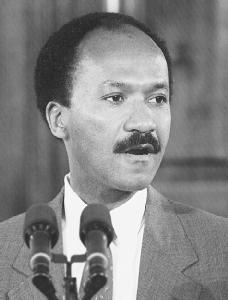

Franklin D. Raines

1949–

Chairman and chief executive officer, Fannie Mae

Nationality: American.

Born: January 14, 1949, in Seattle, Washington.

Education: Harvard College, BA, 1971; Oxford University, 1971–1973; Harvard Law School, JD, 1976.

Family: Son of Delno and Ida Raines (both custodians); married Wendy Farrow; children: three.

Career: Office of Senator Moynihan, 1969, intern; Seattle Model Cities Program, 1972–1973, associate director; Preston, Thorgrimson, Ellis, Holman & Fletcher, 1976–1977, attorney; White House Domestic Policy Staff, 1977–1978, assistant director; U.S. Office of Management and Budget, 1978–1979, associate director; Lazard Frères & Company, 1979–1982, vice president; 1983–1984, senior vice president; 1985–1991, partner; Fannie Mae, 1991–1996, vice chairman; U.S. Office of Management and Budget, 1996–1998, director; Fannie Mae, 1998, chairman; 1999–, chairman and chief executive officer.

Address: Fannie Mae, 3900 Wisconsin Avenue NW, Washington, D.C. 20016; http://www.fanniemae.com.

■ The first African American CEO of a Fortune 500 corporation, Franklin D. Raines was named chairman and CEO of Fannie Mae on January 1, 1999. Under his leadership, Fannie Mae—short for the Federal National Mortgage Association—remained a major player in what Raines called the "American Dream Business," ( Financial Times , October 29, 2002) continued its record of double-digit operating income growth, expanded its product and technology leadership, and committed to invest $2 trillion to finance affordable homeownership and rental housing for 18 million families.

In 2003, with revenues of $53.8 billion, Fannie Mae was the number one source for home mortgage financing in the United States, providing liquidity in the mortgage market by buying mortgages from lenders and packaging them for resale, transferring risk from lenders and allowing them to offer mortgages

to those who may not otherwise qualify. Fannie Mae was one of several government-sponsored enterprises, which were stockholder-owned companies created by Congress to carry out a public-policy purpose with private capital. Fannie Mae bought home loans from banks and other mortgage lenders, providing those lenders with a fresh supply of cash to make new loans. Fannie Mae also invested in mortgage-backed securities. It benefited from low interest rates, tax exemptions, and an implicit guarantee of federal support.

OVERACHIEVER FROM AGE EIGHT

Named after the famed president Franklin D. Roosevelt, Raines, one of seven children, was born in Seattle, Washington. His parents, Delno and Ida Raines, both worked as custodians (neither finished high school). After paying the state $1,000 for a house that was to be torn down, Delno Raines dug a foundation and used the lumber from the ramshackle house to build a new one. Within five years he had put in the drywall and plumbing. When Delno Raines was hospitalized, the younger Raines began working at the age of eight, helping his mother support the family. Raines's parents never earned more than $15,000 a year, yet his father managed to leave behind $300,000 when he died. Raines remarked, "It's a dramatic demonstration of how important access to capital and homeownership are in the lives of working-class people" ( BusinessWeek , December 9, 2002).

In high school Raines was the classic overachiever. His honors included captain of the football team, statewide debating champ, and student body president. Continuing on that track, he earned a scholarship to Harvard, where he graduated magna cum laude with a BA degree in government. Raines gravitated toward contentious situations, organizing a campuswide strike at Harvard to protest police actions. He became a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University and earned a law degree from Harvard Law School. His foray into politics was marked by an internship with Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan's office.

FROM THE WHITE HOUSE TO THE HOUSING MARKET

After college Raines fulfilled his political ambitions, working for President Richard Nixon and then President Jimmy Carter in various economic posts. Throughout the 1980s he was employed with Lazard, Frères & Company, the investment banking firm, where he worked in municipal finance and was named a general partner. In 1991 Fannie Mae recruited Raines, offering him the title of vice chairman.

One of Raines's early contributions to Fannie Mae was promoting the use of technology as a tool for reducing risk and fueling growth, investing massive amounts of money to bring the company up to date with sophisticated automating systems and Internet applications. Two results of that initiative were the "Desk Top Underwriter," an automated underwriting system that allowed lenders to originate mortgages in a cheaper and more efficient manner, and "Desk Top Home Counselor," an electronic system that helped loan counselors repair the credit of prospective buyers so that they could quality for mortgages.

The importance of technology was made apparent to Raines on one of his first days on the job. He needed to cash a check, yet he could not find a place anywhere in the building that could give him money. Said Raines, "What that said to me was: All of the company's billions of dollars are in the computers down in the basement. From there it struck me that our major competitive tool was technology and matching technology to mortgages. It wasn't going to be marketing or hands-on service, because of the kind of product we have—a high-value product with enormous processing costs" ( American Banker , January 31, 2001.)

LEARNING HOW TO NEGOTIATE

In 1996 the White House came calling again. President Clinton tapped Raines as a member of his cabinet and as director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Raines was the president's key negotiator in the talks that led to passage of the bipartisan Balanced Budget Act of 1997. Raines was the first OMB director in a generation to have balanced the federal budget. Raines noted, "When you're the OMB director, every day you're dealing with people who want things and conflicts that have to be resolved…. Both sides of the aisle found they could trust me" ( American Banker , January 31, 2001.)

AN AFRICAN AMERICAN ROLE MODEL

In the spring of 1998 Raines announced that he was leaving his position at the White House to become chairman and CEO of Fannie Mae. His appointment marked the first time in history that an African American executive had taken the top position at a Fortune 500 company. Hugh Price, president of the National Urban League, said, "I consider Frank Raines the Jackie Robinson of corporate America" ( Black Enterprise , August 31, 1998). Not only was Raines setting an important example for fellow African American executives, but he was also doing so at a firm that would be immensely helpful to African American home buyers. One of his goals was to increase the population of African American and Hispanic homeowners.

Raines's position came with a $7 million annual compensation package and instant credibility in corporate circles. Said Raines, "The boards of companies tend to be fairly conservative, and the fact that the Fannie Mae board saw me as the best CEO, I think, will be reassuring to other boards as they seek to promote black executives" ( Black Enterprise , August 31, 1998).

UNDER ATTACK

Raines became chairman and CEO of Fannie Mae on January 1, 1999. Immediately he had to contend with an unprecedented attack by both industry rivals and government officials. Critics in Congress were pressing for a single influential regulator to replace the two weak agencies that had long monitored government-sponsored entities. Meanwhile, big banks and mortgage insurance companies created a Washington lobbying group called FMWatch to monitor the activities of Fannie Mae and its smaller rival, Freddie Mac.

One of the group's primary concerns was the company's foray—what the group derisively called "mission creep"—into home equity financing and subprime mortgage lending. In response to his critics, Raines showed no intention of slowing down. Raines remarked, "There is a school of thought that if you harass Fannie Mae, maybe they'll pull their punches, maybe they'll slow down, maybe they'll not be as good a company. But anybody who knows me knows that would be a very large tactical error. Anyone who thinks that trying to intimidate us would be productive would be making a mistake" ( American Banker , January 31, 2001).

POST-ENRON SCRUTINY

In 2002, with investors facing as much as $25 billion in shareholder losses from the Enron debacle, government officials began paying even closer attention to corporate governance. Fannie Mae became a target of this scrutiny. To understand why is to understand Fannie's complex history. President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the company in 1938 as way to free up money in the housing market. In 1968 Congress deemed Fannie Mae a government-sponsored private enterprise, which meant a presumed federal guarantee of the company's debt. In fact, Fannie had a $2.25 billion line of credit with the U.S. Treasury. That benefit enabled the company to obtain a lower-than-average rate on the debt it issued. Banks gave the company loans at rates nearly as low as those paid by the government on its own debt. As a result, the company profited on the difference between the rate of the mortgages it bought and the rate of the money it borrowed.

The Congressional Budget Office said that the company's entitlements as a government-sponsored entity amounted to $6.1 billion in 2000; Fannie put that number at $3 billion to $3.6 billion. The true number most likely lay somewhere in the middle, but the result of the fiscal benefit was undeniable: at least 16 years of double-digit profit growth. Critics warned that during these years of explosive growth, the company had taken on a dangerous level of risk. Industry insiders had long questioned the operations of both Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, in essence stating that the firms' highly complex financial transactions were created as a shield to hide the volatility of their businesses. For decades stock investors favored Fannie and Freddie for their smooth, predictable earnings growth. That predictability went out the window in 2001, thanks to new accounting rules for derivatives—complex financial contracts that Fannie and Freddie used to protect their earnings against swings in interest rates. The derivatives themselves could have wide swings in value.

A RIVAL'S SCANDAL TURNS UP THE HEAT

In June 2003 Fannie Mae's primary rival, Freddie Mac, fired its chairman and CEO, CFO, and COO following an accounting scandal. The company became the subject of a formal investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regarding whether Freddie Mac was manipulating its earnings or, worse, attempting to disguise the amount of its credit or other risk.

The Freddie Mac scandal had severe repercussions for Fannie Mae. It generated uncertainty in the capital markets, which led to higher interest rates and an inability on the part of Fannie to do more for its consumers. Raines remarked, "I jokingly said to friends that I now know what the definition of collateral damage is" ( Fair Disclosure Wire , July 30, 2003). When asked in a press conference if Fannie Mae had used any accounting judgment that either its employees or its auditors considered debatable, Raines responded, "The answer to that is clearly, no. We have not. If we had, I would have violated the law in certifying our financial results. If we had, our auditors would be obligated to publicly do something about that. So I do not think that there is any question on that, of our taking any steps to subvert accounting" ( Fair Disclosure Wire , July 30, 2003).

Raines responded to the calls for increased scrutiny with the adeptness of a politician campaigning for reelection. He supported plans for stronger regulation of Fannie Mae and other government-sponsored entities while warning of the repercussions of reining in the company's charter. Said Raines in a 2003 speech at George Washington University, "In pursuing positive reform, we believe—and I think most policymakers believe—that Congress needs to be extraordinarily careful to avoid changes that would undermine our mission and stifle the flow of low-cost mortgage capital and mortgage innovations" ( CBS MarketWatch.com , December 17, 2003).

A SAVVY POLITICAL OPERATIVE

Raines had long used his impressive political connections to defend attacks on Fannie Mae. When Representative Christopher Shays (R-Connecticut) presented legislation to force Fannie Mae to begin registering with the SEC, he came face-to-face with Raines's political power.

Immediately each member of the U.S. House of Representatives was mailed a letter saying that more than two dozen groups, including the National Association of Realtors and the National Council of La Raza, which represented Hispanic Americans, would fight the bill based on the negative effects it would have on consumers. Shays recalled, "I felt like I kicked a hornet's nest" ( BusinessWeek , December 9, 2002). Fannie Mae ultimately relented and became an SEC registrant.

The extent of confidence in Raines was illustrated in the tepid reaction from government officials in response to Fannie Mae's October 2003 announcement that it had to correct quarterly financial results. An incorrect application of accounting standards led to an adjustment of some figures by more than $1 billion. The day after the announcement, Paul S. Sarbanes of Maryland, a top Democrat on the Senate Banking Committee, brushed off the news as a nonevent. Said Sarbanes, "It didn't affect their financial strength. That's an important consideration" ( Congressional Quarterly Weekly , April 16, 2004). But others saw such a reaction as further evidence of a problem. Said Representative Richard H. Baker (R-Louisiana), a longtime Raines nemesis, "If this were any other publicly traded corporation of any stature, those statements would be of such enormous consequences in the market that you might have to suspend trading. It has not yet had that kind of effect…. So there isn't any market discipline here, and that's what makes them unique" ( Congressional Quarterly Weekly , April 16, 2004).

UNCLEAR FUTURE

In 2004 the Bush administration, some members of Con gress, and several competitors in the housing market continued to raise questions about whether Fannie Mae's size and growth posed a risk to the nation's economy and whether the company and its smaller rival, Freddie Mac, required more oversight.

That year Senator Richard C. Shelby (R-Alabama), chairman of the Banking Committee, introduced a bill proposing a new regulator with significant power to police both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. In a particularly controversial aspect of the bill, the new regulator had the power to appoint a receiver to sell assets and pay off creditors in the event that either company faced a financial disaster. The provision challenged the long-standing belief that the government would bail out the company in the case of such an event. In April 2004 the Banking Committee approved the bill, but its long-term prospects seemed dubious. Said Shelby, "I don't see the bill moving. We're up against a powerful lobby" ( Congressional Quarterly Weekly , April 16, 2004).

Also in 2004 the Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight, an agency in the Department of Housing and Urban Development created in 1992 to regulate Fannie and Freddie, began an investigation into Fannie Mae's accounting to determine potential improprieties in earnings management. Said John Barnett, an analyst at the Center for Financial Research and Analysis in Rockville, Maryland, who had studied Fannie Mae's financial statements, "My main concern is that they're not as well capitalized as the minimum or risk-based capital standards would require them to be" ( Congressional Quarterly Weekly , April 16, 2004).

BACK TO THE WHITE HOUSE?

Company officials credited Raines with initiatives to make the company's financial transactions more transparent and said that the accounting scandal at Freddie had nothing to do with Raines. But the increased government scrutiny combined with Fannie Mae's lackluster stock performance—between 1998 and 2003 the stock remained flat—spelled potential trouble for Raines.

Raines could find an escape hatch in politics. Some expected he would return to his past as a government official. In a fall 2003 interview with one industry publication, Raines said his career in government service was over. But not everyone was convinced. Said one mortgage executive, who asked to remain anonymous, "Anyone who says that Frank is done with politics is misguided. He has made all the money he will ever need. He is a sincere public servant" ( National Mortgage News , May 3, 2004).

See also entry on Fannie Mae in International Directory of Company Histories .

sources for further information

Boland, Vincent, "Why Americans Feel at Home with Fannie Mae," Financial Times (London, England), October 29, 2002.

Cohn, Laura, "Protecting Fannie's Franchise," BusinessWeek , December 9, 2002, p. 94.

"A Conversation with Franklin D. Raines, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, Fannie Mae," Fair Disclosure Wire , July 30, 2003.

Harris, Hamil R., "Franklin Reigns: Franklin Raines Returns to Fannie Mae as the First Black CEO of a Fortune 500 Corporation," Black Enterprise , August 31, 1998, p. 103.

Hughes, Siobhan, "Fannie and Freddie: Too Big to Fail, Too Big to Regulate," Congressional Quarterly Weekly , April 16, 2004.

Muolo, Paul, "Analysis: Stock Price a Blemish," National Mortgage News , May 3, 2004, p. 1.

Rosenberg, Hilary, "Fannie Mae CEO Poised For Fresh Onslaught," American Banker , January 31, 2001, p. 1.

Watts, William L., "Raines Defends Fannie Mae's Charter," CBS MarketWatch.com , December 17, 2003.

—Tim Halpern

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: