SIC 0751

LIVESTOCK SERVICES, EXCEPT VETERINARY

This classification covers establishments primarily engaged in performing services, except veterinary, for cattle, hogs, sheep, goats, and poultry. Dairy herd improvement associations are also included in this industry. Establishments primarily engaged in the fattening of

cattle are classified in SIC 0211: Beef Cattle Feedlots. Establishments engaged in incidental feeding of livestock, often during periods of transportation, as a part of holding them in stockyards for periods of less than 30 days are classified in SIC 4789: Transportation Services, Not Elsewhere Classified. Establishments that perform services, except those in the realm of veterinary services, for animals not classified as livestock are classified in SIC 0752: Animal Specialty Services, Except Veterinary.

NAICS Code(s)

311611 (Animal (except Poultry) Slaughtering)

115210 (Support Activities for Animal Production)

Industry Snapshot

The raising of cattle, sheep, hogs, goats, and poultry requires several specialized husbandry skills, many of which are performed by members of the livestock service industry. These services range from artificial insemination to pedigree record keeping to sheep dipping and shearing.

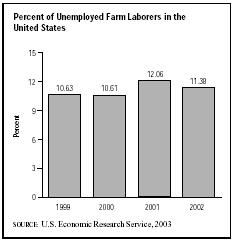

Labor use on American farms and ranches has changed dramatically since World War II. In 1950 nearly 10 million workers were employed on farms and ranches, but by 1969 this figure had been reduced to 3.1 million. In subsequent decades, this number continued to drop and held at less than 1 million in the early 2000s. This decrease was the result of the trend toward fewer and larger agricultural enterprises and the increasing use of technological innovation. One result of increasing concentration and the development of very large poultry and livestock feeding enterprises has been the switch from family labor to the increased use of temporary workers. In the early 2000s, roughly 20 percent of all farms relied on contract labor, a sizable increase from 1980 when only about 2 percent did. Another result has been higher than average unemployment rates among farm laborers. In 2002 roughly 11 percent of the hired farm labor force was unemployed, compared to an average of roughly 6 percent for the U.S. labor force as a whole.

Establishments in this industry provide a range of livestock maintenance services. In 2003 two of the leading livestock service providers in the United States were ABS Global, Inc. and Pig Improvement Company, Inc. A subsidiary of Genus plc, ABS extended its international reach in 2003 with the purchase of RAB Australia Pty. Ltd., the largest private cattle insemination operation in Australia. Also that year, Pig Improvement and Birchwood Genetics, based in Ohio, entered into an agreement designed to boost artificial insemination capacity for both firms.

Organization and Structure

Breed Associations. These organizations perform many services, including tracking of pedigree information and performance records. Typically, a breeder of purebred livestock registers the offspring of his herd or flock shortly after they are born. To be registered in the national herd book these animals must be of purebred parentage, meaning that both sire and dam were previously recorded with the breed registry. Breed associations keep these records and in so doing maintain the purity of the breed. Most breed associations have a paid field staff whose job it is to assist the purebred breeders in filling out the paper work, designing breeding programs, and even aiding in the selection and procurement of seed stock.

Increasingly, it has fallen to the breed associations to also keep performance data on livestock animals. Breeders send in such data as birth weights, weaning weight information, or—in the case of dairy cows—milk production figures. The breed association then gathers up all the data from the participating breeders and publishes this information in the form of sire summaries and "expected progeny differences." This computer-generated data aids purebred and commercial breeders in selecting those animals with the highest production traits. The role of the various breed associations is rapidly expanding, primarily because of their large databases of performance information. This data has become increasingly valuable as the animal industries turn to what is known as "value-based marketing." Purchasers of livestock—feedlots, dairies, piggeries, and processors—demand to know the performance ability and meat quality of the animals before they purchase them.

Examples of breed associations in the beef industry include The American Hereford Association and the American Angus Association. The Holstein Association keeps pedigrees and production information for Breeders of registered Holstein dairy animals. There are more than a dozen sheep registries, including the American Hampshire Sheep Association, the American Suffolk Sheep Society, and the National Suffolk Sheep Association.

Artificial Breeding Services. Another service industry common to most domesticated livestock establishments is the artificial insemination stud and breeding service. Artificial insemination is widely used in dairy cattle and poultry and to a lesser extent with beef cattle and hogs. Those employed in the breeding industry purchase or lease superior animals, house them at their facilities, collect their semen regularly, merchandise the semen, and ship it in frozen nitrogen to their livestock-raising customers. Recent technological innovation is making it possible to sex the semen so that a producer can determine the gender of the resulting offspring.

The concept behind artificial insemination is the same for all species; however, the procedures vary from animal to animal. When superior producing male animals are identified their semen is drawn and extended. Extension is the process whereby 10 cubic centimeters of semen is extended to provide 100 or even 200 doses. For cattle, the semen is frozen and then sold by the straw or ampule to other breeders who in this manner can use the best genetics available. In the case of dairy animals, it might be possible for a superior dairy bull to produce a million offspring through insemination techniques. Without the use of this technology, the bull's number of offspring and his contribution to the breed would be significantly reduced. But for hogs, the semen must be fresh in order to work. Hence, artificial insemination is more difficult for pigs and has not been as successful. Operations offering this service try to accommodate hog farmers within a 50 mile radius of the operation's headquarters. Computers and refrigerated trucks play a crucial role in the tracking and expeditious delivery of the hog semen.

In the case of artificial insemination for poultry, the inseminator collects semen from roosters and, using a microscope, records the motility and morphology of the semen. A specified amount is then placed into a syringe-like inseminating gun and the semen is injected into the oviduct of the hen or through a tiny hole in the egg shell. The use of artificial insemination in poultry has expanded such that it accounts for nearly 99 percent of all new birds in the turkey production industry. This production route has resulted in turkeys with much more meat than the average bird of a few years ago. Typical turkeys now have so much meat on their breasts that they are unable to mate in the usual manner.

Technological innovation and research has led to another breakthrough in reproductive physiology—embryo transfer. Just as it is desirable to increase the offspring from a superior male, so too is it advantageous to increase the number of offspring from a superior female. By taking the eggs from an animal's ovary, implanting them in a petri dish with genetically superior semen, and then implanting them back into a recipient female, the breeding potential of superior females is being expanded. The recipient female actually gives birth to an animal that has none of her genes. These tasks are performed by a growing number of businesses located throughout the country.

Central Test Stations. Testing stations are also common to several species of livestock. Sometimes associated with a university, these test stations can also be individually owned. It is the purpose of a test station to feed, weigh, measure, and record the performance of bulls, rams, and boars. The data is used to compare consignments from several breeders and in many cases the animals are then sold at auction to go into other seed stock operations. Through the use of centralized testing stations the universities and land grant colleges have played a vital role in identifying animals with superior genetics.

Fitting Services. The showing of hogs, sheep, goats, and cattle at livestock fairs and expositions is often left to professional fitters. Animals entered in these contests are groomed, fed, and hauled from one fair to another, often by fitting services that perform these services either for a flat fee or a percentage of the prize money. In many instances one fitter's string of show animals might include animals from several different breeders.

Custom Slaughtering. The people who perform these services are few and far between. It is illegal to raise an animal, have it custom slaughtered, and then sell that animal's carcass or meat to another individual without having it inspected by a government inspector. Therefore, most custom slaughtering is done for ranchers or raisers of livestock on animals they have raised for their own family's consumption.

Specialized Species Services. In many instances the services required by one animal species are unique to that animal. Specialized services regarding sheep include sheep herders, sheep shearers (usually contract labor, with payment either by the head or for a flat fee. This is difficult, highly-skilled work), fleece tiers, lambers (individuals hired during birthing season to aid the ewes in delivery), and trappers. The trapper hunts, kills and traps predatory animals that are killing lambs and sheep.

The Animal Damage Control program of the USDA provides direct assistance to private individuals to help protect their animals from injury and damage caused by wild animals. Under the Animal Damage Control Act of 1931 there are state and federal funds available to help pay for the services of a trapper. In the past trappers used to work for a bounty, but most are now independent contractors since most bounties have been discontinued. The trapper's practices and methods are much more regulated and controlled than in the past.

Specialist positions in the poultry service area include caponizers, who castrate cockerels (very young male chickens) to prevent the development of secondary sex characteristics; debeakers; poultry vaccinators; and chick graders and sexers. In the area of dairy cattle, while most work on the modern day dairy is performed by the facility's employees, milk testing is one task that is "farmed" out. The milk tester or sampler can either work for a dairy herd improvement association, a breed association, or an independent service. It is the tester's job to collect milk samples from dairies, processing plants or tank trucks for lab analysis.

Further Reading

"ABS Global Acquires Australia RAB." Feedstuffs, 3 March 2003.

U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Farm Labor: Employment Characteristics of Hired Farmworkers, Washington, DC: 13 November 2003. Available from http://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/Farmlabor/Employment/ .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: