STRATEGY IMPLEMENTATION

A key role of a CEO's is to communicate a vision and to guide strategic planning. Those who have successfully implemented strategic plans have often reported that involving teams at all levels in strategic planning helps to build a shared vision, and increases each individual's motivation to see plans succeed.

Clarity and consistent communication, from mapping desired outcomes to designing performance measures, seem to be essential to success. Successful leaders have often engaged their teams by simply telling the story of their shared vision, and publicly celebrating large and small wins, such as the achievement of milestones. To ensure that the vision is shared, teams need to know that they can test the theory, voice opinions, challenge premises, and suggest alternatives without fear of reprimand.

Implementing strategic plans may require leaders who lead through inspiration and coaching rather than command and control. Recognizing and rewarding success, inspiring, and modeling behaviors is more likely to result in true commitment than use of authority, which can lead to passive resistance and hidden rebellion.

CREATING STRATEGIC PLANS

The senior management team must come together to review, discuss, challenge, and finally agree on the strategic direction and key components of the plan. Without genuine commitment from the senior team, successful implementation is unlikely.

Strategic group members must challenge themselves to be clear in their purpose and intent, and to push for consistent operational definitions that each member of the team agrees to. This prevents differing perceptions or turf-driven viewpoints later on. A carefully chosen, neutral facilitator can be essential in helping the team to overcome process, group dynamics, and interpersonal issues.

A common way to begin is to review the organization's current state and future possibilities using a SWOT (strength, weakness, opportunity, and threat) analysis. This involves identifying strengths and core capabilities in products, resources, people, and customers. These are what the organization is best at, and why it is in business. Many organizations have responded to this review by spinning off ventures that were not related to their core business. For example, Chrysler sold its interests in Maserati, Lambourghini, and Diamond Star and then concentrated on developing "great cars, great trucks." This sent a clear message to employees and other stakeholders, and triggered the company's renaissance.

Using SWOT, once strengths and core capabilities are defined the next step is to identify weaknesses or vulnerabilities. This is usually the most difficult for organizations and leaders to assess. The identification of gaps is often threatening. In some organizations it is not considered safe to admit to weakness; but an honest appraisal can make the difference between success and failure. Again, reviews should include a look at products, services, resources, customers, and employees. Do the right skills exist in the current staff? Are there enough resources to invest in areas of critical need? Are the appropriate systems and structures in place to support the needs of the team? Does the culture reinforce and connect with the mission and vision of the organization?

Now the review moves to the external environment. What opportunities exist for development and growth? Do these opportunities correspond to the organization's strengths? What are the critical changes the market faces over the next one, three, and five years? How well is the organization positioned for the anticipated market changes? Additional points for debate include the greatest innovation or change that needs to occur for the organization to be successful, and the values that will drive these changes.

Next, using the SWOT assessment process, threats in the current and future market are identified. How is the competition positioned relative to the opportunities for growth that have been identified, and how are they positioned relative to the organization's strengths and weaknesses?

With this information, organizations can finalize their strategy by defining the vision, creating a mission statement, and identifying their competitive advantages. The communication of the strategy will require a clear, consistent message. It is an ideal time for the leadership to operationally define each critical area of the plan to ensure agreement and commitment. Key stakeholders should be included in the process. Soliciting their input is often a valuable aide in implementation.

Finally, organizations should review each of the gaps that have been identified. Do the necessary resources exist to invest in shoring up the gaps? Are these resources allocated properly? It is usually not possible to address all of the gaps at once. Organizations should create a priority list for action so plans are realistic and focused on the greatest areas of need. These priorities will become a key focus of implementing the plan.

Once the senior leadership team has completed the top-level strategy, the next step is to break that overall goal down into functional areas or core strategies. Typically this will include service/operations management, technology management, product management, supplier management, people management, and financial management, or some variation on these areas. Each identifies how they contribute to achieving the overall strategic plan. They can model the steps taken by the senior team and conduct a SWOT analysis from their vantage point. Once the core strategies are defined, the senior team must ensure that the overall strategy will be achieved; that is, that the sum of the parts (functional strategies) will add up to the whole (overall strategy).

Strategy communication continues to be critical, so operational definitions should not be overlooked. Each functional area should create their own definitions to ensure agreement and commitment. A common source of problems in implementation is that divergent functional perspectives may not be aligned with the overall strategy. Unless these issues are addressed, each area may interpret the plan with a lens of "How does my area win?" rather than "How does the organization win?"

Key stakeholders can be engaged in different ways. Aside from events, publicity, and personification of the vision and strategy by key leaders, stakeholders can be engaged by soliciting their input on the current state of the organization and the vision (similar to the SWOT analysis described earlier). Involving stakeholders in this manner should be done seriously, with an intent to use their distinct perspectives; this can add to the soundness of the analysis. Asking for opinions and then ignoring them can arouse distrust and resentment.

As the strategic plan and performance measures are being created, the organization must make sure that they are aligned with the systems, structure, culture, and performance management architecture. The best plans may fail because the reward systems motivate different behaviors than those called for in the strategy map and measurement design. For example, if a team approach to business development is outlined in the plan, but sales commission remains individual, organizations will be hard pressed to see a team focus.

The career development, performance management and reward systems must be reviewed to ensure linkage to and support of the strategic intent. Many organizations have found they needed to link their strategic plan to their internal systems and structures to ensure overall alignment and to avoid confusion.

IMPLEMENTING STRATEGIC PLANS

Once strategies have been agreed on, the next step is implementation; this is where most failures occur. It is not uncommon for strategic plans to be drawn up annually, and to have no impact on the organization as a whole.

A common method of implementation is hoopla-a total communication effort. This can involve slogans, posters, events, memos, videos, Web sites, etc. A critical success factor is whether the entire senior team appears to buy into the strategy, and models appropriate behaviors. Success appears to be more likely if the CEO, or a very visible leader, is also a champion of the strategy.

Strategic measurement can help in implementing the strategic plan. Appropriate measures show the strategy is important to the leaders, provide motivation, and allow for follow-through and sustained attention. By acting as operational definitions of the plan, measures can increase the focus of the strategy, aligning the workforce around specific issues. The results can include faster changes (both in strategic implementation, and in everyday work); greater accountability (since responsibilities are clarified by strategic measurement, people are naturally more accountable); and better communication of responsibilities (because the measures show what each group's primary responsibility is), which may reduce duplication of effort.

Creating a strategic map (or causal business model) helps identify focal points; it shows the theory of the business in easily understood terms, showing the cause and effect linkages between key components. It can be a focal point for communicating the vision and mission, and the plan for achieving desired goals. If tested through statistical-linkage analysis, the map also allows the organization to leverage resources on the primary drivers of success.

The senior team can create a strategic map (or theory of the business) by identifying and mapping the critical few ingredients that will drive overall performance. This can be tested (sometimes immediately, with existing data) through a variety of statistical techniques; regression analysis is frequently used, because it is fairly robust and requires relatively small data sets.

This map can lead to an instrument panel covering a few areas that are of critical importance. The panel does not include all of the areas an organization measures, rather the few that the top team can use to guide decisions, knowing that greater detail is available if they need to drill down for more intense examination. These critical few are typically within six strategic performance areas: financial, customer/market, operations, environment (which includes key stakeholders), people, and partners/suppliers. Each area may have three or four focal points; for example, the people category may include leadership, common values, and innovation.

Once the strategic map is defined, organizations must create measures for each focal point. The first step is to create these measures at an organizational level. Once these are defined, each functional area should identify how they contribute to the overall measures, and then define measures of their own. Ideally, this process cascades downward through the organization until each individual is linked with the strategy and understands the goals and outcomes they are responsible for and how their individual success will be measured and rewarded.

Good performance measures identify the critical focus points for an organization, and reward their successful achievement. When used to guide an organization, performance measures can be a competitive advantage because they drive alignment and common purpose across an organization, focusing everyone's best efforts at the desired goal. But defining measures can be tricky. Teams must continue to ask themselves, "If we were to measure performance this way, what behavior would that motivate?" For example, if the desired outcome is world-class customer service, measuring the volume of calls handled by representatives could drive the opposite behavior.

CASCADING THE PLAN

In larger organizations, cascading the strategic plan and associated measures can be essential to everyday implementation. To a degree, hoopla, celebrations, events, and so on can drive down the message, but in many organizations, particularly those without extremely charismatic leaders, this is not sufficient.

Cascading is often where the implementation breaks down. For example, only sixteen percent of the respondents in a 1999 Metrus Group survey believed that associates at all levels of their company could describe the strategy. In a 1998 national survey of Quality Progress readers, cascading was often noted as being a serious problem in implementing strategic measurement systems.

Organizations have found it to be helpful to ask each functional area to identify how they contribute to achieving the overall strategic plan ("functional area" designating whatever natural units exist in the organization-functions, geographies, business units, etc.). Armed with the strategic map, operational definitions and the overall organizational strategic performance measures, each functional area creates their own map of success and defines their own specific performance measures. They can follow the model outlined above starting with their own SWOT analysis.

For example, in the 1990s, Sears cascaded its strategic plan to all of its stores through local store strategy sessions involving all employees. The plan was shown graphically by a strategy map, and reinforced through actions such as the sale of financial businesses such as Allstate. Online performance measures helped store managers to gain feedback on their own performance, and also let them share best practices with other managers.

Functional area leaders may be more successful using a cascade team to add input and take the message forward to others in the area. Developing ambassadors or process champions throughout the organization to support and promote the plan and its implementation can also enhance the chances of success. These champions may be candidates for participation on the design or cascade teams, and should be involved in the stakeholder review process.

EXTERNAL CONSULTANTS

External consultants can play an important role in building and implementing strategic plans if they are used appropriately. Rather than creating or guiding an organization's strategy, the primary role of a consultant should be that of a facilitator, a source of outside perspective, and perhaps as a resource for guiding the process itself. This allows each member of the internal team to participate fully without having to manage the agenda and keep the team focused on the task at hand. Consultants can keep the forum on track by directing the discussion to ensure objective, strategic thinking around key issues, tapping everyone's knowledge and expertise, raising pertinent questions for discussion and debate, managing conflict, and handling group-think and other group dynamics issues.

Consultants can extract the best thinking from the group, and ensure that the vision and mission are based on a sound, critical review of the current state and anticipated future opportunities. Once this is accomplished, consultants can facilitate the identification of desired outcomes and the drivers needed to achieve them. They can also help to assure that a true consensus is actually reached, rather than an appearance of a consensus due to fear, conformity, or other group effects.

During the cascading phase, consultants can help to avoid failure by facilitating the linkage from the over-arching corporate strategy, through the departmental and or functional level to the team and individual level. This is a point where turf interests can invade the thought process, coloring local measurement design to ensure local rewards. This may not align with the overall strategic intent, so care must be taken to continually link back to the over-arching vision of the organization.

Building and implementing winning strategic plans is a continuous journey, requiring routine reviews and refinement of the measures and the strategic plans themselves. By partnering with internal teams, stakeholders and trusted external consultants, leaders can develop better strategic plans and implement them more successfully.

STRATEGY IMPLEMENTATION ISSUES

Strategy implementation almost always involves the introduction of change to an organization. Managers may spend months, even years, evaluating alternatives and selecting a strategy. Frequently this strategy is then announced to the organization with the expectation that organization members will automatically see why the alternative is the best one and will begin immediate implementation. When a strategic change is poorly introduced, managers may actually spend more time implementing changes resulting from the new strategy than was spent in selecting it. Strategy implementation involves both macro-organizational issues (e.g., technology, reward systems, decision processes, and structure), and micro-organizational issues (e.g., organization culture and resistance to change).

MACRO-ORGANIZATIONAL ISSUES

OF STRATEGY IMPLEMENTATION

Macro-organizational issues are large-scale, system-wide issues that affect many people within the organization. Galbraith and Kazanjian argue that there are several major internal subsystems of the organization that must be coordinated to successfully implement a new organization strategy. These subsystems include technology, reward systems, decision processes, and structure. As with any system, the subsystems are interrelated, and changing one may impact others.

Technology can be defined as the knowledge, tools, equipment, and work methods used by an organization in providing its goods and services. The technology employed must fit the selected strategy for it to be successfully implemented. Companies planning to differentiate their product on the basis of quality must take steps to assure that the technology is in place to produce superior quality products or services. This may entail tighter quality control or state-of-the-art equipment. Firms pursuing a low-cost strategy may take steps to automate as a means of reducing labor costs. Similarly, they might use older equipment to minimize the immediate expenditure of funds for new equipment.

Reward systems or incentive plans include bonuses and other financial incentives, recognition, and other intangible rewards such as feelings of accomplishment and challenge. Reward systems can be effective tools for motivating individuals to support strategy implementation efforts. Commonly used reward systems include stock options, salary raises, promotions, praise, recognition, increased job autonomy, and awards based on successful strategy implementation. These rewards can be made available only to managers or spread among employees throughout the organization. Profit sharing and gain sharing are sometimes used at divisional or departmental levels to more closely link the rewards to performance.

Questions and problems will undoubtedly occur as part of implementation. Decisions pertaining to resource allocations, job responsibilities, and priorities are just some of the decisions that cannot be completely planned until implementation begins. Decision processes help the organization make mid-course adjustments to keep the implementation on target.

Organizational structure is the formal pattern of interactions and coordination developed to link individuals to their jobs and jobs to departments. It also involves the interactions between individuals and departments within the organization. Current research supports the idea that strategies may be more successful when supported with structure consistent with the new strategic direction. For example, departmentalizations on the basis of customers will likely help implement the development and marketing of new products that appeal to a specific customer segment and could be particularly useful in implementing a strategy of differentiation or focus. A functional organizational structure tends to have lower overhead and allows for more efficient utilization of specialists, and might be more consistent with a low-cost strategy.

MICRO-ORGANIZATIONAL ISSUES OF

STRATEGY IMPLEMENTATION

Micro-organizational issues pertain to the behavior of individuals within the organization and how individual actors in the larger organization will view strategy implementation. Implementation can be studied by looking at the impact organization culture and resistance to change has on employee acceptance and motivation to implement the new strategy.

Peters and Waterman focused attention on the role of culture in strategic management. Organizational culture is more than emotional rhetoric; the culture of an organization develops over a period of time is influenced by the values, actions and, beliefs of individuals at all levels of the organization.

Persons involved in choosing a strategy often have access to volumes of information and research reports about the need for change in strategies. They also have time to analyze and evaluate this information. What many managers fail to realize is that the information that may make one strategic alternative an obvious choice is not readily available to the individual employees who will be involved in the day-to-day implementation of the chosen strategy. These employees are often comfortable with the old way of doing things and see no need to change. The result is that management sees the employee as resisting change.

Employees generally do not regard their response to change as either positive or negative. An employee's response to change is simply behavior that makes sense from the employee's perspective. Managers need to look beyond what they see as resistance and attempt to understand the employee's frame of reference and why they may see the change as undesirable.

FORCE FIELD ANALYSIS

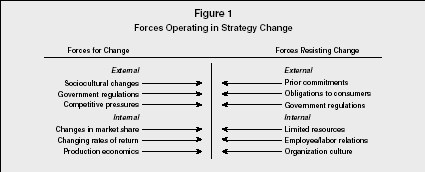

One technique for evaluating forces operating in a change situation is force field analysis. This technique uses a concept from physics to examine the forces for and against change. The length of each arrow as shown in Figure 1 represents the relative strength of each force for and against change. An equilibrium point is reached when the sum of each set of forces is equal. Movement requires that forces for the change exceed forces resisting the change. Reducing resisting forces is usually seen as preferable to increasing supporting forces, as the former will likely reduce tension and the degree of conflict.

This model is useful for identifying and evaluating the relative power of forces for and against change. It is a useful way of visualizing salient forces and may allow management to better assess the probable direction and speed of movement in implementing new strategies. Forces for change can come from outside the organization or from within. External forces for change may result from sociocultural factors, government regulations, international developments, technological changes, and entry or exit of competitors. Internal forces for change come from within the organization and may include changes in market share, rising production costs, changing financial conditions, new product development, and so on.

Similarly, forces resisting change may result from external or internal sources. Common external pressures opposing change are contractual commitments to other businesses (suppliers, union), obligations to customers and investors, and government regulations of the firm or industry. Internal forces resisting change are usually abundant; limited organizational resources (money, equipment, personnel) is usually one of the first reasons offered as to why change cannot be implemented. Labor agreements limit the ability of management to transfer and, sometimes, terminate employees. Organization culture may also limit the ability of a firm to change strategy. As the experience at Levi Strauss & Co. suggests, it is often hard to convince employees of the need for change when their peers and other members of the organization are not supportive of the proposed change.

The total elimination of resistance to change is unlikely because there will almost always remain some uncertainty associated with a change. Techniques that have the potential to reduce resistance to change when

Forces Operating in Strategy Change

Participation is probably the most universally recommended technique for reducing resistance to change. Allowing affected employees to participate in both the planning and implementation of change can contribute to greater identification with the need for and understanding of the goals of the new strategy. Participation in implementation also helps to counteract the disruption in communication flows, which often accompanies implementation of a change. But participation has sometimes been overused. Participation does not guarantee acceptance of the new strategy, and employees do not always want to participate. Furthermore, participation is often time consuming and can take too long when rapid change is needed.

Another way to overcome resistance to implementing a new strategy is to educate employees about the strategy both before and during implementation. Education involves supplying people with information required to understand the need for change. Education can also be used to make the organization more receptive to the need for the change. Furthermore, information provided during the implementation of a change can be used to build support for a strategy that is succeeding or to redirect efforts in implementing a strategy that is not meeting expectations.

Group pressure is based on the assumption that individual attitudes are the result of a social matrix of co-workers, friends, family, and other reference groups. Thus, a group may be able to persuade reluctant individuals to support a new strategy. Group members also may serve as a support system aiding others when problems are encountered during implementation. However, the use of a group to introduce change requires that the group be supportive of the change. A cohesive group that is opposed to the change limits the ability of management to persuade employees that a new strategy is desirable.

Management can take steps employees will view as being supportive during the implementation of a change. Management may extend the employees time to gradually accept the idea of change, alter behavior patterns, and learn new skills. Support might also take the form of new training programs, or simply providing an outlet for discussing employee concerns.

Negotiation is useful if a few important resistors can be identified, perhaps through force field analysis. It may be possible to offer incentives to resistors to gain their support. Early retirement is frequently used to speed implementation when resistance is coming from employees nearing retirement age.

Co-optation is similar to negotiation in that a leader or key resistor is given an important role in the implementation in exchange for supporting a change. Manipulation involves the selective use of information or events to influence others. Such techniques may be relatively quick and inexpensive; however, employees who feel they were tricked into not resisting, not treated equitably, or misled may be highly resistant to subsequent change efforts. Distrust of management is often the result of previous manipulation.

Coercion is often used to overcome resistance. It may be explicit (resistance may be met with termination) or implicit (resistance may influence a promotion decision). Coercion may also result in the removal of resistors through either transfer or termination. Coercion often leads to resentment and increased conflict. However, when quick implementation of a change is needed or when a change will be unpopular regardless of how it is implemented, some managers feel coercion may be as good as most alternatives and faster than many others.

ROLE OF TOP MANAGEMENT

Top management is essential to the effective implementation of strategic change. Top management provides a role model for other managers to use in assessing the salient environmental variables, their relationship to the organization, and the appropriateness of the organization's response to these variables. Top management also shapes the perceived relationships among organization components.

Top management is largely responsible for the determination of organization structure (e.g., information flow, decision-making processes, and job assignments). Management must also recognize the existing organization culture and learn to work within or change its parameters. Top management is also responsible for the design and control of the organization's reward and incentive systems.

Finally, top management are involved in the design of information systems for the organization. In this role, managers influence the environmental variables most likely to receive attention in the organization. They must also make certain that information concerning these key variables is available to affected managers. Top-level managers must also provide accurate and timely feedback concerning the organization's performance and the performance of individual business units within the organization. Organization members need information to maintain a realistic view of their performance, the performance of the organization, and the organization's relationship to the environment.

SEE ALSO: Strategic Planning Failure ; Strategic Planning Tools ; Strategy Formulation ; Strategy in the Global Environment ; Strategy Levels

Carolyn Ott ,

David A. KZatz , and

Joe G. Thomas

Revised by Gerhard Plenert

FURTHER READING:

Anthanassiou, N., and D. Nigh. "The Impact of U.S. Company Internationalization on Top Management Team Advice Networks." Strategic Management Journal, January 1999, 83–92.

Galbraith, J., and R. Kazanjian. Strategy Implementation: Structure, Systems and Process. 2nd ed. St. Paul, MN: West, 1986.

Harris, L. "Initiating Planning: The Problem of Entrenched Cultural Values." Long Range Planning 32, no. 1 (1999): 117–126.

Heskitt, J.L., W.E. Sasser, Jr., and L.A. Schlesinger. The Service Profit Chain. New York: The Free Press, 1997.

Hillman, A., A. Zardkoohi, and L. Bierman. "Corporate Political Strategies and Firm Performance." Strategic Management Journal, January 1999, 67–82.

Kaplan, R.S., and D.P. Norton. The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy Into Action. Boston: The Harvard Business School Press, 1996.

Kotter, J., and L. Schlesinger. "Choosing Strategies for Change." Harvard Business Review, March-April 1979, 106–114.

Kouzes, J.M., and B.Z. Posner. The Leadership Challenge: How to Keep Getting Extraordinary Things Done in Organizations. New York: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1995.

Lewin, K. Field. Theory in Social Sciences. New York: Harper & Row, 1951.

Morgan, B.S., and W.A. Schiemann. "Measuring People and Performance: Closing the Gaps." Quality Progress 1 (1999): 47–53.

Munk, N. "How Levi's Trashed a Great American Brand." Fortune, 12 April 1999, 83–90.

Peters, T., and R. Waterman. In Search of Excellence. New York: Harper & Row 1982.

Plenert, Gerhard, The eManager: Value Chain Management in an eCommerce World. Dublin, Ireland: Blackhall Publishing, 2001.

——. International Operations Management. Copenhagen, Denmark: Copenhagen Business School Press, 2002.

Rucci, A.J., S.P. Kirn, and R.T. Quinn. "The Employee-Customer-Profit Chain at Sears." Harvard Business Review 76, no. 1 (1998): 83–97.

Schiemann, W.A., and J.H. Lingle. Bullseye: Hitting Your Strategic Targets Through Measurement. Boston: The Free Press, 1999.

Thomas, J. "Force Field Analysis: A New Way to Evaluate Your Strategy." Long Range Planning, 1 December 1985, 54–59.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: