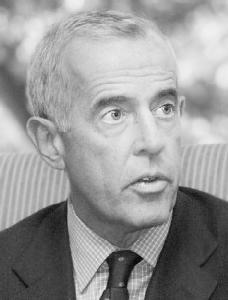

Robert Walter

1945–

Chairman and chief executive officer, Cardinal Health

Nationality: American.

Born: July 13, 1945, in Columbus, Ohio.

Education: Ohio State University, BS, 1967; Harvard University, MBA, 1970.

Family: Son of a food broker in Ohio; married Peggy McGreevey, 1967; children: three.

Career: North American Rockwell, 1968, engineer; Cardinal Foods, 1971–1980, CEO; Cardinal Distribution, 1980–1994, CEO; Cardinal Health, 1994–, CEO.

Awards: Honorary Doctorate, Ohio University, 1997; Christopher Columbus Award, Greater Columbus Chamber of Commerce, 2001.

Address: Cardinal Health, 7000 Cardinal Place, Dublin, Ohio 43017; http://www.cardinal.com.

■ Robert Walter founded the food-distribution business Cardinal Foods in 1971. In 1980 he began diversifying the company to pharmaceutical distribution and in 1987 sold off its food distribution component; in 1994 the company's name was changed to Cardinal Health. By the late 1990s, after acquiring numerous other companies under Walter's direction as CEO, Cardinal had become a large, highly profitable health-care conglomerate engaged in the manufacture and distribution of drugs and medical and surgical supplies. Walter remained the CEO of Cardinal through 2004. Analysts and friends described him as modest, highly competitive, and a superb deal-maker, and he repeatedly attributed his success with Cardinal to "sneaking up" on his competition and to carefully avoiding the pitfalls of big-company culture.

EDUCATION AND FORMATIVE EXPERIENCE WITH ROCKWELL

As an undergraduate at Ohio State University Robert Walter never missed a class. A classmate who eventually became

a CEO himself said that Walter showed a knack for dealing with complexity and prioritizing. Walter graduated summa cum laude in 1967 with a BS in mechanical engineering and went straight to work for the missile maker North American Rockwell (which later became Rockwell International). The experience was formative: Walter loathed Rockwell's corporate culture, where individual initiative was swallowed up in bu reaucracy. As Walter saw it, the company was overstaffed, hampered by a rigid seniority system, and made lazy by risk-free, cost-plus government contracts. He was later to describe his stint at Rockwell as the worst and scariest experience of his career. After only six months Walters left for Harvard Business School, determined never to work for an oversized company again.

FOUNDS CARDINAL AS A FOOD DISTRIBUTOR

Fresh out of Harvard's MBA program Walter decided to acquire and rehabilitate a mismanaged company in a simple line of business. He returned to Columbus, borrowed $1.3 million, and acquired the ailing food-distribution division of Consolidated Foods in a leveraged buyout in 1971; he christened his new company Cardinal Foods. Its business was indeed simple: to truck food from wholesale outlets to retail stores. Walter managed Cardinal into a major regional food distributor, increasing its sales tenfold by 1980. At that point, however, he ran out of headroom. The U.S. food-distribution business had been consolidated into the hands of a few large companies—too large for Cardinal to acquire or compete with for market share. As a food-distribution business Cardinal was poised to diversify into the realms of either food or distribution alone. Walter tried to diversify within the food business by starting a supermarket chain but failed, an experience that he later characterized as his most humbling.

DIVERSIFIES CARDINAL

Diversifying into food retailing had been unsuccessful, but Walter reasoned that he could still translate his understanding of food distribution into the distribution of other items. Researching the industry, he found that although food distribution had already been heavily consolidated, drug distribution was still highly fragmented. At that time there were 354 independent distributors in the United States and only three public companies. (Thanks in large part to Walter himself, drug distribution would eventually go the way of food distribution: by 2003 Cardinal and its two biggest competitors controlled 90 percent of the drug-distribution market.) In 1980 Walter purchased Baily Drug, the Ohio company that distributed drugs to pharmacies, and renamed his own company Cardinal Distribution to reflect its expanded scope. Three years later he purchased four midwestern drug-distribution centers and took his company public. In the next few years Cardinal swiftly expanded—always by acquisition, always under Walter's personal control, and always in the drug distribution business, which remained simple: Cardinal bought drugs from makers like Pfizer and trucked them to customers like hospitals or the pharmacy chain CVS.

In 1988 Walters sold off the food-distribution segment of Cardinal; for the next six years he concentrated on expanding Cardinal's drug distribution business beyond the Midwest. By 1994 Cardinal had been doing nothing but transporting drugs and acquiring smaller distributors for some 14 years. Concerned that Cardinal's narrowness made it vulnerable to market instability and declining profit margins in drug distribution, Walters decided to diversify. He changed the company's name to Cardinal Health and in 1995 made his first nondistribution acquisition, Medicine Shoppe International (a large franchiser of retail pharmacies). In the following years Cardinal continued to diversify, expanding into higher-margin businesses like drug manufacture and the distribution of nondrug medical, surgical, and laboratory products. In 1996 it purchased Pyxis, the maker of automated drug-dispensing machines used by nurses in hospitals. In 1999 Cardinal purchased Allegiance Corporation, the manufacturer and distributor of medical-surgical products, for $5.4 billion. By 2001 Cardinal had increased its earnings by more than 20 percent annually for 15 consecutive years. By 2004 it was the third-largest health-care service provider in the United States, worth approximately $44 billion and employing about 50,000 people (40 percent of whom worked abroad, mostly in manufacturing).

ACQUISITION AS A BUSINESS: HIGH STANDARDS, CALCULATED RISKS

Walter established Cardinal by acquisition and spurred its growth through acquisition. His skill was not in the creation of brand-new businesses or industries but in the gluing together of existing pieces. As Walter himself told the industry journal Modern Healthcare in 1999, "I don't think my expertise ever has been to start businesses up. What I want to focus on is finding good base businesses that I think I can improve" (April 19, 1999). Indeed, between 1983 and 2001 Walter oversaw more than one hundred acquisitions; in 1996 he went as far as to state that acquisition was a line of business at Cardinal.

Walter succeeded at the notoriously risky business of company-buying through a blend of ambition and conservatism. Friends and colleagues described him as intensely ambitious, both at work and at play—he was consistently ranked among the top five CEO golfers in the United States in the late 1990s and early 2000s—but he tempered his urge to get ahead with cautious deal-making. Once Cardinal had gained recognition as a national company, Walter instituted a policy of never acquiring businesses that were not ranked first or second in their market areas, shunning high-risk deals. He also took an approach to acquisition—first in food distribution and later in health care—that was plodding compared to those of other diversifiers. He only acquired companies that his existing customer base already depended on and trusted, thus continually increasing Cardinal's indispensability to those who relied upon it. Cardinal acquired one of every 50 companies it considered buying; Walters said in 2003 that the mark of successful risk takers was that they calculated the odds well.

In 2003 Euromoney Institutional Investor characterized Walter as "methodical in the way he seeks out higher-margin opportunities that complement the core business" (January 2003). Lawrence Marsh, the senior vice president at Lehman Brothers in New York, said in 1999 in Modern Healthcare that Walter and his team were "stellar in my book" because they took "calculated, prudent bets" (April 19, 1999). According to Walter, another guiding principle of his expansion strategy was to always acquire businesses with a higher profit margin than Cardinal already had. Yet in 2002, 56 percent of Cardinal's operating earnings still came from drug distribution, its least-profitable major asset, underlining the conservatism of Walter's acquisition philosophy.

Walter never forgot his youthful loathing of the corporate culture at North American Rockwell. Even when his own company had become undeniably large, Walter adamantly maintained a smaller-business feeling. He allowed executives from acquired companies to retain a large degree of autonomy; as a result Cardinal became a conglomeration of small segments, with the people in charge of each segment given a high degree of authority and responsibility and asked to act quickly and decisively, as if they were the owners.

BUMPS IN THE ROAD

Walter's upward course was not without setbacks. In 1998 the Federal Trade Commission brought a successful antitrust suit against Cardinal's attempt to acquire Bergen Brunswig Corporation, the competing health-supplies distributor. The following year Walter unhesitatingly turned to planning the purchase of another distributor, Allegiance—despite the fact that on the strength of the Internet bubble of the late 1990s some analysts were saying online ordering would eliminate distributors altogether. When the Internet bubble burst at the end of the 20th century, Walter's actions were deemed more reasonable.

In June 2002 Cardinal announced that it was buying Syncor International Corporation for $1.1 billion in a bid to expand its business in nuclear pharmaceuticals (radioactive materials used for diagnostic purposes in hospitals). Then the news broke that Syncor had made improper payments to state-owned health-care employees in Taiwan. After researching the matter, Walter and his team decided that the bribery had been small-scale and not connected with Syncor's main business; Walter gave the deal the go-ahead and the acquisition proved stable. Also in 2002 Walter was obligated to take a conference call with major investors to assure them that the fact that Arthur Andersen had been Cardinal's auditor did not mean that a Cardinal scandal was about to break. (Andersen had just been convicted of obstructing the federal Securities and Exchange Commission's investigation of its client bankrupt energy-giant Enron.)

In March 2004, in the wake of a string of disasters involving overreporting of income by large corporations, Bristol-Meyers announced that it had incorrectly recorded incentives paid to Cardinal to accept excess inventory. Once again Walter's caution paid off: he was able to prove to Cardinal's investors that the company had only recorded revenues for merchandise actually sold to retailers and that there would be no need for restatements of income.

Throughout this string of near disasters, Walter's attachment to basic business—comprising tangible goods and services, low debt, and straightforward accounting—stood Cardinal, its investors, and its employees (who owned 10 percent of the company) in good stead. As of 2004 Cardinal was the world's largest provider of health-care products and services. Its success reflected to an unusual degree the cautious deal-making practices of its lifetime CEO Robert Walter. "He's one of the best managers I've ever seen," said Peter Lynch, the vice chairman of the investment-advisor arm of Fidelity Investments, in Fortune , "and I've seen thousands" (April 14, 2003).

See also entry on Cardinal Health, Inc. in International Directory of Company Histories .

sources for further information

"America's Best CEOs," Euromoney Institutional Investor , January 2003.

Borden, William, "Interview: Cardinal CEO Quietly Builds a Giant," Reuters, August 19, 2002.

Carter, Ron, "Shopping Spree: Cardinal Health Ringing Up Purchase after Purchase," Business Today , August 5, 1996.

Casey, Mary Alice, "Hard Work, High Standards: Fortune 100 CEO Remains Committed to His University," Ohio Today , Spring 2001.

Hensley, Scott, "The Cardinal Rules: Growth, Agility," Modern Healthcare , April 19, 1999.

Lashinsky, Adam, "Big Man in the Middle," Fortune , April 14, 2003.

Williams, Mark, "Cardinal CEO Quietly Builds Powerful Company," Associated Press, February 26, 2003.

—Larry Gilman

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: