SIC 4731

ARRANGEMENT OF TRANSPORTATION OF FREIGHT AND CARGO

This category includes establishments primarily engaged in furnishing shipping information and acting as agents in arranging transportation for freight and cargo. Also included in this industry are freight forwarders, which undertake the transportation of goods from the shippers to receivers for a charge covering the entire transportation, and, in turn, make use of the services of other transportation establishments as instrumentalities in effecting delivery.

NAICS Code(s)

541618 (Other Management Consulting Services)

488510 (Freight Transportation Arrangement)

Industry Snapshot

Companies engaged in the freight transportation arrangement business offer numerous services, ranging from import advice to shrink-wrapping freight crates. These firms are transportation middlemen that support the movement of cargo through the services they offer. Although relationships between forwarders and carriers may develop, the companies involved in arranging freight transportation are not affiliated with any particular carrier.

Automation, consolidation of information, and a strong customer orientation were the hallmarks of the industry in the 2000s. Freight transportation arrangements were rendered by two major types of establishments: freight forwarders and customs brokers. Although many large companies offered both types of services, the businesses were distinct.

Organization and Structure

Freight Forwarders. Freight forwarders operate under many names and licensing requirements. All freight forwarders, however, are transportation intermediaries that arrange the movement of cargo according to customers' needs. Supplementary services such as shipment tracing, warehousing and storage, and the preparation of letters of credit also are offered by forwarders. Freight forwarders often are referred to as "transportation architects."

Through working with numerous air, road, rail, and water transportation companies, these establishments endeavor to find the least expensive and most efficient freight routings possible. Their services are popular with shippers because freight forwarders are not affiliated with one carrier and therefore are not biased or restricted. Also, forwarders are known for their expertise in the ever-changing regulations that affect cargo movements, such as hazardous goods handling, documentation, and insurance. The carriers, in turn, welcome the business from forwarders. In fact, smaller carriers, who cannot afford to maintain sales staffs, depend on the business tendered by forwarders.

All forwarders that are involved in ocean, truck, or rail forwarding must be licensed by either the Federal Maritime Commission (FMC) or the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC). However, the majority of freight forwarders are licensed by the Federal Maritime Commission as ocean freight forwarders. Some ocean freight forwarders, known as non-vessel operating common carriers, operate as third party carriers and issue their own bill of lading. Since deregulation of the U.S. air transportation industry, air freight forwarders have not been subject to formal licensing requirements; however, most air cargo agents that are involved in international forwarding are endorsed by the International Air Transportation Authority (IATA).

Customs Brokers. Customs brokers provide services to importers and exporters and facilitate the clearance of shipments through customs. One particularly important service offered by a licensed customs broker is advice on regulations and laws pertaining to customs clearance and the power to argue on behalf of a client during the clearing process. In this regard, a customs broker is similar to a lawyer. Brokers may also provide advice and information on quotas for controlled commodities, trademark restrictions, and dumping duties, among other topics.

The customs brokerage industry is highly regulated by the U.S. Department of the Treasury. According to Section 641 of the Tariff Act, customs brokers must be individually and personally licensed by the Treasury, and brokerage firms must obtain a separate license. In order to be licensed, an individual must pass a comprehensive test, which often is passed by fewer than 40 percent of the test-takers.

Financial Structure. The rate structure for both freight forwarders and customs brokers is extremely competitive. These establishments operate on very thin profit margins. Freight forwarders generate revenue through transportation charges, fees for additional services such as warehousing or shrink-wrapping freight, and commissions from carriers. Customs brokers' revenue sources include document preparation fees, charges for customs clearance, and charges for post clearance services.

Background and Development

Pack horses were the primary means of transporting freight over land through the seventeenth century. In the mid-to-late eighteenth century, the first freight transportation establishments sprang into existence as services via pack horses. Ironically, supplying pack horse freight transportation frequently cost more than current airline freight rates. Even though traveling over land entailed a much shorter distance east to west than using water routes, the latter was much more practical and cost effective, so the majority of freight was moved over the Mississippi River, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Atlantic Ocean.

In the first half of the twentieth century, the United States mainly relied on truckers, oil pipelines, and inland-waterway carriers for freight and cargo transport. In the 40-year period from 1915 to 1955, railroad freight traffic decreased by 29 percent (as measured in ton-miles). Airlines accounted for less than 1 percent of freight transportation. Yet, the total freight traffic increased approximately 350 percent as a result of the boom in commerce and manufacturing.

Transportation middlemen, performing services similar to modern freight forwarders, operated in Europe in the 1600s. In the United States, these intermediaries arranged transportation by means of stagecoach, river boat, horse, and rail in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. However, the birth of the modern freight forwarding industry in the United States did not occur until after World War II, when the IATA allowed air freight forwarders and air cargo agents to solicit freight independently of the air carriers.

The deregulation of the trucking industry in 1980 contributed to a tremendous proliferation of forwarders. Deregulation resulted in a staggering increase in the number of registered truckers, causing confusion in the shipping community. Freight forwarders were needed to help shippers choose from the many newly established trucking companies. As a result, the number of forwarders swelled from 70 in 1980 to 6,000 in 1991. Many of these forwarders were small and barely solvent.

The growth of intermodal traffic during the 1980s and early 1990s also contributed to a rise in the number of forwarders. Intermodal transportation, or the movement of freight via two or more modes of transportation, grew faster than the economy in 1992. Freight forwarders were particularly well-received in the intermodal industry because of their willingness to take responsibility for the cargo as it moved over different modes of transportation. In this way, one bill of lading was issued for the shipment. In 1992, between 400 and 500 forwarders handled approximately 35 percent of all rail intermodal traffic.

Although customs brokers operated as far back as Phoenician times, they have only operated since the early 1900s in the United States. The existence of customs brokers in the modern world can be attributed to myriad tariff laws that the United States and other countries enforce. In 1989, every shipment imported into the United States was subject to 500 pages of customs regulations and 14,000 tariff items. Moreover, importers must comply with regulations put forth by approximately 40 U.S. regulatory agencies, such as the Food and Drug Administration and the Federal Communications Commission.

The demand for freight forwarders has remained stable. However, forwarders and customs brokers have found it difficult to maintain their profit margins, which are estimated to range between 5 and 10 percent. Lower freight rates reduced the commissions forwarders earned from the carriers. Additionally, the costs of automation and improved customer service eroded profit margins. Overall, forwarders and customs brokers significantly improved their service level without a corresponding increase in their rates.

The safeness of cargo and the adequacy of inspections has been an issue in recent years. Freight is only subject to inspection when the shipper is unknown to the freight forwarder; shippers familiar to freight forwarders comprise 80 percent. However, most cargo shipments are not X-rayed or inspected as a matter of routine, and hazardous materials inspectors lack proper training.

In 1989 the Presidential Commission on Aviation Security issued the recommendation that airlines, rather than freight forwarders, be responsible for screening cargo. Until that time, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) stipulated that freight forwarders comply with a security program. However, that stipulation went largely unenforced because the Civil Aeronautics Board became defunct in 1984, and it was their responsibility to monitor freight forwarding firms. In 1992, the FAA suggested ways to make freight forwarders accountable for security. Then, in 1994, the FAA began requiring that airlines only conduct business with air forwarders who submit safety plans that adhere to a set of established federal guidelines.

The globalization of the market created challenges for forwarders and brokers. Logistics appeared to be the smallest hurdle, while increased competition from large integrated carriers—who took full responsibility for cargo and promised shippers door-to-door service over great distances—was more difficult for forwarders and brokers to overcome. To mitigate this threat, forwarders and brokers continued to emphasize their ability to provide the customized service not offered by mega-carriers. Freight transportation arrangers, however, established more overseas networks in response to this globalization.

International shipments—13 million per day in 1999—were growing at 18 percent annually. However, to avoid potential delays in the end-to-end transport of goods, companies were turning more and more to over-night air shipments. In 1999, 80 percent of overnight shipments took place in the United States, but the market for overseas shipments was growing twice as fast. By shipping overnight through companies such as DHL and Federal Express, manufacturers could eliminate or reduce their contracts with intermediaries such as freight forwarders and have the shipments go straight through to their destinations.

Current Conditions

In early 1999, the National Customs Brokers and Forwarders Association of America (NCBFAA), petitioned the FMC to declare forwarders as shippers, thereby making them eligible to joins shippers' associations. Memberships in such associations would help to streamline the end-to-end transportation package, as well as to enhance their bargaining powers in securing competitive rates. In 2004, NCBFAA had more than 600 members.

Unlike airline passenger industries, airline freight transportation did not decline due to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, but as of 2003 air cargo still accounted for only 4 percent of international traffic and 2 percent of domestic traffic. Yet, The Journal of Commerce reported that forwarders were responsible for the origination of 90 percent of international frieght and 60 percent of domestic freight. With half of all international air cargo shipped on passenger planes, the industry can be at the mercy of global political conditions. In 2003, for example, passenger air travel—and cargo shipments by extension—to and from Asia were compromised by the outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS).

Nonetheless, freight forwarders with global skills and connections will continue to be in the greatest demand. Worldwide e-commerce sales were expected to reach $3.2 trillion by 2003, according to Forrester Research Inc. International transportation logistics experts who are knowledgeable in import duties, shipping charges, taxes, and returns processing will be worth their weight in gold. The size of the company would not be a factor in resiliency, because smaller companies were often able to meet custom, individual needs more effectively than larger companies.

Intermodal shipments by rail, on the other hand, had increased dramatically by 2003, surpassing coal to become the number one source of revenue for the rail transportation sector. The market was expected to continue to increase, as financial incentives were offered to investors in the infrastructure and the 4.3 cent fuel tax on railroads was to be eliminated.

In 2002, customs brokers were eagerly anticipating the new computer system, Automated Commercial Environment (ACE). The long delays in development and delivery were virtually erased after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and the system was pushed forward quickly as a strong line of defense. ACE was to replace the outdated Automated Commercial System (ACS) by consolidating all data for the trade. With the old ACS system, if customs brokers needed import figures, the figures had to be requested from other agencies. In addition, preliminary cargo information would be incorporated as part of the ACE system.

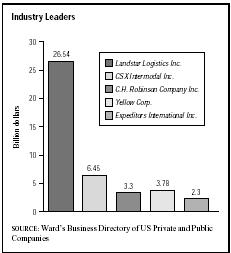

Industry Leaders

Landstar Logistics Inc. of Jacksonville, Florida, was the industry leader with $26.5 billion in 2001 revenue on the strength of just 800 employees. In distant second place was CSX Intermodal Inc., also of Jacksonville, with $6.5 billion in revenue and 10,000 employees. Third was C.H. Robinson Company Inc., of Eden Prairie, Minnesota, with $3.3 billion in revenue and 3,800 employees. Rounding out the top five were Yellow Corp. of Overland Park, Kansas, with $3.8 billion in revenue and 30,000 employees, and Seattle-based Expeditors International Inc., with $2.3 billion in revenue and 8,000 employees.

America and the World

The arrangement of freight transportation continued to develop into a global industry. Shippers found the international market to be particularly demanding because of high costs and complicated tariff schedules, rendering the services of freight forwarders and customs brokers especially valuable. Although international forwarding problems have arisen, such as an FMC sanction against Korean forwarders in 1992, most international forwarding has been negotiated without incident. Shippers in the Far East are unusually receptive to the use of transportation intermediaries.

The freight forwarding community itself attained an international perspective. An excellent example of its global character is United Shipping Associates, a band of 30 small companies from around the world that joined together in an effort to compete with the larger forwarding companies. Although the group was headquartered in Boulder, Colorado, approximately one-third of its members were non-U.S. companies. Through the association, the members developed an international network comparable to that of a large international firm.

Smaller carriers were forced to develop innovative marketing schemes to compete with large firms, while the

large firms focused on improving global networks and customer service. Although globalization, together with automation, appeared to favor the larger firms, smaller firms continued to court shippers with their strong service orientation.

Research and Technology

The U.S. Customs Department's automation initiative forced forwarders and brokers to embrace technology. All customs brokers licensed after September 1988 were required to be proficient in the Automated Broker Interface (ABI), a component of the Automated Commercial System, which is the department's system for reducing paperwork. Although this system increased the efficiency and speed of customs transactions, some firms objected to its use on the grounds that it was costly and difficult to implement. Smaller firms claimed the costs were prohibitive. Nevertheless, the Customs Department continued to promote ABI and other automated systems designed to revolutionize the customs clearing process.

In addition to the Customs Department's officially sanctioned automation directive, customers themselves demanded up-to-the-minute information that could only be provided by computer. As more businesses adopted time-based inventory management systems, the demand for flexible and responsive distribution services, as well as accurate and timely information on shipments, increased. Forwarders were forced to install computers to meet these demands.

In an effort to provide this information, many companies replaced their own computer programs with Electronic Data Interchange (EDI), a mainframe system that provided customers with online access to information on shipments. EDI allowed the freight transportation industry to meet many of the demands of shippers. One of EDI's more popular features is electronic document transmission, including electronic invoicing and remittance. Moreover, the system is well-equipped to meet the demands of just-in-time delivery by minimizing errors and reducing order cycles. The information available through EDI is, however, second hand. Freight forwarders and customs brokers must obtain the status of shipments from carriers before the information is available to customers. Many EDI users are trying to gain direct access to carrier systems in order to better serve their customers.

In addition, the new ACE system was a long-awited technological advancement for the industry. According to Country ViewsWire, ACE was the "most profound change in business practice that the industry has been anticipating since the Customs Modernization Act passed in 1993."

Further Reading

Armbruster, William. "Shipper Concern Over Airline Cutbacks." Journal of Commerce Online, 3 April 2003.

Baker, Deborah J., ed. Ward's Business Directory of US Private and Public Companies. Detroit, MI: Thomson Gale, 2003.

Coppersmith, Chris. "Airlines, Forwarders Must Work Together." The Journal of Commerce, 17 March 2003.

Dupin, Chris. "Intermodal Will Top Rail Revenue in '03: AAR." JoC Online, 20 September 2003.

Hoover's Company Fact Sheet. "Landstar System Inc." 3 March 2004. Available from http://www.hoovers.com .

National Customs Brokers and Forwarders Association of America, Inc. 22 March 2004. Available from http://www.ncbfaa.org/body/join.htm .

U.S. Census Bureau. Transportation Annual Survey. 8 March 2004. Available from http://www.census.gov .

"USA Industry: Customs Brokers Lobby Congress." Country ViewsWire, 24 September 2002.

"USA Regulations: Customs's ACE System Is Around the Corner." Country ViewsWire, 22 May 2002.

Wirsing, David. "Smaller: Lack of Size Doesn't Mean Weakness in the Turbulent Global Air Freight Shipping Market." Air Cargo World, July 2003.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: