SIC 3229

PRESSED AND BLOWN GLASS AND GLASSWARE, NOT ELSEWHERE CLASSIFIED

This category includes establishments primarily engaged in manufacturing glass and glassware, not elsewhere classified, pressed, blown, or shaped from glass produced in the same establishment. Establishments primarily engaged in manufacturing textile glass fibers are also included in this industry, but establishments primarily engaged in manufacturing glass wool insulation products are classified in SIC 3296: Mineral Wool. Establishments primarily engaged in manufacturing fiber optic cables are classified in SIC 3357: Drawing and Insulating of Non-ferrous Wire; and those manufacturing fiber optic medical devices are classified in the surgical, medical, and dental instruments and supplies industries. Establishments primarily engaged in the production of pressed lenses for vehicular lighting, beacons, and lanterns are also included in this industry, but establishments primarily engaged in the production of optical lenses are classified in SIC 3827: Optical Instruments and Lenses. Establishments primarily engaged in manufacturing glass containers are classified in SIC 3221: Glass Containers, and those manufacturing complete electric light bulbs are classified in SIC 3641: Electric Lamp Bulbs and Tubes.

NAICS Code(s)

327212 (Other Pressed and Blown Glass and Glassware Manufacturing)

Industry Snapshot

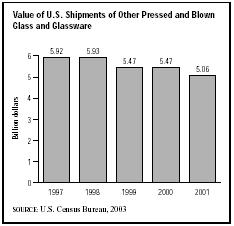

The pressed and blown glassware industry manufactures products ranging from television tubes, ashtrays, candlesticks, stemware, tobacco jars, and optical lenses to Christmas tree ornaments. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the industry maintained a steady level of employment at about 37,000 workers, while the value of shipments rose steadily to reach $5.9 billion by 1997. However, by 2001, employment had fallen to 29,241 workers and the value of industry shipments was down to five billion dollars.

Organization and Structure

The companies involved in the pressed and blown glass industry displayed much diversity in earnings and employment levels. Of the roughly 500 industry establishments in the early 2000s, only about 20 percent employed 20 or more people. However, the industry was dominated by large companies related in some way to Corning Incorporated, such as Owens-Corning, Owens-Illinois,

and Owens-Corning Fiberglass. Anchor Hocking Glass (a division of Newell Rubbermaid Inc. until April of 2004, when it was sold to Global Home Products LLC) was another giant in the industry, although dwarfed by the Corning units. Steuben Glass, also a Corning company, and Lenox Crystal were among those companies making handmade stemware, both of which shared the international market with Waterford Crystal of Ireland.

Due to the resurgence of interest in glass blowing in the United States, small craft shops could be found across the country where artisans sold their wares, displayed their techniques, and often taught classes. However, these shops were generally neither involved nor interested in producing the mass quantities of machine-made glassware supplied by such large corporations as the Corning conglomerate.

The product share within the industry was split between five types of goods in 2001. Textile glass fiber accounted for 30 percent of the overall market; machinemade table, kitchen, art, and novelty glassware claimed roughly 17 percent; machine-made lighting and electronic glassware took another 31 percent; all other machine-made glassware accounted for about 17 percent; and handmade pressed and blown glassware claimed approximately 3 percent. The materials consumed in the greatest amounts by the industry included all types of glass sand; sodium carbonate (soda ash); industrial organic chemicals other than sodium carbonate; other chemicals and allied products; and wood boxes, pallets, skids, and containers.

Background and Development

The Mesopotamians are credited by archaeologists with making the world's first glass, circa 2500 B.C. However, it was not until the Roman Empire that glass making evolved as a standard craft, much like baking and jewelry making. Venice eventually became known as the glass making capital of the world and remained so through the 1600s. Glass making in the United States was very much a crude art form until the eighteenth century, but it nearly died out several times. Glass items of any quality, such as windows or glassware, needed to be bought from England. However, several small shops where glass was blown provided wares for limited customer bases, and eventually larger manufacturers, such as Bakewell and Company of Pittsburgh, entered the marketplace. For the cosmetic enhancement of glass, etching was practiced during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. However, the ability to press glass in very large quantities did not develop until the nineteenth century.

The glass industry in the United States started to boom after the War of 1812. Between 1800 and 1825, America experienced strong demographic, economic, and political growth. Luxury items were in ever-increasing demand, creating a need for machine-made glass products. Glass pressing was already common in Europe by the late 1700s, although the pieces were small and made with waffle-iron-type presses. American inventors developed the first large, hand-operated pressing machine.

The introduction of glass pressing created a new challenge for glassmakers. Only specific glass mixtures were adequate for pressing, which required experimentation. Also, experience was required to know how much molten glass could be placed in a press without scrapping the piece and how much time was required to produce the glass before it started to cool and crack. By the time these processes were perfected, glassmakers started to produce molds exhibiting ornate designs, referred to as "lacy glass." Glass pressing continued to evolve during the colonial era, expanding to candlesticks and lamps. The Victorian era heavily influenced glass making, and by the 1880s, colored glass was the order of the day. Glass collecting became a pastime for many and an obsession for some, evidenced by collectors willing to pay heavily for early American, lacy, carnival, and depression glassware.

Current Conditions

The pressed and blown glass industry in the late 1990s and early 2000s experienced low margins, high competition, and high technology. While glass tableware and cooking dishes did not share the high-tech image of fiber optic cables and devices, research and development continued for better materials for these purposes. Likewise, new marketing approaches, such as creative packaging and merchandising, were constantly investigated.

Industry shipments declined from $5.9 billion in 1997 to $5 billion dollars in 2001. Each of the industry's five segments saw declines during this time period. For glass fiber, textile-type, the value of shipments dropped from $1.9 billion in 1997 to $1.5 billion in 2001. Shipments of machine-made pressed and blown table, kitchen, art, and novelty glassware fell from $989.3 million to $859.3 million; machine-made pressed and blown lighting, automotive, and electronic glassware, from $1.7 billion to $1.5 billion; all other machine-made pressed and blown glassware, from $960.1 million to $851.5 million; and handmade pressed and blown glassware, from $173.9 million to $131.4 million.

Industry Leaders

In the 1990s, many of the top-ranking companies in the entire glass industry were related in some fashion to Corning Inc., of Corning, New York—Owens Corning and Owens-Illinois Inc., both of Toledo, Ohio, and Corning Consumer Products Co. of Elmira, New York.

Corning Inc. posted 2003 revenue of about $3.1 billion, slightly less than revenues in 1998. The company, with more than 20,600 employees worldwide, changed its name in 1989 from Corning Glass Works to better reflect its increasingly diverse product line. The founder, Amory Houghton, moved his glass operation from Brooklyn to Corning, New York, in 1868. By 1875, Corning Glass Works was incorporated, and Houghton became president of the company—a position he retained until 1911.

The technical expertise of the company was recognized early, as Thomas Edison asked for its help in making electric light bulbs in 1880. In 1912, Corning invented borosilicate, which was used to produce Pyrex in 1915. Pyrex immediately became standard in the scientific community for laboratory equipment, although the consumer markets were not tapped until years later. Another significant milestone for Corning was the 1934 manufacture of a 200-inch diameter mirror for the Mount Palomar telescope. The company surpassed this accomplishment by creating the world's largest single-piece telescope mirror for the Japanese government in 1992. In the 1960s, Corning created the ceramic heat-resisting reentry shields and glass windshields for the Apollo moon program. The most significant research for Corning in past years was in the development of fiber optics. Corning realized the potential of the material in the 1960s and continued research and development even though market demand was low and, by 1984, the company invested $87 million in new fiber optic plant facilities.

Owens-Illinois Inc., with nearly 29,800 employees worldwide in the early 2000s, was a leader in the manufacture of glass containers and other glass products, as well as a major producer of plastic packaging materials. Headquartered in Toledo, Ohio, the company posted 2003 sales of $6.1 billion, up 8.3 percent from the previous year. Owens Corning, a major producer of glass fiber, employed 18,000 people worldwide and reported 2003 sales of $4.9 billion, up 2.5 percent from the previous year. WKI Holding Company Inc., formerly known as Corning Consumer Products Co. reported 2003 revenue of $609 million, nearly 11 percent less than 2002.

Other leaders in the industry included Anchor Hocking Glass, of Lancaster, Ohio, and Libbey Inc., of Toledo, Ohio. Anchor Hocking traces its roots back to 1905, when founder Ike Collins convinced a group of seven investors to contribute to the Hocking Glass Company's original capitalization of $25,000. By the end of its first year of manufacturing and marketing lamp chimneys and other glass items, the company had generated sales of $20,000. By 1919, Hocking boasted 300 employees (many of them highly skilled glass blowers) and $900,000 in annual sales, and it had diversified from lamp chimneys (which were made obsolete by the invention of the incandescent light bulb) into glass tableware.

Acquisitions and mergers expanded the company's interests into glass containers, plastics, and hardware, increasing annual sales to a peak of more than $900 million in the early 1980s, but intense competition forced Anchor Hocking to sell out to the Newell Company (renamed Newell Rubbermaid Inc. in 1999 after its acquisition of Rubbermaid) in 1987. In April of 2004, Newell Rubbermaid sold Anchor Hocking to Global Home Products LLC.

With more than 2,460 employees worldwide, Libbey Inc. is a leading producer of glassware, flatware, and ceramic dinnerware, all of which are distributed throughout North America and to more than 100 other countries. In 2003, the company posted revenues of $609 million, down 11.1 percent from the previous year.

Workforce

In 2000, the pressed and blown glass industry employed a total of 35,009 workers—with 29,241 working in production. In 1982, 37,600 people had worked in the industry—78 percent as production workers. The average hourly wage had increased to $16.38 by 2002, up from $15.42 in 1997, and from $9.41 in 1982.

Projections for occupations in the glass industry were not bright early in the twenty-first century. All industry employees—with the exception of extruding and forming machine workers, who were expected to increase about 22 percent—were expected to decrease in numbers by 33 to 51 percent by the year 2005.

Further Reading

U.S. Census Bureau. "Statistics for Industry Groups and Industries: 2000." February 2002. Available from http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/m00as-1.pdf .

——. "Value of Shipment for Product Classes: 2001 and Earlier Years." December 2002. Available from http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/m01as-2.pdf .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: