EUROPEAN UNION

The European Union (EU) is an economic and political federation comprising 25 countries. The 15 original member nations are: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, the Republic of Ireland, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Ten new members as of May 2004 are: Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia. The EU represents the latest and most successful in a series of efforts to unify Europe, including many attempts to achieve unity through force of arms such as those seen in the campaigns of Napoleon Bonaparte and World War II.

In the wake of the Second World War, which devastated the European infrastructure and economies, efforts began to forge political union through increasing economic interdependence. In 1951 the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was formed to coordinate the production and trading of coal and steel within Europe. In 1957 the member states of the ECSC ratified two treaties creating the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom) for the collaborative development of commercial nuclear power, and the European Economic Community (EEC), an international trade body whose role was to gradually eliminate national tariffs and other barriers to international trade involving member countries. Initially the EEC, or, as it was more frequently referred to at the time, the Common Market, called for a twelve to fifteen year period for the institution of a common external tariff among its members, but the timetable was accelerated and a common tariff was instituted in 1967.

Despite this initial success, participation in the EEC was limited to Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. Immediately following the creation of the EEC a rival trade confederation known as the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) was created by Austria, Britain, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, and Switzerland. Although its goals were less comprehensive than those of the EEC, the existence of the EFTA delayed European economic and political unity.

By 1961 the United Kingdom indicated its willingness to join the Common Market if allowed to retain certain tariff structures which favored trade between Britain and its Commonwealth. Negotiations between the EEC and the United Kingdom began, but insurmountable differences arose and Britain was denied access to the Common Market in 1963. Following this setback, however, the Common Market countries worked to strengthen the ties between themselves, culminating in the merger of the ECSC, EEC, and Euratom to form the European Community (EC) in 1967. In the interim the importance of the Commonwealth to the British economy waned considerably and by 1973 Britain, Denmark, and the Republic of Ireland had joined the EC. Greece followed suit in 1981, followed by Portugal and Spain in 1986 and Austria, Finland, and Sweden in 1995.

Even as it expanded the EC worked to strengthen the economic integration of its membership, establishing a European Monetary System (EMS), featuring the European Currency Unit (ECU, later known as the Euro), in 1979 and passing the Single European Act, which strengthened the EC's ability to regulate the economic, social, and foreign policies of its members, in 1987. The EC took its largest step to date toward true economic integration among its members with the 1992 ratification of the Treaty of European Union, after which the EC changed its name to the European Union (EU). The Treaty of European Union also created a central banking system for EU members, established the mechanisms and timetable for the adoption of the Euro as the common currency among members, and further strengthened the EU's ability to influence the public and foreign policies of its members.

Although the EU has accomplished a great deal in its first four years of existence, many hurdles must still be crossed before true European economic unity can be achieved. Many EU nations experienced great difficulty in meeting the provisions required by the EU for joining the EMS, although eleven countries met them by the 1 January 1999 deadline. Meeting these provisions forced several EU members, including Italy and Spain, to adopt politically unpopular domestic economic policies. Others, such as the United Kingdom, chose not to take politically unpopular action and thus failed to qualify for participation. Even though the Euro was introduced according to schedule, economic unity has far outstripped political cooperation among EU members to date and real and potential political disagreements within the EU remain a threat to its further development.

STRUCTURE

The EU maintains four administrative bodies dealing with specific areas of economic and political activity.

COUNCIL OF MINISTERS.

The Council of Ministers comprises representatives, usually the foreign ministers, of member states. The presidency of the council rotates between the members on a semiannual basis. When issues of particular concern arise, members may send their heads of state to sit on the council. At such times the council is known as the European Council, and has final authority on all issues not specifically covered in the various treaties creating the EU and its predecessor organizations. The Council of Ministers also maintains the Committee of Permanent Representatives (COREPER), with permanent headquarters in Brussels, Belgium, to sit during the intervals between the council's meetings; and operates an extensive secretariat monitoring economic and political activities within the EU. The Council of Ministers and European Council decide matters involving relations between member states in areas including administration, agriculture and fisheries, internal market and industrial policy, research, energy, transportation, environmental protection, and economic and social affairs. Members of the Council of Ministers or European Council are expected to represent the particular interests of their home country before the EU as a whole.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION.

The European Commission serves as the executive organization of the EU. Currently each country has one commissioner except for the five largest countries that have two. The Commission enlarges as more countries join. The European Commission seeks to serve the interests of Europe as a whole in matters including external relations, economic affairs, finance, industrial affairs, and agricultural policies. The European Commission maintains twenty-three directorates general to oversee specific areas of administration and commerce within the EU. It also retains a large staff to translate all EU documents into each of the EU's twenty official languages. Representatives sitting on the European Commission are expected to remain impartial and view the interests of the EU as a whole rather than the particular interests of their home countries.

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT.

The European Parliament comprises representatives of the EU member nations who are selected by direct election in their home countries. Although it serves as a forum for the discussion of issues of interest to the individual member states and the EU as a whole, the European Parliament has no power to create or implement legislation. It does, however, have some control over the EU budget, and can pose questions for the consideration of either the Council of Ministers or the European Commission.

COURT OF JUSTICE.

The Court of Justice comprises thirteen judges and six advocates general appointed by EU member governments. Its function is to interpret EU laws and regulations, and its decisions are binding on the EU, its member governments, and firms and individuals in EU member states.

NOTABLE PROGRAMS

From its creation the EU has maintained the Economic and Social Committee (ESC), an appointed advisory body representing the interests of employers, labor, and consumers before the EU as a whole. Although many of the ESC's responsibilities are now duplicated by the European Parliament, the committee still serves as an advocacy forum for labor unions, industrial and commercial agricultural organizations, and other interest groups.

One ongoing area of contention among the members of the EU is agricultural policy. Each European nation has in place a series of incentives and subsidies designed to benefit its own farmers and ensure a domestically grown food supply. Often these policies are decidedly not beneficial to the EU as a whole, and lead to conflict between rival national organizations representing agricultural and fisheries industries. The degree of contention on agricultural and fisheries issues within the EU can be seen in the fact that nearly 70 percent of EU expenditures are made to address agricultural issues, even though agriculture employs less than 8 percent of the EU workforce. In an attempt to reduce conflict between national agricultural industries while still supporting European farmers, the EU adopted a Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) as part of the Treaty of European Union.

The CAP seeks to increase agricultural productivity, ensure livable wages for agricultural workers, stabilize agricultural markets, and assure availability of affordable produce throughout the EU. Although the CAP has reduced conflicts within the EU, it has also led to the overproduction of many commodities, including butter, wine, and sugar, and has led to disagreements involving the EU and agricultural exporting nations including the United States and Australia.

The European Social Fund (ESF) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) were established to facilitate the harmonization of social policies within EU member states. The ESF focuses on training and retraining workers to ensure their employability in a changing economic environment, while the ERDF concentrates on building economic infrastructure in the less-developed countries of the EU.

The European Investment Bank (EIB) receives capital contributions from the EU member states, and borrows from international capital markets to fund approved projects. EIB funding may be granted only to those projects of common interest to EU members that are designed to improve the overall international competitiveness of EU industries. EIB loans are also sometimes given to infrastructure development programs operating in less-developed areas of the EU.

LANGUAGES

The EU recognizes twently official languages: Danish, Dutch, English, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, and Swedish. Other languages spoken in Europe, such as Irish Gaelic, are considered "treaty languages" or "working languages," while dialects such as Catalan are considered "minority languages." Treaty or working languages are those into which the EU translates only its basic legal texts; it is up to each member state to translate whatever EU documents it deems important into minority languages. All EU documents are available in the twenty official languages.

RECENT EVENTS

The EU added ten new members on May 1, 2004: Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia. There are obstacles to inclusion of new members to the EU, however, in both the political and economic spheres. Any new members must conform to the national economic policy stipulations of the 1992 Treaty of European Union signed at Maastricht, and must also meet acceptable standards of internal political freedom. Turkey, for instance, was denied admission to the EU in 1997 due to its repression of its Kurdish minority, among other considerations. Similarly, Croatia was denied consideration for entrance due to its participation in ethnic cleansing activities during the Bosnian conflicts of the early to mid-1990s.

The major future event facing the EU since the adoption of the Treaty of European Union has been the adoption of the Euro as a single currency for members, which occurred in 2002.

THE EURO

The 1992 Maastricht Agreement established conditions that EU member nations would be expected to meet before they would be allowed to participate in the introduction of the single European currency. These conditions were designed to create a "convergence" among the various national economies of Europe to ease the transition to a single currency and ensure that no single country would benefit or be harmed unduly by its introduction. Such a convergence would also create greater uniformity among the various national economies of the EU, making administration of economic activity within the single-currency area more feasible. The conditions set for participation in the introduction of the Euro and inclusion in the single-currency area include:

- Maintaining international currency exchange rates within a specified range (called the Exchange Rate Mechanism or ERM) for at least two years prior to the introduction of the Euro.

- Maintaining long-term interest rates with 2 percent of the national inflation rate and within 1.5 percent of the three best-performing EU member states in terms of price stability.

- Maintaining public debt at no more than 3 percent of the gross domestic product.

- Maintaining total government debt at no more than 60 percent of gross domestic product.

These conditions have proven very difficult to meet for many EU members, and the United Kingdom was rejected for participation in the introduction of the Euro due to its failure to meet the provisions of the ERM in September 1992.

Despite these difficulties, implementation of the Euro has gone ahead on schedule through the three phases set forth at Maastricht. Phase one began in 1998 with an EU summit in Brussels, Belgium, that determined which of the fifteen member states had achieved sufficient convergence to participate in the introduction of the Euro. The selected participants were Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain (exceptions were Demark, Greece, Sweden and the UK). Phase two, which commenced on 1 January 1999, introduced the Euro as legal tender within the eleven selected countries, referred to as the single-currency area, although the new currency would only exist as a "currency of account," that is, it would exist only

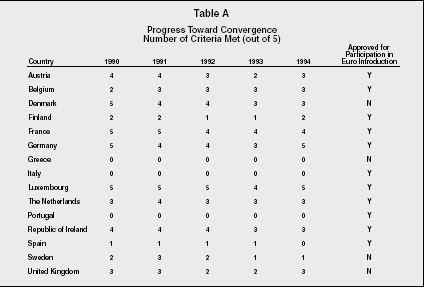

Progress TowardConvergence

Number of Criteria Met (out of 5)

| Country | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | Approved for Participation in Euro Introduction |

| Austria | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | Y |

| Belgium | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | Y |

| Denmark | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | N |

| Finland | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Y |

| France | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | Y |

| Germany | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | Y |

| Greece | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N |

| Italy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y |

| Luxembourg | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | Y |

| The Netherlands | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | Y |

| Portugal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y |

| Republic of Ireland | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | Y |

| Spain | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Y |

| Sweden | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | N |

| United Kingdom | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | N |

on paper or for electronic transactions, as no Euro notes or coins were yet in circulation. Instead, the existing currencies of the participating countries functioned as fixed denominations of the Euro. Phase two also included the subordination of the eleven national banks in the single-currency area to the European Central Bank. Phase three, which began on 1 January 2002 set the Euro banknotes and coins into circulation and by July 2002 it became the legal tender of the EMU countries replacing the national currencies. At the time of introduction there were twelve countries in the Euro area are: Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Greece. Demark, Sweden and the UK are not using the Euro.

The initial introduction of the Euro as a currency of account began with a resounding success, as the new currency rose immediately to an exchange rate of 1.17 U.S. dollars to the Euro. Uncertainties about the further progress of European Union raised by conflicts in the Balkans in 1999 soon dampened investor interest in the Euro, however, and its value fell to 1.04 U.S. dollars per Euro by the summer of that year. In fact there was a steady decline of the value of the Euro compared to the dollar. On January 1999 the value of the Euro was set at U.S. $1.18, but by mid-1999 it had dropped to $1.08 and by the end of the year it dropped to $1.01 and by mid 2000 it had fallen to $0.95.

Future implications of the adoption of a single currency within the twelve selected EU countries are a matter of speculation, but a few general observations can be made. Surveys conducted by the international accounting firm KPMG in the late 1990s reveal that major European corporations feel that the introduction of the Euro will cause prices to fall and wages to rise within the single-currency area, since corporations will no longer have to allow for fluctuations in currency exchange rates when establishing their prices.

Other implications of the adoption of a single currency are also foreseeable. International trade within the single currency area will be greatly facilitated by the establishment of what amounts to a single market, complete with uniform pricing and regulation, in place of twelve national markets. The creation of a single market will also spur increased competition and the development of more niche products, and ease the acquisition of corporate financing, particularly in what would formerly have been international trade among members of the single currency area. Finally, in the long term, the establishment of the single currency area should simplify European corporate structures, since in time nearly all regulatory statutes within the single currency area should become uniform.

THE UNITED KINGDOM AND THE EURO

Another question regarding the Euro's future involves the exclusion of the United Kingdom from the single-currency area. Although the U.K. continues to attempt to meet the Maastricht provisions, its entry

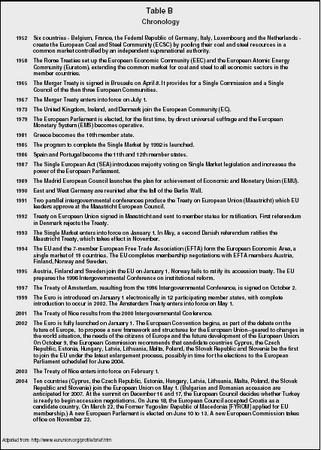

Chronology

| 1952 | Six countries - Belgium, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands - create the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) by pooling their coal and steel resources in a common market controlled by an independent supranational authority. |

| 1958 | The Rome Treaties set up the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom), extending the common market for coal and steel to all economic sectors in the member countries. |

| 1965 | The Merger Treaty is signed in Brussels on April 8. It provides for a Single Commission and a Single Council of the then three European Communities. |

| 1967 | The Merger Treaty enters into force on July 1. |

| 1973 | The United Kingdom, Ireland, and Denmark join the European Community (EC). |

| 1979 | The European Parliament is elected, for the first time, by direct universal suffrage and the European Monetary System (EMS) becomes operative. |

| 1981 | Greece becomes the 10th member state. |

| 1985 | The program to complete the Single Market by 1992 is launched. |

| 1986 | Spain and Portugal become the 11th and 12th member states. |

| 1987 | The Single European Act (SEA) introduces majority voting on Single Market legislation and increases the power of the European Parliament. |

| 1989 | The Madrid European Council launches the plan for achievement of Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). |

| 1990 | East and West Germany are reunited after the fall of the Berlin Wall. |

| 1991 | Two parallel intergovernmental conferences produce the Treaty on European Union (Maastricht) which EU leaders approve at the Maastricht European Council. |

| 1992 | Treaty on European Union signed in Maastricht and sent to member states for ratification. First referendum in Denmark rejects the Treaty. |

| 1993 | The Single Market enters into force on January 1. In May, a second Danish referendum ratifies the Maastricht Treaty, which takes effect in November. |

| 1994 | The EU and the 7-member European Free Trade Association (EFTA) form the European Economic Area, a single market of 19 countries. The EU completes membership negotiations with EFTA members Austria, Finland, Norway and Sweden. |

| 1995 | Austria, Finland and Sweden join the EU on January 1. Norway fails to ratify its accession treaty. The EU prepares the 1996 Intergovernmental Conference on institutional reform. |

| 1997 | The Treaty of Amsterdam, resulting from the 1996 Intergovernmental Conference, is signed on October 2. |

| 1999 | The Euro is introduced on January 1 electronically in 12 participating member states, with complete introduction to occur in 2002. The Amsterdam Treaty enters into force on May 1. |

| 2001 | The Treaty of Nice results from the 2000 Intergovernmental Conference. |

| 2002 | The Euro is fully launched on January 1. The European Convention begins, as part of the debate on the future of Europe, to propose a new framework and structures for the European Union--geared to changes in the world situation, the needs of the citizens of Europe and the future development of the European Union. On October 9, the European Commission recommends that candidate countries Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia be the first to join the EU under the latest enlargement process, possibly in time for the elections to the European Parliament scheduled for June 2004. |

| 2003 | The Treaty of Nice enters into force on February 1. |

| 2004 | Ten countries (Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia) join the European Union on May 1. (Bulgarian and Romanian accession are anticipated for 2007. At the summit on December 16 and 17, the European Council decides whether Turkey is ready to begin accession negotiations. On June 18, the European Council accepted Croatia as a candidate country. On March 22, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia [FYROM] applied for EU membership.) A new European Parliament is elected on June 10 to 13. A new European Commission takes office on November 22. |

into the single-currency area is unlikely in the near future. Having said this, British financial and insurance institutions, some of which are among the largest in the world, have already made provisions to trade in euros, as have many other financial institutions world-wide. Furthermore, the London and Frankfurt stock exchanges announced a planned alliance in 1998, to which the Spanish, Italian, and Dutch exchanges also

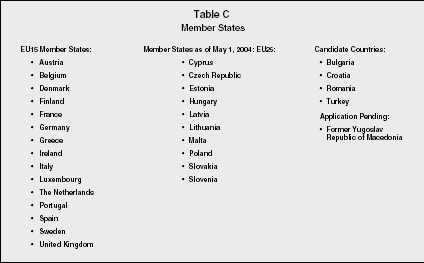

Member States

| EU15 Member States: | Member States as of May 1, 2004: EU25: | Candidate Countries: |

| •Austria | • Cyprus | • Bulgaria |

| •Belgium | • Czech Republic | • Croatia |

| •Denmark | • Estonia | • Romania |

| •Finland | • Hungary | • Turkey |

| •France | • Latvia | Application Pending: |

| •Germany | • Lithuania | • Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia |

| •Greece | • Malta | |

| •Ireland | • Poland | |

| •Italy | • Slovakia | |

| •Luxembourg | • Slovenia | |

| •The Netherlands | ||

| •Portugal | ||

| •Spain | ||

| •Sweden | ||

| •United Kingdom |

expressed an interest in joining. As such, it appears clear that the United Kingdom will eventually join the single-currency area.

OBSTACLES FACING THE EU

Although the single-currency area, also referred to as "Euroland," represents a formidable force in international trade, the EU faces several grave challenges as it strives to form an ever closer linkage of its national constituents.

Among the most intractable problems faced by Euroland is the fact that while economic interconnection has gone forward at a rather rapid pace through-out the history of the EU, political integration has progressed relatively slowly. For example, despite the fact that the Treaty of European Union created a central bank to supercede the national banks of its members, responsibility for the creation of fiscal policies remains in the hands of each national government. As such, there is great potential for the central authority and national economic policy making agencies to adopt conflicting programs. Furthermore, national political institutions within the EU are likely to be more responsive to the desires of their national constituencies than to the well being of Euroland as a whole, especially in times of economic instability. It is difficult to see how voters in the nations of the EU will be able to put the good of Euroland ahead of their own particular interests, but it must also be said that the EU has surmounted similar obstacles in its history to date.

A second problem also arises out of the composition of Euroland. According to the optimal currency theory first posed by American Robert Mundell in 1961, in order for a single currency to succeed in a multinational area several conditions must be met. There should be no barriers to the movement of labor forces across national, cultural, or linguistic borders within the single-currency area; wage stability throughout the single currency area; and an area-wide system to stabilize imbalanced transfers of labor, goods, or capital within the single-currency area. These conditions do not exist in present-day Europe, where labor mobility is small and wages vary widely among EU member countries.

Furthermore, the present administrative structure of the EU is not powerful enough to redress imbalanced transfers, which are bound to occur periodically. Such imbalances would engage the sort of political response discussed previously, to the detriment of the EU as a whole.

Optimal currency theory also holds that for a single currency area to be viable it must not be prone to asymmetric shocks, that is, economic events that lead to imbalanced transfers. Ideally, a single-currency area should comprise similar economies that are likely to be on similar cycles, thus minimizing imbalances. Similarly, the need for a freely transferable labor force within the single-currency area is also necessary to minimize imbalances, since each national member of the area must be able to respond flexibly to changes in wage and price structures.

The EU has made remarkable progress during its first forty-seven years. Although the further strengthening of the EU, especially in political matters, faces major obstacles, the continued enhancement of economic ties binding members is likely to increase the political unity of EU members over time. That this is feasible is evidenced by the efforts of EU nations to conform to the stipulations of the Maastricht Agreement. Maintaining stable currency exchange rates, reducing public and overall government debt, and controlling long-term interest rates are all areas in which national governments and fiscal agencies had exercised complete autonomy in the past. Before the implementation of the Euro's second phase, many doubted that the EU member states could put aside their own internal interests to meet the Maastricht provisions; however, eleven of the fifteen managed to do so. Significantly, many had to experience economic slowdowns and increased unemployment in order to do so. Such resolve bodes well for continued strengthening of European unification in both political and economic areas. In fact, the history of the EU to date has been one of overcoming obstacles similar to those faced during the first two phases of the introduction of the Euro, and a unified Europe is and will remain a fact of international economic life for the foreseeable future.

SEE ALSO: Free Trade Agreements and Trading Blocs ; International Business ; International Management

Grant J. Eldridge

Revised by Judith M. Nixon

FURTHER READING:

Alesian, A., and R. Rerotti. "The European Union: A Politically Incorrect View." Journal of Economic Perspectives 18, no. 4 (2004): 27–48.

"Europe Ten Years from Now." International Economy 18, no. 3 (2004): 34–39.

"European Union in the U.S." Available from < http://www.eurunion.org >

McCormick, J. Understanding the European Union: A Concise Introduction. 2nd ed. New York: Palgrave, 2002.

Phinnemore, D., and L. McGowan. A Dictionary of the European Union. London and Chicago: Europa, 2002.

Pinder, J. The European Union: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Reid, T.R. The United States of Europe: The New Superpower and the End of American Supremacy. New York: Penguin Press, 2004.

Vanthoor, W.F.V. A Chronological History of the European Union, 1946–2001. 2nd ed. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar, 2002.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: