SIC 2021

CREAMERY BUTTER

This industry consists of establishments primarily engaged in manufacturing creamery butter.

NAICS Code(s)

311512 (Creamery Butter Manufacturing)

Industry Snapshot

Despite modern sanitary production methods, butter produced early in the twenty-first century is not much different from that enjoyed centuries ago by people who churned milk in animal skins slung from the backs of camels and horses. Butter manufacturing and marketing, a sector of the dairy industry, is extremely regionalized and competitive. The industry's quality standards and farm pricing are highly regulated by the U.S. government. Government price support programs were reduced throughout the 1990s, which led to a more competitive marketplace and more volatility in the prices of dairy products, including butter, by the early 2000s.

Background and Development

Commercial production of butter is a relatively recent development. In 1870 nearly all of the 514 million pounds of U.S. butter was produced on farms. The spreading effects of the Industrial Era and the invention of machinery changed all that. In 1864, a Bavarian brew-master applied the process of centrifugation to butter making. A cream batching machine was introduced in 1877, followed two years later by the continuous cream separator.

Other innovations helped to advance the industry. The Babcock test, perfected in 1890, accurately measured the percentage of fat in milk and cream. Pasteurization insured a high quality of both milk and cream. Additionally, the use of pure cultures of lactic acid bacteria and the invention of refrigeration aided the preservation of quality.

The first U.S. butter manufacturing creamery was built in Manchester, Iowa, in 1871. By 1991, commercial production exceeded 1.3 billion pounds, and Wisconsin and California were the leading butter producers, accounting for 654 million pounds. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 1997 there were 34 establishments whose primary purpose was the manufacture of creamery butter. Wisconsin and California were still primary butter-producing states. Also, the largest U.S. single-site dairy complex was the Land O'Lakes plant in Tulare, California.

Under federal regulations, butter sold in the United States is made exclusively from milk or cream, or both, and must contain at least 80 percent milkfat by weight. Coloring or salt may be added. Butter is labeled by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) as Grade AA, A, or B, according to flavor intensity, texture, color, and salt taste.

Throughout the 1990s butter producers sold their butter products in supermarkets, club stores, and other retail outlets. In addition to individual consumers, butter producers served the foodservice industry (restaurants and fast-food operations), institutions (hospitals and schools), and industrial customers (bakeries). At the retail level, Grade A butter was typically packaged in quarter pound sticks packed four to a cardboard carton, while whipped butter, developed for easier spreadability, was packaged in tubs. Industrial and foodservice packaging ranged from 68-pound blocks to individually wrapped, single-serve pats. Butteroil, the anhydrous form of butter developed to use up surpluses during a period of lowered public consumption, has been used by the confectionery and baking industries and as a cooking oil.

During the 1980s butter consumption slowed as health and calorie-conscious consumers switched to margarine and other spreads. From 1981 to 1991, annual per capita butter consumption increased only slightly from 3.7 to 3.9 pounds. In 1995 supermarket sales of butter were $689 million, down from the 1991 figure of $917.5 million. Total U.S. butter sales in 1995 were $1.3 billion, virtually unchanged from 1991.

To offset the decrease in butter consumption, the industry researched alternate ways to market its product. One way was the use of butteroil (produced by heating butter until its emulsion breaks down then removing the milk serum through centrifugation) as a substitute for other oils in cooking and baking. Butter producers also introduced flavored butters such as honey, garlic, and herb butter, hoping to increase consumer interest.

Current Conditions

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, America actually experienced a shortage of butter and record prices for milk butterfat. Although production increased by 3 percent in 2000, sales continued to outpace output, which pushed prices even higher. In the fall of 2001, retail butter prices jumped to between $4 and $5 per pound as butterfat prices peaked at $2.22. While butterfat prices had declined to $1.05 by mid-2002, retail prices remained high. According to an August 2002 issue of Dairy Field, "Butter consumption was enjoying a modest revival in

the late 1990s, but high prices at the retail level have put a damper on that."

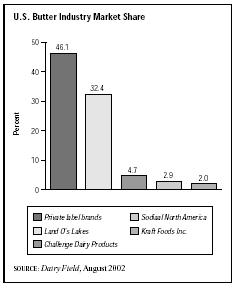

Higher prices also had the effect of boosting sales of private label butter, which held a 46.1 percent share of the butter market in 2002. Sales of private label butter, typically cheaper than name brand butter, grew 20.6 percent between 2001 and 2002, reaching $615.9 million. During that time period, total butter sales grew 15.3 percent to $1.33 billion.

Industry Leaders

The largest butter producing firm in the United States in 2002 was also among the largest of the Midwest dairy cooperatives: Land O'Lakes Inc. This co-op, which had originated to represent farmers in obtaining the best milk prices, grew to become a manufacturer and marketer of butter and other dairy products. Established in 1921, Land O'Lakes led the retail butter industry in 2002 with a 32.4 percent market share. Headquartered in Arden Hills, Minneapolis, Land O'Lakes has the number one brand of butter in the United States and markets more than 600 dairy products. Butter sales in 2002 grew 6.5 percent to $432 million. Challenge Dairy Products, a unit of California Dairies Inc., held a distant second place to Land O'Lakes, with 4.7 percent of all U.S. butter sales.

By the late 1990s, the West Coast had begun replacing the Midwest as the leading producer of dairy products. Many distributors blamed Midwest farmers' reluctance to modernize.

Research and Technology

At the close of the century, the use of recombinant bovine growth hormone (rBGH) to stimulate cows' milk production was the dominant issue in the dairy industry. Manufactured by Monsanto and approved for use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1993 (in use since 1994), rBGH was criticized for its tendency to create udder infections in cows. Antibiotics administered to the cows passed into their milk and, subsequently, into consumers. Critics charged that humans were in danger of developing a resistance to antibiotics, which could prove fatal when needed for disease control. There was also concern that rBGH could cause cancer. Land O' Lakes, a vocal supporter of rBGH, was often targeted by protestors. In early 1997, a Vermont campaign to require labeling of all dairy products containing RBGH milk was struck down by the courts. In the late 1990s, many groups still wanted the use of rBGH stopped; in 1998, for example, the Sierra Club of Canada was protesting its use in the United States, hoping to stall Canadian approval. They were trying to urge Monsanto to conduct more extensive testing. As of 2004, rBGH labeling was not yet a requirement in the United States.

Further Reading

"Butter Prices Explode in Response to Spot Shortages." Nation's Restaurant News, 27 November 2000.

Cook, Julie. "A Matter of Taste." Dairy Field, August 2002.

Hoover's Online. Hoover's Inc., 2000. Available from http://www.hoovers.com .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: