SIC 5154

LIVESTOCK

Establishments falling under this classification are primarily engaged in buying and/or marketing cattle, hogs, sheep, and goats. This industry also includes the operation of livestock auction markets. Establishments primarily engaged in the wholesale distribution of poultry are classified in SIC 5144: Poultry and Poultry Products; companies involved in the buying and selling of horses are in SIC 5159: Farm-Product Raw Materials, Not Elsewhere Classified.

NAICS Code(s)

422520 (Livestock Wholesalers)

Industry Snapshot

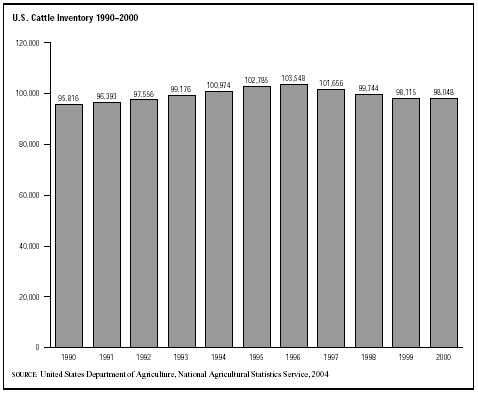

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, in conjunction with the National Agricultural Statistics Service there were 94.9 trillion cattle reported in the United States in January of 2004. The highest concentration was in Texas with 795 establishments that are engaged in this industry. Iowa followed with 386, and California with 260. The industry employed 32,953 workers and generated $5.7 billion in sales for 2003. The average sales per individual establishment was approximately $1 million.

Cattle represented the highest number of establishments with 2,459 and more than 41 percent of the market value. Livestock numbered 1,835 and accounted for more than 30 percent of the market. Auctioning of livestock had 1,382 establishments and more than 23 percent of the overall market. Combined, their sales totaled $5.3 billion. Hogs, goats, and sheep accounted for 258 establishments.

The marketing of livestock in the United States is conducted by a variety of businesses ranging from the order buyer who operates out of the front seat of his car to the video auction that sells cattle by beaming pictures of them to a satellite orbiting the earth. The livestock marketing business has evolved from the days when stockmen would send their livestock to a terminal market without any idea of the price they might receive. Terminal markets and commission agents still thrive in the ever-changing world of livestock marketing, but they have been joined by modern day merchants who use computers, video uplinks, fax machines, and cellular phones to market livestock.

Firms involved in the wholesale marketing of cattle, sheep, hogs, and goats include such diverse operations as stockyards, commission firms, order buyers, dealers, brokers, auction markets, and video auction companies.

Livestock are consigned to auctions by ranchers, hog operators, sheepherders, and other stockmen to be sold by the chant of an auctioneer. Because trucking is a costly expense, most often stockmen will send their livestock to the nearest auction market. This may be ten minutes or ten hours away by truck. These auction markets are usually individually owned—only a handful were owned by conglomerates. The owner of the auction receives a commission or a per head fee for selling the livestock in addition to charging for the feed consumed while the livestock are in the auction yard. Typical commissions range from 2 to 3 percent or about $7.50 per head.

One of the largest cattle auctions in the country where the cattle are actually herded through an auction ring was located in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Here cattle are sold nearly every day of the week. The auction in Norfolk, Nebraska was one of the largest auctions in terms of the number of species sold. There might be a hog auction taking place in one sale ring and a dairy cattle auction in another ring on the same premises on the same day. This is an exception, however, as most of the auction yards in the country conduct sales once a week. Sheep, dairy animals, goats, hogs, horses, and cattle are sometimes offered on the same day at the same location.

Commission agents are still used at some auctions around the country—the auction at Oklahoma City being the largest. This practice is a holdover from decades ago when ranchers would send their livestock to a commission agent located at any of the larger stockyards, such as those located in Chicago. These agents would then be responsible for the care and feeding of the livestock and the selling of them once they reached the yard, and would receive a commission based on how much the animals brought at market.

Livestock is usually sold by the pound except in the case of breeding animals, which are usually sold by the head. For example, a breeding bull may bring $2,000 to $3,000, whereas a steer destined for a feedlot may sell for $60 per hundredweight. Old cows being sold for slaughter are usually sold one at a time. When a rancher sells his yearly production in the form of calves or lambs, however, the drafts may be composed of several dozen or even hundreds of head. In the latter instance the livestock are weighed and priced per pound. Steer cattle and heifers are usually sold separately, whereas a group of lambs or hogs may include both sexes.

Sitting in the auction arena are a variety of buyers who make their living attending several auction sales each week. They may be order buyers working on a per head or per pound fee, or they may be employees of a feedlot or a packing house. Order buyers may have several orders at the same auction sale. A feedlot manager may have called and wanted steers for the feedlot or a rancher may have phoned with an order for heifers suitable

for breeding. Order buyers often to represent several interests at the same sale, although they usually try to avoid having more than one order for the same classification of livestock. The order buyers keep careful track of both the number of livestock they buy and the weight, which is flashed on an overhead "scoreboard." Order buyers are highly skilled and are paid on a commission basis, which is usually "fifty cents per hundred"—this means that on a purchase of a $500 animal the order buyer would be paid $2.50.

At ringside buyers convey their desire to bid by sending slight body signals to an auctioneer who has learned his chant at one of many auction schools. The livestock are sold rapidly with as many as 50,000 head per day being sold. In the case of video auctions, it is not unusual to see the ownership of 60,000 head of livestock change hands in a single day.

Organization and Structure

Some ranchers prefer to sell their livestock "in the country," which is the popular way of saying that buyers come to the ranch or farm and purchase the animals directly from the owner rather than from an auction market. The livestock are weighed on a ranch scale that has been checked and sealed by representatives from state or county weights and measures. In most cases the same order buyers who sit in on the auction scour the country looking for livestock to buy "in the country."

In discussing livestock marketing, a distinction must be made between classes of livestock. Feeder cattle or calves that are just being weaned are most often sold at auction. Many feeder pigs and lambs are still sold in this manner. But most cattle, sheep, or hogs that are older and ready for slaughter are sold directly to a packer buyer. Packer buyers are given "show lists" from major feed yards, and they bid on the cattle either in person or over the phone.

Often cattle and hogs are actually fed by the packing plant owner. This is known as "captive supply," and at times the captive supply of fed cattle in the United States exceeds 20 percent. This is cause for worry among independent livestock producers who feel that if the "Big Three" meat packers—IBP, Monfort, and Excel—are able to feed their own cattle, they can in some way control the market price for all classes of cattle. They would supposedly do this by withholding their cattle when supplies were large and using up their own supplies when livestock in the country were in short supply.

How livestock are marketed in the United States varies depending on what species is being merchandised. Hogs, for example, are marketed in a fashion similar to poultry—the animals are raised under contract to large packers. Although feeder pigs are still sold at auction, the tendency is toward more vertical integration and more contractual arrangements. In addition to this method there are also several hog buying stations, situated primarily in Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana, to which hogs are delivered, weighed and sold to a packer.

Purebred livestock, boars, rams, bulls, and other registered animals to be used for feedstock production are sold either at auction or by private treaty. At auction the animals are usually sold one at a time, with the auctioneer being paid 1 percent of the selling price and the sales manager receiving a commission of about 5 or 6 percent. In many farm or ranch production auctions, however, there are no sales managers, so that expense is eliminated. Private treaty sales occur when a rancher goes to the farm or ranch and purchases the animals directly from the breeder who produced them.

Legal Aspects. Many of the anti-trust laws in the United States were passed as a direct result of the problem of monopolization of the meat industry. On August 15, 1921, the Packers and Stockyards Administration was formed to police the livestock marketing industry. The P and S, as it is commonly called, works to insure the integrity of the livestock, meat, and poultry markets. This is accomplished through fostering fair and open competition and guarding against deceptive and fraudulent practices that could affect meat and poultry prices.

Producers, consumers, and the entire industry are protected by the P and S from unfair business practices which can unduly affect meat and poultry distribution and the price of meat at every level, from the ranch gate to the super market shelf. The P and S sends auditors to the various livestock marketing agents to review accounts and insure that the marketing agencies are properly bonded.

Commission firms, auction markets, dealers, and order buyers are required to be bonded as a measure of protection for livestock sellers. The size of the bond is based on the volume of business and is generally an average of two business days or a minimum of $10,000. A dealer in livestock must be bonded to legally operate.

It is the primary function of the P and S to insure that commission firms, auction markets, order buyers, and dealers remain financially solvent. The administration is also called upon to rid the industry of the unscrupulous traders who occasionally surface. Rules that livestock dealers must abide by include the prompt pay law, whereby consignors or owners of livestock must be paid promptly, usually by the close of business on the day after the transfer of possession. For example, if a cow buyer sitting on the auction seat buys a load of cattle, the livestock may be loaded and sent to the packing house but the packer must legally pay for those cattle on the day after they have been purchased. Another way the P and S insures that merchandisers remain solvent is by keeping an eye out for "check kiting," which is merely swapping checks by placing them in two or more bank accounts for the purpose of creating a "float" or inflated balance.

The P and S also ensures that all firms engaged in livestock merchandising are playing on a level playing field. Tariffs or charges must be published, and auction markets cannot legally offer free trucking, price guarantees, or discounted commissions as an incentive for a rancher to send his or her livestock to one auction as opposed to another—doing so can result in a fine of $10,000 for each infraction.

In the intricate, competitive world of livestock marketing, no single factor is as important as the accurate measurement of livestock weight. Employees of the Packers and Stockyards Administration check the scales which are used to weigh the livestock on a regular basis. Scales must be tested by an approved weigh master for accuracy at least once every six months.

A principal trade organization for the livestock marketing sector has been the Kansas City-based Livestock Marketing Association (LMA). In addition to lobbying Congress and state legislatures, the LMA is also in the insurance business and provides bonding for the various marketing agencies. The LMA's Board of Trade issues "hot sheets" notifying the industry of unscrupulous dealers and firms that are no longer solvent.

Background and Development

After experiencing declining beef demand throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the industry saw beef demand rise by 4.59 percent for the third quarter of 1999 as compared to third quarter 1998 demand, according to the National Cattlemen's Beef Association (NCBA). The annual rate of decline began to slow in the late-1980s, and started to flatten in 1996; third quarter 1999 represented the first sustained gain in beef demand, following on the heels of a significant increase during the previous quarter, as compared to the second quarter of 1998, according to the Beef Demand Index, independently tracked according to USDA data. In a presentation to the Beef Summit '99, Randy Bloch of the Denver-based market research firm Cattle-Fax attributed rising demand to increased consumer spending and per-capita consumption. A more telling revelation is the fact that consumer demand sustained growth in the face of record-high beef supplies, which drove prices up, surprisingly, in defiance of economic laws of supply and demand.

A growing trend in the beef business in the 1980s and 1990s was the custom feeding of cattle. This means that a rancher places his cattle in a feedlot and pays for feed and yardage expenses and then sells the cattle to a packer when they are ready for processing. In so doing, he maintains ownership of the cattle all the way through the feeding phase, which generally lasts from 120 to 200 days. The cattle are often sold on a grade and weight basis, meaning that the price per pound is determined by the quality of the meat carcass.

Despite a plethora of new methods of marketing livestock, the auction market remained, in the 1990s, the primary agent for assisting in the transfer of title for various species of livestock. As of the late 1990s, 1,500 livestock auctions existed in the United States according to the Livestock Marketing Association (LMA); a variety of livestock were sold on a weekly and sometimes daily basis at these auctions. In addition, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) identified about 19,000 livestock sellers—feedlots, farmer-feeders, auctions and dealers. Combined, beef and pork accounted for 68.4 percent of the meat market, with beef controlling the largest chunk at 40 percent.

According to November 1999 projections, Cattle-Fax extrapolated yearly beef supplies to reach 27 billion pounds, a 2.5 percent increase over 1998 supplies. Simultaneously, consumer spending rose by $1.5 billion to $36.7 billion for the first 3 quarters of 1999, a 4 percent increase compared to the same period in 1998. November projections placed 1999 consumer spending at $48.56 billion, a $2 billion increase over 1998 results. Per capita spending experienced its greatest gain since 1990, according to the projected growth of $5 per capita to $178 by the end of 1999, as compared to 1998 per capita spending. The increase in beef prices by 4 cents in 1999 compared to prices the year before contributed to some of the spending increase, while increasing per capita beef consumption also contributed to some of the increase. Per capita beef consumption rose 0.9 percent in the first three quarters of 1999 compared to September 1998 figures, with projections calling for a 1.6 percent increase over the entire year, compared to 1998.

The NCBA attributed increased beef demand to several factors: increasing exports, the strong domestic economy, rising wages, low inflation, and low unemployment rates. However, NCBA CEO Chuck Schroeder cautioned against over-optimism, reminding the industry of the changing consumer profile. Increasingly, consumers were becoming less knowledgeable about the intricacies of cooking red meat properly while also calling for more convenient preparation methods, prompting the industry at the retail end to transform to more user-friendly packaging with clear cooking instructions and recipes and also packaging pre-fabricated meals and pre-cooked meats to enhance convenience.

In the 1990s, the livestock marketing industry was at something of a crossroads. Would it operate according to the rules of vertical integration, whereby livestock would no longer be sold at auction or "in the country," but instead be under contract from the day of birth to the day of processing? Or would the auction market remain intact? Though auctions have not even started to fade, contract purchases offer packers a distinct financial advantage. For example, packers spent $1.75 to $2.00 less for contract cattle per hundredweight than they did for auctioned cattle. The USDA predicted that contract purchasing would increase, especially in the cattle and hog markets.

Also, the USDA reported in a 1996 study that out the 19,000 operations selling livestock, the 152 largest sellers accounted for 43 percent of the cattle sold. The USDA noted that concentration within the livestock industry seemed to spread to the sector responsible for selling livestock just as it had to other sectors such as packing and feedlots.

In the area of sheep marketing, another problem had surfaced by the mid-1990s—the market had become extremely concentrated, and lamb raisers had only two or three buyers in the entire United States. This has caused the Western Organization Resource Council to call on the U.S. Attorney General and the Justice Department to investigate the situation and to enforce antitrust legislation.

Likewise, the beef packing industry had become increasingly concentrated at the end of the 1990s. In 1994, just three firms in the beef packing Industry—IBP, Monfort and Excel—processed 80 percent of all fed cattle and were increasing their market share cumulatively at the rate of 5 percent per year. When Upton Sinclair wrote The Jungle, a graphic 1906 novel that portrayed the wretched lives of workers in Chicago's meat packing plants (and the impetus behind much antitrust legislation in the food industry), the five largest meat packing firms did not control as much of the slaughter as the "Big Three" do in the modern era. The general feeling among many livestock producer groups is with fewer buyers the lack of competitive bidding will not provide true market discovery for their livestock. The USDA has persistently urged Congress to take action against the large meat-packing companies, launching study after study to reveal their effect on livestock pricing.

Current Conditions

On May 20, 2003 a ban was issued on Canadian cattle imports and products, as a result of a cow testing positive for bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), commonly known as "mad cow disease." A report released by the USDA in April 2004 ended the ban on the Canadian beef industry and reopened the border for trade. This further prompted the USDA to investigate an identification plan in conjunction with the state animal health officials and individual livestock industry groups. This group is called the National Identification Development Team. They will be working on a country-of-orign labeling (COOL) system, or "national standardization program that can identify all premises and animals that had direct contact with a foreign animal disease within 48 hours of discovery." This would enhance the current Federal and state labeling requirements under the U.S. Farm Act.

The total number of cattle on feedlots in the United States totaled 10.6 million in 2003. That number was down from 11.6 million or eight percent in 2002. The United States consumed 3.86 billion pounds of red meat in 2002, while the cattle slaughtered totaled 2.77 million heads. The total number of cattle and calves on feedlots as of January 2004 numbered 11.2 million. There were 6.84 million steers and steer calves that were also included in the inventory. The red meat consumption totaled 3.88 billion pounds in December 2003, while cattle slaughter totaled 97.5 thousand heads of cattle. According to Cattle—Fax beef production for 2004 was expected to decrease to about 25 to 30 pounds per week. This was a decrease of 4.5 percent over 2003.

The United States Department of Agriculture issued its projections through to 2013. It was estimated that the U.S. consumers would spend less on red meat over the next ten years by about 1.8 percent. The total per capita would decline from approximately 185 pounds in 2003 to about 181 pounds, but is expected to stabilize by 2013. The United States exports are expected to rise as the demand for meats increase, however the domestic market is the United States main source. The total meat exports only accounted for 11 percent of the value of U.S. meat in 2003. That number is only expected to increase not more than 12 percent by 2009.

Research and Technology

Nearing the end of the century, one of the ways in which the livestock marketing sector has responded to increased packer concentration is through the use of video auctions. As mentioned earlier, this relatively new tool allows cattlemen to offer their livestock for sale to buyers all over the country through the use of modern day telecommunications tools. Videotaped pictures of consignments of livestock are beamed to a satellite on a predetermined sale day, and buyers can view the livestock on their own television sets, providing they are linked to a satellite dish. While they are viewing the livestock, they can call on the telephone and take part in a regular auction. This way, livestock only have to be moved once—to the new owner—thus avoiding the costly and time-consuming task of trucking animals to an auction market.

In video auction, buyers may come from down the street or across the country. The real value of video auction is the sellers have a free and open market to a much wider audience of potential buyers. The livestock are usually less stressed and healthier when sold in this manner. But descriptions of the livestock must be accurate when the buyers cannot view the animals in person. Another benefit of video auction is if a major buyer stays off the market that day, the seller does not suffer because there are plenty of other buyers to take his place.

Large video auction companies stage either monthly or biweekly sales. Western Video Market, headquartered in Cottonwood, California, is actually a consortium of auction markets that are using the video sales in combination with their own weekly, live animal sales. Superior Livestock Auction, with headquarters in Brush, Colorado and Fort Worth, Texas, on the other hand, has more than 300 agents in the country filming consignments and delivering the livestock to the new buyers. Superior was selling more than one million cattle annually by 1994; Western Video had sold more than 60,000 head in just a single day. Superior was also selling other species of livestock, including ostriches.

The marketing of livestock has come a long way from the days when cattle were herded up the Goodnight Trail in an attempt to find buyers. In the modern era the most up-to-date electronic communication tools are being used to market livestock of all species. There has also been a great deal of experimentation taking place with computer listings of livestock and computer auctions. These changes have been revolutionary for an industry steeped in tradition. One thing remains constant however; in the world of livestock marketing the transaction is bound by an honor code that has disappeared in other industries. Multi-million dollar deals are still consummated without a written contract—the marketing of livestock is still very much a handshake business between gentlemen.

Further Reading

"California Livestock Review, January 2003." United States Department of Agriculture. Available from http://www.nass.usda.gov/ca/rev/lvstk/4011vsna.htm .

"California Livestock Review, January 2004." United States Department of Agriculture. Available from http://www.nass.usda.gov/ca/rev/lvstk/301vsna.htm .

"Cattle—Fax Weekly Feature." 4 March 2004. Available from http://www.cattle—fax.com/feature .

D&B Sales & Marketing Solutions, 2003. Available from http://www.zapdata.com .

Hawkes, Logan. "U.S. Reopens Border to Canadian Beef." 19 April 2004. Available from http://agriculture.about.com/cs/madcowsisease/a/041904_p.htm .

"January 1 U.S. Cattle Inventory 1868-2004." United States Department of Agriculture. National Agricultural Statistics Service. Available from http://www.usda.gov/nass/aggraphs/cattle.htm .

Krissoff, B., F. Kuchler, K. Nelson, J. Perry, and A. Somwaru. "Country—of—Origin Labeling: Theory and Observation." United States Department of Agriculture. Economic Research Service. January 2004. Available from http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/WRS04/jan04/wrs0402/wrs0402.pdf .

"USDA Agricultural Baseline Projections to 2013." United States Department of Agriculture. Economic Research Service, February 2004. Available from http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/usda/usda.html .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: