CHILD LABOR

Child labor is highly regulated in the United States at both the national and state levels. These laws attempt to protect children, who are statistically much more likely to make mistakes and have accidents than adults, from employment practices that might jeopardize their health or diminish their future opportunities by interfering with their schooling.

Comparable laws exist in many industrial and developing countries, but developing countries—including such major economies as those of China and India—may lack the political motivation or the enforcement power to impose similar protections for young workers. This reality, along with the greater numerical prevalence of abusive child labor practices abroad, has galvanized many U.S. child labor activists and policymakers to pursue international targets for reform. Thus, even while exploitative child labor practices persist in the United States, much of the concern about child labor abuses now focuses on international settings, and particularly on U.S. companies with direct or indirect ties to foreign child labor.

SOCIAL BACKGROUND OF U.S. POLICY

The dominant belief that some types and conditions of work are not appropriate for children originated relatively recently. In agrarian societies the various forms of child labor have tended to be taken for granted, but the spread of industrialization and other social changes in the United States and Europe during the 19th and early 20th centuries gave rise to public outcry against the employment of children. Particularly onerous to children's advocates were factory work, mining, and other dangerous jobs. Their fear for children's safety and freedom from workplace exploitation was coupled with other social changes affecting how children were perceived:

- new ideas about childhood as a cherished and psychologically formative time

- the development of the progressive notion that all young people needed more formal schooling

- the resulting birth of the modern public and compulsory education system

Ironically, these trends best characterized the values of middle-class society, which was much less likely to need to send its children out to work—unlike the urban working class or the rural poor. In other words, child labor debates have always had a socioeconomic class dimension.

These issues converged when reformers argued that children didn't belong in factories and mines, but rather in homes and classrooms. Meanwhile, employers retorted that child labor was voluntary and sometimes necessary when parents, older siblings, and other relatives couldn't earn enough money to support a family. They argued that employment relations were private matters and the government had no right to intervene. At first, most lawmakers and courts agreed, but gradually protective policies emerged.

Although state child labor laws had been on the books as early as 1836, the first national legislation to restrict child labor was the Federal Child Labor Law of 1916. This short-lived act attempted to control child labor by restricting interstate trade in goods produced under certain kinds of child labor. By this time most states already had some form of minimum age for certain types of work. Just two years later the Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional in Hammer v. Dagenhart, claiming that Congress had exceeded its authority. A similar law was struck down in 1924.

As the twenties waned and the Great Depression loomed, more and more children entered the workplace—and more and more children were injured in the workplace, calling the attention of the public to the conditions in the factories. Many states began to pass laws against the employment of young children in dangerous places. Finally, as a part of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 (FLSA), the federal government created a lasting child labor code. The FLSA's child labor provisions set standards and limitations regarding the employment of children under the age of 18 in industry and in agriculture.

CURRENT U.S. LAWS

More than 20 million persons under the age of 18 work for wages in the United States, and the FLSA remains the core federal law governing their employment. The administration and enforcement of these provisions is the responsibility of the Wage and Hour Division of the U.S. Department of Labor. All states have their own child labor laws and compulsory school attendance laws. Where local law differs from the federal, the more stringent of the two must be observed. However, the trend in state laws has been toward relaxing hour limits and registration requirements.

Federally Recognized Hazardous Jobs

| A partial listing based on Department of Labor guidelines |

|

The essence of the law is that work should not interfere with the schooling, health, or well-being of a child. In theory the law applies to migrant children as well as local residents, but critics allege that migrant child laborers enjoy few of the law's protections in practice.

SPECIFIC REOUIREMENTS.

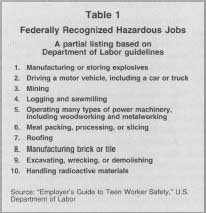

The minimum age for industrial employment is 16 during school hours and 14 after school hours. There are also restrictions on nighttime work, with the exception of certain occupations (including mining) which are considered hazardous. Hazardous occupations, a sampling of which are listed in Table 1, are closed to persons under the age of 18 except under special circumstances. Additional occupations are closed to youths under 16.

Children of 12 and 13, with written parental consent, may work in non-hazardous, non-agricultural occupations. Certain exemptions also exist for children working in a family-owned business, newspaper delivery persons, entertainers, and homeworkers.

In agriculture the requirements are much looser. Minors under 16 years of age may not be employed during school hours unless it is by their parent or guardian and may not operate hazardous machinery as set out in the law. Certain exceptions are made for student-learners and 4-H extension service training programs.

Unless otherwise exempt or a part of a specific training wage plan approved by the U.S. Department of Labor, even child laborers must be paid according to the minimum wage and overtime standards of the FLSA. The minimum wage for employees under age 20 is lower than the general minimum wage, provided that certain criteria are met. Farm workers are not subject to the overtime provisions of the FLSA nor to certain other wage provisions.

Penalties for the violation of the child labor laws include $ 1,000 for violations of each provision and up to $10,000 in fines for each willful violation. They may include prison for repeated willful offenses.

EMPLOYER STRATEGIES.

In some cases an employer can easily determine whether a job is legal for a young worker based on lists published by the Labor Department and other agencies. Other times the regulations are ambiguous, and to avoid legal liability employers must research whether a minor is permitted to work in such a position. Employers can assume that any work involving heavy machinery or vehicles is likely off limits, but there are always a few exceptions. For example, even while most positions that entail driving a car are illegal for minors, some driving is permissible if it meets these and other criteria:

- the driving represents only a small part of the worker's responsibility

- it doesn't involve long distances

- it doesn't require time-sensitive deliveries, such as food

- it doesn't involve transporting more than two passengers at any time

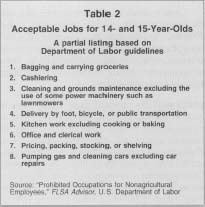

Because of such complex policies and inadequate research on their part, many employers are surprised to learn they've been violating child labor laws. And even when the job is legal for workers under 18, the hours of labor may not be. Table 2 lists some nonagricultural jobs that are legal for workers under age 16.

This means that in order to comply employers must be well-versed in all aspects of the federal and local laws. If there's any doubt about a worker's eligibility, the employer should first contact the local office of the U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division. The department also disseminates employer information over the Internet. The state department of labor should also be consulted to ensure that the offering meets any local criteria that may be more stringent than the federal statute. Employers should keep on file an employment or age certificate for each minor they employ to show that every minor meets age requirements. Every employer, except a parent, should maintain records that show the child's name in full, address, date of birth, evidence of parental permission (if needed), and a detailed record of the hours worked, including the times.

Acceptable Jobs for 14- and 15-Year-Olds

| A partial listing based on Department of Labor guidelines |

|

Many violations occur willfully. Employers or their subordinates may choose to skirt the law out of convenience, cost savings, and so on. The law penalizes this behavior much more harshly than violations stemming from ignorance. Larger companies and repeat offenders are likely to draw the heaviest fines. To reduce the likelihood of either deliberate or careless violation of the law, some companies have instituted policies to educate their employees and reward them for observing the law. In one publicized case, a company paid its young workers a $100 reward any time they reported being asked to do something they weren't old enough to do legally.

GLOBAL CHILD LABOR

According to United Nations figures for 1995, more than 250 million children under age 15 in the developing world work at least part-time, and nearly half of them work full-time. In the worst cases, these children may start as early as age 5 and may work in near-slavery conditions; such practices include the trafficking of children as prostitutes. Tens of millions of children are believed to suffer under such forced labor conditions.

Perhaps the most infamous, albeit not the most common, employers of child labor are textile manufacturers located in countries such as Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, and China. As a result of this notoriety, major apparel and sporting goods companies that do business in the United States have been under pressure to distance themselves from foreign contractors that use child labor and certify that their products are not manufactured by children.

One oft-suggested remedy is for manufacturers to use a distinctive label to market products that they can prove weren't made by children under objectionable circumstances. While a number of companies and nonprofit agencies have supported these proposals, as have some consumers, none of the labeling programs can be said to be particularly effective so far. Another U.S. solution was a 1997 law banning imports of products made from child labor; this, too, produced little result as the U.S. Customs Service, charged with enforcing the ban, appeared reluctant to initiate a trade stoppage without overwhelming and specific evidence that child labor was involved. Critics of both approaches claim that even if these measures were able to curb demand for products made by children, the effects of heightened poverty and greater desperation would likely be worse for those very children than the working conditions in question.

Still, the industrial countries employ their share of underage children in dangerous jobs or in exploitative ways. According to mid-1990s figures from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, a research unit within the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, around 40 percent of U.S. child fatalities in the workplace occurred during a violation of federal child labor regulations.

FURTHER READING:

International Labour Organization. Abolishing Extreme Forms of Child Labour Information Kit. Geneva, May 1998. Available from www.ilo.org .

Sullivan, Christopher. "When Labor Turns Deadly." Los Angeles Times, 4 January 1999.

United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). Child Labour. New York, 1998. Available from www.unicef.org .

U.S. Department of Labor. Bureau of International Labor Affairs. By the Sweat and Toil of Children, vol. 4. Washington, 1997. Available from www.dol.gov .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: