FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM

The Federal Reserve System is the central bank of the United States. The Fed is exclusively a banker's bank and does not conduct commercial banking activities. Its goal is to attain stable economic growth in the nation, and through its actions, influence the flow of money and credit in the economy. Specifically, the Fed is responsible for:

- formulating monetary policy;

- acting as lender of last resort for the nation's banks and depository institutions;

- facilitating the collection and clearance of checks;

- regulating and supervising banks and other financial institutions;

- acting as fiscal agent for the United States Treasury;

- distributing coin and currency to the public through depository institutions; and

- implementing certain regulations of consumer credit legislation.

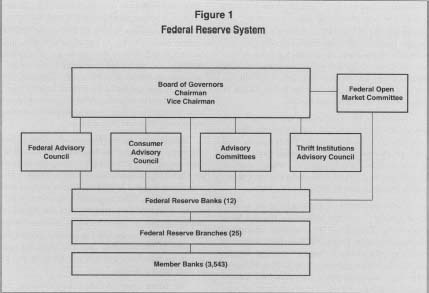

The system consists of the Board of Governors, the Federal Open Market Committee, 12 Federal Reserve Banks, 25 branches, member financial institutions, and advisory committees.

THE FORMATION OF THE FEDERAL

RESERVE

The historical roots of the Federal Reserve System extend back to 1791. Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury under George Washington, advocated the establishment of the First Bank of the United States. Hamilton believed the nation needed a central bank for several reasons. First, a central bank would facilitate the creation of banking establishments throughout the United States and generate a greater supply of bank credit to aid economic growth. Second, the monetary and fiscal responsibilities of

Congress as enumerated in the Constitution were so great that a central bank was needed to carry out those activities. Finally, a central bank could serve the Treasury in its revenue collection and distribution functions. Although Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson opposed Hamilton's plan, the 20-year charter for the First Bank of the United States passed in 1791.

The First National Bank of the United States proved to be a successful and profitable institution, but a bill to recharter the bank was defeated in Congress. Opponents, primarily the state-chartered banks, argued the bank had monopoly power and was under the influence of foreign owners. The bank ceased operations in 1811, and America's banking system was thrown into a tailspin. The number of state-chartered private banks increased dramatically, creating a hodgepodge of bank notes and disrupting the system of interregional payments. With the outbreak of the War of 1812, the federal government's finances fell into disarray. At this time, many Americans thought the monetary activities of the nation's banks required federal regulation. As a result of these conditions, a bill to charter the Second National Bank of the United States was introduced and passed by Congress in 1816, the final year of James Madison's presidency.

The Second National Bank developed a powerful and effective system of monetary regulation under the leadership of Nicholas Biddle (1786-1844), its president from 1823 to 1839. Biddle hoped to expand the bank's role in America's economy, but as the bank became more powerful, many citizens feared it was a threat and menace to democracy. President Andrew Jackson distrusted the central bank's authority, believing it was an instrument of the rich and powerful. The 1832 bill to recharter the bank passed both houses of Congress, but Jackson vetoed the bill. Nicholas Biddle resigned as president in 1839 and the bank finally ceased operations in 1841.

In the absence of a central bank authority, the state-chartered banks once again filled the gap with a patchwork system subject to violent fluctuations in the monetary system. The United States Treasury assumed some central banking responsibilities such as open market securities purchases. Clearinghouse associations also performed some responsibilities normally under the jurisdiction of a central authority. The associations issued clearinghouse loan certificates, which became a important type of "emergency currency" for banks during financial panics. Regulatory activities, such as controlling member banks' interest rates on deposits and conducting member bank examinations, were also carried out by the associations.

The National Banking Act (formerly the National Currency Act) of 1863 instituted a system of nationally chartered banks subject to strict capital requirements. Three types of national banks were recognized: country banks, reserve city banks, and central reserve city banks. The country banks were required to keep a portion of their reserves in vault cash and the remainder with a national bank in a reserve or central reserve city in the form of vault cash. Reserve city banks had to keep a portion of their reserves as vault cash and the remaining portion as a deposit in a national bank at a central reserve city. The central reserve city banks in New York, Chicago, and St. Louis were required to keep all their reserves as vault cash.

Under this system circulating bank notes had to be backed by the holdings of United States government securities. State bank notes eventually ceased circulating, but state banks continued to thrive. Checking accounts rather than bank notes provided the revenue these banks required to operate.

The primary weaknesses of the national banking system were an inelastic supply of currency and the immobile reserves. The currency supply did not expand and contract as appropriate with the cycle of business, and the pyramid structure of country, reserve city, and central reserve city banks meant reserves were not readily available when needed. As a result the economy suffered wild cycles of boom and bust.

Congress passed the Aldrich-Vreeland Act of 1908 after the financial panic of 1907. One of the most important provisions of the act was the creation of the National Monetary Commission. Under the direction of its chairman, Senator Nelson W. Aldrich of Rhode Island, the commission studied the nation's financial system over three years. The final report, known as the Aldrich Plan, recommended the creation of a central banking system.

Acting on the findings of the Aldrich plan, Representative Carter Glass (1858-1946) of Virginia and H. Parker Willis (1874-1937), an expert adviser to the House Committee on Banking and Finance, drafted the Glass-Willis proposal and presented it to President Woodrow Wilson. Initial opposition to the bill was voiced by Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan. Bryan argued the proposal allowed bankers too much influence over the system and failed to weaken the Wall Street "money trust," a small group of finance leaders with vast control over the nation's money and credit. He also believed the government and not the reserve banks, as the Glass Willis proposal specified, should be empowered to issue currency. Other opponents included city bankers and agrarian leaders. After many changes and compromises, the revised bill was introduced by Glass and Senator Robert Owen of Oklahoma in the House and Senate.

Eventually the Owen-Glass bill passed both houses of Congress, and the Federal Reserve Act became law on 23 December 1913. The law enumerated three primary purposes of the Federal Reserve System: to provide an elastic supply of currency, a means to discount commercial credits, and a system of supervision and regulation over the nation's banks.

The responsibility of implementing the system, as designated by the law, fell to the Reserve Bank Organization Committee. The committee consisted of the Secretary of the Treasury William G. McAdoo, the Secretary of Agriculture David F. Houston, and the Comptroller of the Currency John Skelton Williams. After many meetings across the nation with various leaders of banking, finance, and government, the committee completed its task and the Federal Reserve Banks opened for business 16 November 1914.

The structure of the Federal Reserve System is based on five components: the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Open Market Committee, the Federal Reserve Banks, member banks, and advisory committees. Figure I illustrates the organizational relationship of these components.

THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS

The Board of Governors, frequently called the Federal Reserve Board, represents the ultimate authority of the Federal Reserve System. Located in Washington, D.C., the board consists of seven members, mostly professional economists, appointed by the President of the United States and confirmed by the Senate. The full term of a member's appointment is 14 years, and it is not possible to be reappointed. The terms are staggered to provide a system of checks and balances so one member's term expires every even-numbered year. Members usually retire before completing the term. The board's chairman and vice chairman, appointed by the president with the advice and consent of the Senate, serve four-year terms and their positions may be renewed provided they have not exceeded their terms as board members. The chairman is the most well-known and visible representative of the Federal Reserve System.

The primary responsibility of the board is to determine and implement monetary policy. However, the board devotes the most time to regulatory and supervisory activities. The board exercises ultimate supervisory and regulatory authority over the Federal Reserve Banks, bank holding companies, and Federal Reserve System banks. As part of these responsibilities the Board decides the percentage of deposits member banks must hold as reserves. It also reviews and approves the rate of interest, or the discount rate, charged to member banks for Federal Reserve loans. The Board works with other federal agencies to determine the maximum interest rates offered by member banks on savings and time deposits.

Additionally, the board supervises a wide variety activities in areas such as bank mergers, consolidations, acquisitions, international banking operations in the United States, operations of member banks in foreign countries, and interest regulation on time and savings deposits. Other responsibilities include supervision of the nation's payment system and regulatory implementation of consumer credit and community affairs laws such as the Truth in Lending Act and the Community Reinvestment Act. The board also approves all presidents and vice presidents of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks.

The board reports to Congress periodically, and its chairman acts as one of the principal economic advisers to the president and Congress. Detailed statistics and other information about the system and the board's activities are available through publications such as the Federal Reserve Bulletin and the board's annual report.

THE FEDERAL OPEN MARKET

COMMITTEE

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) consists of seven members from the Board of Governors and five presidents from the 12 Federal Reserve Banks. The Chairman of the Board of Governors also serves as the committee chairman. Four of the five slots occupied by bank presidents rotate on a yearly basis, and the fifth slot is permanently held by the New York district bank president. Those presidents not currently serving on the committee usually attend and participate in meetings but do not vote. Traditionally, the president of the New York bank is elected vice chairman of the committee. Meetings are usually held eight times a year, but the committee may consult as needed between these dates.

The most important function of the Federal Open Market Committee is to determine and direct the open market operations for the Federal Reserve. Open market operations are purchases or sales of securities in the nation's money and bond markets that affect the level of reserves financial institutions hold. The FOMC's operations also extend to the international exchange market where foreign currencies are traded. Each Federal Reserve Bank may not execute open

Federal Reserver System

The Federal Reserve Bank presidents play an important role on the FOMC. Although every president does not vote at every meeting, the presidents provide a sense of balance in the direction of open market operations. As representatives of their individual districts, their presence ensures the Fed will remain a decentralized entity as the original architects intended.

THE FEDERAL RESERVE BANKS

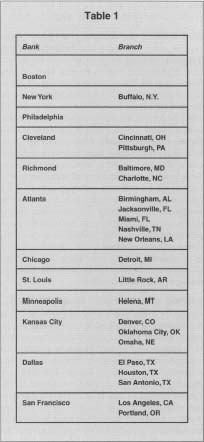

The 12 Federal Reserve Bank districts are headquartered in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Richmond, Atlanta, Chicago, St. Louis, Minneapolis, Kansas City, Dallas, and San Francisco. The 25 branch banks in each district are shown in Table 1 (the Boston bank has no branches). The stock of each Federal Reserve Bank is owned by the respective district member banks as required by the membership guidelines. However, stock ownership does not confer the privileges of financial or controlling interest as does common stock ownership.

Each Reserve Bank has its own board of nine, part-time outside directors that supervises the general operations of each bank and elects each bank's officers. The directors are classified as either Class A, B, or C directors. Three Class A directors, representing commercial banks from their districts, are elected to the position by the district member institutions. Three Class B directors are also elected by district member banks, but Class B directors may not be employees, officers, or directors of any bank. Class B directors must be active representatives of commerce, agriculture, labor, or other industrial sectors within the district. The remaining three directors for each bank, the Class C directors, are appointed by the Board of Governors. The Class C directors also may not be employees, officers, directors, or stockholders of any bank. One of the Class C directors is designated the chairman of the bank's board and one is designated deputy chairman. Small, medium, and large member banks each vote for one Class A and Class B director to maintain a system of checks and balances and prevent the interests of large institutions from dominating the board. All directors are elected for three-year terms on a staggered basis.

A president, first vice president, and other officers for each bank are appointed by the board at each Federal Reserve Bank with the approval of the Board of Governors of the Federal System. The president receives a five-year term. Many activities fall within the authority of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks. Among the most important are:

| Bank | Branch |

| Boston | |

| New York | Buffalo, N.Y. |

| Philadelphia | |

| Cleveland |

Cincinnati, OH

Pittsburgh, PA |

| Richmond |

Baltimore, MD

Charlotte, NC |

| Atlanta |

Birmingham, AL

Jacksonville, FL Miami, FL Nashville, TN New Orleans, LA |

| Chicago | Detroit, Ml |

| St. Louis | Little Rock, AR |

| Minneapolis | Helena, MT |

| Kansas City |

Denver, CO

Oklahoma City, OK Omaha, NE |

| Dallas |

El Paso, TX

Houston, TX San Antonio, TX |

| San Francisco |

Los Angeles, CA

Portland, OR |

- Each bank's board establishes the discount rate subject to the approval of the Board of Governors.

- The banks act as depository and fiscal agents for the United States Treasury and other government agencies.

- The banks act as regional clearinghouses and collection agents for depository institutions collecting checks and other instruments.

- Reserve or clearing balances for depository institutions are held at the Reserve Banks in accordance with the Monetary Control Act of 1980.

- The Federal Reserve Banks act as representatives of their districts to the Federal Reserve System by providing information concerning local business and financial conditions. This information is critical to the decision-making process of monetary policy. The Banks also act as representatives of the Fed in their respective business communities.

The Reserve Banks also operate the two national electronic funds transfer (EFT) systems, Fedwire and Automated Clearinghouse (ACH). These systems facilitate interbank and intergovernmental transfer of funds via electronic record-keeping rather than physical currency or checks. Fedwire is used primarily for large transactions by the government, depository institutions, and large businesses. As of 1997 Fedwire supported over 90 million transactions a year. The average Fedwire transaction at that time was worth several million dollars. ACH is the more commonly used system for ordinary wire transfers and electronic payments among businesses and individuals. As such, it carries a very large volume of transactions—2.6 billion in 1997—but the net value of those transactions is much lower, averaging just several thousand dollars each.

MEMBER BANKS

As of year end 1997, 3,543 banks were members of the Federal Reserve System, representing more than 45,000 individual bank branches. Member banks include many of the United States' largest and best-known commercial banks, including national and state-chartered banks. National banks, chartered by the Comptroller of the Currency, are required to be members of the Federal Reserve System. State-chartered banks may become members if certain requirements, established by the Board of Governors, are met and the board gives final approval. As a member of the Federal Reserve System, each institution is required to hold stock in its respective Federal Reserve Bank and is subject to the supervision of the Reserve Banks. Member institutions elect six of the nine members to each Federal Reserve Bank's board and receive an annual dividend on the Reserve Bank stock.

Prior to 1980 many state-chartered banks opted not to become members of the Federal Reserve System because of the relatively high reserve requirements imposed by membership in the system. Nonmember banks only had to meet the lower reserve requirements imposed by their state authorities. The Monetary Control Act of 1980 established that all depository institutions, regardless of their status as members or non-members, are subject to the reserve requirements of the Federal Reserve System. The act also expanded access to the Federal Reserve services, which were previously restricted to member institutions, with explicit fees for various services.

ADVISORY COMMITTEES

Several advisory committees and councils facilitate the flow of operations and communication within the Federal Reserve System. The Federal Reserve Act created the Federal Advisory Council consisting of one member from each Federal Reserve District. Members are selected by the board of directors at each Reserve Bank on an annual basis and are usually prominent bankers in the district. The council meets at least four times a year in Washington, D.C., to discuss general business issues and monetary policy matters with the Board of Governors.

The Consumer Advisory Council also meets with the Board of Governors at least four times each year. Composed of 30 members, the group represents the interests of consumers and creditors. Its function is to advise the Board of Governors on such matters related to the Fed's authority in the areas of consumer and creditor laws.

The Thrift Institutions Advisory Council, established in 1980 with the Monetary Control Act, provides information related to issues and concerns of thrift institutions. The council is composed of representatives from savings banks, savings and loan associations, and credit unions. It meets at least four times every year.

A Small Business and Agricultural Advisory Committee exists at each Federal Reserve Bank. The committee advises each bank on business conditions within its respective area. Some members of these committees meet with the Board of Governors each year.

MONETARY POLICY

Considered the most important responsibility of the Federal Reserve, monetary policy refers to the actions undertaken to influence the availability, cost, and release of reserves at depository institutions, which in turn loosens or tightens the money supply. The money supply, in turn, influences employment, investment, and ultimately, inflation.

The primary tools of monetary policy are the discount rate, open market operations, and reserve requirements.

DISCOUNT RATE.

The discount rate is the interest rate charged by each of the Federal Reserve Banks on loans made to financial institutions. Each bank's rate is reviewed and approved by the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. An institution with reservable deposits may borrow from the "discount window" for short-term purposes on a limited basis, and the rates are usually similar across districts. High rates tend to result in decreased borrowing for reserves, and low rates tend to result in increased borrowing depending on the level of reserves institutions hold.

OPEN MARKET OPERATIONS.

Open market operations are purchases or sales of securities (usually U.S. Treasury bills and notes) in the open money and bond markets. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York acts as the Fed's agent by executing the operations as directed by the Federal Open Market Committee on a continuous basis. These operations directly affect the level of reserves held by depository institutions at Federal Reserve Banks and, as a result, affect the nation's money supply. When the Fed buys securities on the open market, bank reserves increase, and conversely, when it sells, bank reserves decrease. Since banks must maintain a certain minimum level of reserves, the result of open market transactions is that banks will either have excess reserves that can be repurposed for something else—loosening money supply—or have a reserve deficit that requires them to pull money in from other activities to cover the reserves—tightening money supply. The money supply is an important factor in determining the availability of credit, interest rates, prices, and other important measures of financial condition.

RESERVE REQUIREMENTS.

All depository institutions in the United States, regardless of whether they are members of the Federal Reserve System, are required to hold reserves against certain accounts at their institutions. The reserves may be held as either vault cash or deposits at a Federal Reserve Bank as a determined percentage of deposit liabilities. The Banking Act of 1933 extended the authority of the Federal Reserve to vary these reserve requirements, and under the Monetary Control Act of 1980 the Board of Governors may impose these requirements on transaction deposits and on nonpersonal time deposits for the sole purpose of executing monetary policy. Changes in the reserve requirement affect the supply of money in the economy. Raising the reserve requirement decreases any excess reserves an institution may hold by transforming the reserve's status from excess to required. Thus, raising the requirement limits a bank's ability to expand deposits.

INTERNATIONAL OPERATIONS

The Fed is also regularly engaged in a variety of international operations. Some of these are purely regulatory or logistical, such as overseeing cross-border banking and coordinating with central banks of other leading countries. One of the most important international policy functions of the Federal Reserve is, along with the U.S. Treasury, to maintain stability in the foreign exchange currency markets. In particular, the Fed attempts to support the U.S. dollar at exchange rates that are consistent with broader U.S. economic health and stability. Currency fluctuations can either help or hinder U.S. exports, for example, and can severely affect certain economic sectors. Therefore, the Fed guards against the dollar growing too strong or too weak against principal world currencies such as the German mark and the Japanese yen. It does so through transactions on the currency exchange markets, e.g., buying or selling marks. Such transactions may be done in cooperation with the respective foreign governments.

LENDER OF LAST RESORT

In its role as lender of last resort, the Federal Reserve makes loans to financial institutions in times of crisis when funds are not available through any other means. It is an important tool to help avoid monetary panics and ensure the nation's financial stability.

CHECK CLEARING

Each Federal Reserve Bank acts as a regional clearinghouse to exchange or" clear" checks deposited at one institution but written on another institution. The Fed also "settles" checks by moving the funds as required from payee to payer institution. Other Fed payment services include wire transfers and automated clearinghouse services using magnetic tapes.

REGULATION AND SUPERVISION

The Federal Reserve System has both regulatory (rule making) and supervisory (monitoring and en forcing) responsibilities. A few of these duties include:

- supervision of all bank holding companies, including their mergers and acquisitions;

- oversight of some 900 state-chartered banks that are members of the Federal Reserve System;

- supervision and regulation of foreign banking operations in the United States; and

- regulation of U.S. commercial banking activities in foreign countries.

The Fed's supervisory functions also involve directly monitoring and inspecting member institutions to ensure they are observing legal and sound practices.

Other federal banking regulatory agencies include the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS), the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), and the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, which consists of ranking members from several of the federal agencies. State-chartered banks are also regulated by state agencies.

UNITED STATES TREASURY FISCAL

AGENT

The Federal Reserve is independent of the U.S. Treasury, but the Federal Reserve works with the Treasury in formulating economic policy and carrying out the day-to-day fiscal tasks as Treasury's "bank." The Treasury has an account with the Federal Reserve to transfer funds and to handle the payment and clearance of Treasury obligations.

DISTRIBUTION OF CURRENCY AND COIN

The Federal Reserve Banks utilize the depository institutions within their respective districts to enter or remove coin and currency from circulation. Each institution's account at the bank is credited if excess cash is returned or charged if additional cash is requested. The banks also remove worn and damaged currency from circulation through this mechanism.

CONSUMER CREDIT LEGISLATION

The Consumer Credit Protection Act assigned certain responsibilities to the Federal Reserve System. The most important pieces of legislation included in the act were the Truth in Lending Act, the Fair Credit Billing Act, the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, and the Electronic Funds Transfer Act (EFTA). The Fed is responsible for writing regulations and implementing the laws to ensure the provisions of the acts are followed and enforced. The Fed is also involved in implementing and supervising community related acts such as the Community Reinvestment Act and the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act.

FEDERAL RESERVE AUTONOMY

The architects of the Federal Reserve Act sought to create a central banking authority free from the political and industrial pressures which may try to influence the course of its operations. Therefore, the Federal Reserve is not under the jurisdiction of any department and is an independent agency within the federal government. Although the member institutions own stock in the Federal Reserve Banks, members do not control or own the Fed. The president and Congress do possess some influence over the Fed, and many sections of the system maintain close relationships with other federal departments on a formal and informal basis; however, the leadership of the Federal Reserve is generally free to develop and execute monetary policy as it sees fit.

SEE ALSO : Interest Rates ; Macroeconomics

[ Paula M. Ard ]

FURTHER READING:

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 84th Annual Report, 1997. Washington, 1998. Available from www.federalreserve.gov .

——. The Federal Reserve System: Purposes & Functions. 8th ed. Washington, 1994. Available from www.federalreserve.gov .

Broz, J. Lawrence. The International Origins of the Federal Reserve System. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997.

Corder, J. Kevin. Central Bank Autonomy: The Federal Reserve System in American Politics. New York: Garland, 1998.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: