SIC 0174

CITRUS FRUITS

This industry consists of establishments primarily engaged in the production of citrus fruits.

NAICS Code(s)

111310 (Orange Groves)

111320 (Citrus (except Orange) Groves)

Industry Snapshot

Citrus fruits include oranges, tangelos, temples, tangerines, lemons, limes, and grapefruits. Oranges make up about 65 percent of total worldwide citrus production; tangelos, temples, and tangerines make up 15 percent; lemons and limes 10 percent; and grapefruits, 10 percent. Oranges and grapefruit account for approximately 90 percent of U.S. citrus production.

With more than 20,000 U.S. producers of all sizes, no one grower is dominant in the production phase. The industry governs its own marketing orders. Growers heed marketing factors as they specify grade and standard of crop leaving the region. They control the amount of product leaving the region during marketing season, and designate periods when no new product can be shipped. Growers also provide market support such as research and price information, and provide market development programs. Throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s, the number of citrus fruit acres planted has steadily declined. Acres planted in 2002 totaled 1.05 million, compared to 1.15 million in 1997.

Organization and Structure

Florida, California, Texas, and Arizona, all subtropical regions, produce the bulk of citrus fruits in the United States. Tropical cultivation is not as productive since seasonal changes are necessary for proper fruit growth. Citrus trees can withstand short periods of light frost, but hard frosts of long duration can be devastating.

The modern citrus industry depends on regular and frequent irrigation, fungicides, herbicides, pesticides, and other fertilizers. Harvesting is still often accomplished through manual means, although mechanical techniques are increasingly being used.

In the fresh fruit market, there is a great deal of competition, especially considering that, since around 1970, the per capita consumption of fresh oranges has declined, and since 1976, the consumption of fresh grapefruit has also decreased. With some fluctuations in between, per capita consumption of oranges has dropped from 16.2 pounds in 1970 to 12.1 pounds in 2002, while grapefruit consumption tapered off from 8.2 pounds in 1970 to 4.8 pounds in 2002. Of the total orange harvest in 2002, only 14 percent was consumed as fresh fruit, while 40 percent of grapefruits were consumed fresh. In the United States, almost all fresh citrus was garnered from domestic sources.

Processed fruit takes two forms: ready-to-serve juice (also known as single-strength equivalent, or SSE) and concentrate. Both forms have become very popular among consumers, mostly for their convenience. The variety of canned, frozen, and ready-to-serve juices in supermarkets is clear evidence of how the public responds to the processed product.

Citrus growers in the United States generally operate under one of three production philosophies. The first of these is to physically hand the fruit over to a packing-house, processor, or middleman. A second option involves contracting with the packinghouse, processor, or middleman before the fruit is ready for harvest. In both cases, the seller and buyer agree to a satisfactory price before the fruit goes to market. The third option is an arrangement wherein the grower places his fruit along with a number of individual growers into a "pool" for sale on the open market. Profit is then determined by the selling price of the pooled fruit.

Citrus processing is a lucrative business. In addition to the primary products of frozen concentrate, chilled juice, and canned juice, processing also yields a number of by-products such as food additives, pectin, marmalades, cattle feeds (from the peel), cosmetics, essential oils, chemicals, and medicines. The processor can sell all these products to the appropriate industry for a profit.

Background and Development

Until the 1950s, citrus fruits were cultivated and traded on a local basis almost exclusively. Speed and care in shipping the perishable fruits were of great concern. However, the development of citrus concentrate in the late 1940s had a lasting impact on the citrus industry worldwide. Concentrating the fruit permitted the storage, transportation, and transformation of product far from the groves. In contrast to fresh fruit consumption, processed citrus consumption has remained fairly stable since 1972. According to the Florida Department of Citrus, Economic and Marketing Research Department, per capita orange consumption in processed form (frozen concentrated juice, chilled juice, and canned single-strength) has fluctuated little since the early 1970s. Since the 1970-71 growing season, retail prices have risen steadily, in large part because of the healthy market for frozen concentrated orange juice.

By the 1995-96 growing year, Florida processed about 85 percent of the oranges and grapefruits grown in the United States, including 64 percent of its own orange production and 57 percent of its grapefruit crop. This process effort yielded 94 percent of the nation's frozen concentrated orange and canned orange juice, as well as 76 percent of canned grapefruit juice. In 1996, the USDA projected that U.S. orange juice production would rise to its record level of 1.3 billion SSE gallons. However, not all of the fruit processed was domestically grown. Nearly half of all processed juices available in America come

from imported juice concentrate. Under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), for example, the United States must import 44.1 million (SSE) gallons.

In recent years, cooperatives have been created in all four citrus producing states; in Florida they account for 22 percent of that state's processing volume. Conglomerate integration—firms that are subsidiaries of national food conglomerates—is also a significant presence in the industry, processing 35 to 45 percent of all the citrus that Florida processes.

Current Conditions

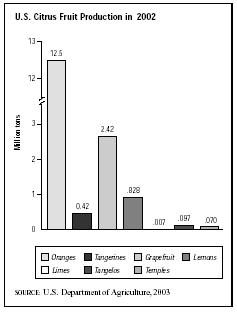

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the citrus industry, which is based primarily in Arizona, California, Florida, and Texas, produced 16.3 million tons of citrus fruit during the 2002 growing season, as opposed to the record-high 17.8 million tons produced in 1996. The drop in production is attributed to fewer acres planted, the result of reduced demand. Oranges constitute the country's largest fruit crop with nearly 12.5 million tons produced in 2002.

Total orange-bearing acreage in the United States reached its peak during the early 1970s. After receding for a period following the 1979-80 season, the total acreage devoted to citrus production began to rise in 1996-97, but has fallen off slightly since then. According to the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), a division of the USDA, in the 2002 growing season, approximately 1.05 million acres were devoted to citrus production, compared to 1.15 million acres in 1997. Among the four major producing states, orange-bearing acreage was as follows: Florida had 70 percent; California had 28 percent; and Texas and Arizona together claimed approximately 5 percent of total orange-bearing acreage. Florida, as the major supplier of grapefruit, held around two-thirds of the acreage of the crop. Texas and California together accounted for nearly 23 percent of grapefruit acreage.

After peaking at 13.6 million tons in 1998, orange production in the United States plunged to 9.8 million tons before rebounding to 12.2 million tons in 2001. Production climbed further to 12.5 million tons in 2002. Grapefruit production has seen a more gradual, consistent decline with production falling from 2.6 million pounds in 1998 to 2.42 million pounds in 2002. Tangerine production climbed from 373,000 tons in 2001 to 420,000 tons in 2002, while lemon production dropped from 996,000 tons to 828,000 tons and lime production fell from 11,000 tons to 7,000 tons over the same time period.

The citrus industry has also been enmeshed in controversy in recent years. Citrus growers have long enjoyed the benefits of Depression-era laws that established quotas governing citrus sales. Deepening concern about reputed abuse of the quotas by Sunkist and a number of its leading cooperative members prompted the government to eliminate 1993 marketing orders for navel oranges. With the quotas effectively blunted, wholesale prices plunged. Sunkist has been particularly wounded, both by the allegations that the firm used these quotas to increase retail prices and the financial difficulties brought on by the removal of the quotas. Despite their ongoing tribulations, however, Sunkist, with sales of $964 million in 2002, remains the world citrus industry's wholesale giant.

Industry Leaders

Leading establishments in the citrus fruit production industry are located in Florida and California. Companies such as Duda and Sons Inc., Lykes Bros., Inc., Orange-Co Inc., and Ben Hill Griffin Inc. are among the leaders in Florida, while leading companies in California include Royal Citrus Co., Limoneira Co., ET Wall Co., and Pandol Brothers.

The best known distributor of citrus fruits in the United States is Sunkist Growers, Inc. For the past 104 years it has been the dominant force for citrus growers in California and Arizona, and is a formidable presence in Florida as well. It operates a cooperative of some 6,000 members and accounts for 65 percent of the growers in the states of California and Arizona.

America and the World

The largest citrus producing countries, accounting for more than 70 percent of the world's supply, include the United States, Brazil, Japan, Spain, Italy, Egypt, South Africa, and Morocco, with Brazil leading the world in citrus production. With oranges and grapefruit accounting for approximately 90 percent of all U.S. citrus production, Florida has become a world player; it, along with Brazil, produces most of the world's concentrate.

While the U.S. fresh and processed orange industry is domestically oriented, imports are expected to grow largely due to two factors: the heightened demand for chilled orange juice and improved port facilities. At the same time, these improved facilities allow for more exports, a facet of the industry that growers are trying to enhance. The United States exports orange concentrate to both Canada and Mexico. These exports account for less than 10 percent of the total American domestic supply. Demographically and in price structure, the Canadian market differs little from the United States, and before 1986, Canada was the major purchaser of U.S. exports of orange concentrate. Since January 1994 when the NAFTA guidelines were implemented, frozen concentrated orange juice (FCOJ) exported to Mexico has quintupled, whereas the importing of SSE orange juice has gradually decreased about 20 percent of what it was in 1990. Also on account of NAFTA, which gives products from the United States preferential treatment, all citrus juices made from only one fruit must come only from NAFTA-grown fruit.

In contrast, the European market is very different demographically from the United States. European imports from other suppliers, such as Spain, are priced substantially lower than the American product. To alleviate the disparity, the industry has proposed a two-price system, in order to maintain the price of concentrate sold domestically (already higher relative to the rest of the world), and export the concentrate at a lower price to successfully compete.

To further interest in concentrate produced in the United States, which has been steadily declining in popularity for ten to fifteen years, growers have advanced programs in quality control, packaging innovations, and cross-merchandising, where, for example, FCOJ is paired and successfully marketed with another breakfast food such as waffles. The Duty Drawback Program is another program designed to encourage processors to develop foreign markets. It states that if, within a three-year period, a processor or importer exports a specific quantity of concentrate, duties paid on imports of "like concentrate" will be refunded, or "drawn back."

The export of fresh grapefruit is also of concern to U.S. growers, especially when dealing with Japan. Trade restrictions, import quotas, embargoes, and tariffs have resulted in substantially higher prices for American grapefruit in the Japanese market, yet, even with home-grown grapefruit available, the demand in Japan for fresh grapefruit allows U.S. growers to capitalize on the market.

Citrus exports to Korea grew 41 percent in the 2001 growing season due to lower duty fees there. As part of the Uruguay Round Agreement, Korea had established a quota of 15,000 tons for citrus fruit in 1995. As stipulated by the agreement, this quota increased by 5,000 tons in both 1996 and 1997. Thereafter, it increased by 12.5 percent annually through 2004. U.S. exports to Korea that meet the quota requirements are charged significantly less duty that non-quota imports.

Further Reading

U.S. Department of Agriculture. "Fruit and Tree Nuts: Background." Washington, DC: Economic Research Service, 10 September 2002. Available from http://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/FruitandTreeNuts/background.htm .

U.S. Department of Agriculture. "Fruit and Tree Nuts Outlook." Washington, DC: Economic Research Service, 28 January 2004. Available from http://www.ers.usda.gov .

U.S. Department of Agriculture. "Washington Agri-Facts." Washington, DC: Washington Agricultural Statistics Service, 28 January 2004. Available from http://www.nass.usda.gov/wa/agri2jan.pdf .

"U.S. Orange Exports to Korea Continue to Be Bright Spot." AgExporter, October 2001.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: