PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Project management is the application of relevant logic and tools to planning, directing, and controlling a temporary endeavor. While some organizations specialize in projects, others may require project management skills only occasionally to effect a change, either physical or sociological in nature, from the norm.

BACKGROUND

The origin of project management is in the construction industry, going back as far as the construction of the pyramids. A pharaoh "contracted" for the construction of his personal resting place, assigned to a project manager. This manager was responsible for the logical development of the physical structure, including quarrying and transport of stone, marshalling of labor, and construction of the pyramid as envisioned by the monarch.

Today, directives come from corporations and municipal agencies, from prospective home-owners and nonprofit organizations. Modern construction firms employ an updated model of project management, using visual tools and software to help manage the sequencing of materials delivery, equipment usage, and labor specialization. Frequently, a single firm will have multiple projects under way at a given time, complicating the need for precise timing of resource availability to complete each task effectively and efficiently.

Some professionals have recognized a similarity to construction firms in operational style. For example, legal and public accounting firms, while not requiring steel beams or earth-moving equipment, have multiple legal cases or professional audits in progress simultaneously. For these firms, it is necessary to allocate the availability of professional specialists.

Almost all companies encounter the need for project management at some point. The need may arise for a new physical plant, an expansion, or a move to a new location. Reengineering may suggest a change in processes, with an accompanying equipment rearrangement and retraining to ensure the effectiveness of the change. The speed at which technology changes, forces companies to adopt new hardware and software to stay current. Softer issues, such as the implementation of quality programs, also are within the project management purview.

NATURE OF A PROJECT

A project is typically defined as a set of interrelated activities having a specific beginning and ending, and leading to a specific objective. Probably the most important concept in this definition is that a project is intended as a temporary endeavor, unlike ongoing, steady state operations. Secondary is the uniqueness of the output.

To ensure that a project is temporary, it is necessary to define the ending explicitly. The outputs of the project, or deliverables, may be tangible (a new heating system) or intangible (a retrained workgroup), but in either case should be defined in measurable terms (completed installation or documented level of expertise). While the reason for undertaking the project may have been to reduce utility costs by 10 percent or to increase productivity by 20 percent, achieving such goals may be outside the scope of the project.

Each project requires specific definition of its goals. In a training project example, the project manager may be given responsibility for identifying and implementing a training system that will enhance productivity by 15 percent; in this case, the project is not complete until the 15 percent goal is reached. If the initial training program enhances productivity by only 12 percent, the project manager is obligated to provide additional training, or the project may be terminated as a failure. Note that a 12 percent increase in productivity was something to celebrate, but did not meet the

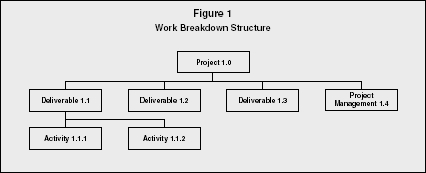

Work Breakdown Structure

Obviously, it behooves the project manager to have a well-defined scope for the project. The more nebulous the assignment, the more the project is subject to "scope-creep," or the tendency for the project to acquire additional duties. A "statement of work" document or charter, outlining the relevant specifications of deliverables, helps to keep a project clearly defined. Once the work is completely specified, the requisite activities can be identified and assigned.

The work breakdown structure (WBS) is one of the tools used by project managers to ensure that all activities have been included in planning. By numbering the project "1.0." the implication is that this is the first project for the company; subsequent projects would be numbered sequentially. In the illustrated example, the deliverables are specified on the second layer of the WBS, along with an overhead allocation for the project management team. Under each deliverable is an increasingly specified description of the activities involved in achieving the deliverable. Alternatively, the second line may be functional headings (finance, marketing, operations) or time periods (January, February, March). The objective of the WBS is to clarify that all activities have been addressed and assigned.

While the definition of a project also tends to include the word unique, this may be true only in a narrowly defined sense. A company that builds a new branch location (first project) has a template for the construction of a second branch location (second project). In the marketing field, subsequent product rollouts can learn from the initial product introduction. To the extent that the project is repetitive, the planning process, WBS, and cost estimates can provide a valuable template for future projects.

Project Performance Measures

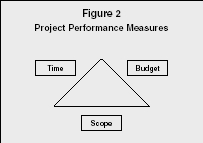

PROJECT PERFORMANCE MEASURES

The traditional measures for judging project success are: the fulfillment of scope, time and within budget. This is frequently depicted as a triangle.

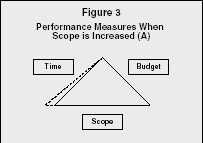

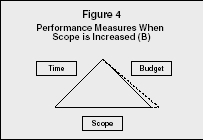

Increasing any of the triangle's sides inherently changes at least one of the other sides. Thus, increasing the scope of the project will necessarily increase either the time required to complete the project or the budget allocated to the project. Unfortunately, the expanded scope can cause both time and budget to escalate simultaneously, as constrained resources come into conflict. Some project contracts have penalty clauses that elicit hefty payments if the project completion is past the contract date. Similarly, when the scope is decreased, the requisite time and budget may be reduced; resources may be assigned elsewhere.

Performance Measures When Scope is Increased (A)

The triangle analogy breaks down when the time factor is reduced, i.e., the project completion date is moved up. An unexpected deadline change may necessitate the use of overtime resources. Overtime hours strain the budget, and may still be insufficient to complete the project within the specified time. Managers attempting to respond to deadline changes should note the relative costs of time-intensive expenses (such as weekly rental of equipment) and of resource-intensive expenses (wages).

The schedule and budget are developed subsequent to the work breakdown structure, so that all activities and resources are identified. Scheduling requires that the project manager recognize two primary aspects of project activities. First, some activities must be done in sequence, while others may be done at the same time. Second, activities that could be run in parallel with multiple resources must be performed sequentially if the same limited resources are required for both activities. Gantt charts provide time-line displays, while network diagrams, such as Program Evaluation and Review Technique (PERT) or CPM diagrams, illustrate the sequentially dependency of activities. A baseline overview of the project is developed at this point for later comparison to actual progress.

From the beginning to the ending of the project, there is a critical path, or longest time-line path through the sequenced activities. This critical path determines the minimum time required for the project, and is the focus of the project manager's attention. If any of these activities are delayed, the on-time delivery of the project is at risk. To track this risk, mile-stones are established; the project review process addresses the actual progress as compared to the scheduled progress.

The budget is typically developed by estimating expenses at the bottom layer of the WBS, then rolling up the expenses to a project total. The numbering system in the WBS can be tailored to form a chart of accounts for tracking expenses associated with each activity. The project management heading is appropriate under any of these alternatives to ensure that staff salaries/wages are suitably allocated to the project. Earned value analysis incorporates both on-time and within-budget concepts of tracking the costs incurred to date on a project.

While customer satisfaction is sometimes added as a fourth factor in the list of project performance measures, this complicates the evaluation. If the project manager brings in the project according to scope specifications, on time, within budget, then customer dissatisfaction may be due to the customer's inability to define the scope in terms that would achieve the objective. Customer service in the project management context should include adequate discussion of alternative outcomes at the scope development stage.

ROLES IN THE PROJECT

MANAGEMENT ENVIRONMENT

Who is the customer of a project? Generically, the customer is the entity to which the deliverables are actually delivered. In an externally contracted project, the customer is easily identified. In an in-house project, the customer is the executive authorizing both the initiation of the project and the money allocated to it. In either case, the customer is the one with the right to complain when the performance measures of scope, time, and budget are not met.

Ideally, a project will have a sponsor, an intermediary between the customer and the project manager. This individual can help to define the scope for optimal delivery of results, to allocate appropriate funding, to resolve conflicts during the execution of the project.

The project champion is the source of the idea for the project. While the champion is frequently an individual, the idea may originate with the board of directors or the safety committee in a company. The project champion, however, may not be the ideal choice for project manager.

The project manager is in charge of the work to be accomplished. This is not to say that the manager actually does the work, but rather that he/she is the coordinator of all relevant activities through delegation. In many cases, this manager may not possess expertise in the field, but rather possesses the skills to oversee a large number of diverse tasks and to identify the best-qualified employees to carry out the tasks. The manager should exercise judgment in assigning tasks; seasoned professionals will expect to accomplish the tasks according to their knowledge and experience, while others may require much definition and direction. In some cases, the project manager's ability to accomplish the job depends on negotiating and persuasive skills.

The authority of the project manager depends heavily on the organizational structure. In the "projectized" organization, resources are assigned exclusively to the project, then returned to a pool and assigned to a new project. The manager has near absolute authority and responsibility. In the functional organization (finance, marketing, operations, etc.), the project manager must negotiate with the functional manager for resources obtained from the department. Individuals tend to feel a greater responsibility to the functional manager. In this organization, the project manager has responsibility for the project, but relatively little authority without interference by the sponsor. The matrix organization is a managerial attempt to compromise these extremes by transferring some extent of authority from the functional manager to the project manager; thus, there are both strong-form and weak-form matrix organizations.

The project manager should be a master of many skills. Organization, negotiation, and teambuilding are desirable, while technical expertise may be less important. An expert whose intense focus on technical detail excludes the broader aspects of the project can undermine projects. Communication skills are of prime importance, as written and oral reports are mandatory. In addition, clarity of the initial assignment can reduce the amount of conflict management required in later stages of the project.

Surrounding the project manager is a team with the goal of supporting the planning, directing, and controlling functions. Typically, a full-time (or nearly full-time) team member is assigned responsibility for traditional office functions, such as communication coordination. This member may also be in charge of fielding reports and recording the responses for comparison to the baseline schedule. Other members exercise delegated authority in project oversight, up to and including direct responsibility for sub-projects within the larger project context.

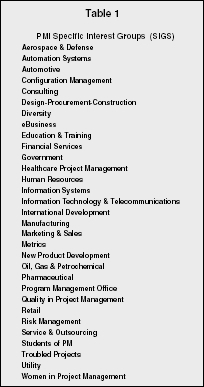

PROJECT MANAGEMENT INSTITUTE

The primary professional organization in this field is the Project Management Institute (PMI). Founded in 1969, PMI has more than 40,000 worldwide members including representatives of government, industry, and academia. This body publishes standards for the profession of project management and awards certification as a Project Management Professional (PMP) on the basis of examination; continuing certification is dependent on continuing education and service to the field of project management.

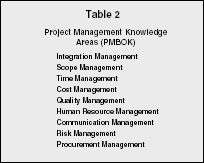

The Standards Committee of PMI has continually updated versions of the generically worded Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge

Performance Measures When Scope is Increased (B)

These knowledge areas cover the obvious concerns of scope, time, cost, and quality, conforming to

PMI Specific Interest Groups (SIGS)

| Aerospace & Defense |

| Automation Systems |

| Automotive |

| Configuration Management |

| Consulting |

| Design-Procurement-Construction |

| Diversity |

| eBusiness |

| Education & Training |

| Financial Services |

| Government |

| Healthcare Project Management |

| Human Resources |

| Information Systems |

| Information Technology & Telecommunications |

| International Development |

| Manufacturing |

| Marketing & Sales |

| Metrics |

| New Product Development |

| Oil, Gas & Petrochemical |

| Pharmaceutical |

| Program Management Office |

| Quality in Project Management |

| Retail |

| Risk Management |

| Service & Outsourcing |

| Students of PM |

| Troubled Projects |

| Utility |

| Women in Project Management |

Project Management Knowledge

Areas (PMBOK)

| Integration Management |

| Scope Management |

| Time Management |

| Cost Management |

| Quality Management |

| Human Resource Management |

| Communication Management |

| Risk Management |

| Procurement Management |

the performance measures applied to projects. In addition, the softer issues of communication and human resource management are addressed; procurement management is included, as this concept is of major importance to many of the industries involved. Of particular note, however, are the areas of project integration and risk management.

PROJECT INTEGRATION MANAGEMENT

Management of project integration includes the process of synthesis and response to change. The over-all project employs five basic processes: initiating, planning, executing, controlling, and closing.

The initiating process incorporates development of the idea for the project and justification based on a feasibility study. It is at this stage that the boundaries of the project should be defined. To return to the earlier training example, the responsibility for identifying a specific training program should be determined.

Project planning addresses the specific timeframe and budget for the project. Activities are identified and assigned. Planning is considered a most important process because without excellent planning the ensuing activities are unlikely to succeed. Executing involves carrying out the assigned activities, while controlling monitors the activity for scope, time, and budget concerns.

Perhaps the most ignored process of projects in general is the closing process. Toward the end of a project, enthusiasm can wane, and it is the responsibility of the project manager to maintain active collaboration until the end of the project. Phased-out employees should be evaluated and returned to the pool/function from which they were recruited. A series of meetings should be held to review the degree to which the performance measures were met, from both the defined scope and the satisfaction of the customer. If these are not in agreement, then the reasons should be documented. Areas of success and failure are both important to note, as these can be the basis for company-wide learning. Even dissimilar projects can provide some learning opportunities, as the company understands, for instance, its tendency to underestimate costs or scheduling requirements.

While these processes, initiating through closing, appear to be linear in nature, they instead define a feedback system. The specifics of the Planning process may indicate that the initiating idea was flawed. Execution may encounter problems with planning. controlling may indicate a return to planning, or even to the earlier initiating idea process. And closing may determine that the entire project was doomed from the outset. Failure to recognize the iterative nature of these processes can be costly, as a project may be adjusted or abandoned at early stages to prevent loss.

Within the company, the project life-cycle stages of the project should be identified. Generically, these may be identified as definition, design, test, implementation, and retirement stages, or some variation on this theme. Interestingly, each of these stages employs each of the processes described above. For example, in the definition life-cycle stage, there is an initiation process, progressing to a feasibility study. As the definition stage reaches its conclusion, it "delivers" the project to the design stage, but only if the mini-project of definition has been successful. Many projects have lingered when a rational analysis would suggest that revision or abandonment would be less costly. The iterative nature of project management logic suggests a stringent review at frequent stages to ensure that both the project itself and the environment to which the project was to respond are in agreement. Management of the integration of project stages is especially important in a rapidly changing environment.

PROJECT RISK MANAGEMENT

Among the project management knowledge areas, risk management is likely the activity that best defines project management. This umbrella concept addresses the risks in all aspects of managing a project.

First are the traditional performance measures. Was the scope well defined? If the customer assumed that a specific aspect was included, then the contracting firm's reputation may be damaged when the aspect was not specified in the charter. Were the costs estimated correctly? Underestimating can undermine profits, while overestimating can lose an opportunity for business or in-house improvement. Were the time estimates reasonable? Past-due penalties can be significant.

Other risks can include the insolvency of the customer and/or a subcontractor, or the lack of in-house expertise to accomplish the tasks involved in the project. Weather, economic changes, and governmental regulations can change the feasibility of any project. Above all is the risk that the project is not sufficient to respond to changes in the environmental circumstances that triggered the project's initiation, especially in a project of long duration.

Project management is a structured approach to solving a problem with a temporary, unique solution. Project planning is a most important stage, setting the stage on which the rest of the project must play out. The project manager should be heavily involved in this planning process to ensure his/her understanding of scope, time, and cost, the primary performance measures by which project success is measured. Monitoring of the activities enhances the probability that the project will stay on track for all of these measures. Each stage and process of project management should address the minimization of risk to the firm, in terms of both money and reputation.

SEE ALSO: Product-Process Matrix ; Program Evaluation and Review Technique and Critical Path Method ; Program Evaluation and Review Technique and Critical Path Method

Karen L. Brown

Revised by Wendy H. Mason

FURTHER READING:

Gido, Jack, and James P. Clements. Successful Project Management. Cincinnati: South-Western College Publishing, 1999.

Kerzner, Harold. Project Management: A Systems Approach to Planning, Scheduling, and Controlling. 8th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2003.

Martin, Paula. The Project Management Memory Jogger: A Pocket Guide for Project Teams (Growth Opportunity Alliance of Lawrence). Salem, NH: GOAL/QPC, 1997.

Meredith, Jack R., and Samuel J. Mantel, Jr. Project Management: A Managerial Approach. 5th ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2002.

PMI Standards Committee. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide). 2000 ed. Upper Darby, PA: Project Management Institute, 2000.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: