NONPROFIT ORGANIZATIONS

In the United States, nonprofit organizations (NPOs) are organizations that qualify for tax-exempt status under the U.S. Internal Revenue Code. About half are public charities, to which donors can deduct contributions from their taxes. Private foundations also are charitable organizations, but they are not public charities. They exist primarily to fund charities or individuals. Other types of tax exempt organizations include social welfare, labor or agricultural organizations, business leagues, and fraternal beneficiary societies. Nonprofit organizations are not prohibited from earning a profit or paying salaries and wages, but they must devote any surplus to the organization.

Nonprofit organizations also are known as not-for-profit organizations, or as the "independent sector," as opposed to business or government. Nonprofits constitute about 10 percent of U.S. employees. These organizations play a unique role in society, falling between the concepts of public and private entities. Public agencies provide goods and services that are considered to be universally desirable (such as national security or infrastructure). Private enterprises serve individual tastes and preferences and depend on market-based competition to prosper. By contrast, nonprofit organizations supply services that are considered good for the community as a whole or for specific community members, but which do not elicit widespread taxpayer support for direct provision. The distinction may be characterized as the difference between "it is right" that these services should exist, and the idea all members of society "have a right" to such services.

While the nonprofit organization exists in many countries, the focus here is on the American NPO. The primary factors unique to this American sector are volunteers, contributions, and tax-exempt status.

THE ROLE OF NONPROFITS

IN THE AMERICAN ECONOMY

Nonprofit organizations play a large role in the American economy. It is difficult to get an accurate count of nonprofits, because only organizations with more than $5,000 in annual gross receipts must register with the IRS and only those with receipts in excess of $25,000 must file with the IRS. According to the National Center for Charitable Statistics (NCCS), in 2001 there were 1.33 million tax exempt organizations in the United States. This figure includes those registered and filing with the IRS. Of these, 783,436 were registered charitable nonprofits, including 264,674 that filed with the IRS and 56,582 that were foundations. Human services organizations make up more than 30 percent of the charitable nonprofits; education is the second largest field with 17 percent, and health-care/mental health is the third with 13 percent. The remaining nonprofit organizations (486,295) fall under the areas of social welfare, labor/agriculture, business leagues, and other. While hospitals represented less than 2 percent of the reporting charitable nonprofits, they had 41 percent of the total expenditures.

It is estimated that there are twice as many organizations not required to file with the IRS because they did not take in $5,000 annually. This would include such familiar organizations as PTAs and Little Leagues. No statistics are available regarding these organizations.

The NCCS collects and disseminates statistics on the U.S. nonprofit sector. This data is gathered from the IRS and other government agencies, private sector service organizations, and the scholarly community. The NCCS builds compatible national, state, and regional databases and develops uniform standards for reporting on the activities of charitable organizations. Excellent charts representing these data are presented in The United States Nonprofit Sector 2001, which is available from The National Council of Nonprofit Associations.

In 2004 nonprofit organizations contributed about 5 percent of the gross domestic product. In 2001 more than 12.5 million people were actively involved in NPO activity, representing approximately 9.5 percent of total U.S. employment. Employment in the nonprofit sector is growing more rapidly than in the business sector; 2.5 percent versus 1.8 percent. The number of Americans employed in the nonprofit sector has doubled in the last 25 years. According to the Council of Foundations, the average annual turnover rate for associations is 24 percent, but there appears to be wide variation among nonprofit subsectors. For example, employee turnover in child welfare agencies shows rates between 100 percent and 300 percent.

The nonprofit sector relies heavily on volunteers, which can be a problem for nonprofit managers. Volunteers are motivated to support a particular cause, and not by pay and benefits. Thus, managers must provide creative incentives in "psychic income," such as recognition. In addition, attendance may be sporadic, leading to variable levels of capacity at any given time. Some organizations in this sector exist primarily to supply employment to those who have traditionally been considered unemployable, with the goal of boosting both morale and self-sufficiency.

FINANCIAL INFORMATION

To generate revenue, NPOs rely on direct appeal to those individuals, corporations, and other entities that value the underlying cause represented by the organization. Fundraising events, including door-to-door appeals and mass mailings, are highly visible means of garnering funds. Charitable nonprofits had about $822 billion in expenditures in 2001, representing approximately 8 percent of the Gross Domestic Product. This revenue came primarily from fees, government grants and contracts, and investments. About 14 percent came from contributions. Competition for funds is more complex than in the corporate world, as there is no financial reward for the contributor. Each year, the American Association of Fundraising Counsel (AAFRC) publishes national giving estimates in its Giving USA report. For 2000, Giving USA reported the following national totals:

- Individuals: $152.07 billion (75.0%)

- Foundations: $24.50 billion (12.0%)

- Bequests: $16.02 billion (7.8%)

- Corporations: $10.86 billion (5.3%)

Some organizations rely heavily on competitive grants from governmental or philanthropic institutions. Nationally generated funds may be redistributed to local communities on the basis of need, as is done by the United Way and the Red Cross. Increasingly, non-profits have relied on participant dues, fees, or charges. Such charges can range from the minimal "suggested contribution" for a senior center lunch to the bill for costly medical procedures at a major hospital.

Of the reporting charitable nonprofit institutions in 2001, hospitals had the greatest percentage of total sector assets (about 30 percent), followed by higher education with approximately 20 percent. Human services, healthcare (excluding hospitals), and lower education, each had about 10 percent. Interestingly, only 6.5 percent of the reporting charitable nonprofits had annual expenditures greater than $5 million. However, these organizations accounted for more than 82 percent of total assets and more than 87 percent of total expenditures.

The accuracy of financial information about this sector of the economy is limited. First, the ongoing initiative to collect and computerize data in standardized form began in the late 1980s to early 1990s. While the Bureau of Labor Statistics tabulates employment figures, the financial information lags due to attempts to standardize and code the data. Second, while all tax-exempt organizations must apply for such status, only those with total annual revenues of at least $25,000 are required to file a Form 990 with the Internal Revenue Service. These non-filers represent about two-thirds of all registered non-profit organizations. Third, churches are not required to file a Form 990, leaving this data estimation to private sources. Fourth, pass-through contributions (for example, revenues to both the United Way and the local charities it supports) may be double-counted. Therefore, financial figures are at best an estimate.

There is no single agency with oversight for non-profit organizations. The IRS serves as one control, but some states have instituted more rigorous guidelines than those at the federal level. The Financial Accounting Standards Board, a private self-regulatory body for the accounting profession, developed Financial Accounting Standards 116 and 117 covering nonprofits, but these prescriptions allow a different form of generally accepted accounting practices (GAAP) from private organizations with similar functions. The BBB Wise Giving Alliance collects and distributes information on national nonprofit organizations. It routinely asks such organizations for information about their programs, governance, fund-raising practices, and finances. Although The BBB Wise Giving Alliance does not recommend charities, it does select charities for evaluation based on the volume of donor inquiries about individual organizations. The BBB Wise Giving Alliance was formed in 2001 with the merger of the National Charities Information Bureau and the Council of Better Business Bureaus Foundation and its Philanthropic Advisory Service. The BBB Wise Giving Alliance is a nonprofit charitable organization, affiliated with the Council of Better Business Bureaus.

TAX-EXEMPT STATUS

In exchange for the supply of quasi-public goods and services, nonprofit organizations are exempt from federal taxation on the excess of revenues over costs within the fiscal year. This practice was established in 1913 with the passage of the first federal income tax law. In addition, they also may be forgiven state and local property taxes, and may receive discount postal privileges. Thus, these organizations are publicly subsidized while not directly supported by all taxpayers.

To qualify for tax-exempt status, the nonprofit organization must satisfy a variety of prerequisites. Among these is the declaration of a primary purpose or cause that qualifies under the Internal Revenue Service code. There is no ownership of assets or income other than that of the organization itself. Externally, this implies that there is no income distribution in the form of dividends or other such payments. Internally, there is the further requirement that the organization does not exist for the benefit of individual employees or board members; payment to such individuals in the form of salary, rent, or contractual arrangement is scrutinized by the IRS. However, the only available penalty is the withdrawal of tax-exempt status, and the IRS has historically delivered this blow only rarely.

Examples of nonprofit organizations include such well-known giants as the United Way, the Red Cross, and the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts. At the other end of the spectrum are local volunteer fire departments, churches, crisis intervention centers, and civic centers. Many hospitals and universities function as nonprofit institutions.

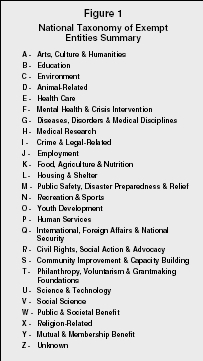

Figure 1 lists the full range of categories of American NPOs as defined by the National Taxonomy

National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities Summary

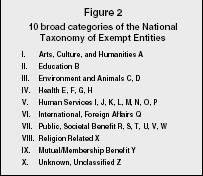

10 broad categories of the National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities

From 1940 to the early 1990s, human services and health accounted for approximately half of the NPOs in the United States. In some NPOs, benefits are limited to a select group, such as senior citizens (local agencies on aging) or those suffering from a specific disease (the American Cancer Society). Other groups have relatively open membership for those willing to pay the fee; an example is the YMCA, which provides recreational facilities.

CHALLENGES FOR NONPROFIT

MANAGEMENT

Management must contend with the unique aspects of nonprofit organizations: volunteer labor, solicited contributions, and maintaining tax-exempt status. In addition, Herzlinger suggests that NPOs are highly antithetical to business in other important ways: they lack ownership, competition, and the profit motive. Without these incentives, it may be difficult to maintain effectiveness and efficiency. Even measurement of customer satisfaction may prove elusive, as customers may have no alternatives against which to compare the services received. Some controversy exists over several aspects of nonprofit organizations:

-

For example, some question the rationale of the tax-exempt status of

open-membership

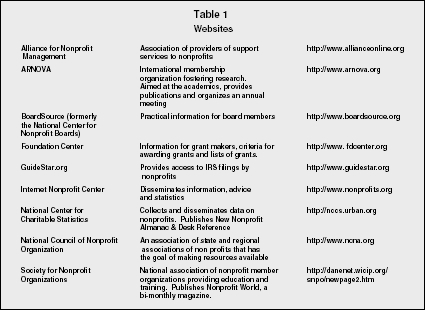

Table 1

Table 1

Websites

facilities, such as the YMCA. For-profit providers of similar services submit that the subsidy of NPOs diminishes the for-profit organization's ability to compete. This situation has led to as yet unsuccessful legislative attempts to level the playing field.Alliance for Nonprofit Management Association of providers of support services to nonprofits http://www.allianceonline.org ARNOVA International membership organization fostering research. Aimed at the academics, provides publications and organizes an annual meeting http://www.arnova.org BoardSource (formerly the National Center for Nonprofit Boards) Practical information for board members http://www.boardsource.org Foundation Center Information for grant makers, criteria for awarding grants and lists of grants. http://www.fdcenter.org GuideStar.org Provides access to IRS filings by nonprofits http://www.guidestar.org Internet Nonprofit Center Disseminates information, advice and statistics http://www.nonprofits.org National Center for Charitable Statistics Collects and disseminates data on nonprofits. Publishes New Nonprofit Almanac & Desk Reference http://nccs.urban.org National Council of Nonprofit Organization An association of state and regional associations of non profits that has the goal of making resources available http://www.ncna.org Society for Nonprofit Organizations National association of nonprofit member organizations providing education and training. Publishes Nonprofit World, a bi-monthly magazine. http://danenet.wicip.org/snpo/newpage2.htm - Some people question how much nonprofits spend on programs. The BBB Wise Giving Alliance (a nonprofit organization itself) recommends that nonprofits spend at least 50 percent on program activity. Other organizations set this level as high as 80 percent. The remainder is to be spent on nonprogram expenses, such as administrative and fundraising costs. The amount spent on fundraising can vary widely based upon whether the nonprofit is new or established with many donors. However, no regulation exists to ensure that the majority of revenues are spent on the cause for which the funds were collected.

- Others question how nonprofits are regulated, and who regulates them. State agencies are increasingly requiring reports from active NPOs to monitor fundraising activity; the agency in turn responds to individual inquiries about the NPO's self-reported record. As in the corporate and governmental groups, administrative salaries occasionally make the news, encouraging contributors to reconsider how their contributions are being used.

Nonprofit organizations are a valuable part of the economy in America and many other countries, providing a broad range of services that might not otherwise be affordable or available without the subsidy of tax exemption. As NPOs grow in number and scope, there is increasing pressure to report on financial activity and performance fulfillment in this sector. The future of nonprofits may rely on disclosure and accountability.

SEE ALSO: Balance Sheets ; Financial Issues for Managers ; Income Statements

Karen L. Brown

Revised by Judith M. Nixon

FURTHER READING:

BBB Wise Giving Alliance. "BBB Wise Giving Alliance." Available from < http://Give.org >

Council of Economic Advisors. 2005 Economic Report of the President. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2005. Available from < http://www.gpoaccess.gov/eop/ >

Herzlinger, R.E. "Can Public Trust in Nonprofits and Governments be Restored?" Harvard Business Review 74, no. 2 (1996): 97–107.

Langer, Stephen. "How Much Are You Really Worth? Here's the Latest on Nonprofit Salaries." Nonprofit World 23, no. 1 (2005): 27.

Lewis, Robert L. Effective Nonprofit Management: Essential Lessons for Executive Directors. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers, 2001.

The National Center for Charitable Statistics at the Urban Institute. "Number of Nonprofit Organizations in the United States 1996–2004." Available from < http://nccsdataweb.urban.org/PubApps/profile1.php?state=US >

National Council of Nonprofit Associations, and The National Center for Charitable Statistics at the Urban Institute. "The United States Nonprofit Sector 2001." Available from < http://www.ncna.org/_uploads/documents/live//us.nonprofit.sector.report.pdf >

The New Nonprofit Almanac & Desk Reference. Washington, D.C.: Independent Sector/Urban Institute, 2002.

The Non-Profit Sector in a Changing Economy. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2003.

Pidgeon, Walter P. The Not-for-Profit CEO: How to Attain and Retain the Corner Office. New York: John Wiley, 2004.

Taylor, Barbara E., Richard P. Chait, and Thomas P. Holland. "The New Work of the Nonprofit Board." Harvard Business Review 74, no. 5 (1996): 36–46.

White, Gary W. "Nonprofit Organizations." Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship 9, no. 1 (2003): 49–80.

——. "Nonprofit Organizations Part II." Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship 10, no. 1 (2004): 63–79.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: