SIC 3269

POTTERY PRODUCTS, NOT ELSEWHERE CLASSIFIED

This industry consists of manufacturers of art and ornamental pottery, industrial and laboratory pottery, unglazed earthenware florists' articles, and earthenware table and kitchen articles, as well as those establishments primarily engaged in firing and decorating white china and earthenware for the trade.

NAICS Code(s)

327112 (Vitreous China, Fine Earthenware, and Other Pottery Product Manufacturing)

Industry Snapshot

The manufacture of pottery products, like the manufacture of vitreous china table and kitchen articles (see SIC 3262: Vitreous China Table and Kitchen Articles ) is an anomaly in twenty-first-century American industry. It is labor intensive and to a large extent involves machinery and techniques that have changed little in the last half century.

Pottery is made of clays that are mixed with other chemicals. Some pottery products are made on modern versions of potters' wheels, and some are glazed and fired at extremely high temperatures to become vitreous china. Pottery that is glazed and fired in a kiln becomes vitrified, or nonporous and glass-like, when the high temperatures cause the glaze to fuse with the clay; this china is both delicate and extremely durable. For this reason, it is used for fine giftware such as bone china figurines and lamp bases.

Competition from abroad was intense. Pottery products were sold in the United States from Japanese, English, Chinese, and Spanish manufacturers, among others. Imports accounted for almost three-quarters of the U.S. gift market. During the first half of the 1990s, weakness in the U.S. dollar helped to even the playing field somewhat, allowing U.S. manufacturers to sell more of their wares in Canada, Taiwan, and Mexico. However, as the decade progressed and the dollar again strengthened, foreign manufacturers regained the upper hand. The weakening dollar in the early 2000s did little to boost exports as other nations also experienced recessionary economic conditions.

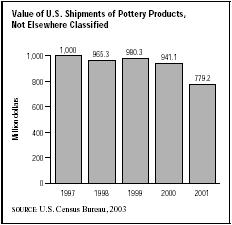

The industry is also closely tied to economic conditions, as many consumers consider art and ornamental pottery to be a luxury. Although the U.S. economy was recovering in the early 1990s, the upturn in the giftware market was slower than in other industries. Even fine china, once considered a staple of the bridal market, was being rejected in the late 1990s by some young couples who preferred to put more money into electronic equipment or more expensive housing. Between 1997 and 2001, industry shipments declined from $1 billion to $779.2 million. Shipments of pottery products, not elsewhere classified, accounted for 67.6 percent of vitreous china, fine earthenware, and other pottery product shipments.

Organization and Structure

The pottery products industry is led by several manufacturers who also create tableware and kitchenware made of vitreous china and semivitreous earthenware. Much of the equipment used by these manufacturers is the same for all of these products. Glazes and kiln temperatures vary widely, however, and the manufacturers often keep their different lines separate. Some manufacturers, for example, create their unglazed red earthenware lines in a separate plant from their semivitreous tableware lines.

The giftware market is critical for these manufacturers. Some of the promotional or commemorative pottery items slid through the recession without suffering, as corporate buyers continued to purchase promotional ceramics at much the same rate.

Background and Development

Porcelain was being made in China as early as the ninth century. By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, fine porcelain art objects were being created in Europe as well. When immigrants came to the United States, they brought their crafting techniques with them. The Ohio River Valley, where manufacturers had easy access to kaolin (the soft, white clay that is essential to the manufacture of china and porcelain), became the first pottery manufacturing center. By the late 1990s, more of the companies working with pottery products were in California, but companies in Ohio and Pennsylvania still accounted for nearly 15 percent of the industry's total shipments.

The Industrial Revolution changed the manufacture of porcelain products just as it had changed other industries. Around the world, potters, who had created hand-thrown ware and then painstakingly decorated their work one piece at a time, began to change the procedures they used. Mass copies of pottery objects became available at lower prices as the processes became more efficient. Some manufacturers objected to the new ways, however, and insisted on maintaining individuality and high quality in their wares.

Potters in the United States also had to adapt to the changing tastes and needs of their communities late in the nineteenth century. They had to compete with increasingly available glass and tin containers, and many of them expanded their product lines to include red earthenware pots, which became the only luxury many consumers allowed themselves through World War I and the Depression. For many U.S. potteries, these flowerpots were the company staple for decades.

During the recession of the late 1980s the U.S. giftware market suffered. Even affluent consumers who purchased artware, stoneware, and earthenware items were becoming more price conscious. Manufacturers had to lower prices or develop newer lines to compensate for losses. However, while the retail market was sluggish, many manufacturers covered their losses by responding to increased demand for promotional giftware and tableware. In the dinnerware market (also covered in SIC 3262: Vitreous China Table and Kitchen Articles and SIC 3263: Fine Earthenware (Whiteware) Table and Kitchen Articles ) more than half of sales were through mass merchants and department stores.

Giftware in the 1990s became increasingly diverse. New designs of ceramic and pottery items reflected interest in the environment and in multicultural themes. Both wholesalers and retailers displayed collections of pottery and stoneware that were reminiscent of specific cultures, or that were politically correct, environmentally friendly, or both. One popular cookie jar was designed to resemble the earth, complete with raised continents. Certain traditional items, such as elegant china and earthenware figures still sold well.

The increasing concern about lead content in earthenware, pottery, and other ceramics led to the establishment of the Coalition of Safe Ceramicware (CSC). In early 1992, the CSC pledged that its members complied with all of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) standards regarding safe levels of lead, with Proposition 65, which required labeling on chinaware warning consumers if a product exposed them to more than 0.5 micrograms of lead per day, and with the California Tableware Safety Program.

Current Conditions

The U.S. economic boom during the latter half of the 1990s was expected to boost giftware sales. However, increasing competition from imports undercut gains for U.S. pottery manufacturers. Shipments of pottery products, not elsewhere classified, declined from $1 billion in 1997 to $965.3 million in 1998, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. While growing consumer confidence boosted the value of shipments to $980.3 million in 1999, this figure declined to $941.1 million in 2000. The U.S. economy crashed that year, pushing the value of shipments down to $779.2 million in 2001. These figures included the shipments of products that were primary and secondary to the industry. Most of the value of product shipments for this industry came from art and decorative ware made either of china and porcelain, or of earthenware and stoneware.

Industry Leaders

In the early 2000s, most of the recognized leaders in the manufacture of pottery products also manufactured fine earthenware and/or vitreous china table and kitchen products. Most industry leaders had been in the business for many years. Pfaltzgraff, founded in 1811 and headquartered in York, Pennsylvania, was recognized as the oldest continuously operating pottery in the country. Operated by the Pfaltzgraff family for generations, the company expanded throughout the 1980s, purchasing another well-known manufacturer of pottery products, Syracuse, in 1983. In 1988, Pfaltzgraff bought Treasure Craft, a California company that was known for its giftware and household ceramic products. Privately held, Pfaltzgraff is not required to disclose details of its financial performance.

Lenox China, founded in 1889 in Trenton, New Jersey, was purchased by Brown-Forman Corp. of Louisville, Kentucky, in 1983. The china company's founder, Walter Scott Lenox, formed the Ceramic Art Company, which made table items as well as gift and art pieces including parasol handles, vases, inkstands, and thimbles. Lenox opened a new facility in 1985 in Oxford, North Carolina, expressly for the manufacture of Lenox China giftware. Other Lenox China plants were in Pomona, New Jersey, and Kinston, North Carolina.

Workforce

Many workers in this industry spend their entire careers perfecting one job. Each job in production is unique, from the creation of the special clay mixture, called slip, to the packaging of the final products. Training a potter takes many years, and most manufacturers in this industry hire production workers with the intention of investing the time required so that the workers learn the craft from top to bottom.

Some plants have a sliphouse, where there are machine operators, mixers, and others who must bring the raw materials to exactly the right consistency before it can be cast. Casters pour the slip into plaster of Paris molds where it dries for a specified length of time. The porous molds draw moisture out of the slip until enough of a shell forms the outlines of the product. If it sits too long, when the rest of the slip is poured out, the shell will be too thick to be glazed and fired. Each manufacturer has its own recipe for the slip and its own methods for casting, but each step is carefully monitored.

After pouring out excess slip, casters and finishers sponge the products, removing coarse edges and seams left over from the mold. In some plants, jigger men work in shaping and forming the clay, and cutters and finishers work in drying and secondary shaping. The pottery where the products are cast can be very dusty during the drying operations. During certain hours each day, all workers are required to wear respirators. The pottery, then known as greenware, must dry, usually overnight, before it is ready to be glazed and fired.

Most glazing is done by a glazer; glazes are sprayed onto one piece at a time. Some glazes are applied by glazing machines. In most factories, loaders place greenware onto tiered carts that can be moved from the casting room through the glazing department and directly through the kilns. Kiln operators and loaders get used to the intense heat needed to vitrify the greenware. Glazes and ceramics become melded together, forming the impermeable vitreous china. Kilns reach temperatures of up to 2,300 degrees Fahrenheit; therefore, they are almost never shut down, since it would take close to two weeks to get them back up to firing temperature.

Once they emerge from the kiln, the products are checked by inspectors and chosen by selectors. Pieces that are slightly defective are sent back for regrinding, reglazing, and refiring. Many items, especially in giftware, are then specially adorned by decorators. These must also be seen by inspectors before being sent to the packing department.

The manufacturers also have support departments, including machine shops, where machinery can be repaired or cleaned; mold departments, where plaster molds are made and repaired; and warehouses that handle shipping and receiving. They also have administrative departments covering human resources, public relations, corporate development, and other general business needs.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, many of the plants where pottery products were manufactured were unionized. Some of the organized workers belonged to the Glass Molders, Pottery, Plastics and Allied Workers International Union (GPPAW). The GPPAW published a health and safety manual that identified potential workplace hazards for manufacturers of dinnerware, chinaware, and other pottery products. The unions were also active in negotiating wages, certain workplace standards, vacation time, and other benefits for their members.

According to U.S. Census Bureau, 18,696 people worked in the vitreous china, fine earthenware, and other pottery products industry in 2000, compared to 23,253 in 1997. Of this total, 15,135 worked in production. The average hourly wage for production workers in 2000 was $11.20, up from $10.02 in 1997, $7.06 in 1987, $5.96 in 1982, and $3.87 in 1977.

America and the World

In the early 2000s, the U.S. pottery industry faced heavy world competition, especially with Japan, Taiwan, China, and England. For much of the 1990s, the weaker U.S. dollar meant that exports from the United States increased, especially to Taiwan, Canada, and Mexico, while foreign products became more expensive and made domestic products more attractive at home. However, as the dollar strengthened later in the decade, competition from imports gathered strength once again.

U.S. potteries tried to capitalize on the desire of local consumers to buy products made in their country. They tried to keep close tabs on marketplace trends and to respond with items American consumers would want.

Research and Technology

Much of the technology employed by the pottery industry in 2004 was the same as it was centuries ago. The factories in the early twentieth century used more machinery to produce more pottery, but the essential ingredients remained. For example, hand-throwing techniques were supplemented with hand-jigger machines. Today's potter's wheel is electric, and a jigger blade is usually used to quickly shape a plate. Salt glazing was gradually replaced by dip-glazing, in which the ware was dipped before firing. In some plants, pottery is glazed automatically, while in others, glazers spray glaze onto only one item at a time. Only slight changes have been made in the recipes for clays, the shape and type of molds, casting methods, and firing techniques.

However, some manufacturers were looking in new technological directions to keep foreign competitors at bay. Pfaltzgraff was the first in the industry to have a dry press system, which formed, finished, decorated, glazed, and fired pottery products in one continuous process. It vastly increased productivity, especially for plates and small bowls. The company also invested in a CAD/CAM system that provided 3-D images of finished products so that problems could be anticipated and corrected before production began. In 1997, the company estimated that it saved 9 to 18 months in production and discarded onequarter fewer pieces of china because of the CAD/CAM improvements.

The larger changes for the pottery products industry were in the general way business was conducted. In order to survive, these small, family-owned potteries had to become businesses that competed not only in the national but also in the international market. It was no longer enough to make a quality product. Manufacturers also had to market and sell their wares, create new innovations, and pass on to a new generation of potters the desire to keep this age-old craft thriving.

Further Reading

U.S. Advanced Ceramics Association. Advanced Ceramics Technology Roadmap: Charting Our Course. Washington, DC: December 2000. Available from http://www.advancedceramics.org/ceramics_roadmap.pdf .

U.S. Census Bureau. "Statistics for Industry Groups and Industries: 2000." February 2002. Available from http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/m00as-1.pdf .

——. "Value of Shipment for Product Classes: 2001 and Earlier Years." December 2002. Available from http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/m01as-2.pdf .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: