MANAGEMENT CONTROL

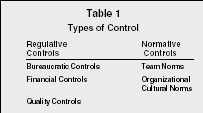

Management control describes the means by which the actions of individuals or groups within an organization are constrained to perform certain actions while avoiding other actions in an effort to achieve organizational goals. Management control falls into two broad categories—regulative and normative controls—but within these categories are several types.

Types of Control

| Regulative Controls | Normative Controls |

| Bureaucratic Controls | Team Norms |

| Financial Controls | Organizational Cultural Norms |

| Quality Controls |

The following section addresses regulative controls including bureaucratic controls, financial controls, and quality controls. The second section addresses normative controls including team norms and organization cultural norms.

REGULATIVE CONTROLS

Regulative controls stem from standing policies and standard operating procedures, leading some to criticize regulative controls as outdated and counter-productive. As organizations have become more flexible in recent years by flattening organizational hierarchies, expanding organizational boundaries to include suppliers in inventory management and customers in new product development, forging cooperative alliances with competitors, and developing virtual organizations in which employees are geographically dispersed and may meet only a few time each year, critics point out that regulative controls may prevent rather promote goal attainment.

There is some truth to this. Customer service representatives at Holiday Inn are limited in the extent to which they can correct mistakes involving guests. They can move guests to a different room if there is excessive noise in the room next to the guest's room. In some instances, guests may get a gift certificate for an additional night at another Holiday Inn if they have had a particularly bad experience. In contrast, customer service representatives at Tokyo's Marriott Inn have the latitude to take up to $500 off a customer's bill to solve complaints.

The actions of customer service representatives at both Holiday Inn and Marriott Inn must follow policies and procedures, yet those at Marriott are likely to feel less constrained and more empowered by Marriott's policies and procedures compared to Holiday Inn customer service representatives. The key in terms of management control is matching regulative controls such as policies and procedures with organizational goals such as customer satisfaction. Each of the three types of regulative controls discussed in the next few paragraphs has the potential to align or misalign organizational goals with regulative controls. The challenge for managers is striking the right balance between too much control and too little.

BUREAUCRATIC CONTROLS

Bureaucratic controls stem from lines of authority and this authority comes with one's position in the organizational hierarchy. The higher up the chain of command, the more an individual will have authority to dictate policies and procedures. Bureaucratic controls have gotten a bad name and often rightfully so. Organizations placing too much reliance on chain of command authority relationships inhibit flexibility to deal with unexpected events. However, there are ways managers can build flexibility into policies and procedures that make bureaucracies as flexible and able to quickly respond to customer problems as any other form of organizational control.

Consider how hospitals, for example, are structured along hierarchical lines of authority. The Board

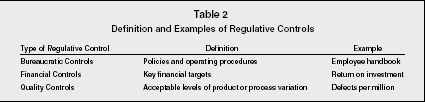

Definition and Examples of Regulative Controls

| Type of Regulative Control | Definition | Example |

| Bureaucratic Controls | Policies and operating procedures | Employee handbook |

| Financial Controls | Key financial targets | Return on investment |

| Quality Controls | Acceptable levels of product or process variation | Defects per million |

of Directors is at the top, followed by the CEO and then the Medical Director. Below these top executives are vice presidents with responsibility for overseeing various hospital functions such as human resources, medical records, surgery, and intensive care units. The chain of command in hospitals is clear; a nurse, for example, would not dare increase the dosage of a heart medication to a patient in an intensive care unit without a physician's order. Clearly, this has the potential to slow reaction times—physicians sometimes spread their time across hospital rounds for two or three hospitals and also their individual office practice. Yet, it is the nurses and other direct care providers who have the most contact with patients and are in the best position to rapidly respond to changes in a patient's condition.

The question bureaucratic controls must address is: How can the chain of command be preserved while also building flexibility and quick response times into the system? One way is through standard operating procedures that delegate responsibility downward. Some hospital respiratory therapy departments, for example, have developed standard operating procedures (in health care terms, therapist-driven protocols or TDPs) with input from physicians.

TDPs usually have branching logic structures requiring therapists to perform specific tests prior to certain patient interventions to build safety into the protocol. Once physicians approve a set of TDPs, therapists have the autonomy to make decisions concerning patient care without further physicians' orders as long as these decisions stay within the boundaries of the TDP. Patients need not wait for a physician to make the next set of rounds or patient visits, write a new set of orders, enter the orders on the hospitals intranet, and wait for the manager of respiratory therapy to schedule a therapist to perform the intervention. Instead, therapists can respond immediately because protocols are established that build in flexibility and fast response along with safety checks to limit mistakes.

Bureaucratic control is thus not synonymous with rigidity. Unfortunately, organizations have built rigidity into many bureaucratic systems, but this need not be the case. It is entirely possible for creative managers to develop flexible, quick-response bureaucracies.

FINANCIAL CONTROLS

Financial controls include key financial targets for which managers are held accountable. These types of controls are common among firms that are organized as multiple strategic business units (SBUs). SBUs are product, service, or geographic lines having managers who are responsible for the SBU's profits and losses. These managers are held responsible to upper management to achieve financial targets that contribute to the overall profitability of the corporation.

Managers who are not SBU executives often have financial responsibility as well. Individual department heads are typically responsible for keeping expenses within budgeted guidelines. These managers, however, tend to have less overall responsibility for financial profitability targets than SBU managers.

In either case, financial controls place constraints on spending. For SBU managers, increased spending must be justified by increased revenues. For departmental managers, staying within budget is typically one key measure of periodic performance reviews. The role of financial controls, then, is to increase overall profitability as well as to keep costs in line. To determine which costs are reasonable, some firms will benchmark other firms in the same industry. Such benchmarking, while not always an "apples-to-apples" comparison, provides at least some evidence to determine whether costs are in line with industry averages.

QUALITY CONTROLS

Quality controls describe the extent of variation in processes or products that is considered acceptable. For some companies, zero defects—no variation at all—is the standard. In other companies, statistically insignificant variation is allowable.

Quality controls influence the ultimate product or service outcome offered to customers. By maintaining consistent quality, customers can rely on a firm's product or service attributes, but this also creates an interesting dilemma. An overemphasis on consistency where variation is kept to the lowest levels may also reduce response to unique customer needs. This is not a problem when the product or service is relatively standardized such as a McDonald's hamburger, but

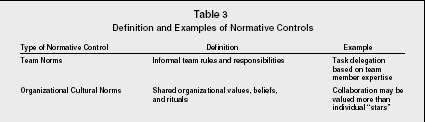

Definition and Examples of Normative Controls

| Type of Normative Control | Definition | Example |

| Team Norms | Informal team rules and responsibilities | Task delegation based on team member expertise |

| Organizational Cultural Norms | Shared organizational values, beliefs, and rituals | Collaboration may be valued more than individual "stars" |

may pose a problem when customers have nonstandard situations for which a one-size-fits-all solution is inappropriate. Wealth managers, for example, may create investment portfolios tailored to a single client, but the process used to implement that portfolio such as stock market transactions will be standardized. Thus, there is room within quality control for both creativity; e.g., wealth portfolio solutions, and standardization; e.g., stock market transactions.

NORMATIVE CONTROLS

Rather than relying on written policies and procedures as in regulative controls, normative controls govern employee and managerial behavior through generally accepted patterns of action. One way to think of normative controls is in terms how certain behaviors are appropriate and others are less appropriate. For instance, a tuxedo might be the appropriate attire for an American business awards ceremony, but totally out of place at a Scottish awards ceremony, where a formal kilt may be more in line with local customs. However, there would generally be no written policy regarding disciplinary action for failure to wear the appropriate attire, thus separating formal regulative controls for the more informal normative controls.

TEAM NORMS

Teams have become commonplace in many organizations. Team norms are the informal rules that make team members aware of their responsibilities to the team. Although the task of the team may be formally documented and communicated, the ways in which team members interact are typically developed over time as the team goes through phases of growth. Even team leadership be informally agreed upon; at times, an appointed leader may have less influence than an informal leader. If, for example, an informal leader has greater expertise than a formal team leader, team members may look to the informal leader for guidance requiring specific skills or knowledge. Team norms tend to develop gradually, but once formed, can be powerful influences over behavior.

ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE NORMS

In addition to team norms, norms based on organizational culture are another type of normative control. Organizational culture involves the shared values, beliefs, and rituals of a particular organization. The Internet search firm, Google, Inc. has a culture in which innovation is valued, beliefs are shared among employees that the work of the organization is important, and teamwork and collaboration are common. In contrast, the retirement specialty firm, VALIC, focuses on individual production for its sales agents, de-emphasizing teamwork and collaboration in favor of personal effort and rewards. Both of these example are equally effective in matching norms with organizational goals; the key is thus in properly aligning norms and goals.

The broad categories of regulative and normative controls are present in nearly all organizations, but the relative emphasis of each type of control varies. Within the regulative category are bureaucratic, financial, and quality controls. Within the normative category are team norms and organization cultural norms. Both categories of norms can be effective and one is not inherently superior to the other. The managerial challenge is to encourage norms that align employee behavior with organizational goals.

Scott B. Droege

FURTHER READING:

Barry, L.L. "The Collaborative Organization: Leadership Lessons from Mayo Clinic." Organizational Dynamics 33, no. 3 (2004): 228–242.

Lalich, J. "Watch Your Culture." Harvard Business Review 82, no. 1 (2004): 34–39.

Rollag, K., S. Parise, and R. Cross. "Getting New Hires Up to Speed Quickly". MIT Sloan Management Review 46, no. 2 (2005): 35–41.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: