SIC 0161

VEGETABLES AND MELONS

This entry includes establishments primarily engaged in the production of vegetables and melons in the open, including asparagus, beans, broccoli, cabbage, cantaloupe, cauliflower, celery, sweet corn, cucumber, green peas, lettuce, onions, peppers, squash, and tomatoes.

NAICS Code(s)

111219 (Other Vegetable (except Potato) and Melon Farming)

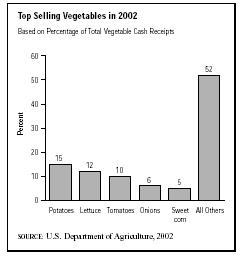

Of the produce included in this category, tomatoes, onions, and iceberg lettuce led per capita consumption, as well as vegetable cash receipts, in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Vegetables and fruits (truck farm products) are the second largest food group in the United States by volume and consumption, behind milk and dairy products. California, Florida, Texas, Arizona, and New York are the largest truck farming states. Produce is sold directly to processors, wholesalers, retailers, or consumers by truck farmers. Large truck farms usually specialize in one or two crops for shipment to the rest of the country, while smaller farms may grow a large variety for sale at local farmers' markets, stands, and stores. Smaller farms may also market their produce together through a cooperative in order to negotiate better prices.

Truck farms developed as people moved to cities and could no longer grow their own produce. With the building of railroads and highways, and the development of

refrigerated transportation, truck farmers were able to ship their produce farther. Trucks and trains could carry out-of-season produce to the north from truck farms in the south.

Truck farmers in the United States have had to contend with periodic scares regarding the safety of fruits and vegetables. Various consumer and environmental groups claimed that too many pesticides, fungicides, and other chemicals were used on crops. Government agencies and industry groups, however, have insisted the food supply is safe and any chemical residue is well within government limits. Domestic growers have also defended their produce from fears about contaminated imports. Because produce is integrated into stores, usually without differentiation between foreign and domestic products, domestic growers have been concerned their produce would be affected by any suspicion about the quality of the imported goods.

In 1992 the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued new rules requiring employers to protect farm workers from pesticide poisoning, although these national rules were still not as strict as those in place in California. The new rules barred employees from going back into freshly sprayed fields, with the quarantine periods ranging from 12 hours to three days, depending upon the chemical used. After pesticide concern continued to escalate, President Clinton signed a bill in 1996 that required the EPA to establish safe levels of tolerance for pesticide residue on both fresh and processed fruits and vegetables. The bill also mandates that the EPA register all new and old pesticides. Chemicals that cause "unreasonable adverse effects" will not be registered, according to this piece of legislation. The bill also covers imported produce, calling for the rejection of any imports with unregistered pesticide residue or tolerance-excessive residue of any sort.

Tomatoes. Florida tomato growers compete with Mexico for winter tomato sales. In 1992, Mexican farmers were able to deliver tomatoes to the U.S. border at about half the $9 production cost of a Florida-grown 25-pound box of tomatoes. However, in 1996, after receiving petitions from concerned growers, the United States and Mexico reached an agreement that would place a lower limit on the cost of a 25-pound box. The pact does not restrict the amount of tomatoes the United States imports; instead it ensures price equity. The tomato processing business had been very profitable and the industry expanded quickly, resulting in over production and excess capacity. Even though processing tomato farmers reduced acreage by 25 percent in 1992, the California yield was about 7.4 million tons of processing tomatoes.

California, Mexico, and Florida also produced the first genetically-altered tomato. After five years of testing, the United States Food and Drug Administration (USDA) approved for public consumption the first genetically altered food in 1994. Tomatoes grown by Calgene Inc. were cleared for distribution to the public under the Flavr-Savr brand name. The tomatoes, which are more expensive than tomatoes grown through more traditional means, were created when scientists isolated the gene that causes tomatoes to soften. They then manipulated its genetic make-up to slow down the softening process, allowing more time on the vine for it to ripen. Public interest groups, however, allege that the altered tomatoes carry a gene that causes the plant to become resistant to antibiotics and charge that the presence of the gene may cause humans to build up the same resistance. Supporters of the process however, argue that health concerns are unfounded and point to the superior taste that results from the procedure. The controversy over the safety of genetically modified food extended into the early 2000s.

Tomatoes have also received some positive media attention as a Harvard medical researcher, Edward Giovannucci, MD, announced a preliminary link between tomato consumption and the reduced risk of developing prostate cancer. Tomatoes contain lycopene, a red carotenoid related to beta-carotene, to which Giovannucci has attributed this salubrious effect. Research on the effects of lycopene continues.

Current Conditions

Per capita vegetable and melon consumption dropped two pounds in 2002 to 439 pounds. An increase in canned and frozen vegetable consumption was offset by a decline in fresh vegetables, due in part to higher prices and recessionary economic conditions. Top vegetable and melon growers in the early 2000s included R.D. Offut Company, Grimmway Farms, Tanimura and Antle, and Dole Fresh Vegetables.

The United States remains one of the largest producers and exporters of canned vegetables, although it has also increased its imports of fruits and vegetables, especially from the Caribbean and Latin America. The value of U.S. vegetable and melon imports in 2002 grew 6 percent to reach $4.8 billion, while the value of exports rose 2 percent to $3.3 billion.

The United States increased its tomato imports by 37 percent in 2002; as a result, imports accounted for roughly 8 percent of total U.S. tomato consumption. Per capita consumption of fresh tomatoes reached a record high of 18.3 pounds that year, despite the decline in consumption of other fresh vegetables. Florida and California harvested the majority of U.S. tomato crops.

The 1996 Farm Bill introduced a new era of market-oriented production that had ramifications on all agricultural sectors. Analysts received the bill favorably because the legislation offered farmers more flexibility and yet protected specialty crop growers from market fluctuations by stabilizing the commodity market. The bill was also expected to promote more sound business practices through the alleviation of surplus production, making U.S. producers more competitive in the twenty-first century. Additional legislation designed to increase the competitiveness of U.S. producers was signed by President Bush in May of 2002. Among other things, the 2002 Farm Bill mandates that vegetables and melons be labeled with their country of origin as of September 2004. Many industry analysts believe this will give U.S. vegetable and melon producers increased brand identity.

Further Reading

"New Origin Labeling Guidelines to Help Consumers and Farmers, Says Florida Fruit & Vegetable Association." PR Newswire. 9 October 2002.

U.S. Department of Agriculture and Economic Research Service. "Vegetable and Melon Yearbook." Washington, DC:2002. Available from http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/VGS/Jul03/VGS2003s.txt .

U.S. Department of Agriculture and Economic Research Service. "Vegetable and Melon Yearbook." Washington, DC:2003. Available from http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/VGS/Jul03/VGS2003s.txt .

U.S. Department of Agriculture and National Agricultural Statistics Service. "Statistics of Vegetables and Melons." Washington, DC: 2000. Available from http://www.usda.gov/nass/pubs .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: