SIC 0251

BROILER, FRYER, AND ROASTER CHICKENS

This category includes establishments primarily engaged in the production of chickens for slaughter, including those grown under contract.

NAICS Code(s)

112320 (Broilers and Other Meat-Type Chicken Production)

Industry Snapshot

Although the number of poultry farms decreased by half over the last 50 years, output rose dramatically, from about 1.5 billion birds in 1959 to almost 8.0 billion at the turn of the twenty-first century. By 2002 poultry production had exceeded 38 billion pounds, reflecting a 3.2 percent increase from the previous year. Domestic poultry consumption grew 5.7 percent in 2002 to nearly 76 pounds.

The industry survived the late twentieth century recession reasonably unscathed. In the early 1990s, it had benefited from unprecedented consumer demand for poultry. In 1992 sales of chicken had outstripped those of red meat for the first time. By 2002, chicken accounted for a 41.7 percent share of the meat market.

Chicken was also being marketed more widely, particularly in fast food restaurants. Between 1970 and 1990, about 25,000 outlets introduced chicken in the form of sandwiches or nuggets, and these numbers continued to grow into the twenty-first century. There was also steady growth in the number of specialist fast food chicken chains, such as KFC and Church's Fried Chicken. The broiler, fryer, and roaster industry and the fast food industry have worked closely together to develop products especially for these markets.

Organization and Structure

In the early 2000s, 7 to 10 companies controlled about 50 to 60 percent of the chicken market. These were vertically integrated concerns—companies with control over every stage of poultry growth and production from egg production to broiler slaughter.

By the start of the twenty-first century, independent farmers under contract to large poultry companies grew 89 percent of the chickens, a 10 percent decrease from the mid-1990s. The remainder were farmed directly by the companies themselves. Under the contract system, the company provided the chicks, feed, medication, and transportation to market. The farmer furnished the housing, equipment, labor, and miscellaneous supplies, and agreed to raise the birds until slaughter. Farmers were generally paid according to how much feed was needed for the birds to achieve market weight. The less they needed, the cheaper the chickens were to produce and the more farmers earned.

Background and Development

Broiler production increased from 34 million in 1934 to approximately 6 billion in 1990. Output has increased in all but five of the last 50 years. Better breeding, feeding, and disease control—combined with more sophisticated housing—reduced broiler production time by two weeks between 1980 and 1990. In 1935, it took a farmer 16 weeks to produce a 2.9-pound broiler, with 4.5 pounds of feed needed per live weight. By 1988, a farmer could produce a four pounder in just six weeks, on less than two pounds of feed per live weight. This increase was realized by the use of intensive farming methods; new systems of temperature, feed, and water control; careful breeding; and the use of antibiotics to speed the birds' growth.

Increased national and international demand for chicken and chicken products fueled steady industry growth, about 5 percent per year since the early 1960s. In 1995, chicken producers raised about 7.33 billion birds with sales of over $11.4 billion. Total broiler production continued to increase, surpassing 1995's approximately 34 billion pound level of production. About 50 percent of chickens were sold directly to consumers, another 40 percent were sold to restaurants, and 10 percent went for export or pet food.

Despite a sustained drop in the price of chickens in 1994 and 1995, in 1996 wholesale prices for broilers climbed to about 60 cents per pound, while broiler parts held at roughly $1.92 per pound for boneless breasts and about 96 cents for breasts with ribs on. Retail prices ranged from 98 cents per pound for fresh whole broilers to about $2.05 for bone-in breasts.

In 1996, per capita consumption of chicken stood at 72.9 pounds. The type of chicken consumed changed in the latter part of the twentieth century. Chicken was marketed as "whole," "cut-up and parts," or "further processed." Sales in the latter two categories rose steadily, partly due to the fact that consumers considered them time-saving. The market share of cut-up and parts grew from 15 percent in 1962 to 56 percent in 1990. Sales of further processed chicken also increased, from 2 percent market share in 1962 to 26 percent in 1990, of which boneless chicken comprised 80 percent. Also included in this category were value-added products such as nuggets, which became very popular in the 1990s; chicken strips; patties; and versions of buffalo wings.

However, sales of whole chickens plummeted to about 20 percent of all chicken sales in 1994. This trend continued throughout the 1990s and was predicted to continue into the next century. On the other hand, the popularity of rotisserie chicken, as marketed by restaurants such as Boston Market, somewhat stabilized whole chicken sales.

In 1996, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) revamped its meat inspection system to ensure a high standard of safety. Under the new system, scientific tests and modern technology supplanted the former system, which relied on the inspectors' abilities to perceive contamination themselves. The new method, the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP), required poultry companies and the USDA to participate in an effort to reduce and prevent contamination.

Current Conditions

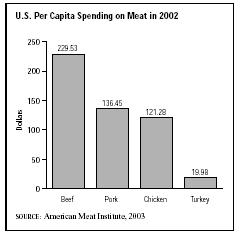

By the start of the twenty-first century, there were 175 poultry-processing plants in the United States. The industry employed approximately 240,000 workers. Poultry production grew 3.2 percent to 38.1 billion pounds in 2002. That year per capita consumption was 75.6 pounds, which amounted to $229.53 in poultry expenditures annually. Boneless chicken breasts continued to be the most popular cut.

Controlling the spread of disease and ensuring worker safety will most likely continue to be two of the major challenges facing the poultry industry throughout the twenty-first century. In 2002, Pilgrim's Pride instituted the largest meat recall in U.S. corporate history when it removed 27 million pounds of poultry from shelves due to suspected contamination with listeria.

Another example has to do with the impact of chicken processing on the environment. Chicken feed contains large amounts of the strengthening nutrient phosphorus, which is difficult for chickens to digest. Therefore, the chickens' waste material, much of which is used as manure, also contains high levels of phosphorus. If manure runs off into ponds and streams, human water supplies can be endangered. Industry researchers and scientists from the University of Delaware have worked to develop a corn hybrid with a more easily digestible phosphorus. However, processors still face public perception of the negative effects of genetically altered foodstuffs, and it may be some years before such products see widespread use.

In the early 2000s, consumer concern regarding antibiotic use at poultry plants began to rival concerns regarding disease. As a result, industry leaders Tyson Foods, Perdue Farms, and Foster Farms began to remove antibiotics from feed for healthy chickens.

Worker safety was also a concern, since increased product demand and faster machinery had significantly increased the USDA-maximum production line speed from 70 birds per minute in 1979 to up to 180 birds per minute by the early 2000s. The rate of worker injuries had also increased so that cumulative-trauma disorders, such as carpal tunnel syndrome and tendonitis, were 16 times the national average among poultry workers. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health determined that 49 percent of the workers in one plant's deboning line sustained injuries to their upper bodies. Additionally, the U.S. Department of Labor estimates that one in every six workers will suffer some sort of on the-job injury, compared to a rate of one in twelve for the manufacturing industry in general.

Industry Leaders

The industry was dominated by Tyson Foods, Inc. in the early 2000s producing over 25 million head of chicken. In 2003, Pilgrim's Pride Corp. bought the chicken processing assets of ConAgra Inc., becoming the second largest poultry processor in the United States. Other industry leaders included Gold Kist and Perdue Farms.

Tyson Foods, Inc., based in Springdale, Arkansas, was the world's largest producer, processor, and marketer of poultry-based foodstuffs. The bulk of its business was concerned with value-enhanced poultry products, such as chicken patties, precooked and prepackaged chicken, and Rock Cornish hens. Tyson controlled all aspects of its poultry production, from genetic research and breeding, to hatching, rearing, and feed milling. It was also concerned with veterinary and technical services, transportation, and delivery. With 120,000 employees, Tyson posted sales of $24.5 billion in 2003.

John Tyson, the grandfather of the current chairman, entered the poultry business in the 1930s, although it was not until 1947 that the company was incorporated under the Tyson name. After starting out as a dealer in chicken, John Tyson began raising them. During the 1950s, the company significantly expanded, and in 1958 it opened its first processing plant in Springdale, Arkansas. In 1960, Don Tyson became manager. Three years later, he renamed the company Tyson's Foods, Inc. and introduced Tyson Country Fresh Chicken, packaged birds that have become the company's mainstay. In 1971, the name was changed yet again to Tyson Foods, Inc.

Although the company has grown steadily over the years, a veritable explosion in its trade occurred in the 1980s, as health conscious consumers switched from red meat to chicken. By 1985, it had achieved $1 billion in annual sales. Between 1984 and 1989, Tyson's profits more than quadrupled, while its revenues tripled. Tyson Foods had consolidated its dominance of the market by purchasing key poultry operations, including Prospect Farms, Consolidated Food's (now Sara Lee) Ocoma Foods Division, Heritage Valley, Lane Processing, and the Tasty Bird division of Valmac. In 1989, it beat out rival ConAgra, Inc. for control of Holly Farms, the nation's leading brand name broiler producer. Tyson was also involved in the Mexican food business, produced byproducts for pet food, and acquired a stake in a fishery.

Headquartered in Springdale, Arkansas, the chicken capital of the nation, Tyson Foods also had processing plants in 13 states. As of 2004, it was run by chairman and CEO John H. Tyson. In addition to being number one in the U.S. market, Tyson exported to Canada, Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, the Commonwealth of Independent States, the Middle East, the Far East, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Japan had also become an important customer of Tyson chicken: Tyson supplied Japan with over 50 percent of all its U.S. chicken imports.

Tyson Foods' chief competitor was Pilgrim's Pride Corp., a diversified food company that became number two in the U.S. poultry business in 2003 when it acquired the chicken processing arm of ConAgra, Inc. The company as a whole earned $2.6 billion in fiscal 2003 for all of its divisions and employed a total of 24,800 people. Based in Pittsburg, Texas, Pilgrim's Pride markets its products in Asia and Europe, as well as in the United States. It is headed by chairman Lonnie Pilgrim.

ConAgra had been involved in the broiler industry since 1982 when it bought Country Pride, a leading producer of broilers. It continued to market chickens under this label and also under its Country Skillet and Frozen Banquet brands. ConAgra came into existence in 1919 as the Nebraska Consolidated Mills Company. Its founder, Alva Kinney, concentrated on the grain milling business, and it was not until the late 1940s that the company entered the prepared foods industry. The company continued to diversify through the 1960s, when it first gained an interest in the chicken market, developing poultry growing and processing sites in Georgia, Louisiana, and Alabama. In 1965, it expanded into the European market, eventually forming a partnership with Bioter Biona, SA, a Spanish breeder of chickens, other livestock, and animal feed. In 1971, the company changed its name to ConAgra, meaning "in partnership with the land." It was first listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 1973.

During the early 1970s, the company languished as many of its acquisitions failed to thrive. In 1975, former Pillsbury executive Charles Harper was brought in as president to turn ConAgra around. He purchased Banquet Foods Corporation in 1980 as a way to increase ConAgra's share of the chicken market. In 1982, ConAgra moved into first place in the chicken industry when it formed Country Poultry, Inc. By the following year, the division was the nation's biggest poultry producer, with more than a billion pounds of brand-name broilers. In 1987, it tightened its grip on the broiler industry when it bought Longmont Foods, another poultry producer. It was eventually pushed into the number two spot by Tyson Foods. Competition between the two companies intensified in 1999 when Tyson filed suit against ConAgra, charging ConAgra with luring away four top ranking Tyson employees and stealing company secrets. Tyson eventually won the legal skirmish.

Atlanta-based Gold Kist Poultry Group, a farmers' cooperative formed in 1933, reported sales of $1.85 billion in 2003 and employed 17,000 people. Perdue Chickens, a privately-run company headed by James Perdue and based in Salisbury, Maryland, reported sales of $2.7 billion in 2003 and employed 20,000 people. Leading chicken-producing states included Arkansas, Georgia, Alabama, North Carolina, and Mississippi.

Workforce

U.S. chicken processors employ a total of about 240,000 workers. Approximately 73 percent of chicken farms employed fewer than four workers in the early 2000s, and over 9 percent employed between five and nine workers. About 4.5 percent of operations employed over 100 people, while 2 percent employed between 10 and 14, and 3 percent, between 20 and 49. Approximately 1 percent employed between 15 and 19 and 1 percent between 50 and 99 workers.

Although most poultry farmers worked as independent contractors for the large poultry companies, their relationship was usually one of dependence. Fewer poultry producers meant that farmers often had no choice but to take what they could get. Although they may have depended on a company for their livelihood, they did not enjoy the benefits of employment, such as workers' compensation, health insurance, or paid vacation time. In order to be eligible for a contract, growers had to invest heavily in plants and equipment, thus tying themselves up with debt for long periods of time. Their contracts with poultry companies did not last the length of their mortgages, but were automatically renewable unless either party wished to cancel. In practice, this meant that farmers were guaranteed no more than the next flock of chickens.

Although there was some talk of setting up a growers' organization to lobby for legislative change in the industry, growers were fearful of being boycotted or blacklisted by the producers if they tried to organize. The poultry industry's political clout was legendary. Its political action committee contributed hundreds of thousands of dollars to politicians, particularly those from the South. John Tyson, head of the largest poultry company, was a personal friend of former-president Bill Clinton and contributed generously to his election campaign. The poultry companies defended the contract system by pointing out that they provided employment, and that they offered farmers a steady income.

Some steps to protect the growers have been taken, although growers said they did not go far enough. They wanted to see laws that would require poultry companies to: pay them within a specified time; provide for mediation in the case of disputes; allow growers to recoup their investment if the contractor backed out of the deal; adjust prices for growers whose income was affected by weight; and prevent unfair trade practices.

America and the World

Most of the market leaders had a stake in the poultry market abroad. For example, Tyson Foods, Inc. had important markets in western Europe, the Caribbean, Mexico, and the Pacific Rim. The latter alone accounted for almost 50 percent of all exports in this category. Demand for U.S. chicken had also increased in Russia and former Soviet Union countries. According to the USDA, exports reached a record 5.5 billion pounds in 2001, accounting for 18 percent of U.S. broiler production. Russia and China, including Hong Kong, accounted for nearly 60 percent of all U.S. exports. South Africa, Mexico, Canada, and Japan were also significant importers of U.S. poultry.

The future of poultry exports faced uncertainty in the early 2000s, due to various quota and bans put in place by other countries. For example, Russia established a quota of 553,500 metric tons for U.S. chicken imports on May 1, 2003. Due to concerns over the use of antibiotics during production, the Ukraine banned U.S. chicken imports on January 1, 2002. At various times throughout the early 2000s, Japan banned U.S. poultry imports due to the presence of Avian Influenza discovered in U.S. chickens. Exports in 2002 declined 13.6 percent, although USDA forecasts called for this number to rebound as the U.S. poultry producers began to resolve trade disputes with other countries.

Further Reading

American Meat Institute. Overview of U.S. Meat and Poultry Production and Consumption. Arlington, VA: March 2003. Available from http://www.meatami.com/content/presscenter/factsheets_Infokits/FactSheetMeatProductionandConsumption.pdf .

U.S. Department of Agriculture. Livestock, Dairy, and Poultry Outlook. Washington, DC: 27 January 2004. Available from http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/reports/erssor/livestock/ldpmbb/2004/ldpm116t.pdf .

U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Poultry and Eggs: Trade. Washington, DC: 14 November 2004. Available from http://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/Poultry/trade.htm .

"U.S. Meat Firm in Massive Recall Over Listeria." European Intelligence Wire. 15 October 2002.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: