COMMUNICATION

Communication is the sharing or exchange of thought by oral, written, or nonverbal means. To function effectively, managers need to know and be able to apply strategically a variety of communication skills that match varying managerial tasks. These tasks might call for nonverbal, presentational, or written skills as the manager meets others, speaks at meetings, or prepares reports to be read by clients or those higher on the organizational ladder. To work effectively, managers also need to know sources of information. Finally, managers need to understand the different communication channels available.

UPWARD AND DOWNWARD

COMMUNICATION

Information, the lifeblood of any organization, needs to flow freely to be effective. Successful management requires downward communication to subordinates, upward communication to superiors, and horizontal communication to peers in other divisions. Getting a task done, perhaps through delegation, is just one aspect of the manager's job. Obtaining the resources to do that job, letting others know what is going on, and coordinating with others are also crucial skills. These skills keep the organization working, and enhance the visibility of the manager and her division, thus ensuring continued support and promotion.

Downward communication is more than passing on information to subordinates. It may involve effectively managing the tone of the message, as well as showing skill in delegation to ensure the job is done effectively by the right person. In upward communication, tone is even more crucial, as are timing, strategy, and audience adaptation. In neither case can the manager operate on automatic as the messages are sent out.

THE COMMUNICATION PROCESS

At first glance the communication process, or the steps taken to get message from one mind to another, seems simple enough. As the definition at the opening suggested, the sender has an idea, which he transmits to the receiver through signs—physical sensations capable of being perceived by another. These signs might be a printed or spoken word, a gesture, a hand-shake, or a stern look, to name just a few. The receiver takes those signs, interprets them and then reacts with feedback.

The process is more complex, though. When communicating, the sender encodes the message. That is, she chooses some tangible sign (something which can be seen, heard, felt, tasted, or smelled) to carry the message to the receiver. The receiver, in turn, decodes that message; that is, he finds meaning in it. Yet the signs used in messages have no inherent meaning; the only meaning in the message is what the sender or receiver attributes to it.

To make sense out of a message, to determine the meaning to attribute to it, the receiver uses perception. With perception, the receiver interprets the signs in a communication interaction in light of his past experience. That is, he makes sense out of the message based on what those signs meant when he encountered them in the past. A firm, quick handshake, for example, may signal "businesslike" to someone because in the past he found people who shook hands that way were businesslike.

PERCEPTION

No person sees things exactly the same way as another; each has a unique set of experiences, a unique perceptual "filter," through which he or she compares and interprets messages. Making up this filter is the unique blend of education, upbringing, and all of the life experiences of the perceiver. Even in the case of twins, the perceptual filter will vary from between them. When communicating, each receiver uses that filter to give meaning to or make sense out of the experience.

Herein lies the challenge in communication, particularly for managers who need to be understood in order to get things done: getting the receiver to comprehend the message in a way similar to what was intended. While the word "communication" implies that a common meaning is shared between sender and receiver, this is not always the case. Under optimum circumstances, the meaning attributed to the message by the receiver will be close to what was intended by the sender. In most situations, however, the meaning is only an approximation, and may even be contrary to what was intended. The challenge of communication lies in limiting this divergence of meanings between sender and receiver.

While the wide range of potential experiences make communicating with someone from within the same culture a challenge, across cultures the possibilities are even wider and the challenge even greater. What one sign means in one culture might be taken in an entirely different way in another. The friendly Tunisian businessman who holds another man's hand as they walk down the street may be misunderstood in the North American culture, for example. Similarly, an intended signal may mean nothing to someone from another culture, while an unintended one may trigger an unexpected response.

Understanding the dynamics that underlie perception is crucial to effective and successful communication. Because people make sense out of present messages based on past experiences, if those past experiences differ, the interpretations assigned may differ slightly or even radically depending on the situation. In business communication, differences in education, roles in the organization, age, or gender may lead to radical differences in the meaning attributed to a sign.

AUDIENCE ADAPTATION

The effective communicator learns early the value of audience adaptation and that many elements of the message can be shaped to suit the receiver's unique perceptual filter. Without this adaptation, the success of the message is uncertain. The language used is probably the most obvious area. If the receiver does not understand the technical vocabulary of the sender, then the latter needs to use terms common to both sender and receiver.

On the other hand, if the receiver has less education than the sender, then word choice and sentence length may need to be adapted to reflect the receiver's needs. For example, if the receiver is skeptical of technology, then someone sending a message supporting the purchase of new data processing equipment needs to shape it in a way that will overcome the perceptual blinders the receiver has to the subject. If the receiver is a superior, then the format of the message might need to be more formal.

COMMUNICATION BARRIERS

Communication barriers (often also called noise or static) complicate the communication process. A communication barrier is anything that impedes the communication process. These barriers are inevitable. While they cannot be avoided, both the sender and receiver can work to minimize them.

Interpersonal communication barriers arise within the sender or receiver. For example, if one person has biases against the topic under discussion, anything said in the conversation will be affected by that perceptual factor. Interpersonal barriers can also arise between sender and receiver. One example would be a strong emotion like anger during the interaction, which would impair both the sending and receiving of the message in a number of ways. A subtler interpersonal barrier is bypassing, in which the sender has one meaning for a term, while the receiver has another (for example, "hardware" could be taken to mean different things in an interchange).

Organizational barriers arise as a result of the interaction taking place within the larger work unit. The classic example is the serial transmission effect. As a message passes along the chain of command from one level to the next, it changes to reflect the person passing it along. By the time a message goes from bottom to top, it is not likely to be recognized by the person who initiated it.

Although communication barriers are inevitable, effective managers learn to adapt messages to counteract their impact. The seasoned manager, especially when in the role of sender, learns where they occur and how to deal with them. As receiver, she has a similar and often more challenging duty. The effort is repaid by the clearer and more effective messages that result.

COMMUNICATION REDUNDANCY

While audience adaptation is an important tool in dealing with communication barriers, it alone is not enough to minimize their impact. As a result, communication long ago evolved to develop an additional means to combat communication barriers: redundancy, the predictability built into a message that helps ensure comprehension. Every message is, to a degree, predictable or redundant, and that predictability helps overcome the uncertainty introduced by communication barriers. Effective communicators learn to build in redundancy where needed.

Communication redundancy occurs in several ways. One of the most obvious of these is through simple repetition of the message, perhaps by making a point early and again later into the same message. A long report, by contrast, might have its main points repeated in a variety of places, including the executive summary, the body, and the conclusion.

Another source of redundancy lies in the use of multiple media. Much spoken communication is repeated in the nonverbal elements of the message. A formal oral presentation is usually accompanied with slides, product samples, or videotaped segments to support the spoken word. A person interviewing for a job stresses his seriousness and sincerity with a new suit, a warm handshake, consistent eye contact, and an earnest tone in his voice.

A less obvious but more frequent source of redundancy lies in the grammar and syntax (roughly the word order used) of the message. These back up a message by helping the reader or listener predict the unknown from the known. For example, the role and meaning of an uncertain word at the beginning of a sentence can be determined partly by its placement after the word "the" and before a verb in the sentence, as well as by whether or not the verb takes the singular or plural.

In the previous example, the context in which the written message takes place, the collective meanings of the previous and following sentences, also adds to the predictability. Should noise garble one word of the message, the other words surrounding it can provide the clues needed for understanding, something that anyone familiar with speaking or reading a foreign language would know. Similarly, in a technical description, the context surrounding an unclear word or concept may be enough to determine its meaning, especially in a carefully constructed message.

A surprising source of communication redundancy lies in the way a message is formatted. In a business environment, format can help the receiver predict what will be in a message. A good example is the traditional annual report, which always carries the same type of information. Similarly, someone reading a memorandum from a colleague can reasonably expect that it will deal with internal business matters.

By contrast, the expectations inherent in a particular format can serve as a source of noise when it contains an unexpected message. For example, a company attempting to be innovative sends out its annual report as a videotape. Many of those receiving it might miss the point since it does not look like an annual report. On the other hand, since it might arouse attention, using a familiar format to package new material can be an effective marketing tool in another application.

As a result of redundancy, in whatever form it may appear, much of any message is predictable. The unpredictable element of the message, the new material that the receiver learns from the interaction, is the information that is inherent in the message. Everything else backs the message.

While managers need skill in all areas of communication, two areas, nonverbal communication and the corporate grapevine, are particularly relevant. Both are often misunderstood, and skill in strategically communicating through them is invaluable.

NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION

Nonverbal communication occurs when there is an exchange of information through nonlinguistic signs. In a spoken (and to some extent written) message, it consists of everything except the words. Nonverbal communication is a valid and rich source of information and merits close study. As with other elements of communication, the meaning of nonverbal signals depends upon perception. It does not have to be intentional in order to carry meaning to another person.

Nonverbal communication serves a variety of purposes, including sending first impressions such as a warm handshake. It also signals emotions (through tears or smiles), status (through clothing and jewelry), and when one wants to either take or relinquish a turn in conversation (using gestures or drawing a breath). Nonverbal signals can also signal when someone is lying; for example when being deceptive, vocal pitch often rises.

Many think of "body language" as synonymous with nonverbal communication. Body language is a rich source of information in interpersonal communication. The gestures that an interviewee uses can emphasize or contradict what he is saying. Similarly, his posture and eye contact can indicate respect and careful attention. Far subtler, but equally important, are the physical elements over which he has little control, but which still impact the impression he is making on the interviewer. His height, weight, physical attractiveness, and even his race are all sources of potential signals that may affect the impression he is making.

But nonverbal signals come from many other sources, one of which is time. If the interviewee in the previous example arrived ten minutes late, he may have made such a poor impression that his chances for hire are jeopardized. A second interviewee who arrives ten minutes early signals eagerness and promptness.

Haptics is a source of nonverbal communication that deals with touch. An interviewee with a weak hand-shake may leave a poor impression. The pat on the back that accompanies a verbal "well done" and a written commendation may strongly reinforce the verbal and written statements. Subconsciously, most managers realize that when the permissible level of haptic communication is exceeded, it is done to communicate a message about the state of the parties' relationship. It is either warmer than it had been, or one of the parties wishes it so. Unfortunately, explain Borisoff and Victor, conflict can arise when the two parties involved do not agree on an acceptable haptic level for the relationship.

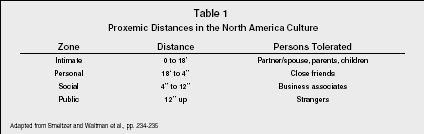

Nonverbal communication also includes proxemics, a person's relationship to others in physical space. Most are familiar with the idea of a personal space "bubble" that we like to keep around ourselves. In the North American culture, this intimate space may be an 18-inch circle around the person, which only those closest are allowed to invade. Just beyond this space close friends may be tolerated, and acquaintances even farther out. Other cultures may have wider or narrower circles. Table 1 sets out the meanings typically attributed to personal spaces in the North American culture.

Managers also send nonverbal signals through their work environment. These signals can affect the communication process in obvious or subtle ways. For example, a manager may arrange the office so that she speaks to subordinates across a broad expanse of desk. Or, she may choose to be less intimidating and use a round table for conferences. The artifacts she uses in the office may say something about who the manager is, or how she wishes to be seen. The organization also speaks through the space it allots to employees. For example, the perception that a large, windowed, corner office may signal prestige while a tiny, sterile cubicle may convey (intentionally or unintentionally) low status.

Proxemic Distances in the North America Culture

| Zone | Distance | Persons Tolerated |

| Intimate | 0 to 18′ | Partner/spouse, parents, children |

| Personal | 18′ to 4″ | Close friends |

| Social | 4″ to 12″ | Business associates |

| Public | 12″ up | Strangers |

THE GRAPEVINE

The grapevine is the informal, confidential communication network that quickly develops within any organization to supplement the formal channels. The structure of the grapevine is amorphous; it follows relationship and networking patterns within and outside the organization, rather than the formal, rational ones imposed by the organization's hierarchy. Thus, members of a carpool, or people gathering around the water cooler or in the cafeteria, may be from different divisions of a company, but share information to pass the time. The information may even pass out of the organization at one level and come back in at another as people go from one network to another. For example, a member of a civic group might casually (and confidentially) pass on interesting information to a friend at a club, who later meets a subordinate of the first speaker at a weekend barbecue.

The grapevine has several functions in the organization. For one, it carries information inappropriate for formal media. Fearing legal repercussions, most would rarely use printed media to share opinions on the competence, ethics, or behavior of others. At the same time, they will freely discuss these informally on the grapevine. Similarly, the grapevine will carry good or bad news affecting the organization far more quickly than formal media can.

The grapevine can also serve as a medium for translating what top management says into meaningful terms. For example, a new and seemingly liberal policy on casual dress may be translated as it moves along the grapevine to clarify what the limits of casual dress actually are. As it informally fleshes out or clarifies what is also traveling in the formal channels, the grapevine can also serve as a source of communication redundancy. And when these corporate-sanctioned channels are inaccurate, especially in an unhealthy communication climate, what is on the grapevine is usually trusted far more by those using it than what passes on the formal channels.

Participants in the grapevine play at least one of several roles. The first of these, the liaison, is the most active participant since he both sends and receives information on the grapevine. This person often has a job with easy access to information at different levels of the organization (and often with little commitment to any level). This might be a secretary, a mailroom clerk, a custodian, or a computer technician. Often, too, the liaison is an extrovert and likable. While this role means that the liaison is in on much of what is going on in the organization, he also takes a chance since the information he passes on might be linked back to him.

Another role played in the grapevine is the deadender. This person generally receives information, but rarely passes it on. By far the most common participant in the grapevine, this person may have access to information from one or more liaisons. This role is the safest one to play in the grapevine since the deadender is not linked to the information as it moves through the organization. Many managers wisely play this role since it provides useful information on what is happening within the organization without the additional risk passing it on to others might entail.

The third role is the isolate. For one or more reasons, she neither sends nor receives information. Physical separation may account for the role in a few instances (the classic example is the lighthouse keeper), but the isolation may also be due to frequent travel that keeps the individual away from the main office. Frequently, the isolation can be traced to interpersonal problems or to indifference to what is happening in the organization (many plateaued employees fit in this category). Not surprisingly, top management often plays the role of isolate, although often unwillingly or unknowingly. This isolation may be owing to the kinds of information passing on the grapevine or to the lack of access others have to top management.

Of course, what is passing on the grapevine may affect a person's behavior or role played. The isolate who is close to retirement and indifferent to much of what is going on around him may suddenly become a liaison when rumors of an early retirement package or a cut in health benefits circulate. Meanwhile, the youngest members of the organization may not give a passing thought to this seemingly irrelevant information.

COMMUNICATION CHANNELS

Communication channels—or the media through which messages are sent—can have an influence on the success of communication. Typical channels used in business communication are face-to-face conversations, telephone conversations, formal letters, memos, or e-mails. Each channel has its own advantages and disadvantages in communicating a particular message.

Media richness theory indicates that the various communication channels differ in their capability to provide rich information. Face-to-face interaction is highest in media richness, because a person can perceive verbal and nonverbal communication, including posture, gestures, tone of voice, and eye contact, which can aid the perceiver in understanding the message being sent. Letters and e-mails have fairly low media richness; they provide more opportunity for the perceiver to misunderstand the sender's intent. Thus, messages should be communicated through channels that provide sufficient levels of media richness for their purpose. For instance, when managers give negative feedback to employees, discipline them, or fire them, it should be done in person. However, disseminating routine, nonsensitive information is properly done through memos or e-mails, where media richness is not critical.

A communication channel that has grown in popularity in business is electronic mail, or e-mail. E-mail provides almost instantaneous communication around the world, and is often a quick, convenient way to communicate with others. This is particularly true for workers in remote locations, such as telecommuters. E-mail may also allow individuals to get their work done more quickly and to manage communication more effectively, particularly by having a record of previous correspondence easily at hand on their computer.

Despite e-mail's many advantages, there are several problems associated with the increased use of e-mail in business. First, e-mail may not be private; e-mail messages may be accessed by people who were not intended to see the messages, and this may create problems related to keeping trade secrets or managing employee relations. Additionally, e-mail messages may be accessed long after they are sent; they may leave a "paper trail" that an organization would rather not have. A second problem with e-mail use is information overload. Because e-mail is easy and quick, many employees find that they have problems managing their e-mail communication or that their work is constantly interrupted by e-mail arrival. The third problem associated with e-mail is that it reduces the benefits that occur with more media-rich communication. Much of the socialization and dissemination of organizational culture that may occur through personal interactions may be lost with the increased reliance on electronic communication channels.

John L. Waltman

Revised by Marcia Simmering

FURTHER READING:

Athos, A.G., and R.C. Coffey. "Time, Space and Things." In Behavior in Organizations: A Multidimensional View. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1975.

Borisoff, Deborah, and David A. Victor. Conflict Management: A Communication Skills Approach. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1989.

Knapp, Mark L., and Judith A. Hall. Nonverbal Communication In Human Interaction. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing, 2001.

Smeltzer, Larry R., and John L. Waltman, et al. Managerial Communication: A Strategic Approach. Needham, MA: Ginn Press, 1991.

Timm, Paul R., and Kristen Bell DeTienne. Managerial Communication. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc., 1991.

How do specific varieties of negative messages adapt the basic pattern?

Can someone help me with this please.