SIC 4939

COMBINATION UTILITIES, NOT ELSEWHERE CLASSIFIED

This industry classification includes combination electric and natural gas utilities not categorized elsewhere.

NAICS Code(s)

221111 (Hydroelectric Power Generation)

221112 (Fossil Fuel Electric Power Generation)

221113 (Nuclear Electric Power Generation)

221119 (Other Electric Power Generation)

221122 (Electric Power Distribution)

221210 (Natural Gas Distribution)

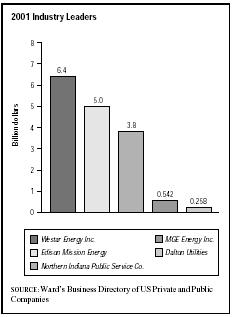

The 2001 industry leader for combination utilities not elsewhere classified was Westar Energy Inc. of Topeka, Kansas. Westar had $6.4 billion in revenue and 5,600 employees. As of 2003, the company boasted 650,000 electricity customers. Most of its facilities were coal-fired, and the company had a 5,900 mega watt generating capacity. Other notable companies in 2001 were Edison Mission Energy of Irvine, California, with almost $5.0 billion in revenue and 1,100 employees; Northern Indiana Public Service Co. of Merrillville, Indiana, with $3.8 billion in revenue and 6,000 employees; MGE Energy Inc. of Madison, Wisconsin, with $542 million in revenue and 700 employees; and Dalton Utilities of Dalton, Georgia, with $258 million in revenue and 300 employees.

By the turn of the twentieth century, there were more than 2,000 private utilities and more than 800 publicly owned utilities in the United States. About three dozen of these early companies were combined electric and gas distribution companies. This occurred at a time when municipal lighting and heating were largely produced through the generation of synthetic coal gas. When street lighting was developed, the gas producers became electric suppliers. When natural gas became available in the 1900s, the utilities continued to serve as gas suppliers as well.

In the early 1900s, state governments begun regulating electric utilities; state regulation of the venting of natural gas used in electricity production began in the late 1920s. Complaints of excessive rates charged by utilities for electric service led Congress to pass two pivotal laws in 1935: The Federal Power Act and the Public Utility Holding Company Act. The first law created a Federal Power Commission (now the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, or FERC) to oversee interstate power transactions and transactions between wholesale bulk energy suppliers. The second law reined in previous abuses linked to pyramiding holding companies in the United States. A third influential law was the Natural Gas Act of 1938, which gave FERC authority to fix pipeline rates. In 1942, the act was amended to regulate interstate sales of gas.

Historically, the same type of regulation used for electric utilities has been applied to natural gas utilities. In 1954, the Supreme Court of the United States gave FERC the authority to regulate prices all the way back to the well. The commission experimented with "area rates" that set higher rates for new gas discoveries and lower prices for "old gas," or existing production. During the late 1960s, burgeoning demand for natural gas forced gas utilities to allocate demand. In 1978, Congress stepped in again by enacting the Natural Gas Policy Act, an extremely complex law with more than 20 different categories of gas prices. By 1989, Congress gave up trying to regulate supply and demand, passing legislation to phase out price controls on most types of gas.

In 1992, FERC issued Order 636, which forced gas transmission companies to redesign rate structures, essentially changing the way local gas distribution companies obtained natural gas. That same year, Congress passed the Energy Policy Act, which increased competition within the electricity industry. In 1996, FERC issued Orders 888 and 889, final rules governing access to utility power lines. FERC also announced a new policy to consider mergers within a 15-month period.

Natural gas companies that have strong marketing capabilities have even stronger impetus to acquire or merge with electric companies in order to increase the gas companies' share of the power marketing pie. Gas marketers with the ability to also market power will buy a foothold in the electricity market through acquisitions or strategic alliances.

In the past, when gas-to-gas company mergers were proposed, they were reviewed by the Federal Trade Commission and other agencies. Electric utility mergers, however, are overseen by FERC, but even FERC doesn't know how to handle overlap between an electric company and a gas company. The agency did address electric and gas mergers in its new merger policy, issued in late 1996; these mergers were to be considered on a case-by-case basis. FERC was being cautious because a large number of mergers in an industry will reduce the number of active players in the market, raising questions of market power. Combination utilities in retail markets that were once the province of two distinct, unaffiliated gas and electric companies raised similar issues of market power and customer choice.

The governmental deregulation of the utilities industries in the 1990s was intended in part to break up monopolies and create market competition. The privatization of the industry forced more cost-effectiveness, and ultimately consumers were paying 7-15 percent less for natural gas in 1997 than they were 10 years previously. However, the utilities companies used the profits to buy out smaller competitors on the open market—something not possible when the utilities were under governmental rather than Wall Street's control.

In the latter half of the 1990s, natural gas comprised more than 50 percent of the energy market. As older nuclear power facilities and coal-burning electric utilities companies shut down, they were replaced by or converted to natural gas energy facilities. When electric utilities providers began to use natural gas for electric power generation, a new utilities super-power appeared on the horizon: instead of natural gas companies buying out their smaller natural gas competitors, they began aligning with electric utilities companies to provide multiple services to end-users. Thus, by the millennium, some of the largest utilities providers were in fact hybrid entities offering both electricity and natural gas services to their customers.

By 2002, natural gas usage still outpaced that of electricity. That year, 22.7 trillion cubic feet of natural gas was consumed, as compared with 3.8 trillion kilowatt hours of electricity. The average gas cost was $5.53 per thousand cubic feet, and the average electricity cost was 7.21 cents per kilowatt hour. Both were expected to increase about 2 percent annually into 2025. Both industry segments were expecting to pursue alternative renewable power sources into the 2000s.

Further Reading

Baker, Deborah J., ed. Ward's Business Directory of US Private and Public Companies. Detroit, MI: Thomson Gale, 2003.

Hoover's Company Fact Sheet. "Westar Energy Inc." 3 March 2004. Available from http://www.hoovers.com .

U.S. Department of Energy. Annual Energy Outlook 2004 With Projections to 2025. Available from http://www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/aeo/electricity.html ".

——. Monthly Energy Review, February 2004. Available from http://www.eia.doe.gov .

U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Economic and Employment Projections. 11 February 2004. Available from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/ecopro.toc.htm .

U.S. Department of State. United States Information Agency. Energy Restructuring in the United States. Available from http://www.usia.gov/abtusia/GE1/wwwh8003.html .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: