STRATEGIC PAY/NEW PAY

The terms "strategic pay" and "new pay" became established through book titles—Edward Lawler's Strategic Pay in 1990, and J. R. Schuster and Patricia Zingheim's The New Pay in 1992. The concept of strategic pay looks at wages and benefits as one instrument through which an organization can meet its current business goals. Schuster and Zingheim provide the following definition of new pay: "Under new pay, … pay programs respond to specific business and human resource challenges.… New Pay requires the use of all the possible 'communication' to hit the proper performance targets.… base pay, variable pay, indirect pay.… The centerpiece of new pay is variable pay (which) facilitates the employee-organization partnership by linking the fortunes of both parties in a positive manner." New pay programs specifically place portions of all employee pay "at risk." If specified goals are met, all share in the gains; if not, all lose. This simple concept represents a paradigm shift in thinking about pay—from a cost to employers, to an investment by employers.

THE OLD PAY SYSTEM

For many years pay has been handled mechanically. Jobs were evaluated, and points were assigned for "compensable factors" in the job (such as responsibility, skill, mental effort, and working conditions). This approach is called the "point-factor" system. Pay was then related to the points in the job. Bands of jobs were developed in similar point ranges. Naturally, this system resulted in long lists of jobs at many companies (and in the federal government). Apart from the annual raise, one could get more money only by moving up in the point system. This "pay the job" approach had the obvious strengths of objectivity and impersonality. It did not really ask, however, whether anyone actually produced anything, and did not distinguish well between high- and low-performing persons. The concept of "broad banding"—collapsing the long lists of jobs into broader "bands"—was an attempt to address some of the difficulties of extensive job categories and provide a way around the potential lockstep of the point-factor system.

"Pay the person" was an attempt to bring the person more directly into the pay equation. It did so by providing additional money for additional competencies learned on or through the job. "Pay for knowledge" and "pay for skills" systems allowed employees to earn more money if they acquired and demonstrated competence in additional skills. Employers liked this because employees became more broadly capable. Difficulties arose, however, because employees sometimes never got to use their new skills. These approaches lacked a focus on the results as well.

There were some other problems with the old pay system, aside from bureaucratization (pay the job) and disconnection between what people learned and what they could do (pay the person)—misalignment and annuitization. Existing pay practices tend to be unaligned with results. The rhetoric of linkage is used—as in the concept of the "merit raise"—but in many actual cases, there is no merit involved. Somehow, in some way, a raise is determined. Of course alignment with firm goals assumes—wrongly in too many cases—that the firm has goals. Many compensation consultants find that their first job is to help an organization develop the things they wish to pay for. Reward systems were often best described through the title of the classic piece by Steve Kerr, "On the Folly of Rewarding A while Hoping for B. "The new pay emphasis requires that organizations define goals and review performance in a competent manner. Accomplishing these objectives is essential for organizational high performance today, regardless of the pay system. Companies could improve at objective setting and performance appraisal . Thus, initiating a new pay system is one way to usher in needed change. Nevertheless, achieving both of these objectives is difficult, particularly the development of staff skills in the area of performance appraisal. Tales abound of appraisal avoidance, cursory reviews, and unhelpful comments aimed at the person of the employee rather than at the employee's behavior. Without objectives and review, the total compensation idea will not work well.

Annuitization is another problem. Conventional raises" go into the base. Hence, employers are paying for past performance year after year.

In spite of the fact that compensation costs are a large portion of most business operations, neither employees or employers thought of compensation as a total package. While the businessperson may have had a sense of total compensation costs, the employees lacked the idea of total compensation as something for which they worked. And both the business and the employees lacked the idea of total compensation (benefits especially were not seen as "pay" by employees). Rather, it was broken up into components. There was base pay and indirect pay (fringe benefits), as well as a range of bonuses, overtime, perks, and allowances. Yet it was difficult to get all the numbers in one place.

These components were often administered by different parts of the organization. Frequently, base salary was determined under one unit of the organization, using one theory, or a combination of theories. Benefits were often developed and administered under another department with different rationales and philosophies. Bonuses and special pay were often in yet another place. Something new was needed.

THE TOTAL COMPENSATION PACKAGE

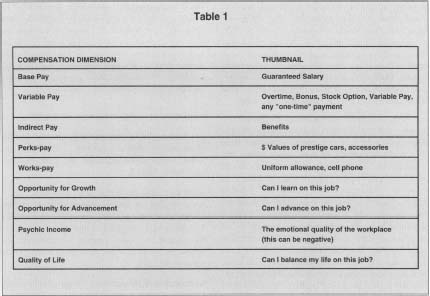

New pay begins with a view that one should think about compensation as a complete, "total" package. Total compensation includes the nine elements outlined in Table 1.

BASE PAY.

Base pay is what many think of as "pay." It can be paid "at market," below, or above market. In the future, base pay will likely become a smaller fraction of total compensation than it is now, and may be targeted at "below market." Individuals and teams can add to their pay through increments in the variable pay area.

VARIABLE PAY.

Variable pay is the portion of pay linked to results. A variety of types of performance goals—individual, team, unit, and total company—can become components of the variable pay amount. While such elements have been present— profit sharing , gain sharing, etc.—they have not usually been linked into a total compensation framework. Employees will be able to add a considerable amount to their "pay," depending upon how they and the firm performs. The structuring of variable pay in this way means that "the paycheck" may vary a good bit more in the future than in the past. Also, variable pay does not go into the base; it is a year-by-year phenomenon.

INDIRECT PAY.

Indirect pay—fringe benefits—has traditionally been viewed as an entitlement program within the company. In New Pay, Schuester and Zingheim stated that the "view of indirect pay is to contain indirect pay costs to free dollars to spend on direct pay, particularly variable pay." Defined-contribution plans are becoming more popular than defined-benefit plans in retirement programs; health care costs are being closely examined. Rather than simply being willing to pick up additional costs, companies are defining the amount of money they wish to convey through indirect pay. This approach frees up dollars which, in previous years, might have gone to benefits automatically. It can now go into variable pay. If they wish, employees can purchase augmented benefits with variable pay dollars, but they can also do other things with the money. Cafeteria benefits is a name for this approach.

PERKS-PAY.

Perks, as a component of pay, are declining. They tend to emphasize status distinctions in

| COMPENSATION DIMENSION | THUMBNAIL |

| Base Pay | Guaranteed Salary |

| Variable Pay | Overtime, Bonus, Stock Option, Variable Pay, any "one-time" payment |

| Indirect Pay | Benefits |

| Perks-pay | $ Values of prestige cars, accessories |

| Works-pay | Uniform allowance, cell phone |

| Opportunity for Growth | Can I learn on this job? |

| Opportunity for Advancement | Can I advance on this job? |

| Psychic Income | The emotional quality of the workplace (this can be negative) |

| Quality of Life | Can I balance my life on this job? |

an era of more flattened, team-oriented firms. There has also been increased tax interest in perks.

WORKS-PAY.

Works-pay is perhaps the most difficult area, as companies try to define what costs of business to employees, such as a uniform or car allowance, should be considered for employee reimbursement. Assembling these components creates learning for employer and employee alike, as each sees the amount of money involved.

OPPORTUNITY FOR GROWTH.

Opportunity for growth addresses the direct and indirect ways employers support personal learning. One way is if the organization itself is a learning organization, and the employee feels that he or she can benefit from mentorship and instruction on the job. More directly, organizations pay for education, sometimes even advanced degrees, such as an MBA or Ph.D.

OPPORTUNITY FOR ADVANCEMENT.

Opportunity for advancement reflects the extent to which the organization has "room at the top." Employees may "sacrifice" higher salary (or "invest" the difference between their highest possible salary and the salary they can get at "opportunimax") in the hope of achieving a high position sooner rather than later.

PSYCHIC INCOME.

Psychic income involves the emotional rewards of the job/career. Priests and nuns, for example, emphasize psychic income, as do Peace Corps volunteers and many in the nonprofit sector. Psychic income can be negative, however, as in the case of a "toxic workplace" that pays well but pays no attention to any other aspects of the employees' lives.

QUALITY OF LIFE.

Some employees seek quality of life, involving a workplace that integrates life in the organization with life outside of the organization. For example, jobs with firms in Los Angeles are likely to require a commute. For some this is fine; for others not. If one wants to ski to work in the winter, only a few firms will be suitable.

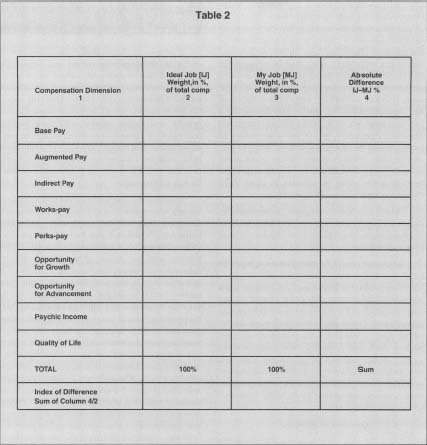

One interesting feature about the total compensation package just discussed is that individuals weigh the kind of compensation they prefer differently. Table 2 allows readers to explore this possibility.

In column 1 is the compensation dimensions. In column 2 individuals can record the importance of each of the dimensions in their ideal job. These weights, of course, may vary over time as individuals are at different points in their career path.

Column 3 asks for the same kind of rating for the individual's current job. Comparisons are achieved by taking the sum of the absolute differences between columns 2 and 3 for each row, and dividing by 2. The result—the index of difference—shows how much space there is between what one would ideally like and what one has at the moment. These numbers can become quite large.

The point of this exercise is not only to create information, but to suggest to employers that the

|

Compensation Dimension

1 |

Ideal Job [IJ] weight, in%, of total comp

2 |

My Job [MJ] Weight, in%, of total comp

3 |

Absolute Difference IJ-MJ%

4 |

| Base Pay | |||

| Augmented Pay | |||

| Indirect Pay | |||

| Works-pay | |||

| Perks-pay | |||

| Opportunity for Growth | |||

| Opportunity for Advancement | |||

| Psychic Income | |||

| Quality of Life | |||

| TOTAL | 100% | 100% | Sum |

| Index of Difference Sum of Column 4/2 |

compensation plans of the future will be more cafeteria-like in nature. That is, individuals will, to a degree anyway, configure their compensation the way many of us now configure our benefits.

IMPLEMENTING A NEW PAY SYSTEM

If an employer or business is considering implementing a new pay system, there are several helpful tips. First, one should get information about the current system and the way it actually works. One needs to look carefully at the current practice; securing information from the full range of employees is likely to be more accepted if it is done by an outside consultant. A company-wide committee of employees might also be helpful.

It is clear that communication with employees is a key element. Overcommunication is usually needed in an organizational effort, and especially when issues of compensation are involved. Communication in a variety of media are helpful (video, print, oral, etc.). Candor in communication, as well as level and mode, is vital. Employees will think that employers are reducing their pay, rather than realigning it. Clarity about the total compensation package, and the ability of employees to affect some of their own compensation through variable pay is essential.

Step-by-step movement is important. Shifting from so-called merit raises to a variable pay raise system is a difficult change. One method is to develop a strategy by which all increments to base and indirect pay are "market related" and anything else is variable, driven by year-to-year performance.

Employers might want to move step by step, however, by allowing some of the variable pay increment to go into base, especially as a transition to a more fully operating variable pay system. The approach below suggests an arrangement of the relation of base increments to variable pay to the employees' percentile position in the range (1/100 indicates the first percentile; 50/100 the 50th, 100/100 the top of the range). For employees at the bottom of the range (1/100), 99 percent of the raise goes in base, and 1 percent to bonus; for employees in the middle of the range, it is half and half; for employees at the top of the range (100/100), all is variable pay. Assume that a particular employee's raise is $2,000. For the person in the tenth percentile, 90 percent of the money, or $1,800, would be an addition to base, while 10 percent, or $200, would be bonus. For the person at the top of the range, it would all be bonus. Over time, the decision points could be adjusted to move more toward a completely variable pay system.

Finally, it is helpful to emphasize the flexibility of the new pay system. The company needs to be as efficient and effective with total compensation as with other expenditures.

Employees need to be motivated through pay. In theory, one does not worry how much staff are paid—what they produce is what counts. In speaking about the new mind-set of organizations, Charles Handy refers to the 1/2 × 2 × 3 formula. It is "shorthand for one executive's goal that in five years there will be half as many people in the core of the company, paid twice as well, and producing three times as much value." As Hal Lancaster wrote, new pay is part of a new social contract between employers and employees that includes "meaningful work, learing opportunities, career management skills, honest communications and no-fault exits."

SEE ALSO : Compensation Administration

[ John E. Tropman ]

FURTHER READING:

Abernathy, William B. The Sin of Wages: Where the Conventional Pay System has Led Us and How to Find a Way Out. Abernathy & Assoc., 1996.

Handy, Charles. "The New Mind-Sets of Organizations." Insights Quarterly, winter 1992, 69-70.

Henderson, Richard L. Compensation Management: Rewarding Performance. 6th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1994.

Kerr, Steve. "On the Folly of Hoping for A while Rewarding B." Academy of Management Executive 9, no. 1 (1995): 7-14.

Lancaster, Hal. "A New Social Contract to Benefit Employer and Employee." Wall Street Journal, 24 November 1994, BI.

Lawler, Edward E., III. Strategic Pay. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 1990.

Lowman, Don. "'New Pay': Compensation for People, Not Jobs." Employment Relations Today 20, no. I (spring 1993): 37-445.

Schuster, J. R., and Patricia Zingheim. The New Pay: Linking Employee and Organizational Performance. New York: Lexington, 1992.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: