SIC 0722

CROP HARVESTING, PRIMARILY BY MACHINE

This industry encompasses establishments primarily engaged in mechanical harvesting, picking and combining of crops, and related activities, using machinery provided by the service firm. Crops undergoing mechanical harvesting include berries, fruit, cotton, grain, nuts, sugar beets, sugarcane, and vegetables. Companies that provide threshing, combining, silo filling, and hay mowing and baling services are also included in this classification. Farm labor contractors providing personnel for manual harvesting are classified in SIC 0761: Farm Labor Contractors and Crew Leaders.

NAICS Code(s)

115113 (Crop Harvesting, Primarily by Machine)

Industry Snapshot

This industry is comparatively small, and it is dominated by family-owned companies. Crop harvesters, both manual and mechanical, are directly reliant on the economic fortunes of the American farming community, the sole client of the harvesters.

Organization and Structure

American agribusiness is a huge, diversified industry and encompasses several specialized sectors. Besides the farmer (also called the grower), who manages the land and cultivates the crops, there are industries based around companies that harvest, process, distribute, and transport farm products and farm supplies. There are also industries based around companies that supply materials and services to the farmer. Contract or custom harvesters are part of the former group.

It is increasingly common for farmers to enter into contracts to sell their produce before it has matured. Contract farming is an arrangement with a buyer, such as a food processor or marketer, to sell and ship the produce to the buyer upon harvesting. The custom harvesting company may be an intermediary part of this arrangement. If the company has been contracted to do the harvesting, it may also make the arrangements for selling and shipping the product to the buyer on the grower's behalf.

The farmer agrees to a price at the time of the contract. This arrangement can benefit either the grower or the harvester/buyer, depending upon supply and demand of the particular type of crop at harvest time. If there is a nationwide bumper crop of green beans, and the farmer is selling green beans, the farmer may get a higher price for the crops with a contract than if he or she waited for the harvest and bid with many other farmers waiting to sell their beans. If crop production is low, creating high demand, the buyer comes out ahead because the farmer could have sold for a higher price, had he or she known there would be a smaller supply. The custom harvester, having agreed to buy a crop at a certain price before it has matured, is subject to similar losses or gains.

The custom harvester contracts production with the food processor. The contract will specify the delivery of tons of produce per day, which will fluctuate according to weather conditions or other variables. The custom harvester also contracts with the grower to produce the crop. The harvester begins working with the grower when it is time to plant the crop. The harvester's field representative works with the grower to coordinate various facets of the planting process. For the harvester, this is to set standards for the crop and ensure quality control. The field representative delivers the seed and develops the timing for planting, fertilizing, and harvesting the crop. The grower pays for the seed, because it is held against his or her account when the grower is paid for the harvested crop.

Large harvesters generally have a variety of equipment that enables them to harvest the crop of their choice. They harvest with their own machinery, load the produce onto their own semi-tractor-trailers, and ship it to the processor. Large contract harvesters also have trucking and communications systems in place. These systems are crucial because, in order to fulfill the contract with the processor, the harvesting company may have to send trucks, equipment, and harvesting crews to different states for harvesting jobs. They go wherever they need to fill the packing window. Weather can determine the order in which the harvester chooses the farms. Timing is crucial, because each crop matures at a different rate and must be harvested at its peak. Increasingly, harvesting companies use computers to track the planting dates, varieties, and pesticides (herbicides, fungicides, insecticides) used by different growers. The time frame for a harvesting job can range from a few days to two weeks, depending upon crop, terrain, and size of acreage.

Mechanically-Harvested Crops. In deciding whether to harvest mechanically or manually, farmers must consider what type of crop and plant is being harvested. Grain crops are harvested mechanically. In the case of vegetable crops, however, they may be harvested mechanically if a hardy variety or if not intended for the fresh market. Many fruits and vegetables, especially citrus fruits, are harvested almost exclusively by hand because they must arrive on the fresh market in perfect condition, and mechanical harvesting can scratch or bruise produce. Damage is a major concern of reap harvesting. Damage is usually minimal if the harvesting equipment is kept clean and adjusted correctly for the crop. Even with hand harvesting, however, machinery, such as conveyor belts, will likely be used to transport the fruit from the field, to cool it and perhaps wrap it. Farmers may also choose to harvest by hand if they have secured a high price for their crop and can afford manual labor. They may combine their options within the same crop, picking large, mature vegetables first by hand for the fresh market and then bringing in machinery to harvest smaller vegetables for sale to a processor.

Time is also a major consideration. If farmers need to harvest quickly, they will need to harvest mechanically. In deciding whether to harvest by themselves or to contract with a custom harvester, farmers have another set of factors to consider. If the farmers have a lot of acreage, they may own a combine harvester. Often, they will make arrangements to harvest the crops of their neighbors as well. If the farmers grow grain and do not have enough acreage to justify making the capital investment in a combine harvester (about $120,000), they will need the services of a contract harvester.

Convenience and assistance may be a factor as well. Farmers may find it easier to have the input of the custom harvester in determining crop planting, timing, harvesting, and sale issues. Even if the farmers do own a combine harvester, they may still contract a custom harvester. One reason is that the window of opportunity for harvesting is small. Farmers may need to get grain out of the field immediately or risk losses because of bad weather, for example. If they don't have the capacity to do the job themselves, they may seek help from a custom harvester.

Equipment. The combine harvester used for grains tends to be different from the one used for vegetables, although the manufacturers strive to make the machines more interchangeable through modifications. Harvesting machinery is generally classified by crop. A harvester must be adjusted to harvest a specific crop and to keep trash out of the load. A grain harvester is called a combine harvester because it cuts, threshes, and cleans grain in one operation. Corn is harvested by mechanical pickers that snap the ears from the stalk so that only the cobs are harvested. Stripper-type cotton harvesters strip the entire plant of both open and unopened bolls. Hay and forage machines include mowers, crushers, windrowers, field choppers, balers, and grinders.

Root crops such as potatoes are harvested with diggers, which often pull up rocks and unwanted vegetation with the potatoes. Some machines can sort this trash out, while other machines carry people who sort it by hand. Sugar-beet harvesters lift the whole root from the ground, clean it, and deliver it to a bin. Vegetable crops such as broccoli, asparagus, celery, lettuce, and cabbage are still harvested largely by hand.

For the fresh market, some vegetables and nearly all fruits are still harvested by hand. For processing, drying, and occasionally for fresh market, mechanical tree and bush shakers with catching belts, bins, pallets, and electric lifts reduce harvesting and handling labor.

Background and Development

Some custom harvesters are family-run outfits that started as growers, purchased expensive harvesting equipment, and entered into agreements with other local farmers to harvest their crops. They are likely to grow crops and maintain livestock in addition to their harvesting operations. Others are large and sophisticated operations that coordinate production with the grower from planting to sale and delivery.

The history of mechanical harvesting itself dates back to Cyrus McCormick's marketing of the mechanical reaper in the early 1840s. The reaper could harvest grains only; mechanical harvesters for root and vegetable crops weren't invented until the 1930s. McCormick's invention was an important part of the agricultural revolution that began in the eighteenth century.

The agricultural revolution dramatically increased a farmer's ability to produce crops. The technique of crop rotation allowed farm land to be used continually. Machinery allowed ever larger areas to be worked, and farmers increased their acreage. When mechanical harvesters and other devices were created to do formerly manual labor, production increased to a level that surpassed national consumption. The McCormick reaper permitted the cultivation of the vast Midwestern plains states.

The proportion of human labor used in the production of farm goods dropped by measurable degrees as a result of farming advances, while capital spending on feed, machinery, fertilizer, and other farming staples increased dramatically.

Farmers now rely heavily on specialized technology to sustain and increase production. Farmers are also highly dependent on outside sources for their equipment and services, such as custom harvesting. Because of these specialized interrelationships, farmers and the businesses that support them have also necessarily become increasingly sophisticated in their cash management techniques.

In the late 1990s efforts to develop new machines to facilitate the labor-intensive harvesting of crops intensified. In Florida, for example, providers of citrus for the production of juice faced labor shortages, and exploration

of mechanical harvesting options became necessary. The most promising type of mechanical harvesting system appeared to be the "continuous canopy shake and catch," which resulted in as much as a 75 percent decrease in harvesting costs. These systems were appropriate only for fruit destined for juice production, as fruit for fresh consumption would suffer from too much damage from the machinery.

Current Conditions

Because this industry sustains itself by providing services to farmers, it is affected by many of the same economic, climactic, and industrial conditions that affect farmers. The early 2000s saw a slight improvement in the American farm economy, after three years of decline in the late 1990s. Net farm cash income was more consistent and higher than in previous years. After falling from $207 billion in 1997 to $187 billion in 1999, U.S. farm cash receipts climbed to $193 billion in 2000 and to $202 billion in 2001. Farmers who stored grain were able to take extra advantage of relatively high commodity prices. After grain reserves had reached historically low levels in 1993-94, producers had expanded their crops to keep up with increased national and international demand.

In 2003 about 10.3 billion bushels of corn were produced, the highest on record and a significant increase over the 2002 crop of 9.01 billion bushels. Wheat production fluctuated dramatically in the early 2000s as well. After falling to 1.9 billion bushels in 2001 and to 1.6 billion bushels in 2002, wheat production rebounded to 2.3 billion bushels in 2003. Soybean production dropped 12 percent in 2003, falling to 2.42 billion bushes, its lowest level since 1993.

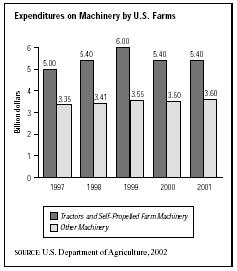

In 2001 farmers spent a total of $25.4 billion on farm services, up from $23.5 billion in 1996. This figure covered all farm services, not only expenditures for the mechanical harvesting of crops. Also in 2001, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, expenditures on tractors and self-propelled farm machinery remained steady at $5.4 billion, while spending on other farm machinery increased from $3.5 billion to $3.6 billion. These figures suggested continued use of mechanical harvesting equipment on U.S. farms.

Industry Leaders

Among the leaders in the mechanical harvesting services industry in the early 2000s were Noblesse Oblige Inc. of Seeley, California; Apio of Guadalupe, California; and Fresh Western Marketing of Salinas, California. Other companies engaged in providing mechanical harvesting services were geographically clustered in agricultural regions in such states as Texas, Kansas, Oklahoma, Indiana, Wisconsin, Florida, and California.

Further Reading

U.S. Department of Agriculture. Track Records of U.S. Crop Production. Washington, DC: 2003. Available from http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/data-sets/crops/96120/track03b.htm .

U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. "Farm Production Expenses." 2002. Available from http://www.usda.gov/nass/pubs/stathigh/2003/tables/economics.htm .

U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. "U.S. Farm Cash Receipts." 2002. Available from http://www.usda.gov/nass/pubs/stathigh/2003/tables/economics.htm .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: