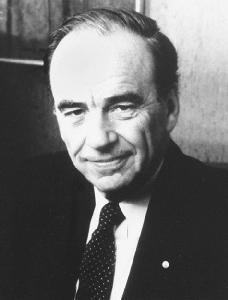

Rupert Murdoch

1931–

Chairman and chief executive officer, News Corporation

Nationality: American.

Born: March 11, 1931, in Melbourne, Australia.

Education: Worcester College, MA, 1953.

Family: Son of Keith Arthur Lay (journalist) and Elisabeth Joy Greene (philanthropist); married Patricia Brooker (airline stewardess; divorced); children: one; married Anna Torv (journalist and novelist; divorced); children: three; married Wendi Deng (secretary); children: two.

Career: Daily Express (London), 1953–1954, subeditor; Adelaide News , 1954–, publisher; Southern TV (Adelaide, Channel 9), 1959–, owner; Sydney Daily and Sunday Mirror , 1960–, publisher; Australian , 1964–, founder and publisher; London News of the World , 1969–, publisher; London Sun , 1969–, publisher; News International, 1969–1987, chairman of the board; 1969–1981, chief executive officer; News Corporation, 1979–, CEO; Times Newspapers Holdings, 1982–1990, chairman of the board; News Corporation, 1991–, chairman of the board; Twentieth Century Fox, 1992–, CEO and chairman of the board; Fox Inc., 1992–, CEO and chairman of the board; News International, 1994–1995, chairman of the board; Times Newspapers Holdings, 1994, chairman of the board; Fox Entertainment Group, 1995–, CEO; British Sky Broadcasting, 1999–, chairman of the board; Shine Ltd., 2001–, CEO and chairman of the board.

Awards: Humanitarian of the Year, United Jewish Appeal, 1997.

Address: News Corporation, 3rd Floor, 1211 Avenue of the Americas, New York, New York 10036-8701; http://www.newscorp.com.

■ Keith Rupert Murdoch was small, pudgy, short tempered, and blunt spoken; he was also charismatic, charming even to his enemies, and patient when criticized. A very complex man whom even his wives had trouble understanding, Murdoch created a media empire that was like his personality—contradictory, large, and dominating. He liked to describe

himself as colorless and boring, but numerous accounts by those who worked with him attested to his having been a stirring leader who could galvanize his employees to achievements that had seemed impossible.

THE EDUCATION OF RUPERT MURDOCH

Murdoch's father was Sir Keith Murdoch, who had been knighted for services to the crown and was a national hero in Australia. He was also one of the 20th century's most celebrated journalists: he was credited with revealing the truth about Britain's invasion of Gallipoli during World War I and with changing the British government's policy as a result, with troops being withdrawn from Turkey. Murdoch grew up in a spacious home near Melbourne and spent much of his time on a sheep ranch owned by his family.

The elder Murdoch was already severely ill with heart trouble when he sent his son to college in Oxford, England. The younger Murdoch developed an unsavory reputation for partying rather than studying, but his father's friend Lord Beaver-brook, publisher of the Daily Express (London), gave him work at the newspaper, where he quickly picked up Beaverbrook's flair for sensational headlines and snappy, short-sentenced prose. At the time Murdoch was a socialist who celebrated Lenin as a great man, and he proved to be such an adept debater in favor of his views that in 1950 he was elected president of Oxford's Labour Club.

Meanwhile, as the elder Murdoch remained seriously ill, a few of his subordinates conspired to relieve him of his ownership of the Melbourne Herald and other newspapers. After his father's death in 1952 the young Murdoch found that Australia's enormous death taxes had taken away most of the rest of his father's holdings. When he returned to Australia in 1954 Murdoch immediately began striving to build the circulation of a small Adelaide newspaper. Other publishers regarded him as a lazy, foolish young man and treated him with contempt—even into the 2000s Murdoch was chronically underestimated by his opposition. Yet he devoted himself to the publishing business with a passion and learned the details of every aspect of newspaper production. With sensational news stories and a punchy prose style, Murdoch's small holdings made money; he took risks by buying small newspapers that were losing money and then turning them around.

FOUNDATIONS OF EMPIRE

In July 1959 Murdoch bought his first television station, Channel 9 in Adelaide, calling it Southern TV. Throughout his life he would be on the lookout for new communications technologies, constantly trying to integrate them into his existing businesses. In 1960 he bought the Daily Mirror (Sydney) and its accompanying Sunday edition for $4 million; the publications quickly became notorious for bizarre and sensational headlines and stories about sex and mayhem. Perhaps in an effort to change his image as a purveyor of prurience, Murdoch established the Australian , a national newspaper that began publication in the capital of Canberra on July 14, 1964. The Australian was a serious publication featuring in-depth discussion of social issues and government policy and won the admiration of journalists.

In April 1967 Murdoch married for the second time, to Anna Torv, a reporter for the Daily Mirror . She would be his counterweight for over 30 years, pulling him back to his family when his work threatened to consume him. By 1968 Murdoch's Australian holdings were worth $50 million. He harbored resentment of the English upper class from his days in Oxford; they had made him feel like an outsider, as if they regarded Australians as inferior beings, and he wanted to strike back at them. In late 1968 he learned that London's Sunday publication News of the World was available. After a battle with other potential buyers, in January 1969 he bought 40 percent of the newspaper's shares, soon increasing the amount to 49 percent and instating himself as the newspaper's chief executive officer. In June 1969 he was elected chairman of the board for the newspaper.

In October 1969 he purchased the Sun (London), which had a circulation of 600,000 but was losing $5 million per year. When he announced that he would turn the Sun from a broadsheet to a tabloid, some of the newspaper's printers said the switch could not be made because the newspaper's printing machine could not be adjusted; Murdoch climbed on top of one of the huge machines, opened a cabinet, and pulled out a bar that when placed properly would convert the machine to a printer of tabloids. This was an important lesson for observers of Murdoch: he knew everything about running his businesses, down to the nitty-gritty of everyday production. On November 17, 1969, the first tabloid version of the Sun was published. On November 17, 1970, the first photograph of a half-naked woman was published; she and others would become known as Page 3 Girls. The Sun 's circulation rose to four million, and for the first of seemingly innumerable times, England's Press Council censured Murdoch for appealing to low-class readers—which were the very readers Murdoch wanted to appeal to. Further, the Sun tweaked the upper classes with tales of their infidelities, crimes, and foolishness.

In December 1969 Murdoch and his family were tending to business in Australia, leaving the use of their Rolls Royce in England to an editor's family. Alick McKay, the wife of the editor, took the automobile on a shopping trip and was kidnapped and murdered by men who thought she was Anna Murdoch. From that time onward Murdoch downplayed his dynamic personality and tried to keep himself and his family out of the news, not wanting outsiders to know their whereabouts.

INTO AMERICA

Murdoch wanted to expand his holdings into the United States; he chose to begin with two small, struggling newspapers, buying the San Antonio Express , the San Antonio News , and their united Sunday paper for $18 million in 1973. He revamped the News with his sex and mayhem formula while leaving the Express relatively untouched. He then established a national American newspaper, the National Star (later just the Star ), a tabloid that competed with the National Enquirer in the field of sensational, bizarre, and scarcely credible stories. Murdoch's formula came to include large photographs, big headlines, and brief stories. In 1974 Murdoch began spending most of his time in the United States; his wife had detested the snobbery in England and was happy to split her time between a 12-room duplex in New York City and a country farmhouse in rural New York.

On November 19, 1976, Murdoch bought the New York Post from Dorothy Schiff for about $50 million. He edited the Post personally for awhile, then hired the Time magazine editor Edwin Bolwell to do the job. The Post became a tabloid that revealed Murdoch's changing political sentiments. Previously known as Red Murdoch, he was shifting his views away from socialism; the Post began attacking liberal politicians who opposed Murdoch's expansion into the United States, especially the Massachusetts Senator Edward Kennedy, whose infidelities were covered in detail. On January 7, 1977, Murdoch bought the New York Magazine Company, publisher of New York, Village Voice , and New West , in a hostile takeover. New York would thrive; Village Voice would return to its gritty antiestablishment roots after years as a tepid social-life paper; and New West would fold after losing money, although it was regarded as a great magazine, comparable to New York .

In 1978 newspaper unions went on strike at New York's Times, Daily News , and Post production offices. Murdoch told the unions that if they returned to publishing the Post , he would later accept whatever terms they reached with the other two newspapers; thus the Post returned to full publication months before its rivals did. Meanwhile, Murdoch's newspapers in London were making large profits, and in February 1981 he used these profits to purchase the Times (London), creating a stir because of his existing possession of the lowbrow Sun and his status as a foreigner—he was seen as unfit to own the venerable English publication. In November 1983 he bought the Chicago Sun-Times for $90 million, creating similar worries in Chicago because the Sun-Times was considered a highbrow newspaper. Murdoch worked his usual magic, sensationalizing the Sun-Times and thereby expanding its circulation. "I don't run anything for respectability," Murdoch was quoted as saying in William Shawcross's biography, Murdoch (1992). By 1984 Murdoch's holding company News Corporation owned 80 newspapers and magazines.

FOX

In early 1985 Murdoch bought half of Fox for $250 million, and on May 6, 1985, Twentieth Century Fox bought Metromedia's seven television stations for $2 billion. By then Murdoch's assets were worth $4.7 billion, with annual revenues of $2.6 billion—but he was borrowing heavily to expand into the American television market. In the United States, only an American citizen could hold a majority interest in a television station, which meant the Metromedia stations could not be owned by Murdoch; Australia had a similar rule. Murdoch obtained an exception in Australia, and on September 4, 1985, he became a U.S. citizen. The rest of his family remained Australian citizens.

In 1985 Murdoch instituted sweeping production changes in all of his London newspapers. He wanted to change from double keystroking (wherein an editor creates a page, and then a printer resets it) to single keystroking (wherein a computer is used, and the typesetting is done entirely by the editor), which would cut labor costs. British labor unions had long enjoyed special privileges at London newspapers. For instance, whenever a newspaper introduced new technology, the union printers would be paid as if there were more printers than there actually were; at the Times , it was possible for 10 workers to be paid the wages of 17. In secret, Murdoch built huge printing plants in Wapping and Glasgow, and on January 25, 1986, he began printing all his London newspapers in these plants. A long, violent strike ensued, featuring a pair of riots in Wapping. Murdoch offered a series of compromises that were rejected; the union workers eventually lost their jobs and most of their benefits, with the strike ending in January 1987. By then Murdoch owned about 30 percent of British newspapers. That same month Murdoch bought his father's old newspaper, the Melbourne Herald . On March 1, 1987, Murdoch launched the Fox television network. American rules forbade a motion picture studio from owning a television network, so the Fox network at first ran only 14 hours of national programming—one hour less than the legal definition for a network. It took persistent and skillful politicking by Murdoch to have the rules changed so that Fox could expand its programming.

TROUBLED TIMES

In 1988 Senator Kennedy exacted revenge against Murdoch by slipping a small amendment into an appropriations bill that forced Murdoch to sell the Post because he also owned a television station in New York. Companies were not supposed to own a television station and a newspaper in the same city, but the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) had granted Murdoch an exemption; Kennedy's amendment ended that exemption. In England, Murdoch had tried to launch a satellite-television service in 1983 but had failed, losing $20 million. In February 1989 he started Sky Television, a satellite service with four channels. He initially lost money on the venture as a result of providing satellite boxes for free; the investment would later pay off when he was able to offer over four hundred channels to subscribers.

In 1990 Murdoch's News Corporation was worth $19 billion, but it was $8.1 billion in debt, and most of the debt was due. Murdoch had to restructure his debts, in part by issuing new stock that diluted the percentage of shares he owned, weakening his control over the businesses. Exercising his persuasive powers to their fullest, he convinced American banks to give him extensions to 1993 to pay what he owed them. Without these extensions he might have lost News Corporation altogether.

In 1991 the Murdoch family moved to Los Angeles. Anna had felt like an outsider in New York; in the Los Angeles home she was the happiest that she had been since leaving Australia. Fueled by profits from his London holdings, Murdoch quickly bought back control of his businesses. In February 1992 his personal wealth was estimated at $2.7 billion. In 1993 he took one of the most breathtaking risks of his career, buying Asia's Star Television, a satellite service that covered southern Asia from the Middle East to Japan. With the laws of many different countries involved, Murdoch would spend much of the next decade negotiating deals with various governments. By 2000 Star Television would have over 300 million subscribers. Also in 1993 the New York Post went bankrupt; the FCC granted Murdoch a special exemption to save the newspaper, arguing that either Murdoch would be allowed to own the newspaper or it would die. Thus, he regained what Kennedy had taken from him.

MORE RISKS, MORE GROWTH

In 1994 Murdoch dropped the BBC from Star Television amid protests that he was bowing to complaints from China's dictators, who said the BBC portrayed them badly. Murdoch's response was that he personally disliked the BBC, which was true; he regarded the BBC as an elitist organization that helped prevent the United Kingdom's society from becoming fully free and democratic. The accusation that he was unethically catering to China's dictators would return with more justification when in 1998 his book-publishing firm HarperCollins broke its agreement to publish the memoirs of the last governor of Hong Kong, Chris Patten, supposedly because Patten was overly critical of Chinese communists.

In 1994 Fox bought the rights to broadcast National Football League games for $1.58 billion over five years, meaning that the network would lose $100 million per year. Murdoch averred, however, that his local stations would make up the $100 million in advertising revenues. In 1997 he bought Major League Baseball's Los Angeles Dodgers for $350 million, the International Family Entertainment religious cable network for $1.9 billion, Heritage Media for $1.41 billion, and 40 percent of Rainbow Media Sports Holdings for $850 million. The last of these deals gave Murdoch part ownership of the National Basketball Association's New York Knicks and the National Hockey League's New York Rangers. Murdoch planned to use his sports holdings for overseas broadcasts, noting that the Dodgers in particular had a globally recognizable brand name. On September 21, 1998, Murdoch's British Sky Broadcasting bought British soccer's Manchester United, the most popular sports team on the planet, for $1.5 billion.

In June 1999 Murdoch divorced Anna, worrying many colleagues who saw her as an essential, stabilizing influence on his life. Only three weeks later, in an unpublicized ceremony, he married Wendi Deng, a Chinese employee of Star Television. Those in attendance did not know they were attending anything other than a party on Murdoch's boat until the ceremony began.

In 2000 News Corporation was worth $38 billion, with annual sales of $14 billion. It bought Chris-Craft's 10 television stations for $5.3 billion in stock. By 2002 Murdoch owned more than 750 businesses in more than 50 countries. In December 2003 Murdoch made one of his most daring purchases when his News Corporation paid $6.8 billion for the controlling interest in DIRECTV, an American satellite-television service. This purchase would enable Murdoch to broaden the reach of his existing television services as well as to profit from the dissemination of other television services that would be required to pay him to carry their shows. For 2003 News Corporation netted $1.1 billion and grossed $17.5 billion.

News Corporation was first incorporated in Australia; in 2004 Murdoch reincorporated his company, shifting it from Australia to the United States. By that year Murdoch's 35 American television stations reached 40 percent of America's population. Murdoch himself had come to be regarded by many as an extreme right-wing ideologue; he seemed to have changed his thinking about socialism, which he saw as a poison embodied in government regulatory agencies. He never escaped from bitter criticism that he published vulgar newspapers that demeaned society by emphasizing sex and mayhem at the expense of reasoned discussion. It was Murdoch's view that he was an entertainer, not an informer, and that he merely sold entertainment to his readers, most of whom were lower-class workers and middle-class women. He was unapologetic about his influence on public discourse. Amid complaints that Fox slanted the news in favor of government policies that he advocated, he insisted that he saw no such slant. To his credit, his response to criticism was exclusively verbal; he did not sue or otherwise try to silence his critics, even when they accused him of being a liar or a criminal. He allowed them the same freedom to express their opinions that he wanted for his own publications.

Although regarded as an evil genius by some, Murdoch did not seem to have regarded himself as any sort of genius, but rather as a hardworking taker of risks. In that respect he was extraordinary, continually bouncing back from failures to find new ventures to conquer. He loved to build businesses, and he regularly worked 16-hours days into his 70s, asserting that he would never quit, noting that his mother was in her 90s. He seemed to take the greatest pleasure in turning around failed businesses, which he did without initially overanalyzing or worrying about profit and losses. Instead, he focused on seizing opportunities, confident in his ability to build and motivate goal-oriented teams and in his own extraordinary persuasive powers, with which he convinced employees and bankers of the vitality and potential for success of his enterprises.

See also entries on British Sky Broadcasting Group plc, Fox Entertainment Group, Inc., News Corporation Limited, and Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation in International Directory of Company Histories .

sources for further information

Fallows, James, "The Age of Murdoch," Atlantic Monthly , September 2003, pp. 81–96.

Grover, Ronald, and Tom Lowry, "Rupert's World: With DirecTV, Murdoch Finally Has a Global Satellite Empire; Get Ready for a Fierce Media War," BusinessWeek , January 19, 2004, pp. 52–59.

Shah, Diane K., "Will Rupert Buy L.A.?" Los Angeles Magazine , December 1997, pp. 108–114.

Shawcross, William, Murdoch , New York, N.Y.: Simon & Schuster, 1992.

—Kirk H. Beetz

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: