SIC 0762

FARM MANAGEMENT SERVICES

This category describes establishments primarily engaged in providing farm management and maintenance services for farms, citrus groves, orchards, and vineyards. Such activities may include supplying contract labor for agricultural production and harvesting, inspecting crops and fields to estimate yield, determining crop transportation and storage requirements, and hiring and assigning workers to tasks involved in the harvesting and cultivating of crops; but establishments primarily engaged in performing such services without farm management services are classified in the appropriate specific industry within Industry Group 072. Workers with similar functions include agricultural engineers, animal breeders, animal scientists, county agricultural agents, dairy scientists, extension service specialists, feed and farm management advisors, horticulturists, plant breeders, and poultry scientists.

NAICS Code(s)

115116 (Farm Management Services)

The overall trends in the farming industry portend good news for farm managers. With the increasing consolidation and centralization of farming activities and a more market-oriented approach to the business, farmers are likely to find farm managers ever-more attractive. In the early 2000s, roughly 60 percent of all U.S. farmland was operated by someone other than its owner. According to the Occupational Outlook Handbook, farmers, ranchers, and agricultural managers accounted for 1.4 million jobs in 2002. The industry is served by the American Society of Farm Managers and Rural Appraisers.

Professional farm managers have a variety of duties and responsibilities. For instance, the owner of a large

livestock farm may employ a farm manager to supervise a single activity such as feeding the animals. At the other end of the spectrum, a farm manager working for an absentee farm owner may have the responsibility for all functions, from planning the crop to participating in the planting and harvesting activities. Professional farm managers must be able to establish output goals, determine financial constraints, and monitor production and marketing. Farm management firms often handle the financial business of client farms, including the buying and selling of products and even the farmland itself. In addition, a number of firms provide consulting services to farmers and farming companies.

Many types of farming are seasonal. Although farm managers on crop farms tend to work all day during the planting and harvesting seasons, they often work on the farm less than 7 months a year. They spend the rest of the year planning the next season's crops, marketing their output, and repairing machinery. Farm managers can achieve Accredited Farm Manager (AFM) certification by the American Society of Farm Managers and Rural Appraisers, after sufficient academic training and job experience.

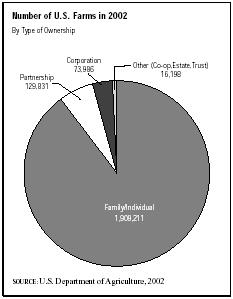

As more people without agricultural backgrounds come to regard farmland as a good investment rather than a vocation, and as family farms give way to corporate farms, farm managers are growing in number and influence. Between 1997 and 2002, the number of family farms declined from 1.92 million to 1.90 million. However, the number of corporate farms also declined, from 185,607 to 129,831, reflecting an industry trend toward consolidation. As a result, the employment outlook for this industry remained less than favorable in the early 2000s. The average wage for agricultural managers in 2002 was $43,740.

Among the leading farm management services firms are Orange-co, Inc. of Bartow Florida, with 500 employees; Farmers National Company, with 130 employees and 3,600 clients throughout the Midwest; Indian River Exchange Packers of Vero Beach, Florida, employing 350 workers; and Sun-Ag, Inc. of Fellsmere, Florida, with a payroll of 550 employees.

The early 2000s was a difficult time for many farmers. The industry's vigorous competition, exacerbated by the lowest agricultural commodity prices in decades heightened the demand for shrewd management practices. Proper crop, soil, and feed management systems could make or break a farming enterprise in this environment. Of growing importance was the handling of efficiency measures to cut down on costs and pollution, especially in the socially and economically sensitive areas of water and fertilizer management. Farms were falling under heavy scrutiny by environmentalists, consumers, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture to diminish waste production and eliminate pollution.

One avenue by which farm managers were beginning to recognize financial and efficiency gains was in the trading of emissions between agricultural and industrial operations. Farmers were increasingly called on to overhaul animal-waste-management and fertilizer-application systems and in general gear agricultural processes toward the limiting of greenhouse-gas emissions in accordance with the U.S. standards adopted by President Clinton at the Kyoto Conference in 1997. While the practice of pollution trading has existed for years, it traditionally involved the transfer of pollution credits from one party to another. Greenhouse-gas emissions, on the other hand, involve the actual purchase of the reductions in agriculturally based emissions by industrial firms who can then allocate the emissions allotment in accordance with their industry's regulations. It thus creates a financial incentive for farm managers to streamline farming operations for greater efficiency.

Farm managers need to keep abreast of continuing advances in farming technologies. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, more and more farm managers were using precision agriculture or site-specific farming methods to customize the placement of seed, fertilizer, and chemicals to get more bushels of grain from their land, reduce waste, and prevent pollution of streams. For instance, Ag Technology Inc. estimates that 8,000 yield monitors are in use across the United States. Yield monitors attached to combines measure the harvest as the combine gathers it. Over one-third of the farm managers using yield monitors also use a global positioning satellite, paired with a receiver that correlates the satellite reading with a fixed point on the ground. Some farm managers are supplementing these technology tools with Geographic Information System, a mapping software.

The passage of the Federal Agriculture Improvement and Reform (FAIR) Act, popularly called Freedom to Farm, was a significant event in this industry in 1996. This new legislation marked the beginning of the gradual departure of government from farming and planting decisions. Once this law was passed, farms began moving toward a market-oriented approach to operations. While this law was always a thorn in the side of small farmers and populist farming organizations for reducing government programs to aid farmers, generally to the advantage of large agribusiness firms, the Freedom to Farm Act has met with increasing calls for reexamination from the latter groups as the slumping commodities prices began to eat into profit margins. It was widely expected that the Freedom to Farm Act would be overhauled before its provisions were to expire in 2002. This prediction came to fruition in May of 2002 when President George W. Bush signed into law the 2002 Farm Act, which increased government subsidies to farmers through 2008.

Further Reading

Ayer, Harry. "The U.S. Farm Bill: Help or Harm for CAP and WTO Reform." Agra Europe, 24 May 2002.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. U.S. Department of Labor. Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2004-05 Edition. Washington, DC:2004.

Food and Agriculture Policy Research Institute. "Implications of the 2002 U.S. Farm Act for World Agriculture." 24 April 2003. Available from http://www.fapri.missouri.edu .

U.S. Department of Agriculture. National Agriculture Statistics Service. 2002 Census of Agriculture. Washington, DC: 2002. Available from http://www.nass.usda.gov/census/census02/preliminary/cenpre02.txt .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: