WORKPLACE VIOLENCE PROGRAM

The 1990s have seen workplace violence (WPV) receive unparalleled attention in the popular press and among safety and health professionals. Much of the reason for this publicity has been the reporting of data by nationally recognized agencies regarding the magnitude of this problem. In 1994 the U.S. Department of Justice warned that the workplace is the "most dangerous place to be in America"; and in 1996 the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) proclaimed homicide the leading cause of occupational injury or death for women, and the second-leading cause (behind motor-vehicle accidents) for men. As a result, companies are now confronting their ethical and legal responsibilities to respond to these increased risk factors with increased awareness of the issue of workplace violence, and decreased tolerance for behaviors that, even as little as a decade ago, may have been considered acceptable. And regardless of the statistical analyses performed on this issue, or the causes assigned to its trends, violence in the workplace is a universal problem, and one that must be addressed proactively by every business, regardless of its commodity, geographical setting, or history of violence. What follows is designed to present a "practical" guide to meeting these demands by generating an effective workplace violence program that documents WPV risk factors, prevention strategies, and response protocols.

KEY STATISTICS

In NIOSH's 1996 Current Intelligence Bulletin (CIB) on violence in the workplace, the institute first pointed out that "sensational" acts of coworker violence (which constituted a relatively small subset of the total picture) were often emphasized by the media to the exclusion of the daily murders and assaults committed by strangers during crimes against particular industries, and that 17 percent of the occupational assaults against women were perpetrated by former husbands or boyfriends.

The CIB then went on to chart the "occupational clustering" associated with workplace violence statistics. According to the report, 56 percent of the fatal assaults, more than 1,000 annually, occurred in the following retail and public order industries (in order of decreasing frequency): taxicabs, liquor stores, gas service stations, security, law enforcement, grocery stores, jewelry stores, hotels/motels, barber shops, and eating establishments. Conversely, accounting for 85 percent of nonfatal workplace assaults were primarily service industries, namely nursing homes, social service organizations, and hospitals, followed (at a distance) by two retail industries, grocery stores and eating establishments.

Additionally, the CIB stated that between 1992 and 1994, between 73 and 82 percent of the circumstances that surrounded workplace homicides were related to robbery or other crimes, followed by business disputes with work associates (9.5 percent), fellow/former employee disputes (5 percent), customer disputes (4.5 percent), police in the line of duty (6.5 percent), security guards in the line of duty (6 percent), and personal disputes with acquaintances (4 percent).

Finally, aside from the unquestionable pain and suffering endured by victims and witnesses of workplace violence, the following figures (provided in 1999 by the National Safe Workplace Institute) tabulate the monetary losses associated with it: A single episode of workplace violence averages $250,000 in lost work time and legal expenses. Productivity decreases as much as 80 percent for up to two weeks after an incident, due to a range of factors including the absence of impacted workers and interruptions due to police investigations, facility damage, the effects of posttraumatic stress syndrome, and time spent debriefing or counseling employees.

CAUSES AND ASSOCIATED PREVENTION

Statistics plainly indicate that the greatest risk of workplace violence is associated with robbery or other crimes. Clearly then, as the general crime rate increases, so too shall crimes perpetrated in the workplace. Consequently, great potential exists for workplace-specific assessment and prevention efforts related to workplace violence from outside perpetrators (e.g., cash-handling policies, physical separation of workers from customers, lighting, security devices, escort services, employee training, and so forth).

Conversely, NIOSH also revealed that over 100 supervisors and coworkers were murdered by fellow employees in 1997, and, according to a Northeastern Facility criminologist who tracks workplace violence nationwide, the number of workers who killed their bosses doubled from 1982 to 1992. Concurrently, shop "culture" has begun to reflect this overall trend. Key departures are: (1) Fighting incidents are more intense than they were in the past, wherein there seems to be an increased willingness to use greater levels of force; (2) the level of discourse is increasingly coarse—harsh words and gross profanity are commonplace; and (3) as a corollary, in order to get attention, vocalized threats have become more specific and more threatening. And while no single cause appears to be forthcoming from experts regarding this trend, several plausible possibilities exist.

One theory suggests that, whereas the workplace was once a source of security, comfort, or even "extended family," many have now have become breeding grounds for anxiety and contentiousness, where layoffs and downsizing are matched in frequency only by hostile takeovers, buyouts, and mergers. Herein, personal integrity, dignity, and humanity have been lost; and with this undercurrent of "impersonalization" may come a growing propensity for acts of violence against the administrative "machine," or against coworkers who have become little more than "inanimate" sources of competition, suspicion, and resentment.

Another theory is that as violence increases, so does the "theatrical" coverage thereof (via the media, television, movies, etc.), thereby desensitizing all of us to its horrors and making it a more conceivable option to those who are already upset or angry at work. And while acts of violence perpetrated by fellow or former employees comprise only 5 percent of total workplace violence incidents, the resulting paranoia, anger, and depression that results from observing peers harming peers is considered to be far more severe in witnesses and survivors than that which results from observing violence perpetrated by strangers. Accordingly, examining possible precursors to this type of violence in the workplace, regardless of how abstract or dynamic the postulates may appear, and using this information as part of a comprehensive workplace violence prevention program, is critical to minimizing these types of incidents.

Every employer's workplace violence program will be distinctly different. This author, however, suggests that each program contain the following four parts and corresponding sections.

PART I—EMPLOYEE PERPETRATORS

Part I of the WPV program should address those components that are dedicated to preventing and responding to violence in the workplace perpetrated by existing or former employees.

BEHAVIORS PROHIBITED IN THE WORKPLACE.

This section of the WPV program should list the company's prohibited behaviors that constitute workplace violence; key examples are below. Note that since regulating language can be a slippery slope, the italicized phrases in the first three prohibitions below may be useful as clarifiers to assist with differentiating between improper, or even offensive, versus truly threatening communications.

- Threats (whether veiled or unveiled, specific or general, serious or facetious) of significant harm to company persons or property, which evoke fear or concern in witnesses or victims

- Communication, verbal or otherwise, intended to raise fear for personal safety

- Obscene communication or racial epithets used as mechanisms of verbal insult or abuse

- Physical assault

- Stalking

- Unauthorized penetration or sabotage of electrical, mechanical, or computer systems, or deliberate damage to facility property

- Unauthorized transporting of weapons onto the premises

Please note that of those prohibitions, all but the first two are already covered by existing policies in nearly every company. Nevertheless, the remaining behaviors are commonly included as "WPV Prohibited Behaviors" in order to illustrate the various types of workplace violence, and thereby integrate the concept of workplace violence, and all that it implies, into the company culture.

Also note that the first two prohibitions will undoubtedly provoke anger, fear, and resentment among employees who will voice grave concerns regarding potential McCarthyism, witch-hunts, First Amendment violations, reckless or malicious reporting, and so forth. A legitimate response to these types of apprehensions is threefold:

- The punitive measures associated with these prohibited behaviors are: (a) decided on a case-by-case basis, (b) follow a multidisciplinary investigation (described in the WPV program), and (c) range from negligible to severe, thereby allowing for a fair and measured response to each prohibited behavior.

- Sexual harassment policies were met with virtually identical concerns, and have been successfully upheld since their inception.

- Statistics bear out the fact that past perpetrators of workplace violence have notoriously threatened to commit their violent crimes (often in startling detail) prior to carrying them out. Thus, until a zero tolerance against threats is invoked, employers are unable to employ an objective and uniform response to what may have otherwise been valid predictors of violence, and employees have no means to report threatening behavior without the risk of appearing paranoid or oversensitive. Moreover, the repercussions of ignoring this type of historical evidence, and thereby risking serious injury or death to employees, must necessarily outweigh the (as-yet-unsubstantiated) concerns voiced by objectors to the policies.

WPV OBLIGATIONS—EMPLOYER AND EMPLOYEE.

This section of the WPV program should identify what the company considers to be the employer's and the employees' obligations related to preventing and responding to WPV.

It is advisable for employers to have in place the following:

- Preventive prehire and layoff practices

- A statement of zero tolerance against violent threats and behaviors in the workplace

- Policies and procedures presenting consequences that can result when WPV occurs

- A policy regarding employee responsibility to report violent threats or behaviors and procedures for how to do so

- A TMT that will investigate all reports of violent threats or behavior

- A description of possible intervention strategies and who will perform follow-up

- Training programs for employees and their supervisors that include warning signs of potential violence and guidelines for de-escalating potentially violent behavior

- A trauma plan that addresses emergency measures to be taken during a WPV incident, including an emergency signal or code to be used.

On the other hand, key employee obligations are to:

- Understand and agree to the terms and conditions of this policy/program

- Familiarize themselves with this WPV program and/or attend WPV awareness training

- Understand and accept that a consequence of the facility's duty to provide a safer working environment is that actions of individuals are regulated in a more conservative manner

- Refrain from participating in any of the prohibited behaviors described in this program

- Report persons engaging in any of the prohibited behaviors identified in this program, or report any behavior that constitutes threats or potential/actual acts of violence that they have witnessed, received, or discovered through a third party.

GENERAL RISK ASSESSMENT AND ASSOCIATED PREVENTION STRATEGIES.

This section of the WPV program should document the company's area(s) of greatest risk for employee violence (without regard to particular incidents or individuals), and briefly describe general mechanisms in place for lowering these risks.

General areas of high risk often include: (1) poorly executed hiring practices; (2) poorly conceived firing practices; and (3) discrete areas (e.g., offices, departments, divisions) that employ especially disgruntled employees and/or present a history of workplace violence. Accordingly, this section may identify prehire practices for supervisors that include explicit screening for prior violent acts/crimes or disproportionate

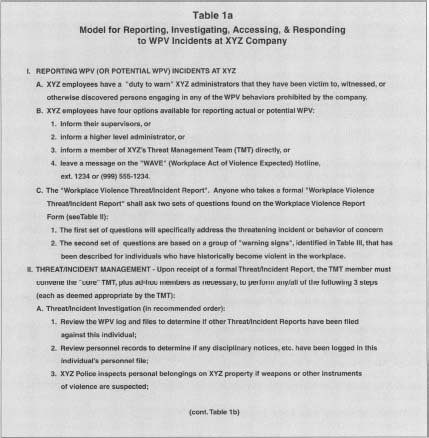

Model for Reporting, Investigating, Accessing, & Responding

to WPV Incidents at XYZ Company

|

Model for Reporting, Investigating, Accessing, & Responding

to WPV Incidents at XYZ Company

|

workplace anger. Likewise, this section could provide various mechanisms for notifying subordinates of layoffs that are less likely to result in violence. Finally, some companies conduct cultural assessments to measure their employees' attitudes and beliefs in order to isolate (and address) those locales of higher risk; a description of the nature and frequency of these assessments can be described in this section.

PROCEDURES FOR REPORTING, INVESTIGATING, ASSESSING, AND RESPONDING TO INCIDENTS.

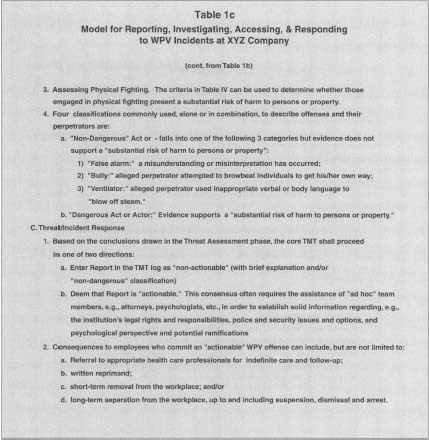

This section of the WPV program should provide the explicit procedures for reporting, investigating, assessing, and responding to WPV incidents. Obviously, this section will vary the most significantly from facility to facility. Nevertheless, Table I (and associated Tables 2-4) constitute a detailed example of this section in order to accomplish two goals: (1) streamline the various guidelines and recommendations of a broad assortment of WPV research/literature into a practical process; and (2) provide a working model of how an actual WPV investigation might be approached.

For purposes of drafting this section of the WPV program, it may serve the company to include a great deal of step-by-step detail, much like writing an "administrative recipe" (see Table 1). And, while this approach may superficially appear to offer inadequate levels of administrative flexibility, it actually offers each of the TMT members more protection by limiting independent judgments and decisions (based on a personal history with the employee, a Polyanna nature, and so forth), which may later prove disastrously erroneous. And, as the model in Table I shows, any and all steps of the threat/incident management process may be eliminated by consensus (and documentation)

Model for Reporting, Investigating, Accessing, & Responding

to WPV Incidents at XYZ Company

|

of the core TMT. Overall then, this approach inherently affords the company better and more uniform risk management.

The company may also want to include in this section frequently asked questions regarding the WPV reporting process. The following are two of the most common questions posed by individuals who are considering filing WPV threat/incident reports. Legitimate responses follow.

Q. If I file a report, will I be notified of the precise outcome of the TMT's investigation?

A. The TMT shall not generally divulge to any reporting employees the explicit course of action taken in response to a threat/incident report; as a result, reporting employees are strongly encouraged to contact the TMT immediately if threatening or violent behavior is repeated at any time following the initial report.

Q. If I file a report, will I be guaranteed absolute anonymity?

A. The TMT will handle all matters brought to its attention with due regard for your confidentiality, privacy rights, and concerns for safety, but if you disclose your identify to a TMT member, that member cannot guarantee absolute or permanent anonymity. An anonymous WPV reporting hotline, however, has been set up for individuals who desire anonymity.

TRAINING.

In this section, the WPV program should list, at a minimum, the following:

-

The primary topics that will be covered in this training. Key topics are

as follows:

- How to recognize the danger signs of potential workplace violence

- How to file a workplace violence report

- How to diffuse a potentially violent individual

- How often the training is held

- Who will present the training

- Who is required to attend

- Who is encouraged to attend

- How to obtain additional copies of the written WPV program.

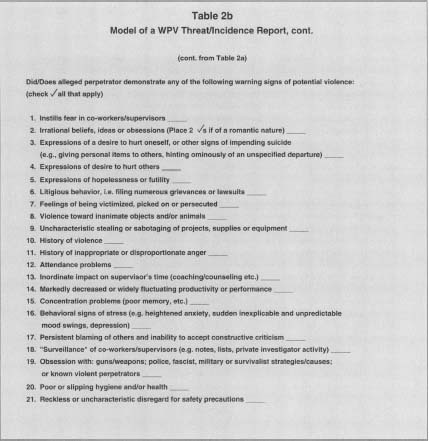

Model of a WPV Threat/Incidence Report

|

COMPOSITION OF THE FACILITY'S THREAT MANAGEMENT TEAM.

In this section, the WPV program should briefly reiterate the function and purpose of the TMT, and then list the names, positions, and complete contact information for every individual on the team.

Generally, a TMT will be comprised of a core team, supplemented by ad hoc team members, who are brought in on an as-needed basis. The core team would include a representative from the risk management department, a representative from the occupational safety department, a representative from the police department, and representative(s) from the human relations department (including a representative from bargaining, as well as the employee assistance program, whenever possible). Ad hoc team members include a representative from the general counsel's office, psychologist(s) and/or psychiatrist(s), a representative from media/public relations, and outside (the company) experts as necessary.

PART II—NONEMPLOYEE PERPETRATORS

Part II of the WPV program should address those components that are dedicated to preventing and responding

Model of a WPV Threat/Incidence Report, cont.

| Did/Does alleged perpetrator demonstrate any of the following warning signs of potential violence: (check/all that apply) |

|

to violence in the workplace perpetrated by individuals never employed by the company.

GENERAL RISK ASSESSMENT AND ASSOCIATED PREVENTION STRATEGIES.

This section of the WPV program should document the company's area(s) of greatest risk for nonemployee workplace violence, and briefly describe the general mechanisms in place for lowering these risks.

General areas of high risk include work sites that: (1) are primarily staffed by women, which introduces a higher risk of domestic violence; (2) are located in areas where one or more crimes are particularly common (e.g., robbery, gang-related crimes, rape, arson); (3) have a history of workplace violence; (4) handle cash or other valuable commodities; (5) have individuals who work alone; and (6) are removed (indefinitely or intermittently) from the general population. Accordingly, this section may identify any number of general preventive strategies, such as badge-only entry, security cameras, enhanced night lighting, domestic violence education and counseling, cash-handling policies, physical separation of workers from customers, escort services, and so forth.

TRAINING.

This section of the WPV program should list, at a minimum, the following:

-

The primary topics that will be covered in this training. Key topics are

as follows:

- How to recognize the danger signs of potential workplace violence

- How to diffuse a potentially violent individual

- The facility's emergency signal or code word

- How and why to best utilize the general WPV prevention strategies and equipment provided by the company

- How often the training is held

- Who will present the training

- Who is required to attend

- Who is encouraged to attend

- How to obtain additional copies of the written WPV program

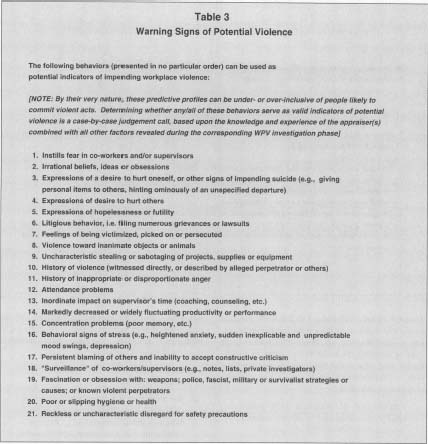

Warning Signs of Potential Violence

| The following behaviors (presented in no particular order) can be used as potential indicators of impending workplace violence: |

| [NOTE: By their very nature, these predictive profiles can be under- or over-inclusive of people likely to commit violent acts. Determining whether any/all of these behaviors serve as valid indicators of potential violence is a case-by-case judgement call, based upon the knowledge and experience of the appraiser(s) combined with all other factors revealed during the corresponding WPV investigation phase] |

|

RESPONSE TO POTENTIAL OR ACTUAL INCIDENTS.

This section of the WPV program should present mechanisms for summoning emergency assistance in the wake of a potential or actual WPV incident. It would include information about any emergency signals or code words that are to be used under these circumstances. It would further differentiate, if necessary, the discrete response measures for each type of perpetrator (e.g., an enrolled student versus a "trespasser" on a college campus, a patient versus a visitor in a hospital).

OBTAINING PERSONAL PROTECTION ORDERS.

This section of the WPV program should describe in detail the following:

- Purpose and function of a personal protection order (PPO)

- How to obtain a PPO (and what part the employer can play in this process)

- The legal criteria considered when issuing a PPO

- Who at the facility can assist with questions regarding PPOs

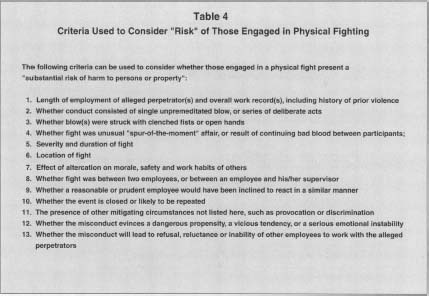

Criteria Used to Consider "Risk" of Those Engaged in Physical Fighting

| The following criteria can be used to consider whether those engaged in a physical fight present a "substantial risk of harm to persons or property": |

|

TRAUMA PLAN.

This section of the WPV program should either present all information pertaining to critical incident response, or should refer readers to an existing company document that provides said information (e.g., the company's "emergency response plan" or "crisis management plan"). Key examples of topics to include are:

- Coordination of personnel from police, emergency response, medical, security, evacuation, and buildings and grounds

- Management of key communications with employees, media, customers, victims' families, counselors, etc.

POSTTRAUMA RESPONSE.

This section of the WPV program should present the company's policy and procedures following a violent incident (including resources and funding). Key examples of topics to include are:

- Crisis intervention and debriefing of victims and witnesses within 24 hours of the incident

- Treatment of posttraumatic stress syndrome

- Grief management services

WPV PROGRAM APPENDICES

FORMAL POLICY REGARDING WPV.

Given the controversial nature of any WPV policy, it must first be reviewed by the facility's general counsel, and subsequently approved, endorsed, and delivered from the top down, i.e., by the company's president, cabinet, and/or board of directors; otherwise effective implementation is unrealistic. This policy should include at least the following elements:

- Prohibited behaviors that constitute violence in the workplace.

- The steps that will be followed to address employees who allegedly engage in one or more prohibited behaviors (e.g., incident investigation, risk assessment, and response).

- The range of punitive responses that may be employed in response to acts of workplace violence (e.g., referral to appropriate health care, written reprimand, short-term removal from the workplace, long-term separation from the workplace, dismissal).

- The penalty for making false or misleading WPV reports.

- The penalty for retaliating against those who have made good-faith WPV reports.

COPY OF WORKPLACE VIOLENCE THREAT/INCIDENT REPORT.

Employees should be able to examine a WPV threat/incident report prior to making the decision to file a report. A model of a WPV threat/incident report is provided in Table 2.

INSTRUCTIONS FOR ACCESSING/USING THE WPV "HOT LINE"

Assuming that the facility has set up a "hot line" for reporting potential or actual WPV incidents the following information should be provided regarding its access and use:

- The telephone number to dial from inside or outside the facility

- What the caller can expect to hear on the recorded message, and what information he/she is expected to provide at the tone

- A statement about caller anonymity

CONCLUSION

The days of operating without a workplace violence program are over. Every company's program and associated policies and procedures will undoubtedly be carefully scrutinized by myriad governing agencies, not to mention hungry attorneys, after a violent incident. Furthermore, employers are obligated under the Occupational Safety and Health Act's "General Duty Clause" to furnish a workplace "free from recognized physical harm." According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), this section of the act may be invoked where the employer fails to keep the workplace free from a hazard to which its employees were exposed, the hazard was recognized, the hazard caused or was likely to cause death or serious physical harm to workers, and a feasible or useful method for correcting the hazard existed. More specifically, on January 13, 1994, the head of OSHA announced a goal to address workplace violence via this section of the act by citing employers who do not adequately protect their employees from workplace violence. Consequently, OSHA has begun citing workplaces where one or more of the following is not present (regardless of whether histories of violence exist at those workplaces): (1) a workplace violence policy/program, (2) mandatory training to staff in the key components of that program, and (3) documented enforcement of the WPV policies therein.

Admittedly, the process of drafting a practical and useful WPV program is arduous and controversial. The risks associated with not doing so, however, clearly imply a social, moral, legal, and economic irresponsibility that cannot be overlooked.

[ Rikki B. Schwartz ]

FURTHER READING:

Baron, S. Anthony. Violence in the Workplace: A Prevention and Management Guide for Businesses. Ventura, CA: Pathfinder Publishing of California, 1993.

——, and Eugene D. Wheeler. Violence in Our Schools, Hospitals, and Public Places. Ventura, CA: Pathfinder Publishing of California, 1994.

Blythe, Bruce, and Rick Gardner. "Eye on Workplace Violence." Risk Management, April 1999, 43.

Dobry, Stanley T. "Legal Aspects of Workplace Violence." 21st Annual Labor and Employment Law Seminar, sponsored by the Institute of Continuing Legal Education. 26 December 1996. 13: 21-77.

Doering, Barbara W. "Violence and Fear of Violence in the Workplace." Labor Arbitration Institute, 1996, 103.

Nuyen, Donna R. "Resolving Violence in the Workplace: A Management Perspective." Fundamentals of Michigan Employment Law Workshop, sponsored by the Institute of Continuing Legal Education. 21 July 1995. 3: 3-24.

U.S. Department of Justice. Office of Justice Programs. "Workplace Violence, 1992-1996." National Crime Victimization Survey. Washington: GPO, 1998. Available from www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs .

U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Division of Safety Research. Current Intelligence Bulletin 57: Violence in the Workplace/Risk Factors and Prevention Strategies. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 96-100. Cincinnati: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, 1996. Available from www.cdc.gov/niosh/violcont.html .