SIC 1771

CONCRETE WORK

Special trade contractors primarily engaged in concrete work, including portland cement and asphalt. This industry includes the construction of private driveways and walks of all materials. Concrete work incidental to the construction of foundations and concrete work included in an excavation contract are classified in SIC 1794: Excavation Work; and those engaged in construction or paving of streets, highways, and public sidewalks are classified in SIC 1611: Highway and Street Construction, Except Elevated Highways.

NAICS Code(s)

235420 (Drywall, Plastering, Acoustical and Insulation Contractors)

235710 (Concrete Contractors)

Industry Snapshot

Concrete—a mixture of portland cement, sand, gravel, and water—is used for the construction of everything from patios and floors to dams and highways. Special trade contractors involved in concrete work provide the following products and services: private asphalt parking areas; blacktop work; concrete work for private driveways, sidewalks, and parking lots; culvert construction; curb construction; pouring concrete to build foundations; grouting work; parking lot construction; patio construction; sidewalk construction, except public; and stucco construction.

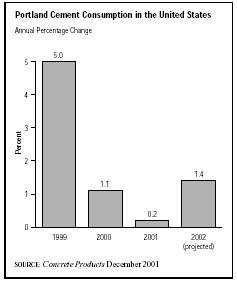

The most recent U.S. Census Bureau reports indicated that more than 30,000 establishments are involved in concrete contracting. These companies employed 190,000 cement masons, concrete finishers, and terrazzo workers in 2002, according the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Portland cement consumption declined in the Northeastern and Mountain states in 2001, due in large part to the economic recession—exacerbated by the September 11 terrorist attacks—which prompted a slowdown in commercial and industrial construction and transportation expenditures. Compared to a 5 percent growth rate in 1999, portland cement consumption grew by only 0.2 percent in 2001. However, consumption was expected to grow 1.4 percent in 2002 as every region of the United States saw gains.

Organization and Structure

The construction industry can be divided into three segments: general building contractors, heavy construction contractors, and special trade contractors, which includes those engaged in concrete work. General building contractors build residential, industrial, commercial, and other buildings, while heavy construction contractors

build structures such as roads, highways, and bridges. Special trade contractors usually focus on one trade and work under the direction of general contractors, architects, or property owners. Beyond completing their work to specification, special trade contractors have no responsibility for building the structure in its entirety.

Concrete can be classified by the type of aggregate or cement used, by specific characteristics, or by production methods. Ordinary structural concrete is characterized by its water-to-cement ratio. The lower the water content, all else being equal, the stronger the concrete. For concrete to set properly, however, the mixture needs to have enough water to ensure that the aggregate particles are encompassed by the cement paste, that the space surrounding the aggregate is filled, and that the concrete is liquid enough to be poured and spread effectively. The composition of concrete varies because different aggregates are used from market to market, depending upon what kind of sand and rock is available and least expensive.

Concrete's range of durability is determined by the amount of cement in relation to the aggregate, with relatively less aggregate present in strong cement. The strength of concrete is measured in pounds per square inch (psi) of force needed to crush a concrete sample of a given age or hardness. Concrete's strength can be affected by environmental factors, especially temperature and moisture.

Cement, through its use in concrete, is used in all types of construction. The Portland Cement Association estimated that in the mid-1990s about 55 percent of cement shipments in the United States was consumed in building construction, with 22 percent used for residential and 19 percent for commercial construction. Public works construction consumed about 42 percent of cement shipments, with most going to the building of streets and highways.

By far the largest customer for portland cement at that time was the ready-mix concrete industry, which purchased about 71 percent of the total shipments. Another 13 percent went to concrete producers of blocks, pipes, precasts, and prestressed products; 5 percent to highway contractors; 4 percent to building materials dealers; 3 percent to other contractors; and 4 percent to all others, including the government.

Background and Development

Long before the discovery of cement, ancient civilizations used clay as a bonding substance. The Egyptians used a material made from lime and gypsum that resembled modern-day cement. Derived from limestone, chalk, or oyster shells, lime continued to be the primary cementing agent until the early 1800s.

In 1824 English inventor Joseph Aspdin burned and ground together a mixture of limestone and clay. This concoction, called portland cement, became the cementing agent used in concrete from that time on.

In 1867 Joseph Monier, a Parisian gardener who made pots of concrete reinforced with iron mesh, received a patent for reinforced concrete. This product, sometimes called ferroconcrete, consisted of concrete hardened onto imbedded metal, usually steel. The reinforcing steel contributed tensile strength.

A later innovation in masonry construction was the use of prestressed concrete, which neutralized the stretching forces that would rupture ordinary concrete. Because it achieved its strength without heavy reinforcements, prestressed concrete could be used to build light, shallow structures such as bridges and roofs.

During the 1980s cement imports became a significant part of the domestic supply, peaking in 1987 at more than 17 million short tons. The reason for this rise in imports was weak worldwide demand combined with strong U.S. demand, which made the United States a target for excess supplies produced by foreign cement manufacturers. Low water transportation costs during the 1980s also was a key. Canada was the largest supplier of cement to the United States through 1985. Mexico became the primary source from 1986 through 1989, supplying 28 percent of total U.S. imports in 1989.

U.S. consumption of cement (the major component of concrete) was 84 million short tons in 1993. Cement was used to build highways and other public works and to rebuild structures damaged by natural disasters, such as the hurricane in southern Florida, the earthquake in Los Angeles, and the flood in Midwest river basins. During the mid-1990s the concrete industry benefitted from a slow but steady recovery in the housing industry. New home building traditionally used about one-third of the cement consumed annually in the United States.

Prices for concrete varied widely and depended on the proximity of the nearest mill. Transportation costs continued to be a major factor in determining costs, because concrete was so heavy and had to be delivered on a timely basis. In 1994 the U.S. Justice Department began investigating possible price fixing, since the average cost of cement had jumped from $5 to about $50 a ton within one year.

Current Conditions

New construction accounts for the lion's share of work done by concrete contractors. although firms also engage in reconstruction, maintenance and repair. Building construction includes work on single-family houses. Nonbuilding construction includes work done on private driveways and parking areas, as well as work done on projects such as highways and streets.

Ready-mixed concrete producers in North America numbered more than 2,700 in 2002. A total of 13 U.S. concrete contracts secured more than $1 billion in sales in 2002. Concrete contractors were primarily concentrated in California, Texas, and Florida. Other states with a high concentration of firms in this industry included Illinois, Michigan, Missouri, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. Concrete contractors tended to cluster around those states producing the most construction sand and gravel.

Throughout the early 2000s, the $90 billion construction industry grew rapidly as the nation experienced a surge in housing starts. The construction boom happened in spite of a sluggish economy, due in large part to historically low interest rates. For the residential building industry, 2003 was one of the best years on record. The economic conditions of the early 2000s proved to be a mixed blessing for the concrete industry. While residential construction reached levels not seen since the 1970s, commercial and industrial construction, as well as in nonbuilding sectors such as transportation, saw significant slowdowns. These declines were reflected in the growth rate of portland cement consumption, which dipped from 5 percent in 1999 to less than 1 percent in 2001. Although consumption increased by 1.4 percent in 2002, growth remained well below the 1999 level.

Industry Leaders

During the early 2000s the residential and commercial concrete industry was a mixture of large public companies, such as cement manufacturers, and small independent concrete contractors and laborers. Among the largest companise involved in the industry was Houston, Texas-based Cemex USA, Inc., which operated 85 ready-mix plants and 12 cement plants throughout the United States. Other industry leaders (those with sales of $1 billion or more) included Lafarge North America Inc. (Herdon, Virginia); Oldcastle Inc. (Atlanta, Georgia); Vulcan Materials Co. (Birmingham, Alabama); Rinker Materials (West Palm Beach, Florida); Aggregate Industries Inc. (Saugus, Massachusetts); A. Teichert and Son Inc. (Sacramento, California); Granite Construction Inc. (Watsonville, California); Lehigh Cement Co. (Allentown, Pennsylvania); and RMC Industries Corp. (Decauter, Georgia).

Workforce

Most concrete masons worked for concrete contractors or for general contractors on projects such as highways, bridges, shopping malls or large buildings such as factories, schools, and hospitals. A small number were employed by firms that manufactured concrete products. Fewer than 1 out of 10 concrete masons were self-employed, a smaller percentage than in other building trades. Most self-employed masons specialized in small jobs, such as driveways, sidewalks, and patios.

Cement masons and concrete finishers earned an average hourly wage of $14.74, while terrazzo workers earned $13.42 per hour. Many workers in this industry tend to work overtime, because a job must be completed once the concrete has been placed. Overtime tends to be paid at premium rates.

As the construction industry boomed, contractors had trouble finding enough workers and building supplies. The widespread labor shortage ran from 1997 into the early 2000s. To attract workers, companies increased wages and overtime pay, but many were nevertheless forced to settle for laborers who were inexperienced or insufficiently trained. The shortage of workers stemmed from a trend among young people to attend college instead of entering the skilled trades. In addition, many construction workers had left the industry during the slump of the early 1990s.

Concrete masons generally learned their trade through on-the-job training or apprenticeship programs. Many concrete workers belonged either to the Operative Plasterers' and Cement Masons' International Association of the United States and Canada or to the International Union of Bricklayers and Allied Craftsmen.

Research and Technology

The future of the concrete industry lay in continued development of high-performance concrete products. Since the start of the 1980s, concrete formulations changed to create an entirely new generation of high-strength products. What was once considered strong was 7,000 to 9,000 psi, but new products reached 15,000 to 20,000 psi. These concrete products became popular for use in tall buildings, bridges, offshore structures, and pavements.

Further Reading

Kuennen, Tom. "2002 Forecast." Concrete Products, December 2001.

Rehana, Sharon J. "Construction Pours It On; Despite an Economic Slowdown, the Concrete Industry Continues Its Slow But Steady Growth." The Concrete Producer, October 2003.

U.S. Department of Commerce. Census Bureau. Economic Census 1997. Washington, DC: GPO, 2000. Available from http://www.census.gov/prod/ec97/97c2357a.pdf .

U.S. Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2004-05. Washington, DC, 2004. Available from http://www.bls.gov/oco/print/ocos203.htm .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: