APPRENTICESHIP PROGRAMS

Apprenticeship programs involve on-the-job training coupled with in-class support for students before they directly enter the workforce. Apprenticeships also are called dual-training programs because participants receive training both in the workplace and at school. Apprenticeship programs have proven extremely effective in smoothly transferring school-related skills to pragmatic workforce application.

THE GERMAN MODEL

Apprenticeship programs were first developed in Germany, where they have received worldwide attention. As Gitter and Scheuer note: "The comprehensive German apprenticeship system is often seen as a model for an improved school-to-work transition" (1997). Perhaps the reason the German model is so successful is the commitment of time both parties invest in the apprenticeship—usually three or more years. This commitment recognizes apprenticeship as a critical educational and training crossroad.

Also contributing to the acceptance of the German model, the Federal Ministry of Education regulates each occupation's training requirements and the ultimate rewarding of completion certification to apprentices. It also provides the framework for the working agreements between apprentices and employers.

Wages for apprentices generally are one-third of the standard employment rate in a given occupation. These wages are fixed across companies regionally through collective agreement of participating employers.

Rainer Winkelmann identifies three hallmark features of the German apprenticeship model: "it is company-based, it relies on voluntary participation by firms, and it generates portable, occupation-specific skills" (1996). Additionally, apprenticeships are funded by the individual companies involved, rather than through state funding or payroll taxation. Actual pay varies greatly according to the nature of the apprenticeship.

Traditionally, apprentices must find their own apprenticeships. In Germany, this often is accomplished through the potential apprentice's own personal connections or initiative. Additionally, Germany's Federal Employment Agency helps to place applicants with firms seeking apprentices. A range of Web sites are available that provide databases of employers offering apprenticeships, searchable by occupation. Though apprenticeships are in no way guaranteed, the vast majority of Germans have participated in an apprenticeship. Indeed, 71 percent of the German labor force had undergone a formal apprenticeship in 1991. Moreover, this figure is misleadingly low, since it does not include those Germans participating in alternative on-the-job training in specialized training schools for health care professionals, hotel workers, or civil servants.

APPRENTICESHIPS VS. INTERNSHIPS

Apprenticeships differ from the internship model more commonly practiced in the United States and Canada. Internships offer essentially minor workplace exposure over a comparatively short time. The internship is seen as merely augmenting the more important coursework. The nature of the internship may not even be set by the employer; instead, it might be determined by the educational institution with the goodwill of the host company. The benefit to the employer in an internship is often negligible, with the long-range benefit of a better qualified employment pool. If the intern contributes to the organization in more than a superficial way, it is an added benefit rather than an expected outcome, although having an intern pool does allow a company to prescreen potential new employees before hiring them permanently. Finally, the internship tends to be an isolated, short-term project as opposed to the four- to five-year commitment of most apprenticeship programs.

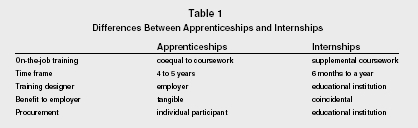

In many respects, apprenticeships are the diametric opposite of internships (see Table 1). In an apprenticeship, the work-related experience is central, with the company, rather than the educational institution, determining the terms of study. In apprenticeships, the coursework is coequal (rather than supplemental) to the on-the-job training. In apprenticeships, the employer expects to receive an immediate tangible benefit from the work carried out by the apprentice, in addition to the long-range benefit of a better qualified employment pool.

BENEFITS OF THE GERMAN MODEL

Gitter and Scheuer credit apprenticeship for the fact that, "with the exception of those with a postsecondary education, the unemployment rates in the United States are more than double those in Germany

Differences Between Apprenticeships and Internships

| Apprenticeships | Internships | |

| On-the-job training | coequal to coursework | supplemental coursework |

| Time frame | 4 to 5 years | 6 months to a year |

| Training designer | employer | educational institution |

| Benefit to employer | tangible | coincidental |

| Procurement | individual participant | educational institution |

for groups with a comparable education" (1997). Couch identified increased earnings for those participating in apprenticeship programs. In all, as Gitter summarizes, "The apprenticeship-trained worker is more likely to earn more money, work more hours per year, and rise to supervisory status than are workers who have learned the trade through other methods" (1994).

EUROPEAN CRITIQUES

OF THE GERMAN SYSTEM

Germany has the longest history of apprenticeships, but it is not alone in its application. Several other European nations also have embraced the concept, most notably in Switzerland, Austria, Denmark, and in recent years, Great Britain. Yet, not all Europeans have embraced apprenticeships. Indeed, the apprenticeship system has come under attack within the European Union. As Roy Harrison indicated, the issue focuses on "the degree to which vocational qualifications should be harmonised at a European level" (1997).

While defenders of the apprenticeship system point to the tangential skills and work-related benefits of the model, they fail to address European-wide concerns that employers would favor the apprenticeship model, thus showing a preference for citizens of nations like Germany and Austria that support the system on a wide scale. Thus, in 1995 the European Council of Ministers met to discuss the difficulties imposed by the German model. In particular, the ministers expressed concern that apprenticeships disrupted the European goal of eliminating preferences for employees from one EU nation over another. The ministers, as Harrison explains, "stressed that a European area in qualifications and training cannot be established while countries continue to distrust the quality and value of each others' qualifications" (1997).

GREAT BRITAIN'S APPROACH

In 1995 Great Britain introduced Modern Apprenticeship. Modern Apprenticeship added flexibility into the program, with no set duration of training as a requisite for government funding. This helped to make apprenticeship more palatable to employers. Additionally, Great Britain does not nationally legislate apprenticeship as do other European countries. Rather, guidelines are sent out from the Department of Education and Skills that are left to open interpretation from varying geographic and occupational sectors.

While a small number of British apprentices obtain employment directly from an employer, most are directed through the government Learning and Skills Councils. Oftentimes, it is the training provider intermediary, rather than the employer, who conducts the assessment of the apprentice. However, complex requirements for receiving government funding for apprenticeship programs are often daunting to the private sector. Therefore many of the apprenticeships in Great Britain involve government-supported training programs and areas of occupation.

APPRENTICESHIP IN THE UNITED STATES

Even as apprenticeships have begun to come under debate in Europe, they have begun to gain wider acceptance in the United States. The apprenticeship programs taking root in the United States remain uncoordinated and hosted by a wide variety of sources. Some are sponsored by German companies themselves. For example, Siemens, the Munich-based multinational, has apprenticeship programs associated with its plants in Lake Mary, Florida; Franklin, Kentucky; and Wendell, North Carolina. Similarly, the Robert Bosch Corporation has set up apprenticeship programs linked to its Charleston, South Carolina, facility. Other German companies also have brought in apprenticeship programs in full or in part to their U.S. operations.

Other apprenticeship programs are sponsored by non-German companies. For example, Illinois-based Castwell Products (a division of Citation Corporation) runs an apprenticeship program for its foundry. As with several other U.S. apprenticeship programs, applicants come from the factory floor—not from secondary school. Nonetheless, the apprenticeship program imitates the German model in most other respects. Castwell's participants undergo a four-year apprenticeship involving eight college courses related to their work, and a rotation every six months for on-the-job training under a different tutor.

Other U.S. apprenticeship programs are cooperative efforts between secondary schools and companies, coordinated through trade associations. Such programs are not accurate representations of the German model, but tend to be modifications inspired by the European apprenticeship system. For example, the Tooling and Manufacturing Association of Park Ridge, Illinois, jointly set up apprenticeship programs with local high schools and manufacturing firms. The on-the-job training is coordinated with job-related coursework at the high school and culminates either in an associate's degree through the summer internship courses, or entry into the Illinois Institute of Technology's four-year manufacturing technology program at a junior standing. Bethany Paul, the association's apprenticeship manager, points to its success, indicating that "in Illinois only 17 percent of students finish college compared with over 90 percent who finish their four-year apprenticeship program."

Finally, in some U.S. apprenticeship programs governmental agencies have tried to plant the seeds for growing apprenticeship systems directly patterned on the German model. For example, the Rhode Island Departments of Labor and Education coordinated with the Rhode Island Teachers Union and private industry to send representatives directly to Germany and Switzerland to study their apprenticeship models. On their return in 1998, Rhode Island set in place a state-coordinated pilot apprenticeship program involving on-the-job training coordinated with business and technical coursework. In four to five years, the program culminated in a bachelor's degree.

Similarly, the Oklahoma Department of Human Services brought together local chambers of commerce, private companies, and public education organizations to form IndEx, a coordinating body for Tulsa-based apprenticeship programs. Unlike other vocational training, the IndEx programs are actual apprenticeships leading high-school juniors through four years of both academic and on-the-job training with pay for both studies and work training. As an incentive, the organization offers a $1,200 bonus for maintaining a 3.1 grade point average or better (Rowley, et al.).

Yet despite the growing interest from a variety of quarters in apprenticeship programs in the United States, problems exist. Germany has provided apprenticeships of some sort since the Middle Ages. This has led to a cultural receptivity to apprenticeships that may not be as readily transferable to the United States. As Gitter and Scheuer (1997) note, "the key to Germany's success is the country's social consensus on the importance of workforce training for youths." In the end, that consensus may not be easily transferred to the United States.

Issues regarding insurance and liability are arguably much greater factors in the heavily litigious U.S. workplace. German, Austrian, and Danish child-labor laws do not view apprenticeships as child labor because the apprenticeship systems are so deeply entrenched into the cultural understanding of education in those countries. By contrast, in the United States, where apprenticeships are a new idea, no such clear differentiation exists separating firms employing middle-school-age apprentices from companies employing inexpensive and illegal child labor. Additionally, in Germany teachers view apprenticeships as normal. In the United States, teachers may feel threatened by the implication that traditional U.S. education (data notwithstanding) does not prepare students for jobs.

Perhaps the greatest potential impediment to the widespread acceptance of apprenticeships may come from the way in which such programs are seen by labor unions in the United States. In Germany, union ranks are filled with members who learned their occupations through apprenticeships. Moreover, considerably greater labor-management cooperation characterizes the German workplace than in the United States. U.S. labor leaders are likely to be suspicious of apprenticeship programs as a management ploy to employ non-unionized, underpaid student workers. Indiana, for instance, was forced to scrap, for these very reasons, a state-sponsored apprenticeship initiative when local steel unions opposed the program. Still, labor can be supportive as well. Wisconsin passed a state law establishing apprenticeship programs with the full cooperation of the AFL-CIO.

Apprenticeship systems have a long history of successful school-to-work transition in Germany. The German model has achieved considerable success in several other nations such as Austria and Switzerland. Though somewhat modified, it has also achieved success in variant forms in Denmark and Great Britain, although practiced by a considerably more limited number of apprentices and employers. Since the early 1990s the German apprenticeship model has achieved growing attention in the United States. To date, U.S. apprenticeships have been both limited and relatively uncoordinated. Still, the initial programs sponsored both by private and state organizations seem promising, though they face several potential obstacles

David A. Victor

Revised by Deborah Hausler

FURTHER READING:

"Apprenticeship Program Shows A European Flair." Tooling & Production, October 1998, 37–38.

Buechtemann, Christoph F., Juergen Schupp, and Dana Soloff. "Roads to Work: School-to-Work Transition Patterns in Germany and the United States." Industrial Relations Journal 24, no. 2 (1993): 97–111.

Filipczak, Bob. "Apprenticeships From High Schools to High Skills." Training, April 1992, 23–29.

Gitter, Robert J. "Apprenticeship-Trained Workers: United States and Great Britain." Monthly Labor Review, April 1994, 38–43.

Gitter, Robert J., and Markus Scheuer. "U.S. and German Youths: Unemployment and the Transition from School to Work." Monthly Labor Review, March 1997, 16–20.

Hamilton, Stephen F. "Prospects for an America-Style Youth Apprenticeship System." Educational Researcher, April 1993, 11–16.

Harrison, Roy. "Easing Border Controls for Vocational Training." People Management, 18 December 1997, 41.

Lightner, Stan, and Edward L. Harris. "Legal Aspects of Youth Apprenticeships: What You Should Know." Tech Directions, November 1994, 21–25.

"Manufacturers Cultivate 'Home-Grown' Employees." Tooling & Production, July 1997, 31.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Employment Outlook. Paris: OECD, 1994.

Philbin, Matthew L. "Castwell 'Grew Its Own' Maintenance MVP's." Modern Casting, May 1997, 44–47.

Rowley, Wayne, Terry Crist, and Leo Presley. "Partnerships for Productivity." Training and Development, January 1995, 53–55.

Steedman, Hilary. "Five Years of the Modern Apprenticeship Initiative: An Assessment Against Continental European Models." National Institute Economic Review, October 2001, 75.

Winkelmann, Rainer. "Employment Prospects and Skill Acquisition of Apprenticeship-Trained Workers in Germany." Industrial and Labor Relations Review, July 1996, 658–672.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: