictions on management occur.

CORPORATE BONDS.

Corporates are simply bonds issued by corporations, and are typically callable. The credit risk of a corporate bond is a reflection of the viability of the issuer and the arrangements contained in the indenture, and variations are wide. One important characteristic of a bond is the collateral. Mortgage bonds are secured by a claim on a specific asset, usually real property. Mortgage bonds may be described as "open end," "limited open end," or "closed end," depending on the extent to which the collateral can be used as security for other issues. Equipment trust certificates are a variation of mortgage bond using equipment as security, while collateral trust certificates use securities of other entities as collateral. In bankruptcy, the asset would be sold and the proceeds used to pay the claims of the mortgage bondholders. Any excess proceeds would go the claimants of the next highest priority. If the proceeds were insufficient, the mortgage bondholders' claims for the balance would simply be joined to the next highest priority claimants, typically holders of debenture bonds. Debenture bonds are secured by a general, nonspecific claim on the firm's assets. In some cases the security of mortgage bonds or debentures may be augmented by the existence of subordinated debentures. In case of bankruptcy the holders of subordinated debentures must subordinate their claims to another specific class of bonds, and will receive payments only after the claims of the other class have been met in full.

Convertible corporate bonds are bonds that can be converted into the common stock of the issuing firm. They are considered attractive because the fixed cash flows set a minimum return, but the conversion allows the bondholder to participate in increases in stock price. Because of the attraction of this feature, convertible bonds sell at a higher price and so have a lower yield.

GOVERNMENT BONDS.

Government bonds are securities issued by the U.S. Treasury and by U.S. government agencies. Treasury securities are obligations of the U.S. government, and are considered to have no credit risk. Treasury securities with original maturities ranging up to 10 years are called U.S. Treasury notes, while Treasury securities with original maturities from 10 to 30 years are called U.S. Treasury bonds. Treasury bonds are sometimes callable in the last 5 years before maturity. Treasury securities enjoy one of the most active markets, and are highly liquid. The market is an over-the-counter market where government securities dealers stand ready to buy or sell, providing continuous quotes.

Notes and bonds are issued on regular cycles for various maturities. Competitive bids specify the yield and the amount of securities desired. Noncompetitive bids specify only the amount of securities desired. The total amount of noncompetitive bids is first subtracted from the size of the offering, and the remaining amount is then allocated among the competitive bids by ascending yield. All noncompetitive bids are then accepted at the average price paid by the competitive bidders. Competitive bidders run the risk of winner's curse (overpaying) or of not having the bid accepted if the price is too low. Noncompetitive bidders avoid the winner's curse of overbidding and know that the order will be filled, but do not know the price and may miss the chance of buying at a low price.

Agencies are bonds issued by government agencies, with fixed interest payments and maturity value. These securities are not technically direct obligations of the U.S. government. Nonetheless, it is widely assumed that the U.S. government would support the obligation, and agency bonds are considered to have very low credit risk.

MUNICIPAL BONDS.

Municipal bonds are issued by state and local governments. Interest payments on municipal bonds are generally exempt from federal taxes, and from state and local taxes for bondholders residing within the state of issue (but not for bondholders residing in other states). Because of this tax-exempt feature, these bonds tend to have a lower pretax yield than taxable bonds. The desirability of these bonds to an investor depends on the tax rate of the investor, with the tax exemption of greater value to investors in higher tax brackets. Capital gains on municipal bonds are fully taxable. It is important to recognize, however, that not all bonds issued by state and local governments qualify for this tax treatment, and the investor is advised to use caution.

General obligation municipal bonds are supported by the full faith and credit of the issuer. In reality, this means that the bonds ultimately rely on the taxing power of the municipality. The credit risk of a given issue is thus a function of the prosperity and existing tax load of the municipality. Revenue municipal bonds, on the other hand, are bonds issued to finance a particular project, such as a bridge or sewer line. Revenue bonds are meant to be paid by the proceeds from the project, such as bridge tolls or fees, and are not backed by the municipality itself. The credit risk of a particular issue depends on the viability of the project being financed. Various maturities are available, usually up to 30 years. Municipals are sometimes issued as serial bonds. A serial bond issue has staggered maturities, so that a certain number of the bonds will mature in any given year. The effect is the same as a sinking fund, except that the maturity of an individual bond is exactly known, and the investor can choose from a variety of maturities.

ASSET-BACKED SECURITIES

Asset-backed securities are backed by a pool of financial assets that, by themselves, are relatively illiquid. The assets are "securitized" by combining them into a portfolio and issuing securities that use the portfolio as collateral. Mortgage-backed securities, or pass-throughs, are securities that represent a claim to proceeds from a pool of mortgages. Ownership of an individual mortgage would be quite risky and would have high default risk, but ownership of a pool spreads default risk over all investors holding securities based on the pool. The cash flows from the instrument are the principal and interest payments of the mortgages, which are passed through to the bondholders. Although the default risk is reduced by the pooling, the cash flows to mortgage-backed securities are uncertain. Mortgagees have the right to repay the mortgages before maturity. Prepayment may result from relocation or similar individual circumstances, or from refinancing of mortgages at lower interest. The effect of the prepayment option is similar to the call feature of corporate bonds, except that it occurs continually in small amounts. The cash flows from mortgage-backed securities have also been repackaged in various ways to appeal to different investors. Other forms of asset-backed securities are backed by automobile loans or credit card receivables.

FIXED-INCOME SECURITIES—PREFERRED

STOCK

Cash flows to preferred stock are also specified in advance. These cash flows take the form of a fixed dividend to be paid at set intervals. While some preferred stock has a maturity with a final payout, often there is no fixed maturity. The stock is said to be preferred for two reasons. The first is that no dividends may be paid on common stock unless the dividend on preferred stock has been paid. Second, in bankruptcy the preferred stockholders have a higher priority for payment than the common stockholders. Balancing these preferences is the characteristic that preferred stock usually has no voting power.

Although the cash flow to preferred stock is very similar to the cash flow to bonds, there is a major difference in the nature of the cash flows to preferred. The dividends are a promise, rather than a contractual obligation. Dividends are declared at the discretion of the directors. The directors have no legal obligation to declare scheduled dividends, and preferred stockholders cannot legally force payment. There are several reasons, however, why it is unlikely that the directors will fail to declare the dividend. First, the dividend is usually cumulative. This means that any undeclared scheduled dividend is not forgotten but is due and payable. Second, no dividends may be paid to common stockholders while preferred dividends are in arrears. Finally, the preferred stockholders are often granted voting power if preferred dividends are in arrears. Thus, theoretically, the directors will declare the dividends, if possible, to avoid the wrath of the now-voting and annoyed stockholders. In reality, given the difficulties of mounting a challenge to an entrenched management, this may not be all that powerful a motivation. It may be that investor antipathy to a firm in arrears on preferred dividends, and the resulting isolation from capital markets, is more important.

It has been suggested that preferred stock may not be a desirable investment for individual investors. This suggestion arises because 70 percent of intra-corporate dividends are excluded from taxable income. This rule arises because, unlike interest on bonds, dividends on preferred stock are not tax deductible to the firm. The earnings behind the preferred dividend face double taxation—once when earned by the firm, and once again when paid to the investor. If the dividend is passed through another firm that then pays the dividend earnings as a dividend, the earnings would have been subject to triple taxation. The tax treatment is intended to reduce this multiple taxation effect. As a result of this tax treatment, the after-tax return on preferred is greater for firms than for individuals. Demand from firms thus results in overpricing from the individual, fully taxable, viewpoint.

EQUITY SECURITIES

Equity securities, or stocks, are simply evidence of a partial share in the ownership of an enterprise. Thus, individual common stocks are referred to as "shares." Sale of shares is more attractive to the firm than seeking direct investment. Since many shares can be issued for the same enterprise, the firm has access to a much wider pool of capital. This enables the firm to raise larger amounts and so consider larger projects.

Sale of shares is also attractive to management, at least in part, because it has more control over the firm due to the diffusion of ownership. The holder of a share does not have a direct voice in the management of the enterprise, but has an indirect control through the election of the directors, who in turn choose the management of the firm. Voting for directors may be through simple majority voting or through cumulative voting. In the majority system, each investor may cast one vote per position for each share held, and the director receiving more than 50 percent of the votes wins. Under majority voting, a group holding more than 50 percent of the voting stock could lock out minority groups. In the cumulative system, each investor receives one vote per position for each share held, but may cumulate the votes received by casting them all for one candidate. Under cumulative voting, fewer shares are required to guarantee election of a director, so that excluding minority stockholder groups is more difficult. Managements of firms that are takeover targets or are facing challenges from stockholders prefer to be under majority voting. Even under cumulative voting mounting a successful dissident drive faces formidable hurdles, however, since management may dominate the board of directors and controls the assets of the firm. If there is a disagreement with management, the conventional wisdom of Wall Street has been to sell the stock rather than mount a challenge. This conventional wisdom has changed somewhat in recent times because of a willingness of stockholders to take on the role of activists. Also, large positions held by institutions such as mutual funds or pension funds make challenges to management easier to pursue.

The cash flows to an equity investor are not specified in advance. They depend on the success of the enterprise, are uncertain or risky, and are properly described in terms of probability distributions. As part owner of the firm, the owner shares in the success or failure of the firm in two ways. The first way is through returns from capital gains and capital losses arising from increases or decreases in the value of the stock. The second way is through cash flows arising from the distribution of earnings in the form of dividends. The distribution of earnings through dividends is not automatic. Dividends are not an obligation, but instead are declared at the discretion of the board of directors. In practice, dividends are usually not just a function of earnings. Dividends are thought to be a signal to investors as to firm performance. Management prefers to present positive signals, smoothing dividends by avoiding decreases and increasing dividends only if it is likely that the higher level can be maintained. In some cases, firms have raised funds in the capital markets so as to maintain the dividend. An exception is the "extraordinary" dividend, so labeled by management as a sign that the increase is not permanent.

Despite the fact that shares are evidence of part ownership of a firm, common stock has limited liability in bankruptcy. Legally, the firm is considered to be an individual, able to assume its own liabilities separately from the shareholders. As a result, liability is separated from ownership. Limited liability means that the investor is not liable for the debts of the firm, and should the firm fail the investor's loss will be limited to no more than the amount invested. The development of this limited liability form of investment was a major factor in the rise of the corporate form of business, and greatly encourages investment in productive undertakings by individuals because of the risk limitation. In bankruptcy the various claims on the firm follow a well-defined priority, with common stockholders assigned the lowest priority. It is for this reason that the common stockholders are sometimes called the "residual owners" of the firm.

There are other characteristics of equity that are less universal, and there are other exceptions to these general properties of equity securities. Some firms have multiple classes of stock with different voting power and/or share of dividends. Other stock may be restricted as to trading. Common stocks are traded in both organized securities exchanges and over the counter. The size of the underlying firm, and the trading volume of the stock, vary widely. Consequently, the liquidity and the amount of information available on a stock also vary widely.

MONEY MARKET SECURITIES

Money market securities are instruments that are highly marketable, have low credit risk, and are of short maturity, usually one year or less. These securities generally trade on a discount basis, much like a zero coupon bond where the only cash flow is the final repayment of principal. The instruments provide a return by selling at a discount from maturity value. They are usually used by large institutions and mutual funds, and are seldom held by individual investors. Negotiable CDs are large certificates of deposit that can be traded among investors. Banker's acceptances are simply drafts on a bank, to be paid at some future date, which the bank has promised to honor or "accept." These banker's acceptances are traded on a discount basis. Commercial paper is simply an unsecured loan to the issuing firm—they are sometimes called corporate IOUs. Only a small number of firms are able to use this instrument. T-bills, short-term govern securities having original maturities of 91 days or 182 days, are issued weekly, while 52-week maturities are issued monthly. Eurodollars are dollar-denominated deposits at foreign banks or at the foreign branches of American banks. The "Euro" prefix is historic in origin, and the deposits may be in banks worldwide. Both these and the similar eurodollar CDs escape regulation by the U.S. Federal Reserve Board. Repos are the purchase of government securities, with an agreement by the seller to repurchase the securities back at a set higher price—in effect, a very short-term collateralized loan.

DERIVATIVE SECURITIES

Derivatives are securities that provide payoffs according to the values of other assets such as commodities, stock prices, or values of a market index. They are often called "contingent claims" because their value is contingent on or derived from the value of other assets.

OPTIONS.

Options grant the holder the right to decide whether or not a particular action will be taken. A call option grants the right to buy a fixed amount of assets, at a fixed price, for a fixed period, a put option grants the right to sell a fixed amount of an asset, at a fixed price, for a fixed period. The buyer of the option literally buys the right to decide whether or not the trade will be executed (the option exercised): the seller or writer of the option must comply with the decision of the buyer. Most trading is in standardized options traded on an exchange, although individualized contracts are available. Options contracts are available on common stock, commodities, foreign currency, and bonds. Some options are actually written on futures rather than directly on the asset in question, although there is no practical difference. Since delivery of a market index is infeasible, the delivery on index options is made in cash rather than the underlying asset. Options provide tremendous flexibility in creating financial strategies, and are often used to create synthetic securities. Options permit high leverage and may be very speculative, but can also be used to reduce exposure to some types of risk.

FUTURES AND FORWARD CONTRACTS.

A forward contract is simply a commitment to trade a fixed amount at a fixed price at some future date. A futures contract is simply a standardized form of forward contract that is traded on an exchange. The futures contract has the added feature of a clearinghouse that guarantees performance, and the daily marking to market, or payment of gains or losses. Futures may be used by both producers and users of an asset to hedge against price changes, or they can be used as speculative investments.

SWAPS.

A swap is simply an agreement to exchange cash flows. In an interest rate swap, one cash flow is typically at a fixed rate, while the other is at a floating rate. The rates are referenced to a nominal principal in the same currency, but the principal is not exchanged. In a currency swap the cash flows swapped are in different currencies and the rates may be fixed or floating. The principal amount in a currency swap is exchanged at the start and end of the swap. Swaps are relatively new, but have become widely used in corporate risk management to match the characteristics of assets and liabilities.

MUTUAL FUNDS

Mutual funds have become increasingly important as investment vehicles. Mutual funds pool the funds of many investors to invest in stocks, bonds, or other assets. This provides the benefits of professional management and allows wider diversification than can usually be achieved by the individual investor. The fund will often restrict its investment to specified types of securities, such as government bonds, corporate bonds, or large company stocks. Most mutual funds follow a specified investment style or strategy, and a wide spectrum of styles and strategies is available. Styles include growth (attempting to find stocks that will exhibit high future growth), value (attempting to purchase stocks that are undervalued), and index funds that attempt to simply replicate the returns to an index. So-called load funds require a commission at purchase, while no-load funds invest the entire amount. Open-end funds increase or decrease in size as investors buy or redeem shares in the fund, while closed-end funds have a limited number of shares and are publicly traded.

OTHER INSTRUMENTS

There are other instruments that separate ownership from possession and use, and provide limited liability. For various reasons, however, these instruments lack liquidity or other characteristics of securities. An example is the limited partnership, in which only the managing partner exercises management control and assumes full risk. The rest of the partners are called limited partners. The limited partners have no say in the management of the partnership, but in exchange have limited liability. This arrangement has been widely used in real estate investing. The major drawbacks to limited partnerships are the almost total reliance on the ability of the managing partner and the lack of liquidity. Another alternative is the real estate investment trust (REIT). REITs issue publicly traded shares against a portfolio of real estate that is managed by the REIT. This brings the benefits of greater liquidity than limited partnerships.

INVESTMENTS

The process of investing in securities can be visualized in terms of three problems. The first problem is choice—which of the individual assets will be acquired. The second problem is allocation—how the assets will be combined into a portfolio. The final problem is one of timing—how to respond to changing market conditions. This description is helpful in understanding the process, but in practice all three problems are interrelated and must be solved together.

CHOICE.

The problem of choosing among the many securities is called security analysis. The traditional advice of "buy low, sell high" does not answer the question of what is high and what is low—security analysis attempts to answer this question. While three general philosophies can be identified—fundamental analysis, indexing, and technical analysis. Few investors, however, adhere solely to one philosophy. All three are relevant in some way, and there are in reality as many approaches to security analysis as there are security analysts.

FUNDAMENTAL ANALYSIS.

The origin of fundamental analysis is often identified with J. B. Williams's suggestion that securities could be valued as the present value of the anticipated cash flows. This suggestion prompted the application of quantitative economic analysis to securities. Fundamental analysis is based on the belief that it is possible to identify mispriced securities using information about the underlying conditions in the economy, industry, and company—the fundamentals. Analysts using this approach gather and evaluate information about all facets of a firm and its industry. This includes sources such as accounting data, items published in the financial press, information from trade publications, and almost any other source that can be accessed. Professional security analysts usually specialize in one industry or sector of the economy, often maintaining a relationship with the management of the firms under analysis. Using this information and forecasts of economic conditions, fundamental analysts attempt to evaluate the intrinsic value, or the economically rational, correct value for the firm. Similar to bond price quotes in terms of yield, this intrinsic value is often indirectly expressed on the basis of expected return, rather than on dollar price. The return approach is optimal as a technique for comparison across similar firms, where the intent is to identify mispriced assets. Statistical concepts can be applied to provide probabilistic estimates of value or return.

Outside this common philosophy, there is often little in common among the techniques or strategies applied. One common approach is to analyze price\earnings ratios (or P/E ratios). The difficulty of this approach is that it requires specification of the suitable P/E ratio, which is in turn a function of the fundamentals. Somewhat more specific are the discounted cash flow techniques. Essentially, these techniques estimate the future cash flows from the asset, and take the intrinsic value of the asset as the present value of the cash flows. The present value is the amount that, if invested today at the required rate of return on the investment, would just re-create the estimated cash flows. This in turn raises the question of the required rate of return, which is defined as the rate of return on other, similar securities. There are numerous variations of these approaches. Another classification of fundamental analysis is based on management style, the strategy followed in choosing assets. Value managers, for instance, attempt to identify undervalued firms, while growth managers attempt to identify firms that will grow more rapidly than average.

INDEXING.

This approach is identified with the efficient markets hypothesis arising from modern portfolio theory. Indexing is based on the belief that not only can analysts correctly identify mispriced assets, but also they are so efficient at this endeavor that very few stocks will be mispriced, and then only fleetingly. This implies that at any given time the best estimate of the value of an asset is the market price, and the expensive search for mispriced stocks will be unlikely to produce unusually high returns. Under this belief, the optimal course is to purchase a well-diversified portfolio of assets. The approach is called indexing because the portfolio is usually created in such a way as to mimic some market index, such as the Standard & Poor's 500. This approach is most often used for those common stocks that are widely traded.

TECHNICAL ANALYSIS.

Technical analysis has its origins in the Dow theory. It agrees with the belief that stock values depend on the fundamentals. Due to the complexity of the relationships, the constantly changing conditions, and uncertain investor psychology, however, technicians believe that fundamental analysis is futile. Instead, this approach assumes that prices and investor sentiment adjust slowly, producing trends in security prices over time. The emphasis of technical analysis is thus on the detection of trends based on observance of price and trading data. The original theory has over time come to encompass a wide array of possible detection devices.

ALLOCATION

This is the problem of portfolio management. The idea of diversification—holding multiple assets—has always been stressed as correct investment procedure. Historically, however, this was based on an intuitive reasoning such as "Don't put all of your eggs into one basket," and diversification was primarily a matter of the number of different assets to be held. A more exact, quantitative analysis of the nature of diversification was first provided by Harry M. Markowitz in the early 1950s. Markowitz noted that a combination of assets that are not perfectly correlated produce risk and return combinations that are superior to those available from the individual assets. The lower the correlation between the assets, the larger the effect. For example, all other things being equal, the owner of a ski resort would be better off investing in a beach resort than in another ski resort. The reason is the relationship of the pattern of earnings of the investment as compared to the earnings of the ski resort. If the owner acquires another ski resort, in cold years with good snow both would do well; in warm years with poor snow both would do poorly. The result would be a highly variable, risky total earnings stream. If the beach resort is purchased, however, it will do well in warm years and poorly in cold years. This pattern of earnings would balance out the fluctuations of the ski resort earnings, and produce a predictable, less risky total earnings flow.

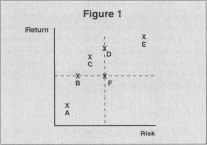

This analysis led to the development of what is called modern portfolio management, and the understanding that asset correlations strongly affect the diversification process. The implication is that the decision to include an asset in a portfolio depends not only on the asset, but also on its relationship with the other assets in the proposed portfolio. Finally, for a given set of assets there are many combinations, and the risk and return of the combinations can vary greatly. The task of the portfolio manager is thus to choose both assets and proportions that will result in a portfolio with a suitable risk and return profile. The task can be visualized in the risk return space of Figure 1. The portfolio manager will avoid a portfolio such as F because portfolio F is dominated by portfolios B, C, and D. Portfolio F is said to be dominated because there are alternatives that are unarguably better. In this case, portfolio B has less risk but provides the same return, portfolio C provides more return for less risk, and portfolio D has more return for the same risk. An economically rational investor would always prefer B, C, or D to F. None of the other portfolios can be said to dominate one another. Portfolio E has higher return than portfolio A, but it also has higher risk. While a young doctor might prefer portfolio E because of its high return, and a widow with several children might prefer portfolio A because of its low risk—this is a

Study of the effect of diversification led to a new way of thinking about risk itself. It became apparent that the risk of an asset had two components. Part of the risk, called diversifiable risk, could be reduced or eliminated through diversification. The reduction of risk through diversification has a natural limit. Although risks that affect individual assets or limited groups of assets can be reduced or eliminated by diversification, risks that affect all assets cannot be diversified. These nondiversifiable risks are those that cause entire capital markets to go through bull and bear phases—i.e., they affect the entire economic system. Another name for the nondiversifiable risk is thus systematic risk, while another name for diversifiable risk is nonsystematic risk. If an investor holds a well-diversified portfolio, it is only the nondiversifiable, systematic risk that is of concern. This systematic risk is measured by the beta of the asset. Modern portfolio theory suggests that the beta of a security is the determinant of the required return on an asset. This analysis, and the use of beta as a risk measure, is most often applied to common stock analysis. The underlying analysis of the nature of diversification, however, is applicable to all investment problems. Finally, this analysis points out a major reason for the growth of international investing. Foreign economies do not move directly with the domestic economy, and provide the opportunity to diversify beyond the domestic systematic risk.

The capital asset pricing model (CAPM) was developed based on the insights of modern portfolio theory, and, unfortunately, modern portfolio theory and the CAPM have become the same in the minds of many investors. This is incorrect—the insights of Markowitz and the resulting importance of diversification are not dependent on the CAPM, and are valid regardless of the validity of the model.

TIMING

Given that the market exhibits bull and bear stages, timers focus on buying and selling according to the market stages. Thus, a timer who anticipates a bull market would increase the proportion of stocks in the portfolio and decrease the amount of cash, and vice versa for a bear market. Cash in this usage is taken to mean money market securities rather than cash itself, since these securities provide return with nearly the liquidity and safety of cash itself. The timer might use either fundamental analysis of economic variables or technical analysis to form expectations. A pure timer would buy or sell an index portfolio, but the strategy is more often combined with fundamental or technical analysis. Timing may also take other forms. A bond portfolio manager might lengthen the maturity of the portfolio if interest rates are expected to decrease, or shorten the maturity if interest rates are expected to increase. Another version of timing is to attempt to buy stocks ahead of the business cycle, or sector rotation.

PROFESSIONAL DESIGNATIONS

There are a number of professional designations in the field of securities analysis. These include:

- Registered representative stockbroker. Brokers are essentially the salespeople of the securities industry. Brokers must successfully complete the Series Seven examination given by the National Association of Security Dealers. The examination covers the basics of securities and markets, and is roughly equivalent in content to a college-level investments course.

- Certified financial planner. This designation is relevant to professionals who provide financial guidance to individuals. This includes brokers, insurance representatives, and others dealing in investment products. The designation is granted by the College of Financial Planners, and requires successful completion of a ten-part examination covering an array of topics relevant to financial planning for individuals. The content would be equivalent to several college level courses.

- Chartered financial analyst. This designation has become widely accepted as a requirement in the investment management industry. The designation is granted by the Institute of Chartered Financial Analysts after successful completion of three six-hour examinations covering various aspects of securities analysis and portfolio management, plus three years of experience in investment decision making. The content is equivalent to a master's degree.

SEE ALSO : Call and Put Options ; Money Market Instruments

[ David E. Upton ]

FURTHER READING:

Bodie, Zvi, Alex Kane, and Alan J. Marcus. Investments. 4th ed. Boston: Irwin/McGraw-Hill, 1999.

Ellis, Charles D. Winning the Loser's Game: Timeless Strategies for Successful Investing. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998.

Fischer, Donald E., and Ronald J. Jordan. Security Analysis and Portfolio Management. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1995.

Malkiel, Burton G. A Random Walk down Wall Street. New York: Norton, 1996.

Reilly, Frank K., and Keith C. Brown. Investment Analysis and Portfolio Management. 5th ed. Fort Worth, TX: Dryden Press, 1997.

Stocks, Bonds, Bills, and Inflation: 1996 Yearbook. Chicago: lbbotson Associates.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: