INCOME STATEMENT

An income statement presents a company's revenues and expenses for

a given

accounting

period, e.g., a month, quarter, or year. Also called a statement of

earnings or a statement of operations, the income statement compares a

company's revenues with its expenses during a specific period. The

difference between the two is a company's net

income

(or net loss). A company's net

income

for an accounting period is measured as follows:

The income statement provides information concerning return on investment, risk, financial flexibility, and operating capabilities. Return on investment is a measure of a firm's overall performance. Risk is the uncertainty associated with the future of the enterprise. Financial flexibility is the firm's ability to adapt to problems and opportunities. Operating capability relates to the firm's ability to maintain a given level of operations.

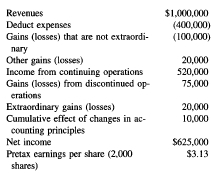

The current view of the income statement is that income should reflect all items of profit and loss recognized during the accounting period, except for a few items that would be entered directly under retained earnings on the balance sheet, notably prior period adjustments (i.e., correction of errors). The following summary income statement illustrates the generally accepted accounting principles used when preparing these financial statements:

| Revenues | $1,000,000 |

| Deduct expenses | (400,000) |

| Gains (losses) that are not extraordinary | (100,000) |

| Other gains (losses) | 20,000 |

| Income from continuing operations | 520,000 |

| Gains (losses) from discontinued operations | 75,000 |

| Extraordinary gains (losses) | 20,000 |

| Cumulative effect of changes in accounting principles | 10,000 |

| Net income | $625,000 |

| Pretax earnings per share (2,000 shares) | $3.13 |

Although income statements measure revenues, expenses, etc. in terms of dollars, these figures do not necessarily correspond to specific amounts of cash a company has. For example, a company most likely does not have the amount of cash corresponding to its net income on an income statement. Instead, this figure represents both the actual cash the company has received as well as promises from customers and clients to pay the company for products and services purchased on credit. Nevertheless, companies record revenues when they earn them and expenses when they incur them, not when they actually receive cash. This practice is referred to as the accrual basis of accounting.

ELEMENTS OF INCOME STATEMENTS

The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) establishes the definitions of key elements of the income statement, such as revenues, expenses, gains, and losses. Revenues (sales) refer to the total amount of money a business earns by selling its products or by providing its services during a specific period. Revenues also include money earned from dividends, interest, and royalties. Expenses refer to the total costs a company incurs for doing business in a specific period, such as the cost of materials, supplies, labor, leases, and utilities. In addition, expenses must directly relate to generating revenues for a company. Materials and utilities are obvious expenses, because a company needs both materials and utilities to manufacture and sell products.

Gains are increases in the excess of what a company owns over what it owes (owners' equity) from peripheral or incidental transactions of a business entity and from all other transactions and events affecting the company during the accounting period, except those that result from revenues or investments by owners. Examples are a gain on the sale of a building and a gain on the early retirement of long-term debt. Losses are decreases in owners' equity from peripheral or incidental transactions of a business entity and from all other transactions and events affecting the entity during the accounting period, except those that result from expenses or distributions to owners. Examples are losses on the sale of investments and losses from litigation.

Discontinued operations are those operations of an enterprise that have been sold, abandoned, or otherwise disposed. The results of continuing operations must be reported separately in the income statement from discontinued operations. In addition, any gain or loss from the disposal of a segment must be reported along with the operating results of the discontinued separate major line of business or class of customer.

Extraordinary gains or losses are significant events and transactions that are both unusual in nature and infrequent in occurrence. Both of the following criteria must be met for an item to be classified as an extraordinary gain or loss:

- Unusual in Nature: The underlying event or transaction should possess a high degree of abnormality and be clearly unrelated to, or only incidentally related to, the ordinary and typical activities of the business, taking into account the environment in which the business operates.

- Infrequency of Occurrence: The underlying event or transaction should be of a type that would not reasonably be expected to recur in the foreseeable future, taking into account the environment in which the business operates.

Extraordinary items could result if gains or losses were the direct result of any of the following events or circumstances: a major casualty, such as an earthquake; an expropriation of property by a foreign government; and a prohibition under a new act or regulation.

Gains and losses that are not extraordinary refer to significant financial transactions that are unusual or infrequent, but not both. Such items must be disclosed separately above "income (loss) before extraordinary items."

An accounting change refers to a change in accounting principle, accounting estimate, or reporting entity. Changes in accounting principles result when an accounting principle is adopted that is different from the one previously used. Changes in estimate involve revisions of estimates, such as the useful lives or residual value of depreciable assets, the loss for bad debts, and warranty costs. A change in reporting entity occurs when a company changes its composition from the prior period, as occurs when a new subsidiary is acquired.

Net income, or the "bottom line," is the excess of all revenues and gains for a designated period over all expenses and losses of that period. Conversely, net loss is the excess of expenses and losses over revenues and gains for a designated period.

Generally accepted accounting principles—the principles and conventions that govern accounting—require the disclosure of earnings per share amounts on the income statement of all publicly held companies. Earnings per share data provides a measure of the enterprise's management and past performance and enables users of income statements to evaluate future prospects of the enterprise and assess dividend distributions to shareholders. Disclosure of earnings per share for effects of discontinued operations and extraordinary items is optional, but it is required for income from continuing operations, income before extraordinary items, cumulative effects of a change in accounting principles, and net income.

THE RECOGNITION PRINCIPLE

The revenue recognition principle provides guidelines for reporting revenue in the income statement. The principle generally requires that revenue be recognized in the financial statements when: (1) realized or realizable and (2) earned. Revenues are realized when products or services are exchanged or performed for cash or claims to cash. Revenues also are realizable when a company's things of monetary value (assets), such as products and debts owed to the company, are readily convertible into cash. Revenues are considered earned when a business has substantially accomplished what it must do to be entitled to the benefits represented by the revenues. Recognition through sales or the providing (performance) of services provides a uniform and reasonable test of realization. Limited exceptions to the basic revenue principle include recognizing revenue during production (on long-term construction contracts), at the completion of production (for many commodities), and subsequent to the sale at the time of cash collection (on installment sales).

In recognizing expenses, accountants rely on the matching principle because it requires that efforts (expenses) be matched with accomplishments (revenues) whenever it is reasonable and practical to do so. For example, matching (associating) the cost of goods sold with revenues from the interrelated sales that resulted directly and jointly from the same transaction as the expense is reasonable and practical. To recognize costs for which it is difficult to adopt some association with revenues, accountants use a rational and systematic allocation policy that assigns expenses to the periods during which the related assets are expected to provide benefits, such as depreciation, amortization, and insurance. Some costs are charged to the current period as expenses (or losses) merely because no future benefit is anticipated, no connection with revenue is apparent, or no allocation is rational and systematic under the circumstances, i.e., under an immediate recognition principle.

The current operating concept of income includes only those value changes and events that are controllable by management and that are incurred in the current period from ordinary, normal, and recurring operations. Any unusual and nonrecurring items of income or loss would be recognized directly in the statement of retained earnings. Under this concept of income, investors are primarily interested in continuing income from operations.

In the late 1990s, however, the FASB moved closer to adopting all-inclusive or comprehensive income reporting. The all-inclusive concept of income includes the total changes in equity recognized during a specific period, except for dividend distributions and capital transactions. Unlike the previous concept of income, this concept requires companies to include unusual and nonrecurring income or loss items in their income statements for the appropriate accounting period.

CONSOLIDATED INCOME STATEMENTS

Accountants prepare consolidated income statements by combining the revenues, gains, expenses, and losses of a parent company's accounts the accounts of its subsidiary operations. A subsidiary is a company with more than 50 percent of its voting stock owned by a parent company. Revenues and expenses that result from transactions between parent and subsidiary companies—intercompany transactions—are not included or are eliminated because they do not affect the assets of the overall company, when viewed as a consolidted operation. Intercompany transactions include sales between parent and subsidiary companies and rent received from or paid by affiliated companies to each other.

FORMATS OF THE INCOME STATEMENT

The income statement can be prepared using either the single-step or the multiple-step format. The single-step format lists and totals all revenue and gain items at the beginning of the statement. All expense and loss items follow the revenue and expense items. Finally, the total expenses and losses are deducted from the total revenues and gains, yielding the net income.

The multiple-step income statement, on the other hand, presents operating revenue at the beginning of the statement and nonoperating gains, expenses, and losses near the end of the statement. Various items of expenses, however, are deducted throughout the statement at intermediate levels, providing useful subtotals along the way. The statement is arranged to show explicitly several important amounts, such as gross margin on sales, operating income, income before taxes, and net income. At the first step, the cost of products sold is deducted from the net revenues. At the second step, operating expenses are deducted. At the final step, nonoperating revenues are added and nonoperating expenses are subtracted resulting in the net income. Extraordinary items, gains and losses, accounting changes, and discontinued operations are always shown separately at the bottom of the income statement ahead of net income, regardless of which format is used.

Each format of the income statement has its advantages. The advantage of the multiple-step income statement is that it explicitly displays important financial and managerial information that the user would have to calculate from a single-step income statement. The single-step format has the advantage of being relatively simple to prepare and to understand.

SEE ALSO : Financial Statements

[ Charles Woelfel ,

updated by Karl Heil ]

FURTHER READING:

Eisen, Peter J. Accounting. 3rd ed. Hauppauge, NY: Barron's Educational Series, 1994.

Financial Accounting Standards Board. Statements of Financial Accounting Concepts. Homewood, IL: Irwin, 1986.

Hendriksen, Eldon. S., and M. F. Van Bred. Accounting Theory. Homewood, IL: Irwin, 1992.

Label, Wayne A. 10-Minute Guide to Accounting for Nonaccountants. New York: Alpha Books, 1998.

Lueke, Randall W., and David T. Meeting. "How Companies Report Income." Journal of Accountancy, May 1998, 45.

Meigs, Robert F., and Walter B. Meigs. Accounting: The Basis for Business Decisions. I th ed. Homewood, IL: Irwin, 1998.

Weiss, Donald. How to Read Financial Statements. New York: AMACOM, 1986.