SIC 3479

COATING, ENGRAVING, AND ALLIED SERVICES, NOT ELSEWHERE CLASSIFIED

This industry includes establishments primarily engaged in performing the following types of services on metals, for the trade: (1) enameling, lacquering, and varnishing metal products; (2) hot dip galvanizing of mill sheets, plates and bars, castings, and formed products fabricated of iron and steel; hot dip coating such items with aluminum, lead, or zinc; retinning cans and utensils;(3) engraving, chasing, and etching jewelry, silverware, notarial, and other seals, and other metal products for purposes other than printing; and (4) other metal services, not elsewhere classified. Also included in this industry are establishments that perform these types of activities on their own account on purchased metals or formed products. Establishments that both manufacture and finish products were classified according to the products.

NAICS Code(s)

339914 (Costume Jewelry and Novelty Manufacturing)

339911 (Jewelry (including Precious Metal) Manufacturing)

339912 (Silverware and Plated Ware Manufacturing)

332812 (Metal Coating, Engraving, and Allied Services (except Jewelry and Silverware) to Manufacturing)

Industry Snapshot

The larger firms that participated in this industry were often more diversified in their finishing activities, while independents tended to specialize in one or two

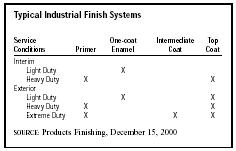

| Typical Industrial Finish Systems | ||||

| Service Conditions | Primer | One-coat Enamel | Intermediate Coat | Top Coat |

| SOURCE: Products Finishing, December 15, 2000 | ||||

| Interim | ||||

| Light Duty | X | |||

| Heavy Duty | X | X | ||

| Exterior | ||||

| Light Duty | X | X | ||

| Heavy Duty | X | X | ||

| Extreme Duty | X | X | X | |

types of finishing. During the 1950s and 1960s, there was a tendency for manufacturing firms to set up their own finishing operations. With the increased environmental regulation of the industry beginning in the 1970s, many manufacturing firms opted to subcontract for finishing services, thus getting around the added costs of waste treatment. Parts to be finished were typically shipped to finishing firms by their customers, after which they were shipped back. Since the mid-1970s, about three-fourths of a finishing firm's business came from within a 50-75 mile radius of the firm. Since finishers needed to be near their customers, their operations were located in the same areas as producers of durable goods.

Organization and Structure

Just over half of the output of this industry consisted of the application of organic coatings such as paints, varnishes, and lacquers. Next to the application of organic coatings, galvanizing was the largest activity in the industry, making up 22 percent of output. Metal coating and allied services, not specified by kind, made up 21 percent of output. The remaining 6 percent consisted of engraved and etched products.

The industry was served by the National Association of Metal Finishers (NAMF), located in Chicago and founded in 1955. The American Galvanizers Association (AGA), founded in 1935, also served the industry. In 2004, the NAMF, the American Electroplaters and Surface Finishers Society (AESF), and the Metal Finishing Suppliers Association (MFSA) planned to consolidate at the start of 2005.

Background and Development

The industry's primary focus is the application of coatings including paint, lacquer, and varnish. Although metals had been coated by like means since ancient times, their modern application was dependent on the development of phosphating as a surface preparation. Phosphating involved treating a metal, usually steel, with phosphoric acid. This greatly improved the adhesion and durability of coatings. Phosphating alone was also used as an anti-corrosive coating on steel in conditions where the potential for corrosion was not high. Although phosphating was developed in the 1860s, treatment times were exceedingly long until iron filings were added to the phosphoric acid bath after 1906 (following Thomas Watts Coslett's patent), shortening treatment time to about 2.5 hours. The treatment time was shortened to 10 minutes by the addition of copper salts in 1929, after which the process became generally used as a surface preparation for organic coatings. More recent developments lowered treatment times to just 5 seconds.

Galvanizing is the process of dipping steel or iron into a bath of molten zinc. The zinc coating served as a corrosion prohibitor, and was applied to structural parts, sheeting, pipe, various containers, and hardware. During this process, the metal to be coated was immersed until it reached the same temperature as the bath (typically 1,562 degrees Fahrenheit). Thus, the process could not be used on springs or other objects in which desirable properties would be lost by such exposure to heat. Since uniformity of thickness was not readily controllable in hot dip processes, galvanizing was limited to applications in which such uniformity was not required. Electroplating with zinc was sometimes also referred to as galvanizing or electrogalvanizing. This process was done cold, and could assure high uniformity of thickness, getting around the aforementioned problems.

As with all metal-coating processes, it was vital that parts were thoroughly cleaned before being galvanized. This typically involved treating the parts to be galvanized in an acid bath, after which they were fluxed, a process that generally used hydrochloric acid. The wastes produced by such pre-treatment were toxic, as were the solvents used in the organic coatings processes. The minimization of such wastes continued to be central issues for the industry, as did the development of alternative solvents.

The industry received a boost in the early 1990s with the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991, which required that all highways, bridges, and tunnels built with federal funds take into account the costs of materials over their lifecycles. This strongly favored the use of galvanized metals. The American Galvanizers Association estimated early in the decade that use of galvanized steel would double through the 1990s, largely as a result of increased use for highways, bridges, and wastewater treatment systems.

The industry was also strongly affected at the end of the twentieth century by increased concerns about the environment. The most promising of the environmentally friendlier alternatives to electroplating were the application of metal powders and vacuum deposition, processes that were projected to become increasingly important. Thus, the effects of environmental regulation provided substantial benefits to the industry, and growth prospects appeared promising. From the perspective of the firms, the question remained whether plating or coating firms could more readily diversify into these technologies.

The relative ease of entry into the industry made for highly competitive conditions in which small independents were sandwiched between the large suppliers of finishing machinery and materials and the large firms for which they provided services. This meant relatively low profits for independents. Profit rates varied greatly among firms in the industry. Taking rates of return on equity, a firm ranking at the median had less than half the profitability of a firm ranking at the upper quartile.

The value of product shipments in 1995 was approximately $7.0 billion, up from $4.9 billion in 1990. Growth of output and employment stagnated entering the 1990s, but profit rates remained close to the average for the period 1982 to 1992. The industry benefited from growth in the use of galvanized steel and in the use of alternatives to electroplating that it offered.

Theoretical knowledge, as opposed to empirical knowledge, rapidly increased in importance in the 1990s. Equipment and material suppliers developed many new techniques. Thus, smaller firms were able to obtain some of the same innovations as larger firms. Nonetheless, given the greater purchasing power of the captive and large independent firms, suppliers allocated a disproportionate amount of their research and technical support to such firms.

Another issue inhibiting investment by smaller firms in more capital-intensive techniques was that, unlike large captive firms, they were less able to absorb the losses resulting from excess capacity in the face of an economic downturn. Because the greater profitability of the more successful firms could be used to finance techniques that were more productive and sophisticated, the gap between large captive firms and smaller independents was likely to remain, if not widen.

The industry continues to be strongly influenced by environmental factors, and innovative techniques continue to effect finishing processes. With shipments valued at $8.5 billion in 1997, the industry showed steady growth from the beginning through the end of the 1990s.

Starting in early 1997 and continuing into the 2000s, the National Metal Finishing Strategic Goals Program allied the industry with the Environmental Protection Agency and other environmentalists to cooperate in creating blueprints of how best to solve the environmental challenges facing the industry. Instead of working as adversaries, the groups worked together to devise and implement realistic guidelines for issues such as the storage, recycling, and disposal of wastewater treatment sludges. Often, the industry had better solutions to the problems than the EPA or environmentalists could suggest, since the industry best understood its own processes. In this sense, the Goals Program sought to move beyond compliance in ways that benefited the industry and the EPA, and also satisfied environmentalists.

Current Conditions

As with most manufacturing industries, the concerns in the mid-2000s were related to competition from foreign markets and trade issues. Particular to the steel industry, tariffs were impacting both employment and industry production in a negative way, hindering efficiency and bottom line economics. This, in turn, adversely affected those in metal finishing industry, as finishers were both losing money in the form of discounted prices and losing business completely.

Because the industry needed to comply with regulations from the government, new coatings and methods of handling were being developed in the 2000s. Metallized materials were coming into more frequent use as well. While electrocoating and powder coating remained the leading processes, many companies in this industry offered diversified finishing services rather than specialization in one area, due to the changing tastes and wishes of the customer base and the need to keep the business they had in a shaky market. According to Industrial Paint and Powder , although many manufacturers put time and effort into the actual production, they tended to forget that "the finish is the first thing that catches the eye of the potential consumer."

Industry Leaders

Leading the industry in overall sales for 2001 was Crown Group Inc. of Warren, Michigan, with $290 million in sales and 800 employees. In second place was St. Louis-based Precoat Metals, with $208 million in sales and 800 employees. Rounding out the top three was Acheson Colloids Company of Port Huron, Michigan, with $165 million in sales and 900 employees.

Employment for the miscellaneous manufacturing industry as a whole was projected to rise to 387,000 by 2012, a tiny but steady annual growth rate of one-tenth of a percent.

Research and Technology

As with the metal-plating industry, a number of innovations in the metal-coating industry were motivated by increasingly pressing environmental regulations. For the process of stripping coatings from rejected parts, blasting with plastic particles was seen as a viable alternative to the more toxic methods of chemical stripping and incineration. In the early 1990s, Whirlpool Corp. installed a pre-treating line in its Evanston, Illinois, plant that made use of a safer alternative to traditional phosphating. The line used a chrome-free rinse and cleaners that lessened the production of heavy metal wastes. The new line also improved the quality of coatings and consumed less energy.

New developments in the deposition of metal coatings were expected to cause a shift away from electroplating to alternative methods, such as new forms of vacuum deposition. This process involved reducing pressure in a closed container to produce a vacuum in which pure metals could be vaporized at low temperatures and then allowed to condense on a surface. Laboratory tests of new vacuum methods produced high-quality coatings with fast coating times. Vacuum coating also had a significant advantage in that it did not generate the toxic sludges of electroplating processes. Another technology of increasing importance was the application of metal powders by spraying or through the use of centrifugal force. As with vacuum deposition, such applications of metal powders had the significant advantage of not producing toxic sludges.

While the initial costs of pollution abatement technologies may have been prohibitive to some firms, a number of these technologies could lower production costs. The BASE Corp. reported that pollution abatement measures at two of its coating plants saved it $1.3 million in the early 1990s, and that the payback period after initial investments ranged from 15 to 20 months. New technologies in the application of powder coatings made them not only an environmentally friendlier, but also a cost-effective alternative to electroplating.

Further Reading

"2000 Large Coating Job Shop Survey." Industrial Paint and Powder , December 2002.

Baker, Deborah J., ed. Ward's Business Directory of US Private and Public Companies. Detroit, MI: Thomson Gale, 2003.

Izzo, Carl. "Overview of Industrial Coating Materials." Products Finishing , 15 December 2000.

Kline, Steven R. Jr. "2000 Large Coating Job Shop Survey." Products Finishing , October 2000.

Llewellyn, Dr. William. "Metallized Materials." Paper, Film, and Foil Converter , March 2002.

National Association of Metal Finishers. "AESF, MFSA and NAMF Consider Consolidating Into One Industry Organization by January 1, 2005." News , 5 February 2004. Available from http://www.namf.org/news/consolidate.cfm .

——. "Plating Exec Jim Jones Testifies Before ITC on Negative Impact of Steel Tariffs." News , 12 August 2003. Available from http://www.namf.org/news/jimjones.cfm .

——. "U.S. Manufacturing Plight is Focus of Fall Legislative Conference." News , 12 August 2003. Available from http://www.namf.org/news/consolidate.cfm .

Patry, John. "Maximizing Efficiency in Metal Finishing." Industrial Paint and Powder , December 2002.

U.S. Census Bureau. 1997 Economic Census—Manufacturing. Washington: GPO, 2000.

U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Economic and Employment Projections. 11 February 2004. Available from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/ecopro.toc.htm .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: