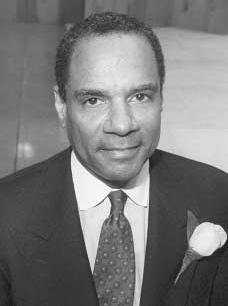

Kenneth I. Chenault

1951–

Chairman and chief executive officer, American Express Company

Nationality: American.

Born: June 2, 1951, in New York, New York.

Education: Bowdoin College, BA, 1973; Harvard University Law School, JD, 1976.

Family: Son of Hortenius Chenault (dentist) and Anne Quick (dental hygienist); married Kathryn Cassell (nonpracticing attorney); children: two.

Career: Rogers & Wells, 1977–1979, attorney; Bain & Company, 1979–1981, management consultant; American Express Company, 1981–1983, director of strategic planning; American Express Travel Related Services Company, 1981–1996, vice president, then senior vice president; 1986–1988, executive vice president of platinum/gold card; 1988–1989, executive vice president of personal-card division; 1990–1993, president of consumer-card and financial-services group; 1993–1995, president; American Express Company, 1995–1997, vice chairman; 1997–2000, president and COO; 2001–, chairman and CEO.

Address: American Express Company, World Financial Center, 200 Vesey Street, 50th Floor, New York, New York 10281-1009; http://www.americanexpress.com.

■ One of just four African American CEOs of Fortune 500 companies in 2004, Kenneth I. Chenault was a leader by example and an executive who focused on performance day in, day out. As the head of American Express Company (AMEX) he reenergized his company's brand, increased its market share, and won back many of the merchants who had abandoned the firm because of its high fees. He inspired fierce loyalty in his employees, boosting morale in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Chenault was designated to succeed the outgoing CEO in 1999 and officially took over the role in January 2001.

With 2003 sales of $25.9 billion American Express was a prominent financial-services firm and the world's number-one

travel agency. It issued traveler's checks, published magazines—such as Food & Wine and Travel & Leisure —and provided financial-advisory services. The company had four units: Global Corporate Services, Global Financial Services, Global Establishment Services and Traveler's Cheques, and U.S. Consumer and Small Business Services. On the Internet AMEX offered online banking and mortgage and brokerage services. Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway owned about 11 percent of the company. Key competitors included Carlson Wagonlit, JTB, and Visa.

BRAINS BUT LITTLE AMBITION AS A YOUNG MAN

Chenault's immense success in corporate America could not have been predicted based on his performance early in life. As a high-school student in a middle-class white community he received a slew of Cs—except in history class, where he typically earned As. His parents knew that he was extremely intelligent but worried about whether he had the focus to maximize his potential. They were certainly good role models: Chenault's father graduated first in his class at Howard University's Dental School, and his mother graduated at the top of her class at Howard's School of Dental Hygiene. While he had an incessant desire to learn, Chenault conceded in Ebony magazine with respect to his poor performance in school, "I'm sure it was frustrating for them that I was not applying myself" (July 1997).

Chenault eventually received crucial mentoring from Peter Curran, the head of Waldorf High School—a private school in Garden City, New York—who encouraged the wayward student to apply himself. When Chenault graduated, he did so with numerous honors; he had been class president, an honor student, and the captain of the basketball, soccer, and track teams. He enrolled in Springfield College in Massachusetts, which had offered him a sports scholarship, but craved a more academic experience and thus ended up at Bowdoin College in Maine.

MOTIVATED TO MAKE A DIFFERENCE

At Bowdoin, Chenault realized that he wanted to pursue a profession that would enable him to help other African Americans. He debated the merits of a corporate career with fellow African American students—there were 23 at Bowdoin at the time, as compared with the 950 white students—who warned of a lifestyle that might ultimately force him to abandon his convictions. Chenault disagreed, believing it to be possible for an African American to succeed without selling out. During these often-heated discussions, Chenault displayed his aptitude for debate. Rasuli Lewis, a fellow Bowdoin student who remained a friend, told Ebony , "His style was to come in more the middle of the road, to say let's consider both sides here, and to look at it from the point of fact rather than emotion" (July 1997).

Chenault had the ability to elicit respect from African American and white students alike. Geoffrey Canada, another college friend, told Fortune , "This was a time when people wanted you to choose sides; he sat with whomever he wanted. What was remarkable was that he could do that and still remain in the mainstream of both worlds. Other people would end up being shunned by one group or the other" (January 22, 2001).

LANDING A COVETED JOB WITHOUT AN MBA

After graduating from Bowdoin and later from Harvard Law School, Chenault spent two years in corporate law at Rogers & Wells and two more years at Bain & Company as a management consultant. W. Mitt Romney, the son of former governor of Michigan who had attended Harvard Law School with Chenault and gone on to Bain, recruited Chenault to the firm. Romney told Ebony , "I'll take full credit for hiring Ken. Although Ken lacked an MBA, he was a natural fit for the business world. He was able to process a lot of conflict and frenzy and still be able to cut through the confusion and arrive at very powerful conclusions and recommendations and then see them through to their implementation" (July 1997).

BOOSTING AMEX'S BUSINESS AND HIS STOCK

Recruited by the legendary Lou Gerstner in 1981, Chenault moved to American Express to become a director of Strategic Planning in Travel Related Services. In early 1983 he joined the company's merchandise-services unit, which sold items such as luggage tags and clocks to cardholders through direct mailings and catalogs. Gerstner and other AMEX executives actually discouraged Chenault from joining the unit, which lacked the platform and visibility of other divisions.

Chenault saw the move from an entirely different perspective, however: if he could turn around the struggling division, he thought, people would notice. Instead of luggage tags and clocks Chenault invested in bigger-ticket items such as electronics and home furnishings. He formed partnerships with Panasonic and Sharp, which were eager to expand the distribution channels for their recently released video recorders. In just three years the division's sales skyrocketed from $100 million to $700 million. Tom Flood, who worked under Chenault from 1983 to 1986, remarked in Fortune , "The business grew so quickly, and he had made such a quick impact, that his stock really rose after that. It put him on the map" (January 22, 2001).

TURNING AROUND AMEX

By the early 1990s Chenault was overseeing most of the company's travel-related services. It was a challenging period; the economy was weakened by a recession, the company's card business was losing customers to Visa and MasterCard, and merchants began protesting the high fees that they were being forced to pay: AMEX charged a fee of 4 percent of every transaction, while Visa charged less than half that amount. Due to the excessive fees many merchants—including a group of Boston restaurants whose collective decision was tagged as the "Boston Fee Party" by local papers—eventually refused to accept the American Express card. Chenault commented in Black Enterprise , "The focus in the early 1990s was frankly one of survival; we were falling off a cliff. But you can't stand still and say the objective is to survive in the long term. You have to say that the objective is to win" (September 30, 1999).

As president of the domestic consumer-card division Chenault was instrumental in turning around the charge-card business. His many accomplishments included expanding the company's customer base beyond the affluent cardholders who paid off their balances each month; signing on an impressive number of gas stations, discounters, and supermarkets as acceptors of the card; establishing the later highly regarded Membership Rewards loyalty program (one of the biggest—if not the biggest—rewards program on the market); and striking partnerships with companies like Delta Airlines, wherein the company expanded its lending business through the issuing of cobranded cards that allowed customers to carry balances.

Additionally Chenault reached a truce with merchants, though not everyone at AMEX agreed with his strategy—particularly his expansion into lower-end businesses like gas stations. Tom Ryder, who rose through the ranks alongside Chenault, said in Fortune , "It was an extremely unpopular stance. Ken was the leader of a fairly small group that said unless we made some fundamental changes, we were going to eventually get killed" (January 22, 2001).

RISING THROUGH THE RANKS BASED ON PERFORMANCE

Chenault eventually won dissenters over, gradually transforming AMEX from an uncompetitive, obsolete company into a booming business. The level of interest in the Membership Rewards program surprised even Chenault. Quests for airline miles generated a surge in AMEX charges, and the program helped AMEX woo new merchants as well: the number accepting the card grew from 3.6 million in 1993 to more than 7.2 million worldwide in 1999.

As AMEX's financial performance vaulted forward, so did Chenault's career. In 1993 AMEX's new CEO, Harvey Golub, appointed Chenault as head of U.S. Travel Services, a title that entailed responsibility for the company's entire domestic card business and about half of its revenues. Together Golub and Chenault restructured the company, generating more than $3 billion in savings, and continued an aggressive foray into mainstream businesses. In 1995 AMEX signed on with Wal-Mart—an important win in the fight with Visa and MasterCard for market share.

Between 1995 and 2000 earnings increased every year, reaching $2.8 billion in 2000. The number of American Express cards issued to consumers increased from 25.3 million in 1994 to more than 29 million by 1996. In 1995 Chenault was named vice chairman, and two years later he was named president and chief operating officer. In April 1999 he was named the eventual successor to Golub.

THE SOFTER SIDE OF A LEADER

The public undeniably wanted Chenault to succeed. Anne Busquet, the president of American Express Relationship Services, noted in Ebony , "You would go in elevators and hear, 'Isn't it exciting about Ken? Can you believe that Ken got promoted? Isn't it fantastic? Oh, I feel much better about the company now that Ken is president.' People wrote him notes; he was flooded with e-mail; there were flowers and calls from corporate and political leaders" (July 1997).

People inside the company looked up to Chenault—even those who had competed with him for the CEO spot. The intense loyalty that he generated in colleagues was a product of his low-key, caring management style. Rather than being afraid of their leader—as was the relationship between many subordinates and their CEOs—Chenault's employees enjoyed his inspiring presence. The classic axiom states that leaders can lead by fear or by love; Chenault seemed to motivate workers to fear losing his love. Louise Parent, the executive vice president and general counsel for the company, remarked in Black Enterprise , "He is the kind of person who inspires you to want to do your best. Part of the reason is his example" (September 30, 1999).

AN AFRICAN AMERICAN PIONEER

When in January 2001 Chenault claimed the top position at American Express—one of the best-known symbols of U.S. capitalism, then with yearly sales of $25 billion—the prospects for African Americans in corporate America had seemed dismal. At General Electric, for example, just one of the top 20 business units was led by an African American. Only two other African Americans headed Fortune 500 companies: Franklin Raines was the CEO of Fannie Mae, and A. Barry Rand was the CEO of Avis. John O. Utendahl, himself a high-ranking African American working in financial services and a close friend of Chenault, told Fortune , "When Ken joined American Express 20 years ago, no one would have taken the odds that he would be CEO. But as crazy as this may sound, Ken would have taken that bet. The playing field for minorities may not be level, but when Ken plays, he plays to win" (January 22, 2001).

For his part Chenault did not dwell on racial issues. He understood the social significance of his appointment but wanted people to judge him based solely on his performance. He commented in Fortune , "It's a big deal; I won't minimize it. But I want them to say, 'He's a terrific CEO,' not 'He's a terrific black CEO.' Because the reasons why I'm CEO have nothing to do with the social significance of this breakthrough. I've always been focused on performance" (January 22, 2001).

A CEO STUMBLES

Early in his tenure as CEO Chenault sent the message to Wall Street that he had not been completely prepared for the job. After announcing record earnings for 2000, several months later he shocked investors with news of a $182 million write-off on some surprisingly risky assets in the company's money-management division, American Express Financial Advisors. Chenault consequently reduced the company's junk portfolio from 12 percent to about 8 percent and decreased the risks of other investments.

Several months later Chenault caused an even bigger tremor when he announced an additional $826 million charge on the same portfolio; second-quarter earnings sagged 76 percent to $178 million. The central problem was an investment strategy in high-risk junk bonds that had been embarked upon years before Chenault would have his say. While no one could criticize Chenault for operations that had been initiated prior to his watch, critics were troubled by the fact that Chenault appeared to make no effort to understand what the company's rationale at the time had been. When asked in BusinessWeek why American Express would put its money into such a risky investment, Chenault responded by simply saying, "I don't know. This is a strategy that was embarked upon seven or eight years ago. I don't know all the rationale and philosophy" (October 29, 2001).

BOOSTING MORALE AFTER SEPTEMBER 11

Chenault showed his true colors as CEO in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on New York City. On the day of the attacks Chenault was stuck in Salt Lake City on a business trip. Still, he was able to make his leadership felt from afar, as he happened to be on the phone with a New York employee when the first plane crashed. AMEX's headquarters were across the street from the former World Trade Center; he asked to be transferred to security and told them to immediately evacuate everyone from the building.

In the hours and days that followed, Chenault made countless decisions that would ease the impact of the attacks on both cardholders and employees. To help the former, millions of dollars in late fees were forgiven, and credit limits were increased. In an effort to comfort the latter, Chenault invited his five thousand employees to New York's Paramount Theater on September 20 for a somber meeting. At that meeting he admitted that his grief had been so strong that he had needed to see a counselor. He announced plans to donate $1 million of the company's profits to the families of AMEX employees who had died on September 11. Charlene Barshefsky, a partner at Wilmer Cutler & Pickering who viewed a video of the event, told BusinessWeek , "The manner in which he took command, the comfort and the direction he gave to what was obviously an audience in shock was of a caliber one rarely sees" (October 29, 2001).

After 9/11 American Express committed to keeping its headquarters downtown; it was one of the first major companies to pledge their imminent return to Lower Manhattan.

Chenault commented in New York Voice Inc./Harlem USA , "Our 152-year history is filled with defining moments—staying open during crises when others close, coming through for our customers all around the world, doing the right things even when it is difficult to do. When we look back on this day several years from now, I believe we will see it as another defining moment that marked the beginning of a new era of growth and opportunity for our company and our city" (May 22, 2002).

FIGHTING FOR MARKET SHARES ON ALL FRONTS

In the first half of the 2000s Chenault continued pumping new blood into the AMEX brand. He pushed hard for the development of the Blue card, a trendy, fashionable card with a microchip allowing cardholders to make secure transactions online. The card appealed to the much-coveted younger demographic.

Further increasing the company's market share, Chenault led AMEX's campaign to build links with banks, changing the company's traditional policy of only issuing cards directly to consumers. He sold banks on the notion that they could increase their profitability by signing on with AMEX, because the company still took higher fees from merchants and because AMEX customers generally charged more money to their cards. Chenault said in American Banker , "The leverage that we had as a competitive advantage was a higher merchant discount rate" (June 30, 2000).

Chenault's strategy led to legal disputes with the Visa and MasterCard banking associations, which prohibited their members from issuing AMEX cards. In September 2003 a federal appeals court upheld a lower court ruling requiring Visa USA and MasterCard International to abandon long-held rules prohibiting member banks from issuing cards by American Express and other rivals. Visa and MasterCard said that they would appeal the ruling, while Chenault announced plans to forge partnerships with even more banks by the middle of 2004.

In one of Chenault's proudest accomplishments, he signed Tiger Woods to an AMEX contract. Both Chenault and Woods were leading figures who happened to be African Americans but whose winning appeal was truly universal.

See also entry on American Express Company in International Directory of Company Histories .

sources for further information

Byrne, John A., and Heather Timmons, "Tough Times for a New CEO," BusinessWeek , October 29, 2001, p. 64.

Fickenscher, Lisa, "The President of Amex Depicts It as Victim: Judge Admits Documents about DOJ Talks," American Banker , June 30, 2000, p. 1.

New York Voice Inc./Harlem USA , May 22, 2002, p. 19.

Pierce, Ponchitta, "Kenneth Chenault: Blazing New Paths in Corporate America," Ebony , July 1997, p. 58.

Schwartz, Nelson D., "What's in the Card for Amex? New CEO Ken Chenault Has No Shortage of Plans for American Express," Fortune , January 22, 2001, p. 58.

Whigham-Desir, Marjorie, "Leadership Has Its Rewards: Ken Chenault's Low-Key Yet Competitive Style Has Pushed Him Up the Executive Ladder and to the CEO's Chair," Black Enterprise , September 30, 1999, p. 73.

—Tim Halpern

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: