SIC 4741

RENTAL OF RAILROAD CARS

This category includes establishments primarily engaged in renting railroad cars, whether or not also performing services connected with the use thereof, or in performing services connected with the rental of railroad cars. Establishments, such as banks and insurance companies, which purchase and lease railroad cars as investments are classified based on their primary activity.

NAICS Code(s)

532411 (Commercial Air, Rail, and Water Transportation Equipment Rental and Leasing)

488210 (Support Activities for Rail Transportation)

Industry Snapshot

Railcar leasing companies are intermediaries in the transportation industry—they do not solicit or transport freight. Rather, they support the movement of products through the services they offer. Shippers and railroads are the primary customers of railcar leasing companies. Because the anticipated usage time of railcars is relatively short, shippers and railroads tend to lease equipment in order to preserve capital and avoid the prohibitive costs of purchasing and maintaining the specialized equipment.

Rail transportation suffered a decline into the 2000s, but was improving as of 2003. New markets for rail shipments, consolidations, and fewer companies in the industry were all contributing factors in the upswing. However, by the mid-2000s, new proposed safety regulations, such as the installation of reflector tape, was expected to cost the industry millions of dollars over a 10-year period.

Organization and Structure

Leasing companies offer two basic leasing options: capital leases and operating leases. A capital lease bestows all the economic benefits and risks of the leased property on the lessee. These contracts usually cannot be canceled and the lessee is responsible for the upkeep of the equipment. Capital leases usually amortize the value of the equipment over the life of the lease. An operating lease, also called a service lease, is written for less than the life of the equipment and the lessor handles all the maintenance and service. The operating lease usually can be canceled if the equipment becomes obsolete or unnecessary. Most railcar leasing companies are either operating or capital leasing companies, though some of the larger companies have separate operations offering both types of leases.

Railcar leasing companies are further categorized by their areas of specialization. The largest lessors have the resources to offer diversified fleets, although more often than not they are best known for their expertise in a few railcar markets. The average-sized leasing company is decidedly niche-oriented. There are many types of railcars including boxcars, tank cars, and covered hoppers. These cars are designed to carry specific cargos and have different maintenance needs. Leasing companies with average-sized fleets tend to specialize in one or two specific railcar types.

Financial Structure. Several elements affect the earnings of railcar leasing companies: new car purchases; the number of cars leased (called the utilization rate and expressed as a percentage of the total fleet); and leasing rates. New cars are purchased during, or in anticipation of, strong economic periods and when tax laws favor investment. Utilization rates usually reflect the overall health of the economy. Though long-term leases sustain utilization rates during recessionary periods, it is difficult to maintain utilization rates above 90 percent during a weak economy. From 1920 through 1994, leasing rates were regulated by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC); freight car rates were subsequently determined by free-market forces.

Background and Development

The railcar renting industry emerged in the late nineteenth century in response to a growing demand for specialty freight cars. By the late 1800s, rail tracks had stretched across the nation; shippers of perishables, such as fruit, and liquids, such as oil, were anxious to take advantage of distant yet rail-accessible markets. Without refrigerator cars or liquid carrying (tank) cars, these shippers were restricted to local markets. Since the railroads were unwilling to provide these cars because of their high cost and seasonal or otherwise uneven demand, the shippers built and maintained private car fleets themselves. The larger shippers rented their cars to smaller shippers who could not afford to maintain their own fleets.

Although the early private freight car companies often were regarded as negative additions to the railroad family, these companies were essential to the development of a number of American industries. For example, midwestern meat packers who were forced to ship only during the cold winter months could operate 12 months a year when refrigerated cars were introduced. Similarly, fruit growers in California could ship perishables all the way to the east coast in refrigerated cars.

Moreover, the mobility of the private railcar fleet suited the shorter seasons of other fruit growing regions. These fleets could follow harvests around the country; peach growers in Georgia, whose crops were harvested in June, had access to refrigerated cars until the end of their summer season, at which point the growers from Michigan could rent the cars for their fall harvest. Since the railroads operated in a specific region, these short demand cycles discouraged railroads from purchasing the refrigerated cars. The private railcar fleets were more flexible than individual railroad fleets.

Although the private car industry originally focused on the short-term needs of shippers and railroads, the advent of the long-term lease enhanced the industry's strength and size. Throughout railroad history, leases were negotiated between shippers or railroads and banks; however, these leases were financing instruments. The notion of long-term leasing specialty cars was not introduced until 1902, when Max Epstein, the founder of the large lessor GATC, began leasing tank cars. The long-term lease has provided a buffer against economic slumps, allowing some companies to coast through difficult periods on the income from old leases.

The financial arrangements between private car companies and railroads were numerous and varied during the railroad boom. However, the Transportation Act of 1920 empowered the ICC to set maximum and minimum carhiring rates. Since the availability of specialty cars was vital to the health of both the shippers and the growing industrial economy, particularly because oil was transported in specialty cars, every effort was made to eliminate discriminatory pricing even before the Transportation Act was passed. Nevertheless, despite the efforts of the ICC and other regulatory agencies, discriminatory practices did exist. In fact, Standard Oil Co., which controlled the Union Tank Car Co., was repeatedly accused of manipulating the supply of tank cars to its advantage.

One particularly unpopular practice, used often by Armour Car Lines, a refrigerated car specialist, was the exclusive contract. In this arrangement, the railroads agreed to use only one private car company for all of a particular type of traffic. The car line was obligated to provide enough equipment to handle all the shipments, and to bear the icing costs associated with refrigeration. These contracts were considered discriminatory and monopolistic.

As a result of these types of practices, the industry was highly regulated for more than 70 years. However, in 1992 the ICC voted to eliminate the rate prescription policy in an effort to promote competition and efficiency. Under this deprescription plan, freight cars ordered or put into service on or after January 1, 1991, became subject to free-market rates. Car hire rates for equipment ordered or in service prior to that date were frozen at 1990 levels. The ICC voted to implement the deprescription plan gradually, beginning on January 1, 1994, with complete free market rates prevailing after December 31, 2000. This legislation represented a significant break from traditional railroad-related policy.

More than anything, the costs associated with specialty cars continued to motivate shippers and railroads to lease. In fact, in the interest of streamlining, some shippers who owned small specialty fleets chose to enter sale-leaseback agreements. By selling their cars to an operating lessor and leasing them back under an operating lease, the shipper transferred all maintenance responsibility to the lessor and shed a business that was usually cumbersome to manage and unrelated to the principal revenue-generating operation. This type of arrangement was typical of the emphasis on cost cutting and efficiency.

The 1990s brought competition from banks searching for financing activities, and weakness in the airline industry created a financial lease vacuum. The relative health of the railroad industry provided an attractive alternative for bankers looking for finance leasing opportunities. This available financing, coupled with low rates made buying railcars an attractive alternative to leasing.

One novel way for securing business was for the lessors to lease railcars themselves. For example, industry leader GATX Corp. added 6,100 new railcars to its fleet between 1997 and 1999. However, it did not purchase the railcars; it leased them from investors who put up the purchase money in return for a stake in the rent when GATX re-leases them to customers.

The 1998 domestic market was slightly depressed because of international economic slumps, particularly in the steel and grains markets. Because of the uncertainty of the market's future, railcar lessors were offering longer-term leases at low rates to accommodate the shippers and keep their business.

However, 1998 and 1999 were good years to become more competitive and upgrade the fleets. New construction of railcars was close to 70,000 units in 1998. Larger (more than 5000 cubic feet) grain cars and aluminum coal cars were two of the upgrades most in demand. By 1999, lessors owned more than 50 percent of the North American railcar fleet.

Current Conditions

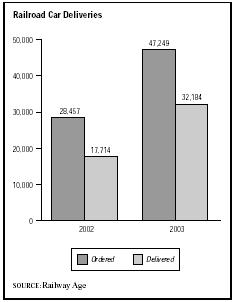

The early 2000s saw a continued decline in freight car demand. By 2002, the industry saw its worst year in a decade and a half. That year, the industry had only 17,714 freight cars delivered, down from the 74,223 cars delivered just three years prior. Regardless, the American Railway Car Institute expected an upswing in the market, with close to 40,000 new freight cars forecast to be built in 2004. In 2003, some 32,184 cars were delivered.

By 2003, intermodal rail transportation had exceeded transportation of coal as the largest segment of the industry, increasing demand for double stacked trailerand container-on-flat cars to accommodate the increased traffic.

In 2004, the Federal Railroad Administration proposed a new safety requirement that all freight cars have reflector tape installed. Although the railcar industry would have a decade to be in compliance if the requirement took effect, the price tag for tape installation was $100 per car. In addition, because the tape must be

installed in temperatures exceeding 50 degrees Fahrenheit, rail cars in the northern states would have only portions of the year to complete the installation process.

As of 2004, GE Railcar was still in the process of cleaning up a former site for railcar repair and cleaning that had been closed since 1988. The Environmental Protection Agency was working with the company to clean up contaminated ground water.

Industry Leaders

For the most part, the railcar leasing industry is a niche-oriented business comprising small to medium-sized firms that specialize in one or two specific types of railcars. However, a few giant and diversified leasing companies have dominated the industry.

By far the largest lessor is Chicago-based General Electric Railcar Services Corp., a wholly owned subsidiary of GE Capital. A merger with Itel in 1992 left GE Railcar with a fleet of 140,000 freight cars, the largest and most diversified fleet in the industry. The company also had the most extensive repair network with 11 railcar repair facilities, 9 mobile repair facilities, and 6 wheel shops in the United States and Canada. Despite the size and diversification of its fleet, GE is best known for its boxcars. The company's 2001 revenues were $1.1 billion.

In second place was TTX Company, also of Chicago. It had $586 million in 2001 revenues and 500 employees. TTX specialized in intermodal cars. In third place was GATX Financial Corp. of Chicago, with $500 million in revenues and 200 employees. GATX was the largest lessor in the specialized market of tank cars. Rounding out the top companies was fourth place Chicago Freight Care Leasing Company of Rosemont, Illinois, with $14 million in revenue and fewer than 100 employees.

Research and Technology

Since its inception, the railcar leasing industry has capitalized on the fact that specialized cars are expensive to purchase and maintain. These specialized cars were developed in response to the specific needs of shippers and railroads. As cargo became more specialized, so did the cars in which the cargo was transported, and technology and innovation continued to enhance the industry. Railcars evolved from refrigerated cars to ultra-modern designs such as GATC's Arcticar, a cryogenically cooled railcar for frozen food transport.

Oftentimes, a new railcar design created a niche market. This type of opportunity occurred when Greenbrier/Gunderson introduced the Autostack car in 1992. The development of this car addressed the surge in inter-modal traffic. The railroads, and the transportation industry overall, saw an increase in intermodalism in the 1990s. Intermodal transportation is the use of two or more modes of transportation to move cargo. Greenbrier/Gunderson's Autostack car is a technologically advanced design used to transport automobiles via sea and land. The Autostack was such a successful innovation that a separate leasing company called Autostack began operations in 1992. This new car virtually created its own market.

The 1990s, however, added a twist to the specialization effort. The search for streamlining and cost savings encouraged the development of designs that made operations more efficient. General Electric Railcar, for example, redesigned the boxcars used by paper shippers to reduce cargo damage. These changes, such as watertight seals and the elimination of protrusions inside the boxcar that could damage the cargo, reflected the emphasis on quality and efficiency in the 1990s.

Advances in railcar designs and increased confidence in rail transportation continued to bolster the industry. Despite economic factors such as low interest rates that promote buying over leasing, railcar leasing companies were optimistic. Technology and specialization continued to be the critical factors contributing to the success of the railcar leasing industry. One area of design development at the end of the decade was in grain and plastic pellet cars, now ranging in size from 5,100 cubic feet to the giant 5,300-cubic-foot covered hopper. The 286-cubic-foot, rapid-discharge aluminum coal car also was considered a good investment.

Further Reading

"About GATX Rail." 2004. Available from http://www.gatx.com/rail/about.asp .

Baker, Deborah J., ed. Ward's Business Directory of US Private and Public Companies. Detroit, MI: Thomson Gale, 2003.

Dupin, Chris. "Intermodal Will Top Rail Revenue in '03: AAR." JoC Online, 20 September 2002.

"North American Railroad Freight Car Builders Predict Improved Industry Activity in 2003 and 2004." Railway Supply Institute, 9 September 2002.

"P & R Railcar Service." 23 March 2004. Available from http://www.epa.gov/reg3wcmd/ca/md/pdf/mdd078288354.pdf .

Simpson, Thomas D. "What's the Temperature Like Around the Industry?" Railway Age, March 2004.

U.S. Census Bureau. Transportation Annual Survey. 8 March 2004. Available from http://www.census.gov .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: