SIC 0214

SHEEP AND GOATS

This classification covers establishments primarily engaged in the production of sheep, lambs, goats, goats' milk, wool, and mohair, including the operation of lamb feedlots, on their own account or on a contract or fee basis.

NAICS Code(s)

112410 (Sheep Farming)

112420 (Goat Farming)

In 2002 there were 64,170 sheep operators in the United States, compared to 68,810 in 1998. The number of operations has continued to drop each year since 1992 when the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported about 100,000 sheep operations. Although sheep and goats are produced in every state, western states produce 80 percent of the total U.S. flock. Sheep and goats are among the most versatile animals in the world. They can live in many climates from the desert Southwest to the colder climates of Wyoming, and they can efficiently turn barely edible browse into food and fiber. Many farmers use sheep to clean up crop residues. In the West, sheep are often run on alfalfa fields under temporary fence. Goats, however, are even more hearty than sheep, and, therefore, can make do on land that even sheep cannot.

Along with the decline of operations is the decline in gross sheep and lamb production. According to USDA-NASS Agricultural Statistics, in 2003 the total number of sheep and lambs was 7.8 million, down 4 percent from 2002. Breeding sheep numbered 4.6 million in 2003, while market sheep and lambs numbered 3.2 million, both reflecting a 4 percent decline from 2002.

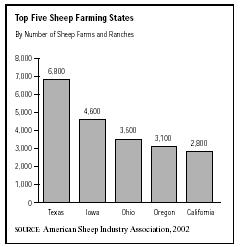

Sheep. In eastern states the farm flocks are generally small, while in the West the flocks are much larger, often

numbering in the thousands. The top five sheep-producing states as of 2002 were Texas, California, Wyoming, South Dakota, and Colorado. Texas alone accounted for 1.05 million of the 6.4 million sheep raised by farmers and ranchers in 2003. California boasted a sheep population of 790,000; Wyoming, 460,000; South Dakota, 380,000; and Colorado, 370,000.

Sheep production in the United States is unique among all sheep-producing countries, because the U.S. market emphasis is on meat, rather than wool production. Three-fourths of the American sheep producer's income is derived from the sale of meat, whereas, in the rest of the world, wool is the primary commodity. Sheep that are processed before the joints in their legs ossify produce meat referred to as "lamb," while older sheep produce mutton. There is a very distinct difference between the two types of meat, and lamb is priced significantly higher.

The female sheep is called a ewe and she may give birth to one or more lambs. The national average is 1.1 lambs per ewe per year. Sheep producers are weaning 20 percent more lambs per ewe in this country than 10 years ago. The lambs are raised in the spring and are processed for meat when they reach approximately 125 pounds at 5 to 6 months old. Most lambs go straight to processing right off grass, but some lighter lambs may spend the final finishing stage in a feedlot eating a high-concentrate grain ration. Many sheep flocks are still herded by Basque shepherds and their well-trained dogs.

Consumer demand for the taste of fresh American lamb is growing, especially at restaurants, where usage is up dramatically. Consumers are eating 16 percent more lamb than ever before and retailers are allocating 38 percent more shelf space to selling American lamb. Lamb prices commanded by producers, however, have fallen in recent years, while the retail price of lamb has risen.

The sheep industry has experienced some wild price swings. In just one year the price of lamb per head fell from $100 to $45. Prices rose in 1996 to $86.50 per head, yet they have fluctuated greatly in the past decade. Wool prices grew 25 percent in 2003 to an average of $0.72 per pound, or a total value of $27.4 million, from $21.9 million in 2002.

Historically, American lamb producers have blamed the lamb packing industry, which has become concentrated into a few hands, and imports from Australia and New Zealand for their losses. To differentiate their fresh product from frozen imported products, the American Lamb Council launched a program in 1990 to label and market selected fresh American lamb that is leaner than the imported product. The program has been successful and that product now accounts for 22 percent of the American lambs being marketed.

Beginning in the late 1990s, increased imports of lamb meat from Australia and New Zealand began to endanger the survival of U.S. sheep producers, according to the American Sheep Industry Association. In September 1998, the American Sheep Industry Association and industry supporters filed a Section 201 trade action petition with the U.S. International Trade Commission. The Trade Commission investigated the effects of increased lamb imports on the U.S. sheep industry and reported recommendations to the White House. On July 7, 1999, President Clinton imposed a three-year tariff-rate quota program and $100 million in assistance to the sheep industry. The program began in July 1999, and imposed a tariff on all lamb imported from Australia and New Zealand through July 2002.

Although the United States is not a major player in the world wool market, U.S. wool is known for its bright color and strength. Domestic wool production fell to 38.1 million pounds in 2003, compared to 41.2 million pounds in 2002; 53.8 million pounds in 1997; and 89.2 million pounds in 1989. The number of sheep and lambs shorn declined 8 percent to 5.06 million head in 2003. Wool exports fell from $108.5 million in 2001 to $91.6 million in 2002. Because of fluctuation in payments, U.S. farmers have typically shied away from wool production. Also, world output of wool is 6 percent higher than demand, and it could take 10 years just to eliminate the wool stockpiled in Australian warehouses. However, the sheep industry remains a vital contributor to the U.S. economy. Sheep contribute $7 billion to the gross national product when domestic lamb and wool production is sold at the retail level. The production of lamb and wool in this country accounts for 350,000 jobs.

Sheep killed by animal predators is a serious issue for livestock operators. At the turn of the twenty-first century, predators accounted for approximately 36 percent of sheep and lamb losses, resulting in lost income of an estimated $35 million, according to the American Sheep Industry Association. Coyotes are the major predator of sheep and lambs.

Goats. The American goat industry is made up of milk goats that are run in small farm flocks and backyard operations as well as large mohair operations primarily in the dry and arid southwestern states. Mohair, like wool, creates a versatile fabric for warm and cold weather and can be found in apparel and furniture. Goat meat has increased in popularity in the United States, as well.

Texas is the leading mohair producing state, while New Mexico and Arizona produce nearly all of the rest of the country's mohair. The three-state total for goats clipped in 2002 was 248,000 head, down considerably from 936,000 head in 1997, according to USDA-NASS Reports . In 2002, each goat averaged a clip of 7.6 pounds, up slightly from 7.3 pounds in 1997. The goat producer received approximately $2.48 a pound for the mohair in 1998, up from $2.25 per pound in 1997. The USDA estimated that the value of the 2002 yield was $3.1 million, reflecting a decline of 9 percent from 2001.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, during World War II and the Korean conflict, the United States imported half the wool required for military uniforms and blankets. The National Wool Act of 1954 was enacted to reduce dependency on foreign wool imports and increase domestic production by providing a subsidy for wool and mohair producers in the United States. The subsidy provided direct payment to farmers based on their production: the more wool they produced the more federal funding they received. A portion of the import tax levied on wool provided the money for the subsidy program. In 1955 the amount of wool sheared was 283 million pounds compared to 89 million pounds in 1988. The price of mohair dropped from $5.10 per pound in 1979 to just $0.95 per pound in 1990. In 1993, Congress voted to eliminate the subsidy at the end of the 1995 fiscal year, saying the program had failed to increase domestic wool production, disproportionately benefited the few largest producers, and wool was no longer a strategic material. The Federal Agriculture Improvement and Reform Act of 1996 upheld the earlier elimination of wool and mohair subsidies, in an effort for the government to reduce spending. However, the 1999 Omnibus Appropriations bill and the 2000 Agriculture Appropriations bill made interest free loans available to mohair producers once again. In the early 2000s, the U.S. government put into place Wool and Mohair Assistance Loans and Loan Deficiency Payments covering the 2002-07 crop years.

Further Reading

American Sheep Industry Association. Fast Facts About American Wool, 2004. Available from http://www.sheepusa.org .

American Sheep Industry Association. Fast Facts About Sheep Production in America, 2004. Available from http://www.sheepusa.org .

United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service. Sheep, 18 July 2003. Available from http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/reports/nassr/livestock/pgg-bbs/shep0703.txt .

United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service. Sheep and Goats, 30 January 2004. Available from http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/reports/nassr/livestock/pgg-bb/shep0104.txt .

United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service. "Statistics of Cattle, Hogs, and Sheep." Washington, D.C.: 2002. Available from http://www.usda.gov/nass/pubs/agr01/01_ch7.pdf .

United States Department of Agriculture. USDA01: End the Wool and Mohair Subsidy, 15 January 2000. Available from http://www.npr.gov/library/reports/ .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: