DISCRIMINATION

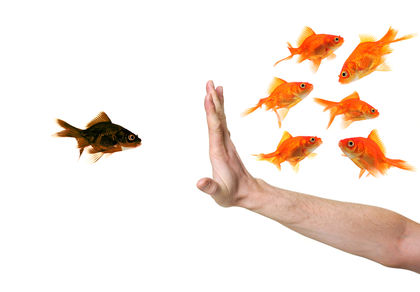

Discrimination, in an employment context, can be generally defined as treating an individual or group less well in recruiting, hiring, or any other terms and conditions of employment due to the person's or group's race, color, sex, religion, national origin, age, disability, or veteran's status. These categories are referred to as protected classifications because they are singled out for protection by equal employment opportunity (EEO) laws. Subcategories of people within each protected classification are referred to as protected groups. For example, male and female are the protected groups within the protected classification of sex. EEO legislation affords protection from illegal discrimination to all protected groups within a protected classification, not just the minority group. Thus, employment discrimination against a man is just as unlawful as that aimed at a woman. The lone exception to this rule concerns the use of affirmative action programs (discussed later), which, under certain circumstances, allow employers to treat members of certain protected groups preferentially.

In the U.S., effective federal legislation banning employment-related discrimination did not exist until the 1960s, when Congress passed Title VII of the Civil Rights Act (1964). In the years since, several other important federal laws have been passed. In addition to the myriad federal laws banning discrimination on the basis of race, color, sex, religion, national origin, age, disability, and veteran's status, almost all states have anti-discrimination laws affecting the workplace. Most of these laws extend the protections in federal law to employers that are not covered by the federal statutes because of their size (Title VII for example, applies only to employers with 15 or more employees). Some state laws also attempt to prevent discrimination against individuals and groups that are not included in federal law. For example, approximately 14 states have passed statutes protecting all workers in the states from employment discrimination based on sexual orientation and several others states prohibit public sector employers from discriminating on the basis of sexual orientation.

SPECIFIC ANTI-DISCRIMINATION

LEGISLATION AFFECTING

THE WORKPLACE

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act (CRA), passed in 1964, covers organizations that employ 15 or more workers for at least 20 weeks during the year. Specifically, the law states: "It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an employer to fail or refuse to hire or discharge any individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, because of such individual's race, color, religion, sex, or national origin." Interpretations of Title VII by courts have clarified the specific meaning of the prohibitions against discrimination. In general, it is safe to say that virtually any workplace decision involving personnel is subject to legal challenge on the basis of Title VII, including not only decisions made relative to recruiting and hiring, but also in relation to promotion, discipline, admission to training programs, layoffs, and performance appraisal. Harassment of applicants or employees because of their membership in a protected classification is also considered a violation of Title VII.

Title VII is probably the most valuable tool that employees have for remedying workplace discrimination because it covers the greatest number of protected classifications. If a court determines that discrimination has occurred, this law entitles the victim to relief in the form of legal costs and back pay (i.e., the salary the person would have been receiving had no discrimination occurred). For instance, suppose a woman sues a company for rejecting her application for a $35,000 per year construction job because the company unlawfully excludes women from this job. The litigation process takes two years and, ultimately, the court rules in the applicant's favor. To remedy this discrimination, the court could require the company to pay her legal fees and grant her $70,000 in back pay (two years' salary).

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 has had an enormous impact on the human resource management (HRM) practices of many companies, by forcing them to take a close look at the way they recruit, hire, promote, award pay raises, and discipline their employees. As a result of this self-scrutiny, many firms have changed their practices, making them more systematic and objective. For instance, most firms now require their supervisors to provide detailed documentation to justify the fairness of their disciplinary actions, and many firms are now more cautious with regard to their use of employment tests that restrict the employment opportunities for certain protected groups.

A number of Supreme Court decisions in the mid- to late 1980s made discrimination claims under Title VII more difficult for employees to substantiate. To put more teeth into the law, Congress amended it by enacting the Civil Rights Act of 1991. This 1991 amendment expanded the list of remedies that may be awarded in a discrimination case-the employer now has more to lose if found guilty of discrimination. In addition to legal fees and back pay, an employer may now be charged with punitive and compensatory damages (for future financial losses, emotional pain, suffering, inconvenience, mental anguish, and loss of enjoyment of life). The cap for these damages ranges from $50,000 to $300,000 depending on the size of the company. Employees are entitled to such damages in cases where discrimination practices are "engaged in with malice or reckless indifference to the legal rights of the aggrieved individual" (e.g., the employer is aware that serious violations are occurring, but does nothing to rectify them).

Moreover, the CRA of 1991 adds additional bite to the 1964 law by providing a more detailed description of the evidence needed to prove a discrimination claim, making such claims easier to prove. The CRA of 1991 also differs from the 1964 law by addressing the issue of mixed-motives cases. The CRA of 1991 states that mixed-motive decisions are unlawful. That is, a hiring practice is illegal when a candidate's protected group membership is a factor affecting an employment decision, even if other, more legitimate factors are also considered. For instance, a company rejects the application of a woman because she behaves in an "unlady-like" manner-she is "too aggressive for a woman, wears no makeup, and swears like a man." The company is concerned that she would offend its customers. The employer's motives are thus mixed: its concern about offending customers is a legitimate motive; its stereotyped view of how a "lady" should behave is a discriminatory one.

OTHER MAJOR EEO LAWS

The Equal Pay Act of 1963 prohibits discrimination in pay on the basis of sex when jobs within the same company are substantially the same. The company is allowed to pay workers doing the same job differently if the differences are based on merit, seniority, or any other reasonable basis other than the workers' gender.

The Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA) of 1967 bans employment discrimination on the basis of age by protecting applicants and employees who are 40 or older. The ADEA applies to nearly all employers of 20 or more employees. The ADEA protects only older individuals from discrimination; people under 40 are not protected. The act also prohibits employers from giving preference to individuals within the 40 or older group. For instance, an employer may not discriminate against a 50-year-old by giving preference to a 40-year-old. Except in limited circumstances, companies cannot require individuals to retire because of their age.

The Vocational Rehabilitation Act of 1973, a precursor to the 1990 passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, requires employers who are federal contractors ($2,500 or more) to take proactive measures to employ individuals with disabilities. This law is limited in application since it only applies to federal agencies and businesses doing contract work with the government.

The Vietnam Veterans' Readjustment Assistance Act, passed in 1974, requires employers who are government contractors ($10,000 or more) to take proactive steps to hire veterans of the Vietnam era. The scope of this law is also limited by the fact that only government contractors must comply.

The Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 amended the CRA of 1964 by broadening the interpretation of sex discrimination to include pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions. It prohibits discrimination against pregnant job applicants or against women who are of child-bearing age. It states that employees who are unable to perform their jobs because of a pregnancy-related condition must be treated in the same manner as employees who are temporarily disabled for other reasons. It has also been interpreted to mean that women cannot be prevented from competing for certain jobs within a company just because the jobs may involve exposure to substances thought harmful to the reproductive systems of women.

The Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986 prohibited discrimination based on national origin and citizenship. Specifically, the law states that employers of four or more employees cannot discriminate against any individual (other than an illegal alien) because of that person's national origin or citizenship status. In addition to being an anti-discrimination law, this act makes it unlawful to knowingly hire an unauthorized alien. At the time of hiring, an employer must require proof that the person offered the job is not an illegal alien.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 was designed to eliminate discrimination against individuals with disabilities. The employment implications of the act, which are delineated in Titles I (private sector) and II (public sector) of the ADA, affect nearly all organizations employing 15 or more workers. According to the act, an individual is considered disabled if he or she has a physical or mental impairment which substantially limits one or more of the individual's major life activities, such as walking, seeing, hearing, breathing, and learning, as well as the ability to secure or retain employment. In the years since passage of the legislation, the courts have applied a fairly broad definition of disability. The ADA only protects qualified individuals with a disability. To win a complaint, an individual who has been denied employment because of a disability must establish that, with accommodation (if necessary), he or she is qualified to perform the essential functions of the job in question. To defend successfully against such a suit, the employer must demonstrate that, even with reasonable accommodation, the candidate could not perform the job satisfactorily, or it must demonstrate that the accommodation would impose an undue hardship. The ADA defines "undue hardship" as those accommodations that require significant difficulty to effect or significant expense on the part of the employer.

An example of an ADA case would be one in which an employee is fired because of frequent absences caused by a particular disability. The employee may argue that the employer failed to offer a reasonable accommodation, such as a transfer to a part-time position. The employer, on the other hand, may argue that such an action would pose an undue hardship in that the creation of such a position would be too costly.

INTERPRETING EEO LAW

It is clear from the preceding discussion that an employer may not discriminate on the basis of an individual's protected group membership. But exactly how does one determine whether a particular act is discriminatory? Consider the following examples:

Case 1: A woman was denied employment as a police officer because she failed a strength test. During the past year that test screened out 90 percent of all female applicants and 30 percent of all male applicants.

Case 2: A woman was denied employment as a construction worker because she failed to meet the company's requirement that all workers be at least 5 feet 8 inches tall and weigh at least 160 pounds. During the past year, 20 percent of the male applicants and 70 percent of the female applicants have been rejected because of this requirement.

Case 3: A female accountant was fired despite satisfactory performance ratings. The boss claims she has violated company policy by moonlighting for another firm. The boss was heard making the comment, "Women don't belong in accounting, anyway."

Case 4: A male boss fired his female secretary because he thought she was too ugly, and replaced her with a woman who, in his opinion, was much prettier.

The Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1991 prohibit sex discrimination. Yet, knowing that sex discrimination is unlawful provides very little guidance in these cases. For instance, how important are the intentions of the employer? And how important are the outcomes of the employment decisions? In the first two cases, the employer's intentions seem to be noble, but the outcomes of the employment decisions were clearly disadvantageous to women. In the third case, the employer's intentions appear questionable, but the outcome may be fair. After all, the employee did violate the company policy. In the fourth case, the employer's intentions are despicable, yet the outcome did not adversely affect women in the sense that another member of her sex replaced the discharged employee.

To determine whether an EEO law has been violated, one must know how the courts define the term discrimination. In actuality, there are two definitions: disparate treatment and disparate impact. Disparate treatment is intentional discrimination. It is defined as treating people unfairly based on their membership in a protected group. For example, the firing of the female accountant in Case 3 would be an example of disparate treatment if the discharge were triggered by the supervisor's bias against female accountants (i.e., if men were not discharged for moonlighting). However, the employer's actions in Cases 1 and 2 would not be classified as disparate treatment because there was no apparent intent to discriminate.

While disparate treatment is often the result of an employer's bias or prejudice toward a particular group, it may also occur as the result of trying to protect the group members' interests. For instance, consider the employer who refuses to hire women for dangerous jobs in order to protect their safety. While its intentions might be noble, this employer would be just as guilty of discrimination as one with less noble intentions.

What about Case 4, where a secretary was fired for being too ugly? Is the employer guilty of sex discrimination? The answer is no if the bias displayed by the boss was directed at appearance, not sex. Appearance is not a protected classification. The answer is yes if the appearance standard were being applied only to women; that is, the company fired women but not men on the basis of their looks.

Disparate impact is unintentional discrimination, defined as any practice without business justification that has unequal consequences for people of different protected groups. This concept of illegal discrimination was first established by the Griggs v. Duke Supreme Court decision, handed down in 1971. Disparate impact discrimination occurs, for instance, if an arbitrary selection practice (e.g., an irrelevant employment test) resulted in the selection of a disproportionately low number of females or African Americans. The key notion here is "arbitrary selection practice." If the selection practice were relevant or job-related, rather than arbitrary, the employer's practice would be legal, regardless of its disproportionate outcome. For example, despite the fact the women received the short end of the stick in Cases 1 and 2, the employer's actions would be lawful if the selection criteria (e.g., the strength test and height and weight requirements) were deemed job related. As it turns out, strength tests are much more likely to be considered job related than height and weight requirements. Thus, the employer would probably win Case 1 and lose Case 2.

AFFIRMATIVE ACTION

The aim of affirmative action is to remedy past and current discrimination. Although the overall aim of affirmative action is thus identical to that of EEO (i.e., to advance the cause of protected groups by eliminating employment discrimination), the two approaches differ in the way they attempt to accomplish this aim. EEO initiatives are color-blind, while affirmative action initiatives are color-conscious. That is, affirmative action makes special provisions to recruit, train, retain, promote, or grant some other benefit to members of protected groups (e.g., women, blacks).

In some cases, employers are legally required to institute affirmative action programs. For instance, Executive Order 11246, issued by President Lyndon Johnson, makes such programs mandatory for all federal government contractors. Affirmative action can also be court ordered as part of a settlement in a discrimination case. For example, in the 1970s, the state of Alabama was ordered by the Supreme Court to select one black applicant for each white hired as a state trooper. The purpose of this decree was to rectify the effects of past discrimination that had been blatantly occurring for several years.

Most firms, however, are under no legal obligation to implement affirmative action programs. Those choosing to implement such programs do so voluntarily, believing it makes good business sense. These firms believe that by implementing affirmative action they can (1) attract and retain a larger and better pool of applicants, (2) avoid discrimination lawsuits, and (3) improve the firm's reputation within the community and its consumer base.

Affirmative action implementation consists of two steps. First, the organization conducts an analysis to identify the underutilized protected groups within its various job categories (e.g., officials and managers, professionals, service workers, sales workers). It then develops a remedial plan that targets these underutilized groups. A utilization analysis is a statistical procedure that compares the percentage of each protected group for each job category within the organization to that in the available labor market. If the organizational percentage is less than the labor-market percentage, the group is classified as being underutilized.

For example, the percentage of professionals within the organization who are women would be compared to the percentage of professionals in the available labor market who are women. The organization would classify women as being underutilized if it discovered, for instance, that women constitute 5 percent of the firm's professionals, and yet constitute 20 percent of the professionals in the available labor market.

The second step is to develop an affirmative action plan (AAP) that targets the underutilized protected groups. An AAP is a written statement that specifies how the organization plans to increase the utilization of targeted groups. The AAP consists of three elements: goals, timetables, and action steps.

An AAP goal specifies the percentage of protected group representation it seeks to reach. The timetable specifies the time period within which it hopes to reach its goal. For example, an AAP may state: "The firm plans to increase its percentage of female professionals from 5 to 20 percent within the next five years."

Exhibit 1

Affirmative Action Options

Always Legal

- Do nothing special, but make sure you always hire and promote people based solely on qualifications.

- Analyze workforce for underutilization.

- Set goals for increasing the percentage of minorities employed in jobs for which they are underutilized.

- Remove artificial barriers blocking the advancement of minorities.

- Create upward mobility training programs for minorities.

- Advertise job openings in a way that ensures minority awareness (e.g., contact the local chapter of NOW or the NAACP).

- Impose a rule that states that a manager cannot hire someone until there is a qualified minority in the applicant pool.

Sometimes Legal

(depends on the severity of the under-utilization problem)

- Impose a rule that when faced with two equally qualified applicants (a minority and non-minority), the manager must hire the minority candidate.

- Impose a rule that when faced with two qualified applicants (a minority and non-minority), hire the minority even if the other candidate has better qualifications.

- Set a hiring quota that specifies one minority hiring for every non-minority hiring.

Never Legal

- Do not consider any non-minorities for the position. Hire the most qualified minority applicant.

- Fire non-minority employee and replace him or her with a minority applicant.

The action steps specify how the organization plans to reach its goals and timetables. Action steps typically include such things as intensifying recruitment efforts, removing arbitrary selection standards, eliminating workplace prejudices, and offering employees better promotional and training opportunities. An example follows of a set of action steps:

- Meet with minority and female employees to request suggestions.

- Review present selection and promotion procedures to determine job-relatedness

- Design and implement a career counseling program for lower level employees to encourage and assist in planning occupational and career goals.

- Install a new, less subjective performance appraisal system.

When a company initiates an AAP as a remedy for under-utilization, it attempts to bring qualified women or minorities into the workplace to make it more reflective of the population from which the employees are drawn. This practice sometimes involves the use of preferential treatment or giving members of underutilized groups some advantage over others in the employment process. The use of preferential treatment has triggered a storm of controversy, as detractors point to the seemingly inherent lack of fairness in giving preference to one individual over another based solely on that person's race or gender. Supporters, however, believe that preferential treatment is sometimes needed to level the playing field. The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that preferential treatment is legal if engaged in as part of a bona fide affirmative action program that is designed to remedy underutilization. The AAP, however, must be temporary, flexible, and reasonable as noted in Exhibit 1.

SEE ALSO: Affirmative Action ; Employee Recruitment Planning ; Employee Screening and Selection ; Employment Law and Compliance

Lawrence S. Kleiman

Revised by Tim Barnett

FURTHER READING:

Barnett, T., A. McMillan, and W. McVea. "Employer Liability for Harassment by Supervisors: An Overview of the 1999 EEOC Guidelines." Journal of Employment Discrimination Law 2, no. 4 (2000): 311–315.

Barnett, T. and W. McVea. "Preemployment Questions Under the Americans with Disabilities Act." SAM Advanced Management Journal 62 (1997): 23–27.

Clark, M. M. "Religion vs. Sexual Orientation." HR Magazine 49, no. 8 (2004): 54–59.

Dessler, G. Human Resource Management. 10th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 2005.

Kleiman, L.S. Human Resource Management: A Tool for Competitive Advantage. Cincinnati: South-Western College Publishing, 2000.

Kleiman, L.S., and R.H. Faley. "Voluntary Affirmative Action and Preferential Treatment: Legal and Research Implications." Personnel Psychology 77, no. 1 (1988): 481–496.

Smith, M.A., and C. Charles. "Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964." Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law 5, no. 1 (2004): 421–476.

Wolkinson, B.W., and R.N. Block. Employment Law. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1996.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: