Retail Business Incubator

BUSINESS PLAN ACME INCUBATORS

163 Perkins Street

Jackson, Michigan 49204

Business incubation programs have become essential economic development tools for communities that are trying to improve their economies and keep them healthy over the long run. The programs—which house very-early stage companies and provide them with a full array of business planning, management, and financial services—yield excellent returns. According to research, a high percentage (84%) of the companies that "graduate" from incubation programs remain in their communities, and an average 87 percent of incubator graduates are still in business.

- EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- APPENDIX

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Need

The number of businesses being started in the U.S. has more than doubled during the past decade, with well over 520,000 new business incorporations during the first nine months of 1988 alone. But the percentage of those that survive has remained the same (according to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology) or declined (according to Dun & Bradstreet). Either way, business start-ups are facing tough odds nationwide. According to the Federal Small Business Administration (SBA), 80 percent of all new small firms opened in 1988 will fail by 1993—out of money or energy or both.

Is there any way for entrepreneurs to combat these statistics? One increasingly popular economic support tool is the business incubator which, as the name implies, is a place designed to foster the growth of small companies.

Business incubation programs have become essential economic development tools for communities that are trying to improve their economies and keep them healthy over the long run. The programs—which house very-early stage companies and provide them with a full array of business planning, management, and financial services—yield excellent returns. According to research, a high percentage (84%) of the companies that "graduate" from incubation programs remain in their communities, and an average 87 percent of incubator graduates are still in business.

A retail business incubator located in Jackson is needed and will be the ideal project to stimulate and promote community and organization partnerships, along with economic growth. It can accomplish this by providing the opportunity for job placement, on-the-job training, entrepreneurial training, business development and technical assistance, career counseling, small business financing, space for business start-ups, space for existing business owners, and space for community organizations. This retail incubator could also satisfy the one-stop-shop needs of the community.

Purpose

A retail incubator's main purpose would be to catalyze the process of starting and growing retail business. A proven model, it will provide entrepreneurs with the expertise, networks, and tools they need to make their ventures successful. This retail incubation program will diversify economies, commercialize technologies, create jobs, and build wealth. It will also shield new businesses from the harsh environment they face during the first few years of existence—the most critical period.

While the Jackson retail incubator won't work magic, it can provide an encouraging place for young companies to make their start. Oscar Wright, California's Small Business Advocate, is coordinating with numerous public and private entities to encourage and assist in the creating of incubators in the state. Mr. Wright comments: "Incubators are on the cutting edge of developing new and strategic tools for small business success and local economic diversity. Incubators afford each community an opportunity to address specific concerns germane to their own economic reality." Even though we currently have a business incubator in Jackson, it has been proven that no two incubators will be exactly alike, reflecting differing and divergent needs.

Highly adaptable, incubators have differing goals: to diversify rural economies, to provide employment for and increase the wealth of depressed inner cities, and to transfer technology from universities and major corporations.

Industry

For National Business Incubator Association's (NBIA) 1998 State of the Business Incubation Industry , surveys were mailed to all incubators in North America. Responses represented 67 percent of the 587 business incubation programs identified in NBIA's database as of spring 1998.

Researchers discovered the following:

- North American incubators have created nearly 19,000 companies still in business and more than 245,000 jobs

- Most incubator facilities (75%) are less than 40,000 square feet (the average is 36,657 square feet; median is 16,000 square feet)

- Incubators overall each served an average of 20 entrepreneurial firms in 1997 (the median number reported was 12)

- NBIA member incubators served, on average, twice as many client companies and nearly twice as many graduates as nonmember incubators

- Client companies in member incubators created, on average, one third more jobs than client companies of nonmember incubators

Primary Sponsors of Incubators

Nonprofit, Public, or Private

51 percent of all North American facilities, these incubators are sponsored by government and nonprofit organizations, and are primarily for economic development. This mission includes job creation, economic diversification, and/or expansion of the tax base.

Academic-Related

27 percent of all North American facilities, these incubators are affiliated with universities and colleges and share some of the same objectives of public and private incubators. In addition, they provide faculty with research opportunities, and alumni, faculty, and associated groups with start-up business opportunities. (This percentage includes some of the Hybrid responses that noted universities, community colleges or technical colleges.)

Hybrid

16 percent of all North American facilities, these incubators are joint efforts among government, nonprofit agencies, and/or private developers. These partnerships may offer the incubator access to government funding and resources, and private sector expertise and financing.

Private, for Profit

8 percent of all North American facilities, these incubators are run by investment groups or by real estate development partnerships. Their primary interests are economic reward for investment in tenant firms, new technology applications, and other technological transfers, and added value through development of commercial and industrial real estate.

Other

5 percent of all North American facilities, these incubators are sponsored by a variety of non-conventional sources such as art organizations, Native American, church groups, chambers of commerce, port districts, etc.

Incubator Focus

- 43%—Mixed Use

- 25%—Technology (general)

- 10%—Manufacturing

- 9%—Targeted

- 6%—Service

- 5%—Empowerment

- 2%—Other

The 1998 State of the Business Incubation Industry contains 67 charts and graphs profiling the industry and highlighting results. Some findings:

- Forty-five (45) percent of today's incubators are urban, 36 percent are rural, and the remaining 19 percent are suburban.

- Most (43 percent) are mixed use and another 25 percent are technology. Ten (10) percent focus on manufacturing companies and 6 percent on service companies. The study revealed growth of the newer, "targeted" incubators—ones that focus on a specific industry such as software, food manufacturing, multimedia, or the arts. They are 9 percent of the total.

- The average incubator was established in 1991.

- The average operating expenses are between $72,320 and $207,500.

- There is no such thing as a standard size for incubators. The average incubator is 36,657 square feet, the mean is 16,000 square feet and the range is from 600 to 500,000 square feet. (These numbers exclude space rented to tenants not receiving incubation services.)

- Eighty-five (85) percent of all senior incubator managers have a college degree or post-graduate education.

- The average incubator offers full incubation services to 20 in-house and affiliate companies; member incubators serve an average of 24.

A relatively new concept in economic development circles, business incubation has grown markedly—from 12 North American programs in 1980 to the 587 identified by this study.

The 1998 State of the Business Incubation Industry joins "The Impact of Incubator Investments" study (conducted in 1997 by Ohio University, the Southern Technology Council, University of Michigan and NBIA to paint a picture of today's incubators and the effect they're having. There's no question they are viable economic development tools. Through research we now know incubators are better at what they do if their managers remain involved through membership in the association, the industry's best professional development resource.

Economic Impact

The results of the largest study ever conducted on business incubation show that these support programs for entrepreneurial firms have impressive, measurable impacts on the companies they serve. In addition, experts are calling business incubators a "best value" in economic development, based on low program costs and high return on investment to communities.

"Business incubation programs treat entrepreneurial companies as important community and national resources, and they provide assistance that ensures company success. This study should convince communities that if they don't already have a business incubation program, they'll want to start thinking about one," says Dinah Adkins, executive director of the NBIA, Athens, Ohio.

The study, completed in October 1997, was conducted by the University of Michigan, NBIA, Ohio University and the Southern Technology Council under a grant from the U.S. Department of Commerce Economic Development Administration. It examined the impacts of business incubators, which house very-early stage companies and provide on-site management and a full array of business planning, management, and financial services. Entrepreneurial companies stay in an incubator for an average of two to three years, then graduate to become free standing.

Some of the most important results of the study—which enlisted incubator companies, graduates, managers, and stakeholders—show how effective business incubators are:

- Retail incubator companies experience very healthy growth. The average firm's sales increased by more than 400 percent from the time it entered until the time it left the incubator. In addition, the average annual growth in sales per firm in all types of incubators was $239,535.

- Business incubation programs produce graduate firms with high survival rates. A reported 87 percent of incubated companies that fulfilled program graduation requirements are still in business.

- Business incubation programs create new jobs for a low subsidy cost and a good return on investment. The estimated cost per job created in relation to public grants was $1,109. It's not uncommon for the cost per job of other job-generating economic development programs to be three to six times higher.

- Most firms that graduate from business incubators—an average of 84 percent—remain in their communities.

- Business incubation programs assist companies that create many new jobs. In 1996 incubators reported, on average, that their firms had created 468 jobs directly and 234 additional "spin-off" jobs in the community for a total of 702 jobs.

- Despite their early stage, most incubator firms provide employee benefits.

- Retail incubators contribute to their client companies' success and expand community resources, increasing early-stage capital, access to entrepreneurship education, and other sources of help to young companies.

- Retail incubation programs improve local community image.

Earlier studies and surveys had suggested that business incubation was a successful economic development strategy. "The anecdotal information said the same thing, but there had been no large-scale, national study of the industry to confirm that," says research team member Larry Molnar, director, EDA University Center for Economic Diversification, University of Michigan Business School, Ann Arbor.

"Incubation is highly adaptable, which is another reason it's such a good economic development tool," Adkins says.

The research analysis also led investigators to formulate policy recommendations. They urge incubation program sponsors at all levels to, among other things: (1) invest more heavily in incubators as a major tool in economic development, (2) target their investments to the best program type for their community resources and (3) seek evidence that any program they support adheres to the authentic definition of an incubator and strives to institute best practices. They also charged the business incubation industry with developing standard impact measures and distributing to incubators a simple toolkit, developed by the researchers, that will make data collection easy at the local level.

"Adding these measures to incubators' total evaluation process will help them track their growth and effectiveness. It will also allow the industry to create a national database, making it possible to study and improve the business incubation process in years to come," says team member Hugh Sherman, assistant professor of policy and strategy, management systems department, Ohio University in Athens.

Incubator's Delivery

There is no single formula for retail incubators. In general, however, they are defined as physical facilities that provide new firms with the supportive network necessary to increase their probability of survival during the crucial early years when they are most vulnerable. Most start-ups are short of everything but the founder's energy, and a Jackson retail incubator is one way of building on that spirit while cushioning the demands on things formative businesses don't have—particularly working capital.

Industry leaders pinpoint three areas in which a facility should "deliver" in order to rightfully be called an incubator:

- The facility should provide flexible space for a number of companies at a rent that is either below average for the area, or an exceptional value for the services provided. There should be plenty of room for each business to expand.

- Shared equipment and services are provided that would otherwise be unavailable or unaffordable to help businesses cut costs. Receptionist, photocopying and conference rooms are most popular, with security, phone answering/message center, computer access, word processing, typing, audiovisual equipment and shipping/receiving also in high demand.

- The incubator should offer experienced management advice and access to professional expertise, backed by a policy which ensures that each participating business completes a thorough business plan and any other strategic planning necessary.

Most incubators with a success rate of over 80 percent also meet a fourth criteria: access to capital. Facilities with in-house funding are often difficult to get into because they evaluate businesses more strictly, but knowing that funding is available when needed helps both the individual business and the incubator management to prosper.

Incubator Characteristics

Incubators come in different forms. According to NBIA statistics, most (47 percent) are nonprofit, operated by groups ranging from community development organizations to municipal governments seeking to create new jobs and increase local tax bases. Academic related incubators (14 percent) serve as a link between innovations developed by universities or colleges and the businesses that market them to the general public. The so-called "mixed" incubator or "hybrid," which links private companies and public institutions in an effort to create new business, comprises 14 percent.

A growing number (25 percent) are for-profit incubators, which make money by acquiring part ownership in their tenant companies or from rental payments. For-profit operations are expected to grow to at least half the total of all incubators in the next few years. The future is private, for-profit incubators. Of that there is little doubt, the only uncertainty is timing (The NBIA's Adkins, however, contends that nonprofit incubators are still growing at an extremely rapid rate—faster than for-profits—and will continue to be a strong component of the overall mix).

While the major goal of for-profit incubators is to make money—they are in the business of helping young companies because it pays—their motivation is not dissimilar to that of their tenants. Says the owner of one: "Why are we for-profit? Because like the people in the incubator, we're entrepreneurs, too. It sets up the right incentives for us. We survive because we run it like a business."

Just as incubators come in different forms, their size also varies. The largest, measured by land area, is Science Park in New Haven, Connecticut, with 10 buildings on 80 acres. The Charleston Business and Technology Center in South Carolina has the greatest number of tenants—147 in one building. The University City Science Center in Philadelphia consists of 1,100,000 square feet sprawled over 10 square blocks and divided among approximately 100 tenants. Their proudest boast: graduating over 500 businesses. In addition, California is home to the largest incubator in the Western U.S.—the San Pedro Venture Center.

Model Incubator

Unlike the traditional incubator in the East, where older buildings were used for facilities, San Pedro boasts of "modern, clean, new surroundings and a 1,000-line Centrex communication system from Pacific Bell," states Manager Frans Verschoor. "We've also just opened a 5,000- square-foot pre-school daycare center, built according to state requirements at a cost of $100,000, that can accommodate 45 children. Operated by the local YWCA, which is paying $1 annually for rent, its central location means parents will never be further than 800 feet, or one minute, from their children," Verschoor comments.

"The pre-school center, the first we know of nationwide in an incubator setting, was constructed in recognition that the requirements of time have changed the traditional roles of women, who are now equally part of the workforce. The growth of single-parent families is also a factor. Having on-site daycare facilities helps the parent, the employer, and the child."

The San Pedro Venture Center, which opened in September 1988, will ultimately house 125 tenants in 11 buildings situated on 10 acres. It currently provides office suites (492 to 785 square feet) or combination office/warehouse spaces (584 to 1,400 square feet), each of which functions as a totally independent unit. Each unit has air conditioning/heating, lights, blinds, restroom, and transformer (to provide a range of power from normal household to industrial strength). All a tenant needs to bring is a desk and chair to set up operations. Each unit is individually alarmed, and connected to a central system complete with camera surveillance.

Not only space, but leases are flexible, unlike typical five-year contracts, it would require a minimum of only six months. While there is no long-term obligation, most tenants signed up for three years.

A host of "pay as you use them" services is available for tenants, including a fax machine, photocopying, and secretarial services, a conference room (with another under construction that will accommodate up to 400 people for seminars and social gatherings), mailroom, and staffed reception area. These services are provided at cost; the developers receive their income solely from rent.

Verschoor has also negotiated with service firms in the Los Angeles area (including accounting, tax, marketing, legal, advertising, and business planning) which have agreed to give sizeable discounts to San Pedro Venture Center tenants. "Not only does this give tenants access to first-rate counsel," Verschoor emphasizes, "but the arrangement makes sense for the consultants. A small company today could be a Fortune 500 in the future."

Additionally, the center can connect tenants with funding sources, both public and private, and has hooked up with NASA's computer database—the largest in the world—which, in Verschoor's words, "is ready to go when tenant needs for information so require."

While Verschoor uses the number of new tenants—now averaging one a week—as one indicator of success, he is most proud of the resultant job creation. "We're located within the San Pedro/Wilmington Enterprise Zone, where the goal is to establish 1,350 new and lasting jobs within the next five years. In its first five months of operation alone, the San Pedro Venture Center created 30 of those jobs."

Incubator Benefits

Business

It's clear that retail incubators can significantly cut down on a start-up's overhead. They allow entrepreneurs to focus on the development of their ventures, rather than on the more mundane aspects of running a business. As a former incubator tenant in Washington, D.C., comments: "Why should you deal with issues such as what phone system or Xerox to buy? It makes far more sense to rent space in an incubator and concentrate on the success of your business."

Community

In addition to surveying companies, incubation professionals, and community stakeholders, the research team conducted a macroeconomic study in four communities to analyze the expanded impacts of incubators, such as how many direct and community spin-off, or "indirect," jobs they add and what effect they have on the tax base.

The return on investment was clearly healthy. "Looking at the operating subsidies these incubators received and the jobs and local taxes they produced, we estimate the return on public investment at $4.96 for every $1 of public operating subsidies," says Larry Molnar. This calculation did not include state or federal taxes, he notes. "The numbers make it clear that business incubators add considerable resources to—not take resources from—their communities," Molnar adds.

The research team confirmed another important fact about incubators: They are not all alike. Although some impacts were similar regardless of incubator type, other impacts related directly to an incubator's mission and goals.

"For instance, firms in all types of business incubators had similar average increases in their annual gross revenues. But firms from technology incubators created more jobs than other types of incubators," says team member Lou Tornatzky, director of the Southern Technology Council, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina. Incubators that are focused on low-income people and minorities were rated high by their community stakeholders in assisting minorities and women business owners and enhancing the business climate. The study divided incubators into three main categories according to the main types of firms served—mixed use, technology, and empowerment/neighborhood revitalization. There are many other subtypes, though, including manufacturing, arts, software, kitchen, and multimedia incubators.

Phases of Project

For planning purposes it will be beneficial to divide the project into phases and establish the timelines for each distinct phase. The usual divisions are: Feasibility (average time is three months); Development (average nine months); Renovation (average time ranges from three months to one year); and the Early Stage Operations during which the project will experience operational losses (average time is 18 months.) The delineation of each phase's time period is particularly important for those phases that occur after you "sign on the line" as owners or lessees of a facility, thus incurring fixed operational costs.

The availability of funds may necessitate that the renovation work on the facility be divided into phases. Certain sections of the facility may have to remain undeveloped until operating revenues generate enough to support increased mortgage, another tenant is located, or there is an allocation of operating budget revenues for renovation of the next phase.

We will identify portions of the facility we will probably lease first. Create a leasing schedule and, if possible, we will attempt to lease in concentrated areas of the building. Certain portions of the facility may be leased to tenants before renovations while other portions could be used during renovations.

When we formulate the project's classifications and timeline, we will remember that each situation is unique. Though this section sites the most commonly used divisions in the planning process many projects "go their own way" and may require classifications which are exceptions to these rules.

There are four phases in the incubator development process: preliminary planning, initiation and start-up, fine-tuning operations, and growing client firms. The following is a snapshot of the first phase.

- Preliminary Planning —Identify potential stakeholders. These will be the movers and shakers in our community: the successful entrepreneurs, politicians, administrators and community activists who are tied to economic development. After identifying stakeholders, we will get a good handle on their goals and objectives.

- Conduct a Needs Assessment —Identify local entrepreneurial base and gaps in the existing business and financial services for entrepreneurs in the community and barriers to accessing these services. This information would come directly from the entrepreneurs. This assessment will also let us know if the community's entrepreneurs and stakeholders mesh. This could be accomplished by facilitating a strategic planning session to allow the stakeholders and project developers to step back and take a look at the implications of their goals and objectives. Also a focus group would be developed of both experienced and start-up entrepreneurs in the sessions.

- Choosing the Right Real Estate —The following items will be taken into account when choosing a building: zoning, building codes, location factors, traffic, hazards, leasable space, security, insurance, access to facilities, material flow, staging areas, floor loads, ventilation, heating and cooling, electrical service, and plumbing.

- Evaluate Organizational Issues, Financing Options —Identify the relationship between the owner, the developer, and management. At this point, the decisions on legal structure of the incubator ownership and evaluation of potential sources of financing for development and operations.

- Determine Support Services and Operating Pro Forma —Determine the composition, organization, pricing and legal structure of shared services, management assistance, consulting, and business financing programs. To determine these factors we would do an operating scheme for the incubator—based on acquisition or site costs, construction costs, market analysis, rental rates, and lease-up schedule.

- Select a Management Team and Finalize Business Plan —Select a management team that is committed to the community, have sympathy for the need of start-up businesses, flexible, creative, steady under stress, high level of interpersonal skills, and they can mentor, administrate, handle public relations, facilitate and can be a friend. Included in our business plan will be preliminary drawings and a client outreach recruitment plan, fine-tuned construction costs, market and economic information, monthly cash-flow projections for the next five years, description of management team, description of legal and organization structure. We will then nail down our financing—get lenders, grantors, and equity partners to come up with money to start the project.

Service Programs

Our service program will precede the operation of the business incubator. A good business assistance service program will serve as one of our most effective tenant and client recruitment tools. Recruiting will begin well in advance of the availability of space for lease. It would be quite acceptable to begin our service delivery up to a year in advance of available space for lease or facility occupancy.

Our service program will be more concerned with the content and quality of each service provided rather than the number of services provided.

The typical management assistance service programs include office practice services, general management assistance services, and technical services. The following list is a sample of one menu of services provided by a business incubator located in Pennsylvania that has been in operation for more than three years.

Level One—Office Practice Services:

- Clerical services

- Switchboard services

- Voice mailbox/electronic mailbox

- Telephone equipment

- Least cost routing for telephone calls

- FAX service

- Postal service

- Overnight courier service

- Notary services

- Photocopier

- VCR/TV equipment station

- Audiovisual equipment rental

- Conference room

- Canteen and coffee service

- Sports ticket purchasing

- Auto service discounts

- Audiotape/videotape/journal clip services

- Annual exhibit event

- Group purchasing/warehouse membership

- Furniture rental

- Laser printing and clip art graphics

- Printing services

- Exhibit area

- Desktop Publishing Services

- Workshops/Seminars

Level Two—Management Services:

- Capital formation

- Customized job training

- Entrepreneurial classes/training

- Technical and commercial communications

- Technical writing—second draft

- Bookkeeping/accounting

- Facts about starting and operating a business in Michigan

- Legal referral

- One hour legal briefings

- New Venture Developments

- Business Plan preparation

- Employment services

- Maintenance of facilities/equipment

- Micro-loans

- Shipping and receiving services

- Marketing service sampler

-

Marketing

–Direct mail campaign

–Worksheet series

–Federal/state procurement

–Offense/defense tactics

–Panel presentation

–Export assistance

–Market research

–Printed circuit design

A portion of these services will be offered at first for little or no fee in order to introduce and stimulate initial usage per client. This would be equivalent to a special introductory offer.

It is possible that our management assistance program would charge a fee unless our program's third party funding support restricts or prohibits charging a fee.

We will be proactive in order to generate and maintain a sufficient client base for the service program. One strategy to build our client base volume necessary to continue development of the service program is to accept nontenant client companies.

Program Management

Responding to an informal e-mail survey and phone interviews by the NBIA, business incubator managers said that their programs' successful entrepreneurial firms had the following characteristics:

- An effective management team that works cooperatively and consists of members selected to provide a range of knowledge and skills

- Sound financing, the earlier the better. Funding is directly related to a firm's success, and in some cases it can be the deciding factor between a business venture's success or failure

- Principals that are able to focus on a lead product or service, and avoid over-investing in development and diversification

- Principals that make business decisions based on a clear understanding of the market and the competition, rather than their own enchantment with their product or service

- Principals that keep on top of best business practices by surrounding themselves with knowledgeable people, by remaining open to their advice and ideas, and by being willing and ready to make changes based on new information

- A well-researched business plan in place that provides clear direction and focus

- Principals that are good money managers and remain in control of the venture's books

- Entrepreneurs who are passionate about their ventures and communicate that excitement to potential funders, customers, and mentors.

Entrepreneurial failures often lacked some or all of these elements, according to survey respondents.

The incubator manager should be able to explain why business planning is important, both during start-up efforts and afterwards. Some firms may never prepare a business plan, because they aren't eligible for venture capital, for instance, but they are the same companies that tend to make "seat-of-the pants decisions," and to lack a clear vision of their future.

Principles of the Incubator

As listed in the NBIA Regional Training Institute curriculum, these 10 principles state that incubators should:

- Concentrate on the development or collection of support services that nurture start-up or emerging businesses. Providing below-market rental rates should not be the primary focus of the incubator.

- Value growth and development of individual companies beyond their ability to pay rent.

- Be judged on their ability to create new businesses or help nurture emerging companies, not on the number of jobs directly created. Successful, growing businesses will create employment opportunities.

-

Be structured so that the property element takes a secondary position

relative to programs since serving businesses is the core of quality

incubation programs. However, the facility can offer the following

tangible and intangible benefits:

a. a positive cash flow resulting from successful incubator facilities management

b. a centralized place for entrepreneurs to meet

c. a focus for small business support programs in the community

d. opportunities for valuable interchanges among entrepreneurial firms - Be viewed as one possible component of an integrated, overall, regional economic development plan and be designed to reflect the strengths and weaknesses of the region.

- Be structured so that program outcomes match both the short-and long-term benefits required by sponsors.

- Work from a clear mission statement with quantifiable goals and objectives tied to an evaluation process which rewards quality performance.

- Be run by highly skilled, street-smart managers who are willing to wear a large number of hats, e.g., those of: general business counselor, triage nurse, facilities manager, psychologist, investment banker, etc.

- Recognize the inevitable tension faced by the manager, who functions as both advocate for the companies and landlord of a facility.

- Set up and run operational policies and systems in a business like fashion.

Staffing

Many incubation programs are hard to staff. A number of "pressures" on the incubator program drive up expenses and drive down revenue. Many business incubation programs respond to these income pressures by restructuring their staff in one of the following ways:

- Balancing the duties and responsibilities of the incubator manager between facility management and the delivery of management assistance services to the tenant companies. If the duties and responsibilities do not emphasize the management assistance side of the equation, most managers will spend the majority of their time on the property and will neglect client services.

- Carefully considering the need to have a full-time staff member attend to the central switchboard and clerical/word processing services for the tenant companies. This is a key position. The switchboard is the lifeline of communication between the incubator and its marketplace. The impression of the incubator's quality is most influenced by the style and content of the switchboard services. The skill to operate a switchboard is rare. Many secretaries have clerical skills and consider the switchboard a "prison sentence." Someone who enjoys the interaction of a switchboard and has word processing skills as well is invaluable.

- A full-time switchboard/word processing staff person with a part-time manager is more effective than a full-time manager and a part-time switchboard/word processing staff person. If we can afford to have both positions full-time, that is great. However, many incubation projects are forced to operate with part-time staff support and you cannot have a part-time switchboard service: business communication requirements are not part-time. Management assistance, however, can be scheduled into a part-time manager's work week.

-

Utilizing community organizations' school-to-work and on-the-job

training participants, is another way of addressing staffing needs. This

concept accomplishes two objectives:

a. It helps community organizations to place their program completers

b. It maintains an ongoing pool of incubator staff candidates.

Targeting a Facility

The following steps will be used to reach an acquisition lease price for using a facility as a business incubator.

- We will examine floor plans and use our best judgment to sketch partitions on the floor plans to accommodate tenant spaces of 140, 400, 1,100, 3,000, and 6,000 square feet. For each large space we will have two spaces of the next smaller size.

- Measure the linear feet of each designated area.

- Measure the net rentable square feet of the partitions.

- Grade and label our leasable spaces A, B, C, or D based on the quality of the space and its location.

- Seek input from three or four commercial realtors regarding market lease rates for similar property and set our market value at the average.

- Calculate the potential revenue at full occupancy by listing A space at full market value, B space at 90 percent of market, C space at 80 percent of market, and D space at 70 percent of market. The total is our potential full occupancy revenue.

- Starting with this potential full occupancy figure, we will subtract 8 percent for vacancy and 6 percent as bad debt expense.

- Next we will subtract at least $.90 but no more than $1.40 per square foot for contributions toward our service program and staff.

- We then will subtract fixed costs for taxes, insurance, etc.

- By calculating $.90 per square foot for maintenance, cleaning, and repairs, we will subtract it from our balance. The rate can be adjusted up or down depending upon the condition of the facility.

- This final figure is the amount we may spend on a lease or mortgage at "full occupancy," regardless of when this is achieved.

-

We will follow a conservative schedule of what we anticipate will be

leased to tenants such as:

a. 10 percent pre-leased

b. 40 percent lease-up achieved by end of year one

c. 50 percent lease-up achieved by end of year two

d. 80 percent lease-up achieved by end of year three - These steps can determine what we will have available for lease or mortgage payments through the first three years.

We will then ask ourselves the following questions: Is there is enough money to support our monthly payment with the anticipated subsidy for the first there years? Is there enough money to support an unsubsidized program at "full occupancy"?

If the answer is yes, we will hire an engineer to corroborate our partitioning plan and construct a rough estimate of our renovation costs. If not, we will go back to the property owner to renegotiate and acquisition cost or lease rate.

Based on both the engineer's assessment of renovation and the evaluation of our leasing plan, we can weigh the advantages and disadvantages of constructing a new facility versus proceeding with acquisition and renovation.

Industry "Rules of Thumb"

- We should be able to demonstrate that the facility will break even at 67 percent occupancy or less.

- We will need at least 30,000 square fee gross space to have any hope of breaking even.

- The candidate facilities that look the best financially would be our targeted facilities. We will need to focus on what the facility will generate in income as an incubator than on the actual market value of the property. The purchase price will be dictated by our calculations.

- Having collected the operating data and renovation estimates, we would then be ready to negotiate a tough acquisition price and terms payment.

Strategic Planning Issues

As development plans are prepared, there are a number of strategic issues that need to be addressed. The issues listed below represent very important, basic questions that will be answered as we move forward with the program.

- Who will fund the phases of this program?

- Will this program be place on a plan to self-sustain?

- How large should the facility be?

- How should we structure management assistance services within the program?

- What comes first?

Most business incubators struggle to attain break-even operating status. Those that generate an operating surplus usually achieve returns on investment that would not excite an investor. Many business incubation programs fall victim to sustaining a difficult facility and having client bases that do not generate user fees sufficient to meet management and office practice costs.

Hopefully, our program will generate regular operating profits or our program's budget and cash flow will never become a concern. The income potential of a building can increase its market value and, hopefully, each audit will show an increase in the physical assets of the corporation so our facility's assessed value will increase our net worth annually.

Most business incubators that achieve self-sustaining operations have more than 30,000 square feet of net rentable space and can generate revenues more than $1.50 per square foot above facility fixed costs. However, with very few exceptions, business incubators cannot support adequate returns on investments to more than one stakeholder organization.

Funding Sources

Retail incubators have received loan and grant funding from literally hundreds of public and private funding sources. The following are a few planning issues to be considered relating to funding:

- A. Establishing a nonprofit public or private corporation that will offer access to the widest range of funding sources.

- B. If we plan on accessing federal funds from an organization such as EDA we will plan on allowing nine months to one year for a decision.

- C. After our investment in facility renovation/acquisition, we will plan on raising funds to cover an average of 18 months of operational losses.

- D. Federal and state public funds to support business incubators are growing in number and dollar volume allocated.

- E. Most business incubators have not received grant funding support beyond three years.

- F. We will research the dozens of ways to structure the acquisition or lease of the facility that involve creative financing techniques with the seller that will produce far greater cost savings benefits than do most third party grants and loans.

- G. Unfortunately, there are more funding sources available for facility acquisition and renovation than for service delivery and early stage operational losses.

- H. It is difficult to repay money borrowed for delivery of services and the early stage operational losses of our facility unless we have a substantial return on our leasing plan once we achieve a high occupancy rate. We may be able to support these early stage operational losses via debt financing if the money we borrow is a program-related investment from a foundation. The program-related investment usually provides us with a long-term, unsecured, zero-interest loan.

- I. It is now easier to raise grant funds for new construction than it has been in the past.

-

J. We have to beware of agreements accompanying the acceptance of a

grant such as:

Agreement to have tenant companies sign lease agreements with strict employment clauses.

Agreeing to create dramatic job growth in early years.

Agreeing to maintain the incubator program for 15 years or longer. - K. Beware of being pressured into undercapitalizing our project.

- L. Within our proposal narrative we will discuss the entrepreneurs and prospects we have met, surveyed, and served rather than to speak philosophically about our marketing approach for locating tenant prospects.

- M. If training must be offered as a condition to our funding, we will make sure that training includes nontenant business training as well as tenant company training.

- N. Establish a for-profit organization and utilize venture capitalists.

Marketing Strategy

Underlying the retail incubator marketing plan is an exploration of the question: Are there prospective customers for a business incubation program in this community? The following questions are suggested to serve as a catalyst to stimulate some creative ways of identifying collection points where our prospective clients may congregate.

- Are there any clusters of businesses that appear to be significant or emerging in markets that appear to have a positive near-term future?

- If so, what do these cluster companies purchase in some volume that could be supplied locally?

- Do the owners of these cluster companies ever meet together?

- What topics would attract these prospective entrepreneurs to attend a meeting at which the incubation program plan could be introduced and discussed?

In addition to answering these four questions, we would identify a minimum of five or more key contact points in the community whom new entrepreneurs can call or visit to receive information and resources to start their company. These contacts would be educated on the objectives of the incubation program. These contacts would also refer to the incubator those entrepreneurs who show the best promise of business survival and who express an interest in facilities which offer an accompanying access to services.

Identifying these key contact points and answers to the preceding questions will help us to locate potential clients. It will also be important for us to be able to assess the demand for a business incubation program. In addition to conducting a traditional survey and collecting demographic statistics, an alternative approach of assessing client demand will be to offer a demonstration of some components of our management assistance services program. We can then gauge an indication of demand by recording the number and type of participants who access our services.

These services can be demonstrated by a variety of ways: one-day workshops, a series of workshops, one-on-one counseling assistance, etc. These ongoing workshops provided by the incubator will be designed to help the program assess the level of entrepreneurial activity in the area as well as to market the incubator itself.

Once we have gathered this information allowing us to identify sources of potential clients as well as assess market demand for management assistance services, we will be ready to consider other important questions as we prepare our marketing plan.

- How can we position ourselves, our staff, and board to initiate marketing and sales activities rather than just to react to opportunities for promoting our program?

- Do we plan to escrow/allocate funds for marketing and sales activities?

- Do we us the word "incubator" as the primary descriptor to prospective tenants?

- Do we split our potential customers into vertical segments to help target special features of our program to customers?

- Do we have plans to develop a "constancy of purpose" among our staff and stakeholders regarding the continuing development and effective implementation of our marketing plan.

- Do we have plans to establish a "track system" to guide our staff and board through the correct process of presenting the facilities and services of our program to prospective tenants?

- Do we have a clear statement of how we are distinguished from your competitors?

- Are we planning to become an active member in our state and national incubation associations?

- Will our marketing materials focus primarily on what just happened vs. what is planned to happen?

- Will our incubation program staff and service providers have regular planning sessions to focus on new services for our existing clients and to plan activities that demonstrate our services to prospective clients?

- Will we actively use our clients' successes to market to target groups?

Creative Funding Strategies

Because financial resources are limited, one solution we will use is to be creative in negotiating acquisition, renovation, lease agreements, and leasehold improvements. We will use the following suggestions to get our creative thought processes flowing.

- A. Remember to ignore the asking prices on the property/facility. Do our calculations as detailed and make an offer to purchase or lease based on the income value of the property—not the market value.

- B. Request that seller carry a portion of the lease/mortgage, receiving monthly payments based on a graduated scale as defined by a prorated three-year lease plan. This will allow us to pay more only after we have rented a larger percentage of our space.

- C. Consider capital equipment needs and seek contributions for the phone system, office equipment, furniture, etc., from companies that manufacture and/or sell these products.

- D. Ask area banks to pool funds via a CRA plan for leasehold improvements. Then base our leasehold improvements on tenant loans a few percentage points higher than CRA terms, amortizing the payments to the length of the leases. This will enable us to have the tenants pay for more of the capital improvements as well as encourage longer lease agreements.

- E. Permit the anchor tenant to sublease to others as long as the tenant agrees to commit to a larger square foot area than they currently need, but eventually plan to utilize. Give them a lower rate on the extended space allowing them to gain a margin of income on that space.

- F. Include the rental space, leased furniture, and a package of office practice services in one flat rate monthly charge. When using this method, we will calculate the square foot rate of this office at double our normal lease cost. The services fee should be calculated at an hourly rate based on defined usage—assume the maximum number of hours whether or not they use their full allotment. The sum of all three factors equals the monthly charge.

- G. Determine whether the seller has the opportunity to obtain a tax deduction for the amount of the difference between the market appraisal and the sales price. Such a tax deduction would create an incentive for the seller to discount the sale price by the net effect of the tax deduction.

- H. Attempt to restrict grant funds to a specific portion of the facility in order to increase project flexibility and leverage other sources of debt equity.

- I. Identify our net rentable lease units as A, B, C, or D grade space. Attempt to package A space with some B, C, and/or D space per tenant. This will prevent the possibility that we will rent the A space first and experience the increased difficulty of lease the B, C, and D space. Price the lease rates accordingly.

Community Reinvestment Act (CRA)

The CRA, revised in 1989, offers the incubation industry two opportunities: to obtain bank participation in an incubator development project, and to obtain money for revolving loan funds or other lending programs in order to extend credit to incubator tenants and the small- and minority-business community.

Banks can fulfill some of their CRA compliance factors related to their effectiveness in communicating with—and working with—community groups by participating in the development of a business incubator. There are a number of services the incubators can provide to banks with good data about what's happening economically in their neighborhoods and alert banks to the latest neighborhood business trends. Additionally, they can provide banks with a wide range of services including helping to review loan packages and other technical assistance.

Incubation Part of Policy Statement

After a broad-based community task force assesses the credit needs of the community—which is always the first step—it is commonly found that almost every market reports the same needs: financing for small businesses for working capital and for fixed assets. This would be included in the needs statement, the policy statement asks the banks to come with a plan to address these needs. And that's where an incubator can fit in.

The CRA implementation plan can specifically include funding for an incubator project or loans for incubator clients and small businesses.

Raising Awareness

Federal Reserve states that "Support of small business incubator programs affords institutions an opportunity to provide other services which can stimulate small-business development. These activities, in our view, would be included as part of an institution's record of performance under CRA."

Washington added that this communiqué, received in November 1988, placed incubator projects under the category of "other activities" in which financial institutions may engage in order to receive CRA credits. According to Washington, banks can help incubators address two pressing needs: funding for incubator project and loans for start-up businesses.

According to Washington, an incubator looking to secure these kinds of CRA-related funds from banks must first participate in the formation of a community group such as a city-county reinvestment task force. This task force represents all segments of the community, which is responsible for coordinating and assisting with the assessment of needs and eventually developing a plan.

Funding for projects is not a given. An incubator has to be a viable project and be on the alert for opportunities to promote its work.

Banks must be shown that incubators can offer them a good deal that will help them meet the regulators' CRA expectations.

One group meets with a consortium of seven banks. The group meets with top officers once a month to help them meet CRA requirements. This group has adequate information about their real estate transactions, where they might be lagging behind and what they may do to better market their services in terms of meeting CRA requirements.

Blending bank funds with government and foundation sources creates a solid building block and helps the incubator to be viewed as less risky. The incubator can also engineer some other CRA-related deals: seed capital and subordinate loan pools to help meet the needs of minorities and underserved people in the community.

Another way a bank can help is to provide scholarships for low-income entrepreneurs and owners of small businesses or start-ups to take classes.

The retail incubator can also assist with providing a one-on-one service covering the "pre-application" loan process for a possible citywide seed-capital revolving loan fund; this service can be funded by the Small Business Development Center (SBDC).

Utilizing the CRA is an excellent way for our incubator to leverage financial support, both for ourselves and, perhaps more importantly, our tenants.

Empowerment Zone Initiatives

In December of 1994, Detroit, Atlanta, Baltimore, Chicago, New York, and a partnership of Philadelphia and Camden were awarded empowerment zones.

Detroit's winning proposal was the result of many people representing the community and the gamut of public and private organizations throughout Detroit and the metropolitan area. The vision expressed, the projects proposed, and the commitment guaranteed, truly set Detroit's proposal apart from any of the other submissions.

According to a the Jackson Journal article dated September 27, 2000, and entitled "Gore envisions cash aid for Jackson," it is possible that Jackson, Michigan, may have another opportunity to apply for an empowerment zone designation. A state-of-the-art business incubator could play a role in the strategic plan to outline programs and strategies aimed at reducing the effects of poverty in the inner city. It could also assist in bringing together unlikely groups of community residents, city and state officials, and representatives of local business and financial institutions to work side by side to determine the best ways to address poverty issues in their communities.

The business incubator will also assist with the framework of the EZ/EC programs' four key principles:

- Economic Opportunity, including job creation within the community and throughout the region, entrepreneurial initiatives, small business expansion, and training for jobs that offer upward mobility

- Sustainable Community Development, to advance the creation of livable and vibrant communities through comprehensive approaches that coordinate economic, physical, environmental, community, and human development

- Community-Based Partnerships, involving participation of all segments of the community, including the political and governmental leadership, community groups, health and social service groups, environmental groups, religious organizations, the private and nonprofit sectors, centers of learning, other community institutions, and individual citizens

- Strategic Vision for Change, which identifies what the community will become and a strategic map for revitalization

Since the aim of the EZ/EC Initiative is to serve as a catalyst for locally generated strategies, its accountability can be assured through the development of benchmarks such as a business incubator. The initiative's design reflects the benefit of prior experience and knowledge of successful economic development efforts by combining targeted tax incentives with such things as direct financial assistance, job readiness training and placement services, improvements to physical infrastructure and public safety, and the development of strong community partnerships shown to be essential for long-term success.

Like Detroit, Jackson can also empower itself through the strength of a city committed to a new economic future. Our future can also be built upon:

- New economic foundations blending business into the neighborhood, linking training and jobs to Zone residents, offering real access to new financial resources

- The proposed Zone's new vitality can succeed by citywide and regional cooperation. We can build and maintain a positive flow of employment, capital and innovation. Each section of our Plan can also demonstrate a commitment to build new bridges across all economic and social sectors, while removing barriers between citizens, government, foundations, institutions, and our regional neighbors.

By sponsoring small business incubators in their state, state governments can encourage local economic growth through job creation and job retention, the revitalization of underutilized property and the establishment of public-private partnerships.

Partnering for Economic Development

As a focal point of entrepreneurial activity, our business incubator may provide key leadership to the new business formation component of our community's economic development plan.

The most important planks in our economic development plan are retention and expansion of new businesses. The other area of economic development has to do with all of those areas that affect business development. It includes education, taxation, infrastructure, and availability of financing—whether you are expanding or relocating or creating a new business.

After looking at who's doing what in our community and how we are accomplishing our overall economic development, the city, county, and private sector are becoming more educated to the significance of new business formation and to the role it could play in Jackson's economic development.

By bringing together the Jackson Chamber of Commerce, Small Business Development Center, Community Capital Development Corporation, Jackson Area Investment Fund, colleges and universities, Small Business Administration, Business Information Center, Women's Business Center, City of Jackson, Michigan Minority Business Development Center, Enterprise Community, Career Alliance, Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce, Jackson County Planning Commission, HUD, and our local banks into a partnership, we could create a Council of Small Business Enterprises (COSBE). The retail incubator will be the nucleus of these community partnerships and for a new business council component in our economic development plan. This concept can continue to grow by forming linkages with other organizations interested in economic growth.

National Business Incubator Association (NBIA)

Membership in NBIA

A key alliance and support system for the proposed Jackson business incubator will be our membership with the National Business Incubation Association (NBIA). It is the world's leading organization advancing business incubation and entrepreneurship. It provides thousands of professionals with the information, education, advocacy, and networking resources to bring excellence to the process of assisting early-stage companies. It is also the world's largest membership organization for those involved with business incubation programs, and it is committed to advancing the business incubation industry by providing research, technical assistance, and educational opportunities for business incubation professionals, business service providers, investors, and others involved in helping start-up businesses grow and thrive.

NBIA Activities

NBIA offers professional development activities and specialized training to help business assistance professionals create and administer effective incubation programs. The Association's public awareness activities educate entrepreneurs, public sector leaders, corporations, and investors on the benefits of business incubation. NBIA also conducts research, compiles statistics, produces publications that provide hands-on approaches to developing and managing effective programs, tracks relevant legislative initiatives, and maintains a speakers' bureau and referral service. It creates partnerships with leading private-sector and public-sector entities to further the interests of the industry and its members.

Who belongs to NBIA?

- Incubator executive directors, managers, and staff

- Incubator developers and researchers

- Business assistance professionals

- Economic development professionals

- University-related research park managers

- Corporate joint venture partners

- Industry consultants

- Venture capital investors

- Educational institutions

- People exploring feasibility of business incubation for their communities

- Anyone interested in business incubation

NBIA Objectives

- Provide information, research, and networking resources to help members develop and manage successful incubation programs

- Monitor and disseminate knowledge of industry developments, trends, and best practices

- Inform and educate leaders, potential supporters, and stakeholders of the significant benefits of incubation

- Build public awareness of business incubation as a valuable business development tool

- Expand capacity to create valuable resources for members through partnerships

- Engage and represent all segments of the industry

- Create value for members

Member Benefits

- Subscription to NBIA Review and NBIA Updates

- NBIA Member Directory

- Access to members-only section of NBIA website

- Eligibility to join NBIA's member-only listserve

- Information research, referral, documentation, and dissemination service

- Legislative and government program updates

- Special money-saving programs for goods and services with leading providers

- Targeted member mailings including industry press releases and media tool kit

- Eligibility to vote in NBIA elections and run for the NBIA board

Members-only Discounts on:

- NBIA bookstore purchases, including important publications for incubator managers, developers, and clients

Incubator Risks and Failures

Incubator developers are always interested in what makes an incubator work. But we found it can be more useful at what makes an incubator fail. We found there to be five main stumbling blocks to success.

- Expecting too much too quickly. The dynamics behind incubators can be very complicated, which means everything does not come together as quickly as a real estate operation might. But people don't understand that. Some developers believe they can acquire a building and put out a sign shortly thereafter. They fully believe that once the incubator opens, the jobs and companies will flow in. This type of expectation leads to frustration and dissatisfaction at best and failure at worst. Developers also must manage expectations of the public. This is always tough. When city councils and economic development administrators get involved in a job creation goal, they want the community to see immediate results. But they must be made to understand that it takes two to five years for most companies to become viable in the marketplace.

- Selecting the wrong manager. Because the incubator manager is the key person running the incubator—and sometimes the only person—he or she must be well-rounded, well-organized, have good business sense, and be a skilled networker. The latter is especially important. The ability to gain resources and cooperation from important institutions, individuals, and organizations often spells the difference between success and failure.

- Overestimating the incubator's role. Economic development planners can make the error of viewing an incubator as a cure-all for economic growth. It can make a significant contribution, but it cannot cure all the economic ills of a region. The existence of an incubator most likely won't influence a large industry to relocate, for instance. Incubators can make a contribution to expansion and retention of industries already in a region by training, expanding and providing additional resources to companies there. The most important purpose of an incubator is to work with entrepreneurs to accelerate the development of emerging companies. That must be the key focus of management. Thinking that incubators are there to create jobs is a mistake; jobs follow the companies, not vice versa.

- Overspending. Some incubators don't understand the dynamics of their own business—and an incubator is a business after all. The ability to manage cash flow and stay within the boundaries of the operating budget are as critical to incubators as they are for any business.

- Failure to leverage resources. It takes an incubator a few years to get running and become financially stable. Developers must set a realistic timeframe, then leverage resources. As an example, the Austin Technology Incubator in Texas looked for funding for three years out. Its city council committed to $50,000 a year for each three years. The Chamber of Commerce put in $25,000 a year for each of the three years. The incubator raised $50,000 a year from private sources. In addition to that, private companies—such as accounting, law, and marketing firms—made three-year commitments of in-kind support amount to about $100,000 a year. Resources are thus leveraged and, as a bonus, a lot of people gain a stake in the incubator's success. Although Austin did not start out doing so, more incubators are taking equity in client companies as another important leveraging tool.

Funding Needs

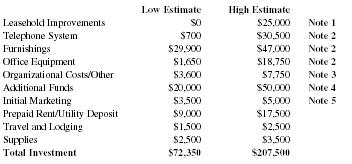

Until a building has been located and our calculations completed it is difficult to pinpoint exact funding needs. According to NBIA, the average start-up of a business incubator is between $72,320 to 207,500. The breakdown is as follows:

| Low Estimate | High Estimate | |||

| Note 1. Real Estate costs include the cost of modifying a leasehold to meet criteria for business incubator standards. The cost of such leasehold improvements may be paid by the landlord as a part of the lease negotiation, or may be paid by the Proprietor. These costs have been estimated to be from $0 to $25,000. | Note 2. Total purchase price for this item is represented by the high estimate figure. The equipment may be purchased through a vendor. The initial investment under an equipment lease is represented by the low estimate figure which includes a deposit and six month's payments. Furnishings include desks, chairs, and file cabinets for clients. | Note 3. Organizational Costs include the cost of attorney fees, financial advisors, and other costs associated with the new company. | Note 4. This figure includes cash reserves for the initial start-up period, including salary for Proprietor or General Manager. This is an estimate, and there is no assurance that additional capital will not be necessary during the start-up period. | Note 5. This figure represents costs of an initial marketing and public relations campaign. |

| Leasehold Improvements | $0 | $25,000 | Note 1 | |

| Telephone System | $700 | $30,500 | Note 2 | |

| Furnishings | $29,900 | $47,000 | Note 2 | |

| Office Equipment | $1,650 | $18,750 | Note 2 | |

| Organizational Costs/Other | $3,600 | $7,750 | Note 3 | |

| Additional Funds | $20,000 | $50,000 | Note 4 | |

| Initial Marketing | $3,500 | $5,000 | Note 5 | |

| Prepaid Rent/Utility Deposit | $9,000 | $17,500 | ||

| Travel and Lodging | $1,500 | $2,500 | ||

| Supplies | $2,500 | $3,500 | ||

| Total Investment | $72,350 | $207,500 |

Summary

Retail incubators are proven tools for creating jobs, encouraging technology transfer, and starting new businesses. Set up to assist in the growth and development of new enterprises, incubators are themselves a growth industry. In 13 years, their number has increased thirty-fold, to more than 500 in 1993. A new incubator becomes operational each week, on average. More than 9,000 small firms currently reside in incubators; thousands more are program "graduates," having moved on to occupy commercial space within their communities.

Retail incubators accelerate the development of successful entrepreneurial companies by providing hands-on assistance and a variety of business and technical support services during the vulnerable early years. Typically, incubators provide space for a number of businesses under one roof with such amenities as flexible space and leases; office services and equipment on a pay-as-you-go basis; an on-site incubator manager as a resource for business advice; orchestrated exposure to a network of outside business and technical consultants, often providing accounting, marketing, engineering and design advice; assistance with financing; and opportunities to network and transact business with other firms in the same facility. Incubators reduce the risks involved in business start-ups, and their young tenant companies gain access to facilities and equipment and equipment that might otherwise be unavailable or unaffordable.

Our incubation program's main goal is to produce successful graduate-businesses that are financially viable when they "graduate" from the incubator, usually within two or three years of entering the program. Research shows that more than 80 percent of firms that have ever been incubated are still in operation. And research on graduates by Coopers & Lybrand has found that these graduates are increasing revenues and creating jobs.

Formalization of the industry was accelerated from 1984 through 1987 by the active involvement of the U.S. Small Business Administration's Office of Private Sector Initiatives. Under the direction of John Cox, now SBA's Director of Finance and Investment, the agency held a series of regional conferences and published a newsletter and several incubator handbooks.

The National Business Incubation Association was formed by industry leaders in 1985, and by 1987 was recognized as the main source of information on incubators. NBIA's membership today numbers over 700 and is primarily composed of incubator developers and managers. Its mission is to provide training and a clearinghouse for information on incubator management and development issues and on tools for assisting start-up and fledgling firms. This organization will provide the technical support and research needed, plus ongoing support in the developmental and completion stages of our incubator.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: