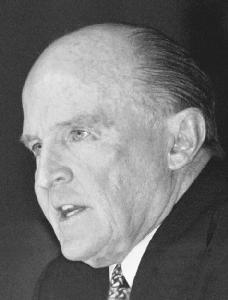

Jack Welch

1935–

Former chairman and chief executive officer, General Electric Company

Nationality: American.

Born: November 19, 1935, in Peabody, Massachusetts.

Education: University of Massachusetts–Amherst, BS, 1957; University of Illinois–Champaign, MA, 1958; PhD, 1960.

Family: Son of John Welch (a railroad conductor) and Grace Andrews; married Carolyn Osburn, 1959 (divorced 1987); married Jane Beasley (an attorney), 1989 (divorced 2002); children (first marriage): four.

Career: General Electric Company, 1960–1968, engineer; 1968–1971, vice president and head of GE Plastics; 1971–1973, vice president of Chemical and Metallurical Division; 1973–1977, head of strategic planning; 1977–1979, senior vice president and head of Consumer Products and Services Division; 1979–1981, vice chairman; 1981–2001, corporate chairman and CEO and chairman of National Broadcasting Corporation.

Awards: Junior Achievement National Business Hall of Fame, 1997; Manager of the 20th Century, Fortune , 1999; 400 Richest Americans, Forbes , 2001–2004.

Publications: Jack: Straight from the Gut, 2001.

■ John F. Welch, Jr.—who went by the name Jack—was among America's most recognized and controversial chief executives. During his 41 years at General Electric (GE) Welch rose from his position as an entry-level junior engineer to become the company's youngest vice president and later its youngest CEO and chairman. Throughout his 20 years leading GE Welch garnered a reputation for having a no-nonsense and dynamic style that was at times considered abrasive by employees and the public alike. While the merits of Welch's management tactics were the subject of debate, none could argue with the results produced by his leadership. Welch took GE into international markets at a scale never before attempted while leading the company away from manufacturing and into

services. GE's market value grew 40-fold, to $500 million, between 1981 and 2001. At the end of 2001, which was the beginning of Welch's retirement, GE was the most valuable company in the world.

EARLY LIFE, EARLY LESSONS

Jack Welch was born in Peabody, Massachusetts, to a blue-collar Irish-Catholic family and was raised in Salem. An only child, the young Welch was the exclusive beneficiary of his parents' attention, for better or for worse. He attributed many of the fundamental life lessons he learned to growing up in his Salem neighborhood; some he learned from his parents, others from the neighborhood boys through sports. At an early age Welch discovered the premium he placed on winning and the bad taste left in his mouth by losing.

The role of sports in Welch's early life was profound; he would rely on lessons taken on the field time and again throughout his career. In his autobiography, Jack: Straight from the Gut , Welch described one instance in particular when his hockey team lost a game, to which he responded by throwing his stick and pouting. Immediately afterward Welch's mother marched straight into the locker room and took him to task in front of the team: "If you don't know how to lose, you'll never know how to win. If you don't know this, you shouldn't be playing" (2001).

After earning a bachelor's degree in chemistry from the University of Massachusetts and graduate degrees from the University of Illinois, Welch headed back to Massachusetts for a position with GE developing new plastics. Welch recalled work as an engineer at the Pittsfield, Massachusetts, facility as being fast paced and exciting; he was able to explore the limits of materials technology with only limited interference from distant management. The labs were small and intimate, and a charged, excited atmosphere encouraged achievement. Welch would remember that atmosphere and try to keep the same level of enthusiasm throughout his career.

But Welch's first job with the company was almost his last. He felt underpaid and undervalued, due partly to what he saw as a bloated GE bureaucracy, partly to the standard bonus he received when he felt he deserved more. In fact, Welch accepted a job offer from another company; however, only days before he was to leave GE he was convinced to stay by Reuben Gutoff. Gutoff, who later served as the president of Standard Brands and started his own consulting firm, was at the time a burgeoning executive who saw potential in the young engineer and sympathized with his position. Although he stayed on, Welch had not changed his mind about GE's administration, which he saw as unresponsive at best and debilitating at worst. Welch would struggle for the next 40 years to balance the need for effective administration against the needs for efficient production and market agility.

By 1968 Welch was running General Electric's entire plastics business, then a $26 million operation. He oversaw the production and marketing of Lexan and Noryl, trademarked materials developed in GE labs. The plastics became common in consumer goods thanks in no small measure to Welch's relentless sales efforts. The position was ideal for an energetic engineer with a doctorate in chemical engineering as well as an understanding of the business of science. Through the early 1970s Welch held increasingly challenging positions and moved swiftly through the company's ranks: he led the chemical and metallurgical division from 1971 to 1973; served as head of strategic planning for a $2 billion portfolio of businesses from 1973 to 1977; and was sector executive in the consumer-products division, a $4.2 billion operation, from 1977 to 1981.

LEADING GE

In 1981 Jack Welch was not considered a leading contender for GE's top job. However, his performance and earnings record ultimately won him the position over six other candidates. Even though he had no formal master plan for GE's reorganization, he did have a vision of what he wanted the company to be.

The first step in realizing that vision was a dismantling of the bureaucracy. At the start of Welch's tenure GE administration was built around three hundred separate businesses, a recipe for inefficiency. Welch tore into the ossified corporate structure with a vengeance and by the mid-1980s had overseen nearly 120,000 layoffs and earned the nickname "Neutron Jack." The name was derived from the neutron bomb, a weapon designed to minimize heat and blast effect but maximize dispersal of lethal neutron radiation—in effect, eliminating people but leaving buildings and equipment intact. Welch was never fond of the moniker.

Entire lines of business were dismantled or sold off under Welch's doctrine of exclusively maintaining operations that were ranked first or second in their given field. By 1985 billions of dollars had been made or saved through sales and layoffs. Welch sought opportunities for growth by reinvesting those billions and considered possible takeover targets. He eventually settled on RCA, originally a GE startup but at the time of the merger a top competitor in the high-tech and defense industries. The merger made sense as an effort to consolidate American manufacturing in those fields against Japanese competition. The deal was the largest merger of its kind in the history of American business, with RCA selling for nearly $6.3 billion. Within three years half of RCA's premerger workforce was gone, as well as most of its businesses, including the radio network, which had been in operation virtually since radio was born. By the late 1980s only the National Broadcasting Corporation (NBC) television network and RCA's defense businesses remained.

As the 1990s progressed Welch instituted the Six Sigma program at GE. Initially implemented at Motorola and Allied-Signal, the program was developed to maximize the efficiency of manufacturing processes through the minimization of production of defective units. When applied at General Electric it became the largest quality-control measure ever adopted in corporate America. The program required a huge investment in training and tracking but ultimately led to great gains in profit and productivity.

By the end of the century GE had developed an electronic-business program; another of Welch's initiatives, the system electronically tied the company directly to suppliers and customers. The e-business was just one aspect of what Welch dubbed the "boundaryless company," a company without administrative walls between separate business units and where knowledge applied to one area could be applied companywide. At the time of his retirement Welch had only begun to see his vision of a boundaryless company come to fruition.

MANAGEMENT STYLE

Jack Welch firmly believed that top performers deserved to be handsomely rewarded, an attitude he had retained since his first job at GE. He established a performance-review program to identify the top 20 percent of employees, who were accorded bonuses, as well as the bottom 10 percent, the "lemons," who were typically fired and replaced. Welch supported the distribution of wealth as far as possible throughout the company and understood when considering bonuses that life-changing fortunes were sometimes at stake.

Besides the raw numbers measuring efficiency and profits, more personal aspects also characterized Welch's leadership. He brought an air of informality to the company that stemmed from his belief that General Electric was little different in practice from a small local market. Customer satisfaction and positive relationships with both customers and employees were what ultimately made a business successful. Whether the product for sale was turbines or apples, the customer would determine the success of the enterprise. Thus, Welch made efforts to cultivate relationships with suppliers, customers, and employees alike. Knowing his employees had a direct impact on productivity, Welch communicated with workers often enough for them to feel that at any moment they could receive a note or a visit from the boss. His efforts at communication engendered senses of value and pride in employees, in that if a task was important enough for Welch to care about, it was important enough to perform with the utmost effort. As a result of his personability, everyone knew Welch simply as "Jack."

Informality was also standard in company correspondence. Welch faxed handwritten notes to anyone in the company who he felt deserved personal communication, whether to motivate, correct, or congratulate, from top management to laborers. Welch also personally reviewed everyone who worked directly for him, handwriting extensive performance evaluations that sometimes ran several pages. This exercise not only gave specific and ongoing feedback to employees but was a chance for Welch to reflect on the businesses that each employee was leading. The atmosphere of informality was perhaps most critical among GE's top leadership, where the confidence that came from being in familiar company encouraged executives to openly praise or criticize each other—or even Welch himself.

THE CULTURE OF COMPETITION

But informality could not have been mistaken for laxity, or kindness for weakness. Previous GE leadership had delineated management concepts designed to guide the company through the subsequent year in formal annual presentations. As part of his sustained war against entrenched bureaucracy Welch dispensed with this system entirely in favor of more continual general guidance. Under Welch's leadership formal meetings and deliberative committees were no longer needed in order to implement change. More authority was entrusted to lower-echelon leaders, who were more familiar with immediate problems and possible solutions than were distant senior executives. The new system allowed greater latitude for managers and the opportunity for swifter responses in order to meet rapidly changing conditions.

Within this system of fast-moving goals and changing tactics, Welch sometimes felt as though he were back in the vacant lot of his youth. In the "Pit," where he and his neighbor-hood friends often played their games, the future GE chief executive first learned both to lead and to follow. Later he frequently applied sports metaphors to his thinking and in his relations with managers. At times he considered himself a team captain, picking the best players for the GE team and drawing the most out of them once the game had begun. Welch consistently forced executives to argue in meetings, often heatedly, the idea being to force management to know their businesses, processes, and issues thoroughly before engaging in discussion with the boss. Under such conditions Welch could determine a manager's level of commitment or enthusiasm for a project or policy by noting the extent to which he was willing to argue. Welch was typically curt and had little patience for half measures and was similarly combative in performance-review meetings, in which company leaders would discuss the employees within their respective divisions. Welch could be quick to make judgments with seemingly limited knowledge, but he sought to provoke advocacy from his management and ultimately trusted them to tell him when he was wrong.

Despite media perceptions of him as an ogre, Welch himself disputed the notion that he was a particularly brash boss. He insisted that there was a difference between being "tough minded" and "bullying" and deplored the notion that GE inculcated an atmosphere of bellicosity or machismo for its own sake.

EDUCATION

Ivy League educations and MBAs were no guarantees of success at GE under Jack Welch, which would come as no surprise considering that his training was in science and his degrees were from state schools. He took education seriously but was more concerned with cultivating talented managers who could run successful businesses.

As evidence of the seriousness with which Welch viewed corporate education, he developed an executive-training facility at Croton-on-Hudson, dubbed "Crotonville," in upstate New York. Welch turned the 52-acre facility that was originally designed and built by earlier company leadership into a prep school for current or potential leaders. The move was a bold one, as Crotonville training had not traditionally been a valuable commodity and had not necessarily attracted the company's best and brightest. Furthermore, in the midst of GE's downsizing the site required millions in order to be refurbished, upgraded, and expanded. Welch persuaded the board to fund the project, to which upwards of $40 million was eventually committed. To Welch the cost was negligible; he gambled that the return on the investment—talent—would be more valuable than money.

Welch originally spent several hours every month leading discussion in what became called the new "Pit," the large, sunken lecture hall at Crotonville. In time, advisors from Harvard and the University of Michigan were brought in to restructure the Crotonville experience, starting with the general curriculum and later with specific coursework. They dispensed with case studies of other companies in favor of the study of specific problems within GE. There were several three-week programs developed for leaders at various stages in their careers, with others built around the study of a particular country or industry. Over time GE enlisted a cadre of experts who were already on the payroll to make themselves available to advise on the issues and questions studied at Crotonville. Within 10 years of Welch's Crotonville redevelopment only the top performers landed the increasingly competitive slots to attend the training programs; by 2001, 85 percent of the Crotonville faculty were GE executives.

THE "BOUNDARYLESS" COMPANY

While thousands of students attended training at Crotonville in order to devise solutions to business problems, implementation of the lessons taken there remained unenthusiastic. Characteristically, Welch blamed bureaucracy for thwarting his vision—in this case managerial holdouts from the previous era who did not share Welch's broader vision for the company. Those managers were not nearly as impressed by Crotonville alumni as Welch was. Frustrated, Welch applied the "Pit" experience across the entire company. Welch wanted not large, formal classrooms and management training but forums for the same types of exchanges of ideas that he deemed so valuable at Crotonville. Welch named the gatherings "Work-Outs" and modeled them on the traditional New England–style town meeting. The twist was that management would be excused from the discussion. Facilitators hired from academia to lead discussion helped workers develop solutions to ongoing problems within the business. At the ends of the meetings managers were brought back and presented with the results of the discussion. On the spot they had to decide to either implement the arrived-at solutions or not; they had to be prepared to either argue against the proposals or, if unable to execute them immediately, construct a timetable for doing so.

As "Work-Outs" spread throughout GE and Welch saw more good ideas being implemented, he started to ponder his notion of the "boundaryless" company. Welch envisioned a system where not only the inventor of a good idea but all the others who recognized and developed that idea would be rewarded. In practical terms this meant that knowledge needed to be shared across all lines of business, which in turn necessitated more sharing of the employees themselves across different businesses. "Knowledge" in this context referred not only to factual information but to methods of improving profitability, the insight to recognize problems, and experience in correcting past problems. With maximum communication, lessons and ideal practices learned in one division could be applied to any other division.

In essence three methods encouraged this continuous redistribution of knowledge. Firstly, Welch broadened the granting of stock options beyond GE's top leadership. Options were far more valuable than cash bonuses in a strong market and thus were a strong incentive to employees. These options also tied the success of GE to the promotion of the best ideas produced within the company. Secondly, meeting and planning sessions held throughout the year at all levels of management allowed new ideas to be presented, refined, and applied. Finally, Welch brought in human resources, adding consideration of boundaryless behavior to performance reviews. Whoever was insufficiently imaginative or reluctant to embrace Welch's vision was dismissed.

Welch believed that if he wanted his messages to have the desired impact he needed to disseminate them himself. He recognized, however, that it was impossible to develop personal relationships with every employee in the company. What Welch chiefly achieved through his corporate-education initiatives and his pursuit of the boundaryless company was the institution of a means of communication. Welch's messages and visions were learned and reinforced first at Crotonville, then through the sharing of employees across businesses and in ongoing meetings; ultimately these concepts were tied to employee promotion and retention. Welch trusted managers to relay leadership messages throughout the company, but he did not rely solely on them to do so.

See also entry on General Electric Company in International Directory of Company Histories .

sources for further information

Byrne, John, "How Jack Welch Runs GE," BusinessWeek , June 8, 1998.

Lowe, Janet, Jack Welch Speaks: Wisdom from the World's Greatest Business Leader , New York, N.Y.: Wiley & Sons, 1998.

Slater, Robert, Jack Welch and the GE Way: Management Insights and Leadership Secrets of the Legendary CEO , New York, N.Y.: McGraw Hill, 1998.

Slater, Robert, The New GE: How Jack Welch Revived an American Institution , Homewood, IL: Business One Irwin, 1993.

Welch, Jack, Jack: Straight from the Gut , New York, N.Y.: Warner Books, 2001.

—Thomas R. Borjas

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: