SIC 2261

FINISHERS OF BROADWOVEN FABRICS OF COTTON

This category covers establishments primarily engaged in finishing purchased broadwoven cotton fabrics or finishing such fabrics on a commission basis. These finishing operations include bleaching, dyeing, printing (roller, screen, flock, plisse), and other mechanical finishing, such as preshrinking, calendering, and napping. Also included in this industry are establishments primarily engaged in shrinking and sponging of cotton broadwoven fabrics for the trade and chemical finishing for water repellency, fire resistance, and mildew proofing. Establishments primarily engaged in finishing wool broadwoven fabrics are classified in SIC 2231: Broadwoven Fabric Mills, Wool (Including Dyeing and Finishing); those finishing knit goods are classified in knitting mill industries; and those coating or impregnating fabrics are classified in SIC 2295: Coated Fabrics, Not Rubberized.

NAICS Code(s)

313311 (Broadwoven Fabric Finishing Mills)

Industry Snapshot

Roughly 300 U.S. establishments engaged in dyeing and/or finishing of broadwoven cotton fabrics in the early 2000s. Employment in this industry totaled 45,031 in 2000, down from 51,447 in 1997. Nearly half of these establishments employed 20 or more workers. The vast majority of them were located in the southeastern United States, particularly in North Carolina and South Carolina (15). Some establishments, such as Burlington Industries Inc., Cone Mills Corp., and Thomaston Mills Inc., were engaged in both manufacturing and finishing of broadwoven cotton fabrics. Some companies, such as Cranston Print Works, were engaged only in the dyeing and finishing of broadwoven cotton fabrics.

More than 95 percent of manufactured broadwoven cotton fabrics receive some form of dyeing and/or finishing treatment. Even industrial products that require no coloration still require some type of finishing process to render the fabric useful in its intended application. In the early 1990s, environmentally conscious products began attracting consumer attention. Sheets and pillowcases that were produced without dyeing or chemical processing became popular in department stores. But even these products necessitate a finishing process, albeit one without chemicals, to become useful bedding products.

Organization and Structure

The finishing of broadwoven fabrics is subdivided into three general processing categories: fabric preparation, fabric coloration, and fabric finishing. Fabric preparation consists primarily of bleaching and preparing fabrics with chemical agents to aid in subsequent processing. Such processes, depending on the end result desired, may be performed in open-width fabric form or in fabric rope form.

Coloration of fabrics consists of a variety of dyeing methods executed via batch or continuous process procedures and printing. Printing of broadwovens may be performed by screen printing machines, roller printing machines, roller-screen printing machines, or by a process known as transfer printing.

Fabric finishing is accomplished either through surface (dry) finishing or wet finishing. Surface or dry finishing consists of such processes as sueding, sanding, and napping and imparts a certain texture or feel to the fabric. Wet finishing consists of preshrinking or sanforizing, mercerization, or heat-setting. Chemical finishes for water repellency, flame retardancy, mildew proofing, and wash-and-wear characteristics are applied during finishing processes. Fabric straightening (elimination of bow and bias) and width setting is also performed during finishing.

Virtually all establishments engaged in dyeing and finishing of broadwoven cotton fabrics have at least part of their operations involved in commission work—dyeing and finishing services performed on fabrics owned by other companies. Dyeing and finishing facilities generally utilize much more complicated production processes than do facilities designed for other textile processes. This is due both to the volume of water used in dyeing and finishing operations and the amount of chemicals used in each dyeing and finishing process. Dyeing and finishing machines and equipment are generally custom-designed to meet specific applications and needs. Piping requirements for water, steam, and chemicals will vary from one installation to another as well. Therefore, building facilities used for dyeing and finishing operations are usually custom-designed. While buildings for other textile processes, such as yarn manufacturing, knitting, and weaving, carry structural specifications due to the weight and vibration potential of the machines, dyeing and finishing building specifications must consider machine weight plus machine and piping design and configuration.

Establishments engaged in dyeing and finishing of broadwoven cotton fabrics generally serve three market categories: apparel, home furnishings, and industrials. In the United States, apparel and home furnishings account for 75 to 80 percent of the broadwoven cotton fabric production. Imports are eroding those markets, however, at a time when industrial fabrics are growing in end uses. Some industry observers expect industrial fabrics to account for approximately 35 percent of production by the early 2000s.

In the apparel area, companies dye and finish broadwoven cotton fabrics for men's and ladies' shirts and blouses, children's wear, men's trousers and ladies' pants, leisure and sportswear, and other clothing. Because of some advances developed by Cotton Incorporated, the research arm of the Cotton Growers' Association, companies can now produce water repellent broadwoven cotton rainwear. Cotton Incorporated has also developed some finishes that allow production of wash-and-wear (easy care, no-iron) cotton fabrics.

In home furnishings, dyers and finishers of broadwoven cotton fabrics supply bedding products (sheets, pillowcases and shams, light comforters and blankets, and dust ruffles); bath products (bath towels, hand towels, and wash cloths); and other household items such as draperies and curtains, napery products (napkins and tablecloths), kitchen towels, upholstery fabrics, and cushion covers. In the industrial area, broadwoven cotton fabrics are dyed and/or finished toward production of medical and hospital goods, abrasive fabrics such as sanding belt fabrics, conveyor belts, tents, awnings, luggage, and other products.

Background and Development

Along with immense technology advancements, trade agreements during the 1990s had a significant impact on finishers of cotton broadwoven fabrics. Trade agreements enacted in the early 1990s gave the industry the opportunity to compete in the global marketplace through effective brand recognition and marketing together with capital investments in systems such as Demand Activated Manufacturing Architecture (DAMA) that increase efficiency.

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which reduced or eliminated tariffs among 117 nations throughout the 1990s, will not, according to American Textile Manufacturers Institute (ATMI) officials, have a positive impact on U.S. producers of dyed and finished broadwoven cotton fabrics. However, since global textile usage could grow dramatically in the future due to developing economies and increasing populations, how much of a negative impact this agreement will have on U.S. dyers and finishers remained to be seen.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), enacted in 1993, which essentially removes all trade restrictions among Canadian, American, and Mexican businesses, had a positive economic effect for U.S. dyers and finishers of broadwoven cotton fabrics. North American countries were the U.S. textile industry's most important export markets throughout the 1990s, and Mexico was expected to continue to be a growing market.

By the end of 1999, the textile industry as a whole continued to be influenced by global trade conditions and the demands of certain markets. The ATMI reported at the end of 1999 that textile shipments had decreased in 1998 and 1999 as a result of competition from low-priced Asian textiles. Asian textile prices fell by 6.5 percent, negatively impacting the American textile market. On the other hand, American textile imports to Mexico continued to grow and had increased 19 percent during the first ten months of 1999. By the end of 1999, Mexico and the Caribbean Basin Initiative (CBI) region remained the two largest American textile export markets. Textile shipments in 1999 decreased, continuing a trend from 1998. American textile shipments during 1999 fell 3 percent to total $7.8 billion.

Current Conditions

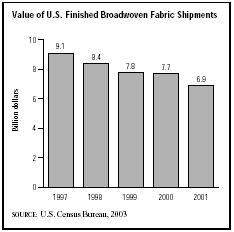

Along with increased international competition, domestic conditions began to impact the industry negatively in the early 2000s. As the U.S. economy weakened, the textile industry faced not only a growing number of inexpensive imports, but also waning demand. U.S. Census Bureau statistics indicated that the value of finished broadwoven fabric shipments declined throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s, falling from $9.1 billion in 1997 to $6.95 billion in 2001. Reflecting this downward trend, broadwoven fabric production declined from 13.2 billion square yards in 2001 to 12.5 billion square yards in 2002, according to the American Textiles Manufacturers Institute. These figures reflected a broader industry downturn: between 1997 and 2002, more than 200 textile mills shuttered operations, dropping U.S. textile employment to 435,000, compared to 489,000 just a year earlier.

Many leading textiles manufacturers struggled throughout the early 2000s. For example, after five years of consecutive losses, Thomaston Mills Inc. liquidated operations in 2001. Sales for another industry giant, Greensboro, North Carolina-based Burlington Industries Inc., declined 29 percent in 2002 to $993 million, and the firm posted a $100.8 million loss. In 2003, Burlington filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. W.L. Ross and Co. paid $614 million for the troubled firm later that year. Similarly, Cone Mills Corp. filed bankruptcy in 2003 and was acquired for $90 million by W.L. Ross and Co. in 2004.

Industry Leaders

The largest company engaged only in finishing broadwoven cotton fabrics was Cranston Print Works headquartered in Cranston, Rhode Island. In the early 2000s Cranston Print Works had sales that ranged from $100 million to $250 million. The next two largest companies in this industry, both with an estimated $55 million in sales, were Santee Print Works headquartered in Sumter, South Carolina, and Cecil Saydah Co. headquartered in Los Angeles, California.

Workforce

Pressure from low-priced Asian textiles had its impact on the American textile industry work force. According to the ATMI, textile industry employment continued to decline in 1999 to an average of 562,000 workers. This represented a 6 percent decrease in the textile work force from 1998. The work week in the industry also changed, with the average hours worked decreasing 7 percent during 1999. Employment in the broadwoven fabrics sector dropped from 51,447 in 1997 to 45,031 in 2000. Production workers numbered 36,051.

Economic census data from 2000 showed an average of 65 employees per establishment for SIC 2261, with an average wage of $9.20 per hour. For the broader industry classification SIC 226, textile draw-out and winding machine operators comprised the largest percentage (30.6 percent) of occupations in the industry.

Research and Technology

As a part of industry-wide efforts to remain competitive in the international arena, cotton broadwoven fabric finishers have explored several new operating systems. One such system, called Quick Response, demonstrated throughout the 1990s that as a communications process it could boost production of U.S. made broadwoven cotton products. The Quick Response system required partnerships throughout the soft goods pipeline—fiber producers, textile manufacturers, apparel manufacturers and retail establishments—and made use of electronic technology, especially bar coding and Electronic Data Interchange (EDI), to receive up-to-date information. This immediate market feedback enabled every member of the pipeline to reduce inventories, shorten delivery times between each pipeline partner, and eliminate processing steps at some partner members' operations without adding them at others.

The system also permitted orders from retail establishments that were smaller than season requirements and enabled these retail establishments to reorder in midseason after buying trends and patterns had been established. This process, when all elements were in place, reduced costs at all pipeline partner establishments and reduced the number of necessary markdowns at the end of the season in the retail establishments.

The American Textile Partnership (AMTEX) also aided U.S. producers of dyed and finished broadwoven cotton fabrics throughout the mid-1990s. AMTEX enacted a pact in 1993 in which national laboratories, in conjunction with the U.S. Department of Energy, worked on selected projects with the U.S. textile industry and its research facilities to develop systems to make the industry more competitive.

The AMTEX project with the most immediate results was Demand Activated Manufacturing Architecture (DAMA), which expanded on the Quick Response system. Under the DAMA system, electronics informed pipeline partners of each garment sold by making use of point-of-sale data generated during scanning of barcoded hangtags. The DAMA pilot project began in September of 1996, and results have shown that the creation of an electronic marketplace will improve operations and reduce costs through controlling warehouse costs and inventory size and reducing wastes, while improving customer responsiveness and product development. The years of preparation with the Quick Response system have allowed the industry to quickly realize the competitive advantages of capitalizing on the national information super highway.

In 1995 Cotton Inc. cooperated with the Textile/Clothing Technology Corporation to create a new spray technique for finishing broadwoven cotton. The new technique, called "metered addition of chemicals" used some of the machinery already in operation to dip and dye cotton and garments. According to a representative of Cotton Inc., the new process equaled the quality of garment finishing using dipping or dying methods. Other benefits to the new process included a short time to carry out the spraying (20 minutes to complete a cycle of spraying), the complete use of all chemicals (which are absorbed by the material and not left as waster to be disposed of), and the accessibility of the process to smaller finishing establishments. The spraying process was particularly appealing to companies dealing in smaller finishing volumes, since chemicals could be premixed, eliminating the need for staff chemists. In 1995, a machine that could carry out the spraying process and handle up to 100 pounds of fabric was estimated to cost $21,000.

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, the industry also explored advances in drying finished textiles. Watlow Electric Manufacturing Company found that radiant panel heaters worked better than ceramic radiant heaters for drying silk screening on fabrics. The radiant panel heating process accomplished drying of finished fabric in half the time needed for the ceramic radiant heating process. According to Watlow Company, the manufacturers of the radiant panels, one finisher of textiles was able to reduce inventory with the new heating process.

Further Reading

"Quick Facts About U.S. Textiles." American Textile Manufacturers Institute, 2003. Available from http://www.atmi.org/Newsroom/qckfacts.asp .

U.S. Census Bureau. "Current Industrial Reports: Apparel 2002." August 2003. Available from http://www.census.gov/industry/1/mq315a025.pdf .

——. "Statistics for Industry Groups and Industries: 2000." February 2002. Available from http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/m00as-1.pdf .

——. "Value of Shipment for Product Classes: 2001 and Earlier Years." December 2002. Available from http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/m01as-2.pdf .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: