SIC 2282

YARN TEXTURIZING, THROWING, TWISTING, AND WINDING MILLS

Establishments included in this classification are those that are primarily engaged in texturizing (or texturing), throwing (another name for texturizing), twisting, winding, or spooling purchased yarns or manmade fiber filaments wholly or chiefly by weight of cotton, manmade fibers, silk, or wool, mohair, or similar animal fibers, or in performing such activities on a commission basis. Establishments primarily engaged in dyeing or finishing purchased yarns or finishing yarns on a commission basis are classified in SIC 2231: Broadwoven Fabric Mills, Wool (Including Dyeing and Finishing) if the yarns are of wool, and in SIC 2269: Finishers of Textiles, Not Elsewhere Classified if they are of other fibers. Establishments primarily engaged in producing and texturizing manmade fiber filaments and yarns in the same plant are classified in SIC 2823: Cellulosic Manmade Fibers.

NAICS Code(s)

313112 (Yarn Texturing, Throwing and Twisting Mills)

313312 (Textile and Fabric Finishing (except Broad-woven Fabric) Mills)

Industry Snapshot

According to the U.S. Bureau of the Census, roughly 130 establishments operated in this classification in the early 2000s. These businesses shipped $3.7 billion worth of products in 2001. Material costs totaled $3.4 billion, and capital expenditures were $240 million. North Carolina had by far the largest concentration of establishments in this industry, followed by Pennsylvania, Alabama, California, and New Jersey. Unifi Inc. of Greensboro, North Carolina, was the world's largest texturizing company with $849 million in 2003 sales and 4,500 employees.

Texturizing is a process whereby partially oriented filament yarn (POY) is stabilized through heating and drawing. This produces a crimped continuous filament yarn. Generally speaking, two types of manmade POY are texturized: nylon and polyester. Texturized nylon is used primarily in the manufacturing of ladies' hosiery. Texturized polyester is used in various apparel and home furnishings products and, to a lesser extent, in industrial fabric. There are two types of texturizing machines; most POY products are texturized on false-twist texturizing machines, but some are made with air-jet texturizing machines.

Organization and Structure

POY comes to the texturizing plant wound on tubes, which serve as the supply packages for the texturizing machines. These are purchased from manmade fiber producers such as DuPont, Eastman Chemical Co., Hoechst Celanese, Tollaram Fibers, American Micrell, and Well-man. These packages contain anywhere from 10 to 100 pounds of POY. To receive the more economical, larger packages, a texturizing plant must be equipped with automated package-handling equipment, which has been available since 1990. Some older plants, especially those involved in small niche markets, opted not to purchase the automated equipment and must order the smaller package size.

Most texturized yarn is produced by companies such as Unifi for sale to weaving and knitting establishments. Some weaving plants, such as Burlington Industries and Milliken & Co., produce yarn for their own consumption. Texturizing machines are not manufactured in the United States; instead, false-twist and air-jet texturizing machines are made by companies in Europe and Japan.

Background and Development

Texturizing is relatively new compared to other segments of the textile industry, most of which have been around for centuries. The beginnings of texturizing go

back to the invention of nylon more than 50 years ago when texturizing was used to process nylon yarn for hosiery. The new industry blossomed in the 1970s as the system to produce polyester filament yarns for use during the double-knit polyester craze. As rapidly as double-knit polyester leisure suits grew in popularity, texturizing grew as a necessary process. Unfortunately for the more than one hundred polyester texturizing plants that sprang up overnight, polyester texturizing died with double-knit polyester leisure suits.

Despite its relatively young age, texturizing enjoyed more technological advances throughout the last two decades than any other textile process. The Textured Yarn Association of America (TYAA) formed in 1972 to establish quality standards for the fledgling industry. TYAA members learned at the association's twentieth anniversary meeting in July 1992 that since 1972, texturizing speeds had more than quadrupled and package sizes had tripled. Electronics now controlled operations, temperatures, speeds, and twists and monitored quality, temperature, and efficiency. Nearly every machine maker offered at least one model with automated features such as doffing, package handling, and creeling.

At the first organizational meeting, TYAA hosted more than 100 texturizing companies. Most of these were supplying yarn for the double-knit polyester trade. At TYAA's 1993 annual meeting, 10 texturizing companies were represented. By the mid-1990s, membership in TYAA included suppliers to the industry, users of texturized yarn, and companies who performed the texturizing process. Annual poundage for texturizing at TYAA's beginning was in the neighborhood of 1.6 billion. During the mid-1990s, the figure was something less than one billion, but the dollar value had increased substantially. Those companies who divorced themselves from the double-knit disaster were making products that required high-tech specifications and much higher quality.

Current Conditions

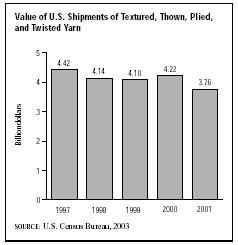

The U.S. Census Bureau reported that in 2000 this industry employed 20,801 people, including 18,679 production workers who earned an average hourly wage of $8.59. The value of shipments throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s declined, falling from $4.42 billion in 1997 to $3.76 billion in 2001. This decline was due in large part to increased competition from imports, as well as to the recessionary economic conditions in the United States that developed in the early 2000s.

The primary product of more than 40 establishments was textured, crimped, or bulked filament yarns, including stretch yarn made from purchased filament yarn. This segment shipped $2.5 billion worth of goods in 2001, compared to $3.09 billion in 1997. Material costs for this segment totaled more than two billion dollars.

The primary product of more than 30 establishments was thrown filament yarns, except textured yarns. This segment shipped $927.74 million worth of goods in 2001, compared to $1.02 billion in 1997. Materials costs for this segment totaled more than $700 million.

The primary product of roughly 10 establishments was novelty and plied yarns other than wool, not spun or thrown at the same establishment. Unlike other segments, sales for novelty and plied yarns increased in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The value of shipments increased from $156.84 million in 1997 to $208.31 million in 2001.

The primary product of less than 10 establishments was commission receipts for throwing or texturing of filament yarns. This segment also grew during the late 1990s and early 2000s. The value of shipments more than doubled between 1997 and 2001, growing from $43.21 million to $96.11 million.

Industry Leaders

Unifi Inc. (Greensboro, North Carolina) has long been the industry leader in texturizing in the United States. Unifi had 4,500 employees in 2003. Sales that year declined 7.2 percent to $848 million, and the firm posted a $27.2 million loss. Throughout the early 2000s, Unifi had struggled to deal with the impact of waning yarn sales, as well as falling prices. In an effort to increase its international presence, particularly in Asia, Unifi forged a partnership with Thailand-based Tuntex in the early 2000s.

Among other companies whose primary business was within this segment of the textile industry were Burke Mills Inc. (Valdese, North Carolina), which had 167 employees and 2002 sales of $30 million; Jefferson Mills Inc. (Pulaski, Virginia), which had 150 employees and sales of $26 million; and Modern Fibers Inc. (Fitzgerald, Georgia), which had 120 employees and estimated sales of $25 million.

America and the World

Yarn texturizing, along with the rest of the U.S. textile industry, increasingly competed in the global marketplace during the late 1990s and early 2000s. The world's growing population, developing world economies, the technical advantages of systems such as Quick Response and DAMA, and new trade agreements worked together to positively affect this segment of the industry. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which essentially removed all trade restrictions among Canadian, U.S., and Mexican businesses, helped the U.S. textile industry in some ways, but it also contributed to the closure of some U.S. textile mills and the reduction of operations at others.

Research and Technology

Research and technology have provided several new operating systems that have helped the U.S. textile industry remain competitive. One such system, Quick Response, creates partnerships up and down the soft goods pipeline—fiber producers, textile manufacturers, apparel manufacturers, and retail establishments—and uses electronic technology, especially bar coding and Electronic Data Interchange (EDI), to receive up-to-date information. When the process works as it should, the system overcomes some of the advantages held by establishments that export products from low-wage, developing countries into the United States.

In 1993 the American Textile Partnership (AMTEX) enacted a pact in which national laboratories, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), and the textile industry develop systems to make the industry more competitive. One AMTEX project, Demand Activated Manufacturing Architecture (DAMA), expands on the Quick Response system. Under the DAMA system, electronics inform pipeline partners of each garment sold by analyzing point-of-sale data generated when bar-coded hangtags are scanned. The DAMA pilot project, begun in 1996, has shown that an electronic marketplace will improve operations and reduce expenses by controlling warehouse costs and inventory size and reducing wastes. It will also improve customer responsiveness and product development. The impact of these systems on production and operations continued to be examined in the early 2000s.

Further Reading

U.S. Census Bureau. "Statistics for Industry Groups and Industries: 2000." February 2002. Available from http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/m00as-1.pdf .

——. "Value of Shipment for Product Classes: 2001 and Earlier Years." December 2002. Available from http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/m01as-2.pdf .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: