SIC 3679

ELECTRONICS COMPONENTS, NOT ELSEWHERE CLASSIFIED

The Electronic Components, Not Elsewhere Classified industry segment is comprised of firms primarily engaged in manufacturing a multitude of miscellaneous electronic devices. Examples of more popular industry offerings include automobile antennas, oscillators, mechanical rectifiers, solenoids, quartz crystals, and electronic switches. For information on semiconductors, resistors, capacitors, connectors, and coils, see related electronic component industries.

NAICS Code(s)

334220 (Radio and Television Broadcasting and Wireless Communications Equipment Manufacturing)

334418 (Printed Circuit/Electronics Assembly Manufacturing)

336322 (Other Motor Vehicle Electrical And Electronic Equipment Manufacturing)

334419 (Other Electronic Component Manufacturing)

Industry Snapshot

Miscellaneous electronic component manufacturers supply products for five broad areas: communications, such as radios, televisions, and satellite systems; computers and calculators; scientific instruments; military applications, particularly missile and radar systems; and power control and manufacturing equipment, such as machine controllers and industrial robots.

The single largest market for electronic components was radio and television transmission equipment producers, especially satellite services, which in the 2000s was a multi-billion dollar segment of the industry. Telephone and telegraph communications equipment makers were next, and computer manufacturers represented the next largest group of the market.

Other major market segments included: radio and television receiving equipment; guided missiles, space, and aircraft components; X-ray apparatus; and individual consumers. The remainder of output was used in numerous niche markets, such as musical instruments, surgical equipment, children's toys, and surveillance devices.

Products. Most miscellaneous electronic components are used to accomplish or support the primary electronic functions of rectification, amplification, oscillation, and switching and timing. In addition, this industry encompasses several peripheral products, such as headphones and phonograph needles. Finally, some unrelated odds and ends are lumped into this industry, such as hermetic seals for equipment, record cutting styli, and video triggers (except those on remote control devices).

In comparison to the leading edge semiconductors and circuits manufactured in other electronic sectors, the majority of components classified in this industry are low-tech, commodity-like products. The major product groups listed below, for example, were developed during the birth of the electronics industry and remain similar in function to their earliest predecessors. For example, rectifiers, which are used to convert alternating current (AC) to direct current (DC), were one of the first electronic components developed.

Piezoelectric devices, like oscillators, are used in clocks, pressure gauges, communications equipment, and other contraptions. They utilize materials, such as slivers of quartz that can convert high-frequency AC into ultrasonic waves of the same frequency. They also can change a mechanical vibration into an electrical signal. Properly cut quartz crystals, for instance, are used as frequency controls in radios and televisions.

Switches and relays are devices that open and close electronic and electrical circuits. Common switches, which are manually operated, include push-button, rotary, slide, and toggle mechanisms. Types of relays, which are triggered electronically, are timing, electromechanical, and reed. Solid state relays are excluded from this industry. Relays often are activated by a solenoid, which is a uniformly wound coil of wire in the form of a cylinder. Passage of DC through the wire creates a magnetic field that moves a metal (usually iron) core that actuates the relay.

Background and Development

Thomas Edison gave birth to the electronics industry in 1883, 10 years after he invented the light bulb, when he induced electrons to jump from a carbon filament to a metal plate inside a vacuum tube. Edison did not exploit this discovery. Lee De Forest, another American, patented a tube based on Edison's concept in 1906. De Forest's discovery marked the beginning of practical applications in electronics.

Many of the products in the miscellaneous components industry, such as piezoelectric devices, relays, and rectifiers, were developed during the initial stages of the electronics revolution. Wireless communication systems, for example, were pioneered by the British Marconi Company. The National Electric Signaling Company of the U.S. General Electric Company, which was formed by Edison interests, led the development of lighting, phonograph, and other electrical equipment. Later, Westinghouse and the Radio Corporation of America made significant contributions to component advancements.

Intense development efforts during World War I spurred electronic component improvements. Piezoelectricity, for example, had been discovered in 1880. Not until World War I, however, was it applied—piezoelectric devices were used to produce underwater acoustic waves in an early form of submarine-detecting sonar, and later as control devices in radios.

The popularization of the radio after World War I, combined with the proliferation of commercial broadcasting, generated huge demand by the general public for radio components during the 1920s and 1930s. Although television was invented during the late 1920s and 1930s, World War II delayed the expansion of television broadcasting. But World War II spawned huge advancements in electronic components such as radar, as electronic research expenditures reached $1.5 billion per year.

Integrated circuits that were introduced in 1958, as well as other advanced semiconductors that were popularized during the 1960s and 1970s, threatened to displace some components that were electromechanical or moved electrons by heat. Instead, these devices served to expand the breadth of the electronics industry, resulting in demand growth for most traditional electronic components.

The proliferation of military electronics, particularly during the Korean War, and of consumer electronics during the 1950s, resulted in massive industry expansion. Likewise, the introduction of microwave communications, computers, electronic scientific apparatus, and aerospace equipment during the 1960s and 1970s resulted in huge new markets for all types of switches, rectifiers, piezoelectric devices, and other miscellaneous components. Indeed, as new applications for electronic components mushroomed, industry revenues surged to about $13 billion by the late 1970s.

The 1980s and 1990s. Demand for all electronic components surged during the 1980s, ramrodded by the global explosion of personal computers and peripherals, telecommunications equipment, and the introduction of electronics into a broad range of industrial and consumer products. Worldwide sales of integrated circuits, for example, swelled 464 percent during the decade. U.S. shipment growth of the miscellaneous electronic components in this classification, however, stagnated. Industry revenues climbed at a meager pace of less than 2 percent per year during the 1980s to about $17 billion, not even keeping up with inflation. The industry fared better than many analysts predicted it would, though, in the face of falling prices and fierce foreign competition from low-cost producers. Industry revenues surged as high as $19 billion in 1984, but then waffled between $15 and $17 billion throughout the remainder of the decade and into the early 1990s.

Realizing that profit opportunities from traditional miscellaneous components were dwindling, many U.S. manufacturers simply abandoned the industry or switched their emphasis to related growing segments of the electronics industry. Other producers maintained profitability through vast manufacturing productivity gains. Importantly, many makers of traditional components maintained a resilient market presence by developing and introducing miniaturized products with greater reliability.

The dominant feature of this industry during the 1980s was consolidation. In an effort to maximize efficiency, take advantage of new manufacturing processes, and increase capital, companies rapidly merged with or acquired their competitors. In fact, the number of industry participants plummeted from more than 3,700 in the early 1980s to less than 2,500 by the late 1980s.

Industry employment peaked in 1984 at 243,000. However, productivity gains, company consolidation, and the movement of some manufacturing activities outside the United States contributed to significant workforce reductions after that year. Employment plummeted to about 160,000 by the late 1980s, a decline of about 35 percent, and was stable going into the early 1990s.

Miscellaneous electronic component producers enjoyed encouraging revenue gains of between 3 and 5 percent per year between 1988 and 1990. Economic recession caught up with the industry in 1991, however, when sales rose a tepid 2.2 percent. Shipments of filter devices, for example, increased 2.2 percent, as did piezoelectric components. Sales of piezoelectric mechanisms, though, had fallen dramatically from a peak of $295 million in 1987 to about $238 million in 1991. Bucking analysts' predictions, relay sales declined only 2.7 percent in 1991, to $495 million, as solid state devices encroached on their market dominance.

As domestic sales of miscellaneous devices continued to sputter in the early 1990s, manufacturers increasingly looked to exports to buoy thinning profit margins. Export growth had been consistently strong since 1989, and cross-border sales had grown to more than $2 billion by the early 1990s. The strongest export markets were Canada, Mexico, Japan, and the United Kingdom. The largest importers to the United States, which were increasingly grasping domestic market share, were Japan, Taiwan, Singapore, Mexico, and Canada. Japan dominated U.S. miscellaneous component imports with a staggering 53 percent share.

In the mid-1990s, economic recovery in the United States and abroad was expected to boost worldwide demand for passive components. In 1995 the value of industry shipments totaled $31.07 billion, and the number of employees grew to 20,300. Although integrated circuits and other advanced devices continued to cannibalize miscellaneous component market share, slow expansion through the mid-1990s was fueled by strengthening computer, telecommunications, and automotive industries.

Exports offered growth opportunities, as well, boosted by the weak dollar and the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994. Imports, though, may rise significantly as U.S. manufacturers move production to low-cost production regions, particularly Mexico and the Pacific Rim.

U.S. miscellaneous electronic component manufacturers were struggling to overcome intense competition from low-cost foreign producers in the mid-1990s. Makers of many traditional products also were striving to retain market share in the face of increasingly popular solid state components.

In this industry filled with miscellaneous low-tech products, one segment displayed promising growth in the late 1990s. Liquid crystal display (LCD) production snowballed as this technology became ubiquitous in the digital revolution of the 1990s. The display market alone generated 1998 sales of $38 billion, with flat-panel displays accounting for about $12 billion in sales. Experts projected that flat-panel displays would fuel growth in the industry, accounting for more than half of the projected $75 billion in sales by 2005.

Another technology poised for potential growth was organic light-emitting diode (OLED) displays, which offered energy-efficiency, high color fidelity, and thumbnail-to-wall size flexibility. FED Corporation of Hopewell Junction, New York, pioneered this technology and continued to tweak it, most significantly developing the ability to graft OLEDs with silicon components. Whereas Thomas Edison's light bulb was essentially a heat-generating device that emitted some light, the OLED display was essentially a light-generating device that emitted some heat; this reversal in the efficiency quotient represented a kind of maturation for this industry.

Current Conditions

By 2003, manufacturers of LCDs were challenged to distinguish their products in some way more recognizable to consumers than brightness and contrast. At this time, they were directing research and development efforts toward short response times, due to consumer demand triggered by the increasing popularity of computer-based games and movie capabilities. In addition, manufacturers were beginning to target products toward the industrial sector, in hopes of increasing the market beyond that of consumers.

In the 2000s, the market for direct broadcast satellite (DBS) was growing exponentially, despite the initial cost to providers in attracting and setting up new customers. Industry leader Hughes controlled DIRECTV, the largest provider in 2004, with 12 million subscribers. Revenues were growing in the double digit percents annually. The company was looking ahead to such innovative services as interactivity capabilities—such as live voting or choosing camera angles—digital video recorders, and high-definition television, according to Hughes President and CEO Chase Carey.

Production jobs in the overall electronic components industry were forecast to fall considerably between 1990 and 2005, according to the U.S. Department of Labor's Bureau of Labor Statistics. Past trends indicated that sales of miscellaneous components would decline at a much faster rate, however. Jobs for electrical assemblers, which comprise about 20 percent of the overall electronic component workforce, were expected to decline approximately 40 percent by 2005. However, employment prospects for management, sales professionals and engineers were less discouraging.

According to the U.S. Industry and Trade Outlook, the industry was expected to continue growing annually through the mid-2000s. The top five countries in terms of U.S. imports were Malaysia, Canada, Taiwan, Mexico, and Japan.

Industry Leaders

Because of the breadth and diversity of its offerings, the miscellaneous electronic component industry was

still fragmented, despite consolidation. Most all hightech companies, such as Hewlett-Packard Co., Tokyo-based Toshiba Corp., NEC Corp., and Fujitsu Corp., participated in the industry to some degree. However, the industry leaders tended to be smaller concerns; most of the top 75 firms in the industry had less than $100 million in sales and fewer than 1,000 workers in the 1990s. Some companies, such as FEI Microwave Inc. and Electro-Scan Inc., specialized in producing a few niche proprietary products. Companies like Texas Instruments and Motorola, which were primarily engaged in producing products in other electronics segments, manufactured miscellaneous components to support other product lines. Other companies produced high-volume commodity components for sale to other manufacturers, like automakers and appliance manufacturers.

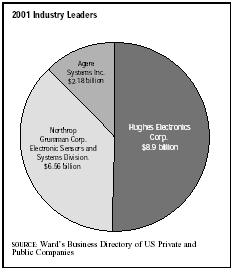

The industry leader in 2001 was Hughes Electronics Corp. of El Segundo, California, with revenue of $8.9 billion and 13,700 employees. For 2003, Hughes posted sales of $10.1 billion. Second was Baltimore-based Northrop Grumman Corp.'s Electronic Sensors and Systems Division. Northrop had 2001 revenues of $6.6 billion and 7,300 employees. Rounding out the top three was Agere Systems Inc. of Allentown, Pennsylvania, with $2.2 billion in revenues and 10,700 employees.

Further Reading

Baker, Deborah J., ed. Ward's Business Directory of US Private and Public Companies. Detroit, MI: Thomson Gale, 2003.

Chin, Spencer. "Display Makers View Industrial Market as Good Fit for Their Wares." EBN, 2 June 2003.

"The Critical Moment When Choosing an LCD is 16 Milliseconds." MicroScope, 4 March 2003.

Hoover's Company Fact Sheet. "Hughes Electronics Corporation." 3 March 2004. Available from http://www.hoovers.com .

"Hughes Announces Full Year and Fourth Quarter 2003 Results." 10 February 2004. Available from http://www.hughes.com .

Stires, David. "Plugging Into Hughes Electronics." Forbes, 23 February 2004.

U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Economic and Employment Projections. 11 February 2004. Available from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/ecopro.toc.htm .

US Industry and Trade Outlook. New York: McGraw Hill, 2000.