SIC 3149

FOOTWEAR, EXCEPT RUBBER, NOT ELSEWHERE CLASSIFIED

This classification includes establishments primarily engaged in the production of shoes, not elsewhere classified, such as misses', youths', boys', children's, and infants' footwear and athletic footwear. Establishments primarily engaged in the manufacture of rubber or plastics footwear are classified in SIC 3021: Rubber and Plastics Footwear, and those manufacturing orthopedic extension shoes are classified in SIC 3842: Orthopedic, Prosthetic, and Surgical Appliances and Supplies.

NAICS Code(s)

316219 (Other Footwear Manufacturing)

Industry Snapshot

The nonrubber footwear industry manufactures all types of footwear except rubber protective and rubbersoled fabric upper (the traditional "sneaker"). Nonrubber footwear may be constructed with leather, vinyl, plastic, or textile uppers or combinations of these materials for all ages and both genders. Men's footwear producers, classified in SIC 3143: Men's Footwear, Except Athletic, and women's footwear producers, classified in SIC 3144: Women's Footwear, Except Athletic, compose their own independent industries.

The main categories of nonrubber footwear include athletic shoes, outdoor shoes (such as boots), and safety footwear. The safety footwear segment includes heavy leather work boots with steel toes for extra protection. U.S. consumers purchase more than 1.3 billion pairs of shoes a year, spending nearly $50 billion. Sales in the footwear industry are influenced by economic conditions, demographic trends, and pricing. Fashion trends generally play a limited role in overall market demand. Since 1993, consumers shifted away from designer brands and became more price conscious. With more companies allowing casual dress, the demand for dress shoes declined. In addition, consumers increasingly chose "brown shoes," which are rugged, yet comfortable, instead of athletic shoes for casual wear.

Because of lower manufacturing costs and modified trade rules, most footwear (or the parts requiring the most labor) was produced in Mexico, Central America, and Asia during the late 1990s and early 2000s and, consequently, employment in U.S. footwear factories plunged. Between 1967 and 2001, a total of 775 U.S. shoe plants shuttered operations. Automation also contributed to the decline.

During the same period, unit sales of shoes declined, although dollar sales increased slightly. Price increases for men's, women's, and infants' shoes contributed to the sales increases. Lower-priced shoes and athletic footwear dominated the market. To improve market share, manufacturers consolidated, increased marketing, and opened their own retail stores. Some also increased sales operations abroad; demand in some countries, however, was lessened by the Asian economic crisis, which lasted into the early 2000s.

Background and Development

According to Footwear News, shoe style cycles have historically "averaged two years in ascendancy, two years at peak, two years in descendency." Those averages held for various popular styles—such as loafers, platforms, and dress boots—and their design characteristics until athletic footwear manufacturers captured nearly one-third of the total footwear market in the early 1970s. Over a span of more than 25 years, American consumers spent $300 billion on 7.5 billion pairs of athletic shoes. Athletic shoe companies built empires by spending huge sums on innovative marketing strategies that included sports-celebrity endorsements and advertising and promotion with tie-ins to college and other sports. Reebok International Ltd. and adidas became $3.5 billion companies, while Nike Inc. became the first-ever $9.5 billion company. In 1998, however, athletic footwear for casual wear began to lose out to leather boots and more rugged casual footwear, and companies started to downsize, reduce inventories and production, and trim their advertising and celebrity endorsement budgets.

In 1987 there were 120 companies operating 129 establishments in this industry. In 1992, that number had gone down to just 84 companies operating 94 establishments. By 1996, the number of establishments had dropped to about 52, with 12 factories closing since 1995. Many of the plants that closed in the early 1990s were owned by the largest manufacturing and retailing companies, which opted to source more footwear from less expensive producers overseas. In 1996 total employment declined about 11 percent to 46,100; production employment also declined by about the same amount.

As a group, the nonrubber footwear industry reported a 2.6 percent decline in shoe production in 1996 from 1995 figures, and recorded a 19.5 percent decline in profits. The two largest athletic footwear producers, however, were responsible for 94 percent of the group's total profits. Four companies, including the third-largest athletic footwear producer, recorded losses in 1992.

In 1994, shipments of footwear began to steadily decline, dropping approximately 24 percent to 19 million pairs in 1995. The value of these shipments decreased 68 percent from 1994 to an estimated $139 million in 1996. Shipments of footwear in this group accounted for 15 percent by quantity and 7 percent by value of all categories of footwear sold. Production of all types of footwear within this industry fell in 1996, dropping by an annual rate of 3 percent over the previous five years.

More than half (56 percent) of the nonrubber footwear produced in the United States had leather uppers in 1996. This was up from 51 percent in 1991. Only 31 percent of juvenile types of shoes had leather uppers, while almost all athletic footwear had leather uppers.

Ups and Downs of Personal Consumption. Historically, consumers have primarily purchased their footwear at footwear specialty stores and department stores. In the past, customers were strongly brand-loyal and most often selected footwear purchases on the basis of brand recognition and style. During the 1980s, consumers took great interest in their appearance and became slightly extravagant at the sales counter. Personal consumption of footwear and other apparel nearly doubled, with an average annual growth rate of 7.3 percent. Hurt by a recession, weak growth in disposable income, and high unemployment, however, consumers in the early 1990s became much more frugal.

Along with these economic changes came changes in consumer psychology. Designer names, high-priced shoes and apparel, and frequent shopping sprees became things of the past in 1993, as consumer tastes in general shifted away from designer brands. Consumers became more value conscious and began purchasing less expensive products at lower-end retail establishments, such as mass merchandisers, stores in strip shopping centers, and outlet stores. Department stores' share of all apparel expenditures fell to 24.3 percent in 1993, down from 33.6 percent in 1985, as women were buying more of their families' shoes and other apparel at mass merchandisers, such as Kmart and Wal-Mart, and shopping less frequently at department and specialty stores.

In addition to opting for different types of retail establishments, shoppers also were selecting different types of merchandise by the early 1990s. Basic footwear and moderately priced brand-name shoes were often the best selling items. This pattern reflected a more value-oriented consumer, as well as an aging population seeking comfort and less formality in footwear. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, many mass merchandisers added more recognizable national brand names to their in-store inventory. Previously, most brand names were distributed only through department stores.

During the 1990s, formal attire lost some of the popularity it had enjoyed in the 1980s, and footwear sales reflected this trend. A decrease in the size of the white-collar work force and a trend toward more relaxed office attire contributed to a slide in the sale of formal footwear.

Acquisitions and Consolidations. Throughout the late 1980s, the 10 largest publicly traded apparel companies saw their market share increase by nearly 5 percent. Part of this growth was attributed to increased demand for these companies' products, but a series of acquisitions and consolidations was also beneficial. This consolidation of the footwear manufacturing industry paralleled developments in the retail industry as a whole. As large department store retailers merged in the late 1980s, they consolidated their buying functions. Larger apparel and footwear manufacturers benefited from this because it became more efficient for the fewer number of buyers to use one vendor rather than several. In response, growth-oriented apparel and footwear manufacturers increased their acquisition activity in search of new brands and broader product offerings.

In addition, the enormous growth of large mass merchandisers drove the industry to consolidate. From 1981 through 1991, Sears, Roebuck and Co.—then the nation's largest retailer—saw its sales increase rapidly, as did Wal-Mart and Kmart. Savvy footwear manufacturers understood they could increase their sales and market share by offering these retail giants a broad array of brand-name merchandise. Historically, many brand-name manufacturers sold their goods only to department stores; as time went on, however, they sold nearly identical merchandise to mass merchandisers in order to participate in that sector's phenomenal growth. Not surprisingly, this affected manufacturers' relationships with department stores, which sought exclusivity in their products. To remedy the situation, many manufacturers began to produce several different categories of brand names, each of which was distributed through a different type of retailer.

Throughout history, retailers and footwear manufacturers have had an adversarial relationship because of issues centered around pricing. In the mid-1990s, pricing was still an important factor, but retailers also wanted special services from manufacturers. Storage of inventory was one of the highest expenses a retailer faced. To reduce this expense, more and more retailers demanded that manufacturers carry the inventory instead and make deliveries when the retailers' stock was low. In order for this type of relationship to work, especially when dealing with large quantities of merchandise required by stores such as Wal-Mart or Kmart, retailers and vendors found it necessary to form partnerships. Quick response was the most important aspect of this relationship. Orders had to be replenished automatically via computer links called electronic data interchange.

Retailers also demanded a continual flow of new merchandise. Some footwear manufacturers responded to this need by creating "flow replenishment" programs, in which new products were introduced in a continual flow rather than in seasonal batches. In addition, retailers were demanding more marketing support and other services. Many manufacturers, as a result, created their own point-of-sale fixtures and advertised their products nationally.

Experts traced the growing appeal of outlet stores back to the value-conscious shopper. The primary attraction of outlet stores was the price of their products. Customers generally purchased footwear and other apparel items at up to half the cost charged by conventional department and specialty stores. In many cases, the merchandise offered was no longer just the irregulars, over-runs, or odd lots; often, the merchandise was first quality, coming from current inventory. Many footwear manufacturers, however, used their own outlet stores to dispense extra or second-quality merchandise. Manufacturers preferred this form of distribution to off-price retailers because they could avoid tarnishing their brand names. Risk to brand names often occurred when too much merchandise was sold through discounters. In addition, outlet stores also tended to be located far from the selling areas of conventional department and specialty stores. This decreased the chance that the manufacturer's regular retail store would lose sales to the outlet store.

Athletic Footwear. Athletic footwear was the largest selling category in the footwear industry, and the only division within nonrubber footwear to post any gains in the mid-1990s. Production of athletic footwear reached a peak of about 6.5 million pairs in 1993, but declined to 5.5 million pairs in 1995. Consumption of athletic footwear, which included imports, rose from a 1993 total of 382 million pairs to 408 million pairs in 1995. Representing 99 percent of consumption, imports continued to dominate the market, while U.S. production continued to decline. Imports have risen by an average of 3.5 percent per year since 1990. Even though the number of shoes purchased declined, the sales of athletic shoes actually increased, to $11.4 billion. Athletic footwear represented about 26 percent of combined nonrubber and rubber-fabric footwear consumption of approximately 1.6 billion pairs in 1995. Imports of juvenile footwear in 1996 were down from 1995 but were still higher than any previous year; similarly, imports of athletic nonrubber footwear increased from 1995 but were still lower than any other year in the early 1990s.

The largest selling and most consistently popular brand of athletic footwear was from Nike—men bought Nike 70 percent of the time, while women purchased this brand 61 percent of the time. Reebok was not far behind, and was in fact the only brand that gave stiff competition to Nike. Reebok International Ltd.'s shoes represented 46 percent of purchases for men and 57 percent of purchases for women. Adidas, Converse, and Fila rounded out the top five brands, but none had more than 23 percent of purchases.

The Summer Olympics of 1996 gave the top athletic brands a chance to compete with each other for sponsorship and advertising rights. The general target audience was 18-to 34-year-olds, and marketers reached them with a mix of sports, lifestyle television programming, and magazine titles. While Nike, Converse, and Avia built strong followings in the performance shoe business, Reebok and L.A. Gear had more of a fashion than a performance-based image. Nike, though not an official sponsor of the Olympic games, led the way by spending more on advertising, and in fact, many people believed they were a sponsor. Reebok teamed with The Athlete's Foot in downtown Atlanta to show off "Planet Reebok," hoping to cash in on its proximity to the athletes and spectators. Most athletic shoe companies relied on high-priced, prime time television advertisements and major sporting event television advertisements for most of their media advertisements.

The nation's largest selling footwear company, Kinney Shoe Corp., launched its own private label of athletic footwear in August 1993 through its Foot Locker sneaker and sports apparel retail chain. The new shoe brand, In the Zone or ITZ, had its own independent marketing budget and was set to compete with the volatile second tier of athletic shoe brands, such as L.A. Gear, adidas, Converse, and Asics.

Outdoor Footwear. One of the fastest growing categories in the footwear industry during the mid-to late 1990s was outdoor footwear. Outdoor footwear includes rugged hiking boots and casual outdoor sandals. In 1995, hiking boot sales exploded, selling 27 million pairs over the course of that year, compared with just 22 million in 1994 and 11 million in 1992. Sales grew 14 percent to top one billion dollars for the first time. Sales grew in spite of an average price drop in hiking boots, going from around $42 a pair to just $38 a pair. Many traditional athletic footwear companies recognized the potential profit in this category and were scrambling to participate.

In the athletic outdoor shoe category, Teva sandals, manufactured by Deckers Outdoor Corp., were one of the most popular styles of outdoor sports sandals in the 1990s. Sales for 1996 dropped by less than 1 percent to $102 million as the market was flooded with imitation Tevas and a wide array of sports sandals from all the major athletic shoe companies. After the initial excitement waned, however, consumers went back to the original, and Deckers'first quarter sales for 1997 increased 20 percent over first quarter 1996, with sales of Tevas increasing by 30 percent.

One of the fastest growing companies in the outdoor shoe category was Timberland Co. In addition to streamlining its operations, Timberland cultivated the casual outdoor fashion that began to increase in popularity in the early 1990s. Sales increased by 125 percent since 1992, reaching $655 million in 1995. Many companies were attempting to imitate Timberland's style, but consumers still considered Timberland to be the "original."

Safety Footwear. Safety footwear constituted yet another segment of the footwear industry. This type of footwear was worn mainly by workers with hazardous, physically demanding jobs. In the mid-1990s, safety footwear started to look much more like mainstream retail footwear. Workers who cared as much about style and comfort as they did about protection, and were more inclined to wear shoes that were aesthetically pleasing, drove the trend. The most successful safety footwear manufacturers were designing shoes that combined a safe environment for the foot with an overall stylish appeal.

Juvenile Footwear. After many years of rapid growth due to the heavy sales demands of the postwar baby-boom era, juvenile footwear sales slowed in the early 1990s. Despite reaching the peak of the baby boom, competition among this category's competitors was still tight. Production of juvenile footwear steadily declined through the 1990s, dropping below 10 million pairs for the first time ever, in 1996.

The undisputed leader in juvenile footwear was Stride-Rite Corp. In 1993, after 27 consecutive quarters of increased earnings, company sales started dropping from $585 million in 1992 to $448 million in 1996. Stride-Rite's primary competition in the juvenile footwear industry included Keds (a brand also owned by Stride-Rite), Weebok (owned by Reebok), Sebago, Sam & Libby, and Toddler University. As in the case of adult footwear, the industry witnessed a trend away from shopping at higher-priced department stores and specialty-shop retailers, toward lower priced mass merchandisers and outlet stores. Also, with more two-career families, parents were finding less time to take children shopping. As a result, the industry witnessed a trend toward direct-mail purchasing through catalogs.

New Markets. With limited prospects for domestic growth, many footwear companies in the early 1990s were looking for growth opportunities abroad. For footwear merchandise, market penetration was limited since tastes in fashion apparel differed from one country to the next; every country in the world, however, looked to sell in America, the world's leader in footwear consumption. China's exports to the United States grew 2,600 percent since 1986, at an average rate of 40 percent annually. In 1996, China exported 750 million pairs of shoes; Brazil was the second largest exporter to the United States, shipping over 91 million pairs. The import penetration rate ballooned, going from around 40 percent in 1976 to more than 90 percent for the first time in 1996.

Overall exports in nonrubber footwear improved, shipping just under 25 million pairs in 1996. Athletic shoes improved slightly, while exports in slippers (which included the sports sandal) tripled from 1995, going from 607 million pairs to 1.8 billion pairs in just one year. Juvenile footwear also showed strong international sales in 1996, almost doubling its 1995 showing, increasing to five million pairs. Japan enjoyed its second year as the main importer of U.S. footwear, taking the mantle from Canada in 1995. Exports to Japan totaled 3.6 million pairs in 1996, while Canada took 2.4 million pairs. The U.K. market continued to grow, importing 1.6 million pairs, and Mexico imported 1.1 million pairs of U.S. footwear.

Many manufacturers believed that basic footwear, such as tennis shoes and children's shoes, had the potential for a large international market. Many brand-name products, such as Nike, became major international franchises in the mid-1990s. In 1996 international sales accounted for 36 percent of Nike's total sales of $6.4 billion. Total worldwide orders for athletic footwear were $3.9 billion in 1996 compared to only $2.5 billion in 1995. Such rapidly rising worldwide sales were especially important to Nike as it struggled to overcome slow growth in the United States. In China, Nike found that its challenge was to get its shoes into stores and ensure that those stores knew how to display products that were extremely expensive by Chinese standards. In the Philippines, 20 percent of Nike's shoe sales were made by door-to-door salespeople who sold the shoes on credit. Keeping control of its distribution operation and remaining flexible in the face of cultural differences were keys to boosting Nike's sales in the region. Nike gained control of its distribution in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Malaysia, China, Singapore, Australia, and New Zealand within a three-year period. Nike executives spoke of creating an emotional tie with the consumer in these countries, and as a result, Nike was one of the world's most recognized brand images in the 1990s and was the world's largest supplier of athletic footwear.

Timberland Co. also was successful in exporting its footwear. In 1983, the company had no interest in foreign markets; 13 years later, nearly 30 percent of its business came from overseas markets, and Timberland owned franchises and retail stores for its products in 50 countries. Timberland's executives developed an interest in the export business when they joined forces with an Italian consumer goods distributor to establish European operations. Once there, they learned that international marketing campaigns needed to be country specificto succeed. Timberland became very sensitive to cultural differences and won many European customers by developing new flexible marketing techniques, which included "concept shops," "specialty shops," and filling retailers orders quickly.

Current Conditions

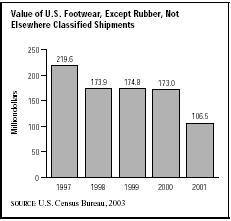

U.S. production of nonrubber footwear declined steadily in the late 1990s and early 2000s. From 1997 to 2001, the value of industry shipments declined from $219.6 million to $106.5 million. The largest declines were in the slippers and women's footwear categories. Athletic footwear manufacturers also were experiencing declines as teens and young adults began purchasing boots and other brown shoes for casual wear.

Industry employment fell along with production. In 2000 total nonrubber footwear industry employment fell to 2,047, compared to 3,327 in 1997. This drop followed declines of 9 percent in 1997, 15 percent in 1996, and 9 percent in 1995. The number of U.S. shoe manufacturing plants declined by 775 between 1967 and 2001. At the same time, the number of new plant openings dwindled to nearly zero.

Although U.S. production declined, U.S. consumption increased from 1.2 billion pairs in 1997 to 1.3 billion pairs in 2001. The per capita consumption was about 4.9 pairs, up from 1997, but still below the levels of the 1980s when athletic footwear boosted demand above five pairs. Imports accounted for 98 percent of nonrubber footwear consumption by the early 2000s. Fewer than one in 20 pairs of shoes sold in the United States were manufactured domestically.

In 2003 imports of nonrubber footwear from China, the leading supplier to the United States, increased by 6 percent to 1.26 billion pairs. China's share of the U.S. footwear import market grew from 67 percent in 1998 to 81.4 percent in 2003. Brazil, the second-leading supplier, saw its imports increase 2.3 percent to 83.5 million pairs in 2003. Imports from Vietnam jumped 91.9 percent to 23.5 million pairs in 2003. As a result, the nation became the fifth-largest supplier of footwear to the United States. Mexico, the Philippines, and Taiwan are other leading U.S. imports suppliers.

In the mid-2000s, per capita consumption of nonrubber footwear was expected to remain steady; the U.S. market would continue to be dominated by imports from countries with low-cost labor. These foreign producers

would also provide stiff competition for U.S. footwear manufacturers, most of whom had shifted operations overseas to take advantage of cheaper labor.

In was this environment that prompted the American Apparel and Footwear Association, which had once been vehemently opposed to the growing levels of imports, to begin calling for the elimination of tariffs on nonrubber footwear imports. As stated in a June 2002 issue of Footwear News , "In a dramatic reversal that reflects the changed character of the domestic footwear business, the American Apparel & Footwear Association has shifted its international footwear trade policy to vigorously support free trade."

Industry Leaders

According to Standard & Poor's, the top footwear companies are Brown Group, Justin Industries, K-Swiss Inc., Nike, Nine West Group Inc., Reebok International, Stride-Rite Corp., Timberland Co., and Wolverine World Wide. K-Swiss sells tennis shoes, children's shoes, and sports sandals, which are manufactured by independent suppliers and sold in specialty retail stores in more than 50 countries. Nine West Group sells women's casual, career, and dress footwear under the Nine West, Easy Spirit, Bandolino, Enzo Angiloini, and Pappagallo brands, and the licensed Calvin Klein label.

The largest shoe company in the world, Nike holds a 20 percent share of the U.S. athletic-shoe market. The company makes shoes for numerous sports and operates Niketown shoe and sportswear stores. Selling its products in 110 countries and online, it posted an 8.1 percent increase in 2003 sales, which reached $10.6 billion, despite the trend of teens and young adults toward brown shoes for casual wear. Reebok, the second largest maker of athletic shoes, which also made Rockport walking and casual shoes, saw sales in 2003 increase 11.4 percent to $3.48 billion.

Stride-Rite Corp. was a designer and marketer of casual and athletic footwear for adults and children. Brands included Grasshoppers, Keds, Munchkin, Pro-Keds, Sperry Top-Sider, Street Hot, and Stride-Rite.

The Timberland Co. made waterproof hiking boots, boat shoes, dress and outdoor casual shoes, and sandals. Wolverine World Wide was the producer of Hush Puppies casual shoes, slippers, and boots, and of Merrell outdoor boots, Bates military boots, and Hy-Test and Wolverine industrial boots. It also produced Caterpillar, Coleman, and Harley-Davidson branded footwear.

Other footwear companies included Red Wing Shoe Co., Inc.; New Balance Athletic Shoe, Inc.; Skechers U.S.A., Inc.; and Deckers Outdoor Corp. Red Wing first made its Red Wing brand work shoes designed for specific occupations in the United States in 1905. The company outsourced its Vasque, Irish Setter, and WORX brands. New Balance made its athletic shoes for men and women in the widest selection of shoe widths. It also made children's shoes. Skechers was a leader in casual footwear aimed at 12-to 25-year-olds. Its 900 styles of oxfords, boots, sneakers, sandals, and semi-dressy shoes resulted in a nearly 103 percent rise in sales in 1998. Deckers Outdoor was the marketer of the Teva sports sandal, Simple casual and athletic footwear, and Ugg sheepskin boots.

Research and Technology

Like most industries, manufacturers in the nonrubber footwear industry were under extreme pressure to limit the size of their work force, while boosting productivity and efficiency at the same time. For that reason, the industry considered new technology essential to increase growth and profitability. In the 1970s and 1980s, the use of computers integrated design, manufacturing, management, and marketing tasks. Computerized production allowed manufacturers to emphasize nonprice factors such as quality and quick delivery to compete with imports.

Many footwear producers turned to computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) systems and software. As a result, these manufacturers produced tooling from CAD-generated data and linked it to auto-stitchers, milling, and turning machines. In the early 1990s, the industry witnessed a resurgence of interest in three-dimensional CAD, which produced more accurate shoe patterns and reduced the number of prototypes required to take a new shoe design to the retail level. By the late 1990s, CAD systems enabled athletic footwear manufacturers to put a new design into production within a few months.

In the footwear industry, computers also enabled manufacturers to combine several operations or machines under fewer operators, thereby reducing handling time and the number of employees, while improving quality. The industry also developed computerized robots to handle and transfer operations within and between production modules.

In order to meet the demands of retailers' quick response requirements, more and more manufacturers were utilizing electronic data interchange (EDI). The goal of quick response was to maintain lean inventories and avoid overstocking, while ensuring that retailers had the merchandise customers wanted to buy. EDI allowed retailers and manufacturers to link themselves together.

In the EDI system, interlinked computer systems were placed at every point of the manufacturing and sales process. Through use of an electronic scanner and bar code tagged to the merchandise, retailers recorded which type of footwear was sold at the point of sale. All sales data on the individual products, including details of color and size, were transmitted immediately to the manufacturer. Through this method, the manufacturer kept track of every store's retail sales trends. This first-hand view of consumer purchasing trends allowed manufacturers to produce apparel based directly on customer demand. The information contained in the bar code set automatic reordering into motion. The industry also referred to this type of inventory replenishment as "flow" or "just in time." In addition to allowing automatic replenishment, EDI also ameliorated distribution and shipping processes. For example, once a shipment was ready to go, the manufacturer created a labeling document, and EDI sent an invoice automatically.

A great deal of this new technology was developed and used in Europe before coming to the United States. Most of it was easily transferred to Far Eastern footwear producers, depending on the availability of capital. For these Far Eastern manufacturers, however, the labor saving benefits of this new technology were not as great as for producers with higher production costs. Industry experts predicted that the net effect of such technology would reduce the costs of U.S. production relative to Far Eastern production, although the latter would continue to maintain a competitive advantage for most categories of footwear.

Further Reading

Ellis, Kristi. "AAFA Joins the Call for Free Trade." Footwear News, 24 June 2002.

——. "U.S. Footwear Imports Saw Improvement in 2003." Footwear News, 12 January 2004.

Siekman, Philip. "The Last of the Big Shoemakers." Fortune, 30 April 2001.

U.S. Census Bureau. "Statistics for Industry Groups and Industries: 2000." February 2002. Available from http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/m00as-1.pdf .

——. "Value of Shipments for Product Classes: 2001 and Earlier Years." December 2002. Available from http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/m01as-2.pdf .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: